|

September 2007, Volume 29, No. 9

|

Original Articles

|

General practitioners with a higher qualification in Family Medicine or General Practice: are they better in diagnosing and treating patients with depression and anxiety?Samuel Y S Wong 黃仰山, Karen Lee 李嘉汶,Kenneth Chan 陳敬堯,Albert Lee 李大拔 HK Pract 2007;29:348-356 Summary

Objective: To compare the general practitioners with higher qualifications

in Family Medicine or General Practice with those without in how they diagnose and

treat patients presenting with depression and anxiety in primary care.

Keywords: Family Physicians, Training, Higher Qualification, Depression, Anxiety 摘要

目的: 比較家庭醫生持有較高學歷與否對在診治抑鬱症和焦慮症患者時的異同。

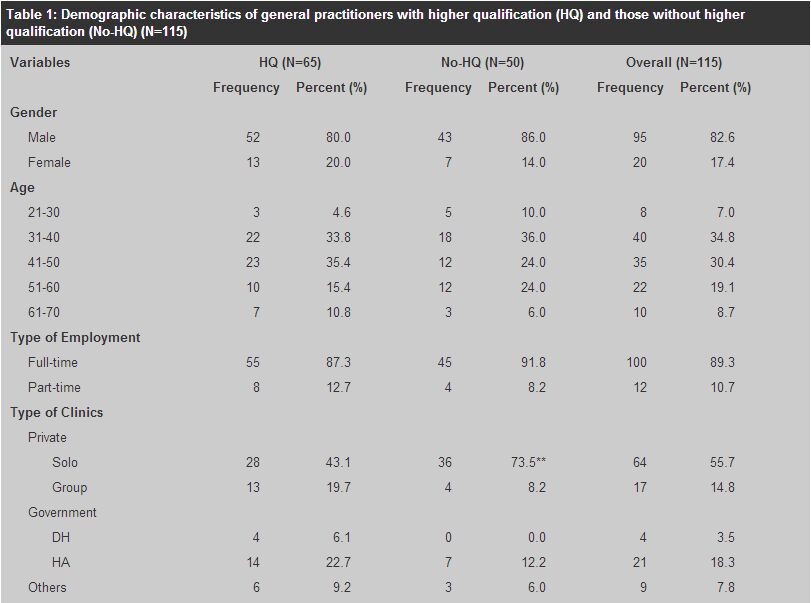

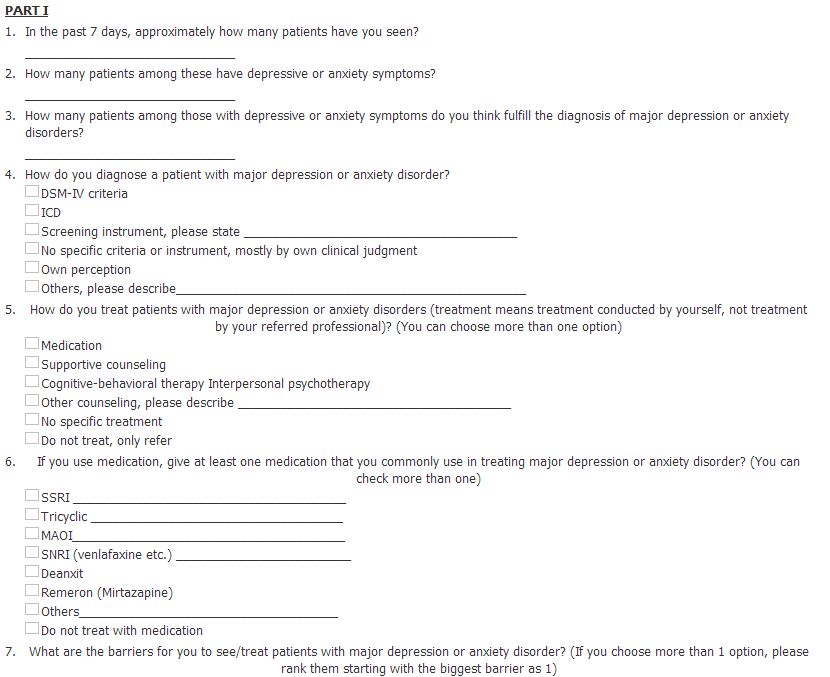

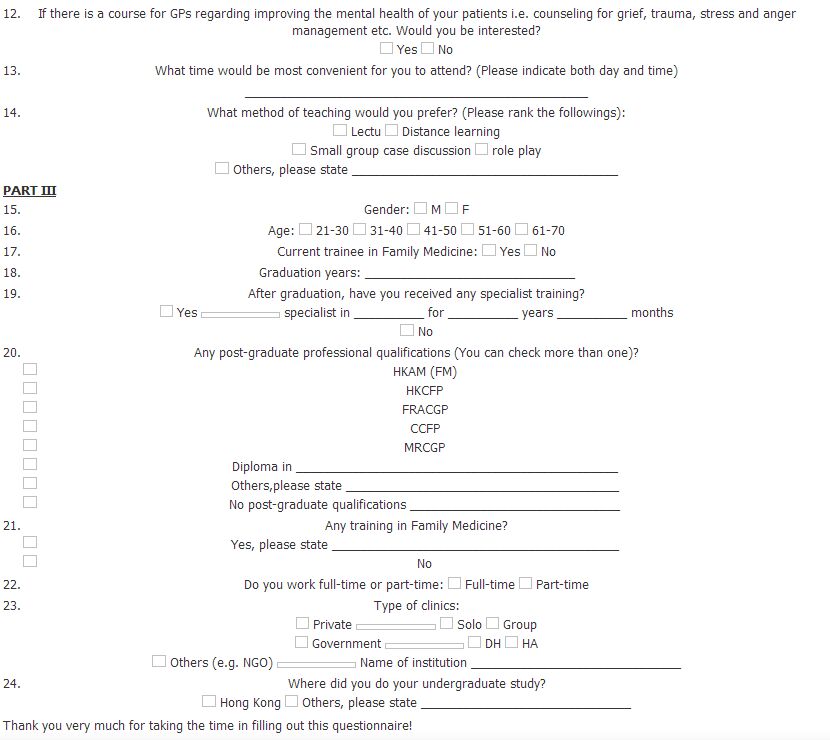

主要詞彙: 家庭醫生、訓練、較高學歷、抑鬱症、焦慮症。 Introduction Most patients with emotional distress receive psychological care in the primary care setting.1 Although depression and anxiety are two of the most common illnesses found in general practice, they are often under-diagnosed and under-treated.2,3 Research in the West showed that less than 50% of depressive episodes were identified in primary care.4-6 There are several factors that can contribute to the under-diagnosis and under-treatment of anxiety and depression in primary care. Physicians' attitudes and skills,7,8 time constraints,9 low reimbursement10 and physician's self-perceived competence and formal training could all contribute to this problem.11-13 The first and last factors are related to residency training in the specialty which, in principle, should have an impact on how the physicians diagnose and manage patients with depression and anxiety. This is especially an important area to explore as most training programmes in Family Medicine around the world put large emphasis on training their residents in taking a bio-psychosocial approach to managing patients in primary care. Although most programmes emphasize the importance of adopting a bio-psychosocial approach in the care of patients in Family Medicine and General Practice, few studies have been conducted to evaluate the impact of these programmes or the obtaining of higher qualifications in Family Medicine or General Practice on physicians' diagnosis and management of patients presenting with psychological problems. Hong Kong is a good place to explore this area owing to its unique composition of general practitioners. In Hong Kong, anyone who completed 5 years of medical school undergraduate studies with one year of internship can become a general practitioner. Residency training in Family Medicine or General Practice is not mandatory for physicians to engage in general practice. At the same time, there are general practitioners who completed residency training in Family Medicine or General Practice (possess higher qualifications in Family Medicine or General Practice) either in Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and the United States. In this study, a survey was carried out among all Family Medicine tutors affiliated with a university in Hong Kong. The impact of having a higher qualification in Family Medicine or General Practice on diagnosis and management of depression and anxiety was explored by comparing the strategies for diagnosis and management of depression and anxiety between general practitioners who have higher qualifications in Family Medicine or General Practice against those without. Methods A postal questionnaire was sent to all Family Medicine tutors affiliated with the Chinese University of Hong Kong. These tutors have been involved in clinical teaching (clinical attachments) for undergraduate medical students during the last three years. The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first part asked about their patient characteristics, their own strategies in diagnosing and treating patients with depression and anxiety disorders and their perceived barriers and referral route when caring for patients with depression and anxiety