|

December 2009, Volume 31, No. 4

|

Discussion Papers

|

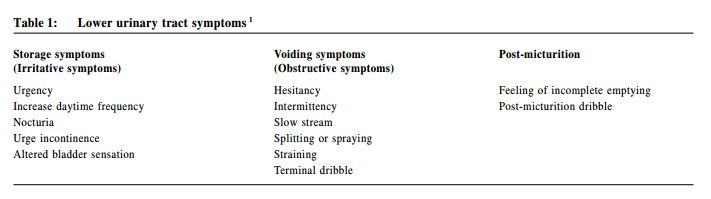

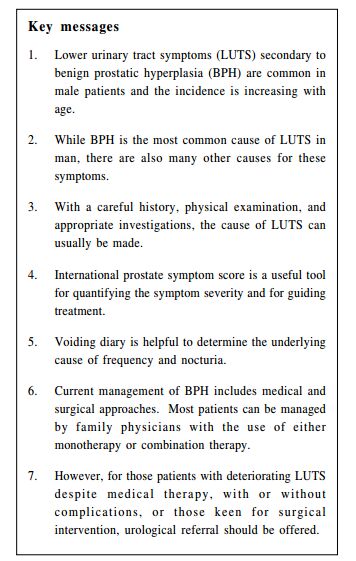

Primary care physicians' attitudes towards patients with mental health problems in Hong KongTP Lam 林大邦, YS Ku 辜彥璇 HK Pract 2009;31:186-189 Summary Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) are common among middle aged to elderly male patients. The main challenge in the management is to make the correct diagnosis and exclude other possible differential diagnoses that can also cause LUTS. A systemic approach in history taking and physical examination will help to identify most of the underlying causes of LUTS and this can be further confirmed by appropr iate investigations. After establishing the diagnosis of BPH, subsequent management depends on the severity of symptoms, their effect on patients’daily activities, and also the presence of complications. The majority of patients can be managed with behavioural modification and medications prescribed by family physicians. However, for patients with progressive disease and complications, urological refer ral may be necessary for possible surgical intervention. 摘要 由良性前列腺增生(BPH)引起的下尿路症狀(LUTS)是中 老年男性患者的常見問題。在處理上的主要挑戰是作出正確 診斷和排除與下尿路症狀相似的其他鑒別診斷。有系統地問 診和體檢將有助確定下尿路症狀的病因,適當的醫學檢查可 進一步確診。 在診斷為良性前列腺增生後,其處理方法將取決於症狀 的嚴重性,對患者日常生活的影響,及是否有併發症。大多 數患者可以通過行為改變和由家庭醫生處方藥物進行治療。 但當病情逐漸惡化及出現併發症時,則可能要被轉介泌尿 科,以確定外科治療的需要。 Introduction Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are among the commonest urological complaints in male patients (Table 1). Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is probably the commonest cause for these symptoms especially in the elderly population.1 A survey conducted by the Hong Kong Urological Association found that 42% of patients over 60 years old had significant lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and estimated that 160,000 men could be moderately or severely affected in Hong Kong. As the majority of patients with BPH can be managed with lifestyle modification and medical treatment, family physicians could be one of the main health care providers for these patients. However, besides BPH, there is also a long list of differential diagnoses that can result in LUTS (Table 2). Therefore, a correct diagnosis with appropriate investigations, treatment and proper referral is a challenge to family physicians. In this review, the basic approach to males presenting with LUTS will be discussed, followed by an overview of the latest management for BPH.

Evaluation According to the recommended clinical practice guidelines from different urological associations on the management of BPH, initial evaluation of all patients presenting with LUTS suggestive of BPH should include a medical history, symptoms assessment using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), physical examination with digital rectal examination, focused neurological examination, and urinalysis. BPH is basically a clinical diagnosis; there is no simple confirmatory blood test or investigation. As in many patients with BPH, serious medical conditions may coexist that result in LUTS. Therefore, the attending physician should be aware of points of suspicion during history and physical examination, and arrange appropriate work-up for their patients (Table 3).