disorder. The second part inquired about their confidence in treating patients with major depression or anxiety disorders by the use of a 1 to 10 visual analogue scale. Sources of knowledge in treating depression and anxiety disorders in primary care (Formal courses or CME courses on psychological medicine included) and their interests in participating in future Continued Medical Education courses on improving mental health of their patients were also inquired. Demographic information including gender, age, training status, year of graduation, prior residency/vocational training in Family Medicine with post-graduate qualifications and types of practice (private vs. public; solo vs. group) were collected. A second and third mailing was sent to all tutors again after 4 and 6 weeks. All these mailings included a covering letter which stated the purpose of the study with a lucky draw of 500 dollar coupon as the incentive. All questionnaires were returned anonymously. The study was approved by the local Behavioural and Survey Ethics Committee and only results from demographics, diagnostic and management strategies were reported here. Higher qualification in Family Medicine or General Practice was defined by those physicians with post-graduate qualifications in Family Medicine or General Practice including Fellow of Hong Kong Academy of Medicine (Family Medicine) (FHKAM[FM]), Fellow of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (FHKCFP), Fellow of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (FRACGP), Certificant of The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CCFP), and Member/Fellow of the Royal College of General Practitioners (M/FRCGP). Other diplomas were not considered as a higher qualification in the current study. Years of experience was defined as the number of years after graduation from medical school. "No treatment" referred to "no specific treatment" or "do not treat, only refer" on the questionnaire. Data were analyzed using the Statisical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). For primary analyses, differences in diagnostic and management strategies in caring for patients with depression and anxiety and demographic variables were compared between physicians with and without higher qualifications by the use of Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. A two-sided p-value of 0.05 or less was considered as statistically significant. For secondary analyses, adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for using the various strategies of diagnosis and types of treatment for diagnosing and management patients presented with depression and anxiety disorders in relation to having a higher qualification in Family Medicine or General Practice were calculated by using binary logistic regression. Adjustments were made for potential confounders including age, gender, years of experience and types of clinics (private solo, private group and government). The study was approved by The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong - New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee. Results Subject characteristics After the three mailings, a total of 115 questionnaires were received with a response rate of 64.2%. The overall demographics, and separate demographic information between general practitioners with and without higher qualifications were shown in Table 1. Overall, 82.6% of tutors were male, with most in the age range of 31-50 (65.2%). 89.3% engaged in full time practice and more than half were in solo practice (55.7%). According to our definition of a higher qualification, there were 65 practitioners holding at least one of the following: FHKAM(FM), FHKCFP, FRACGP, CCFP and/or M or FRCGP. The majority of practitioners completed their undergraduate study in Hong Kong, with 43% of the general practitioners with more than 20 years of practice after graduation. These characteristics of general practitioners were similar to previous studies conducted among general practitioners in Hong Kong.14

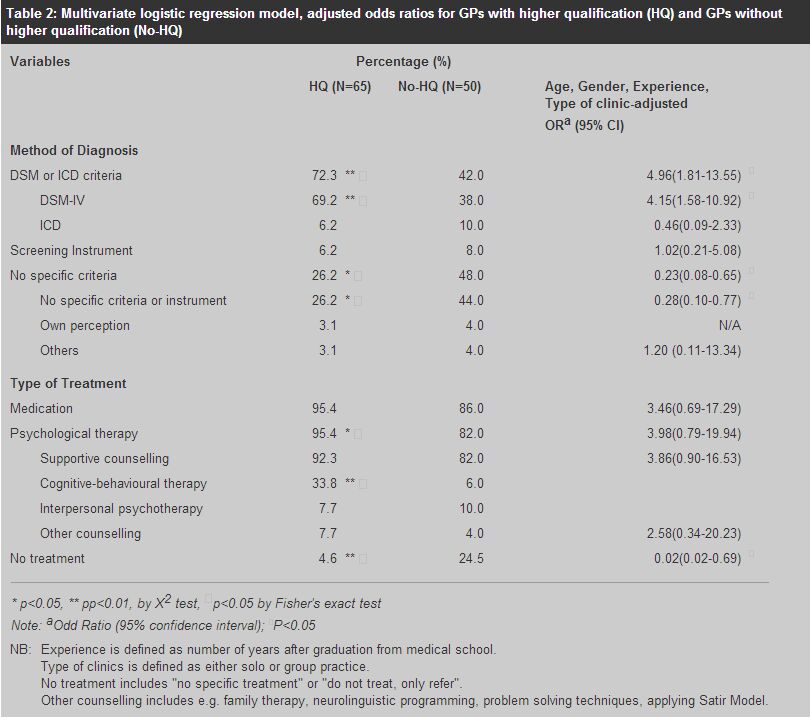

There were no statistically significant differences in demographic characteristics between those with and without higher qualifications by chi-square test (Table 1) except "type of clinics". There was a higher proportion of physicians without higher qualifications who were in private solo practice when compared with those with higher qualifications (73.5% vs. 43.1%, p<0.01). Diagnostic and management strategies of general practitioners with and without higher training General practitioners with higher qualifications were more likely to use DSM or ICD criteria in the diagnosis of depression and anxiety (72.3% vs. 42.0%, p<0.01 by chi-square tests). Moreover, they were less likely to use strategies such as "no specific criteria" that included "no specific criteria or instrument", "own perception" in diagnosing patients with major depression or anxiety disorders (26.2% vs. 48.0%, p<0.05 by chi-square tests). For management of patients with depression and anxiety disorders, physicians with higher qualifications were more likely to use psychological treatment (supportive counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy or other counselling) (95.4% vs. 82.0%, p<0.05 by chi-square tests) in treating patients with depression and anxiety disorders. They were less likely to use "no treatment (no specific treatment or do not treat, just refer)" (4.6% vs. 24.0%, p<0.01 by chi-square tests) in managing patients with depression and anxiety disorders. Similar results were obtained when the association between diagnostic/management strategies and higher qualifications were studied using binary logistic regression. Having higher qualifications is associated with increased adjusted odds of using DSM or ICD criteria in diagnosing depression or anxiety after adjustments were made for gender, age, types of clinics and years of experience (defined as number of years in practice after undergraduate graduation) (Odds Ratio=4.96; Confidence Intervals from 1.81 to 13.55, p <0.05). Those with higher qualifications were also less likely to use no specific criteria in diagnosing patients with depression or anxiety disorders [Adjusted odds ratio (OR) =0.23; Confidence Interval = 0.08 to 0.65]. For management of patients with depression and anxiety disorders, those with higher qualifications were more likely to use psychological treatment especially cognitive behavioural therapy when compared to those without higher qualifications [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 9.24; Confidence Interval = 2.20 to 38.80]. (Table 2)

Discussion Few studies have explored differences in diagnosing and treating patients with depression and anxiety among general practitioners with and without higher qualifications in Family Medicine or General Practice. As post-internship training in a chosen specialty or General Practice/Family Medicine is mandatory in most Western countries before a physician could practice medicine, the unique situation in Hong Kong makes it ideal to study this research area. Findings from the current study showed that general practitioners with higher qualifications were more likely to use standardized and well established diagnostic criteria in making diagnosis for depression and anxiety. Moreover, they are more likely to use psychological therapy compared to physicians without higher qualifications. Previous studies showed that those with specialized training in Family Medicine or post-graduate psychiatric training were more likely to treat patients with depression by themselves rather than refer to other health professionals.14 Moreover, they performed better in detecting mental disorders.15 Results from our study are consistent with these findings which showed that these physicians who had higher qualifications used more standardized criteria in diagnosing depression and anxiety, more often treated these disorders themselves rather than referring to others initially. Previous studies showed that preferences in the management of psychological disorders such as depression in primary care settings are influenced by a variety of factors. One factor is whether the primary care physicians have had prior experience with a treatment strategy. Indeed, prior experience is more important than physician's socio-demographics as a predictor variable in predicting treatment strategies in the care of patients with depression.16 As a result, prior experience in psychiatric rotation during the Family Medicine residency training could have made these physicians more likely to use more appropriate diagnostic criteria and management. Other factors that influence general practitioners' management of psychosocial problems include their motivation, interest in psychiatry,17 positive attitudes to psychosocial problems,18 and prior participation in CME.15,16 There are a few limitations in this study. First of all, general practitioners who have higher qualifications could be a group who are more motivated and thus have more interest in Family Medicine in general. As a result, physician characteristics such as motivation and their interest in psychiatry may be confounders16,17 in the relationship between training and diagnostic and management strategies. Moreover, they may be a group who are more likely to take CME courses for diagnosing psychological diseases in primary care which are offered by several organizations including the two universities in Hong Kong. Knowledge obtained from these CME courses could affect how these physicians diagnose and manage depression and anxiety. However, an analysis of the data on "source of knowledge" showed that there were no differences in the amount of CME courses in psychological medicine taken by general practitioners with and without higher qualifications. This showed that the differences observed could not be explained solely by physician's motivation or enrolment in CME courses alone. Another limitation is that this survey was conducted among Family Medicine tutors who are affiliated with the Chinese University of Hong Kong. As a result, these general practitioners may be more motivated and more up to date on how to care for patients in primary care.16 However, as we were able to show differences in their behaviour in the care of patients with depression and anxiety even within this group, it indicates that the impact of having a higher qualification on the practitioners' behaviour is large. Finally, the results from this study were based on physicians' self reports, and not on observed behaviour. As a result, self report bias could not be prevented. Conclusion We conclude that physicians with higher qualifications in Family Medicine or General Practice used more standardized criteria in diagnosing depression and anxiety. Moreover, they are more confident and tend to use more treatment strategies to manage patients with these disorders rather than referring to other health care professionals. As depression and anxiety disorders are very common in the primary care settings and constitute a large proportion of medical service utilization, having more general practitioners with vocational training will facilitate effective diagnosis and management of these common disorders. This can lead to substantial cost offsets in our health care expenditure by reducing inappropriate use of other medical and surgical care by these patients.18 Acknowledgements Grant support was provided by Direct Grant 03/04 of the Faculty of Medicine at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. The authors thank the 33 physicians who took time from their busy practices to participate in the study.

Key messages

Samuel Y S Wong, MD, FRACGP

Assistant Professor, Karen Lee, MA(Psy) Research Assistant, Kenneth Chan, BSocSc Research Assistant, Albert Lee, MD, MPH, FRCGP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Professor & Head, Elderly Health Service, Department of Health. Correspondence to : Professor Samuel Y S Wong, Department of Community and Family Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong.

References

|

|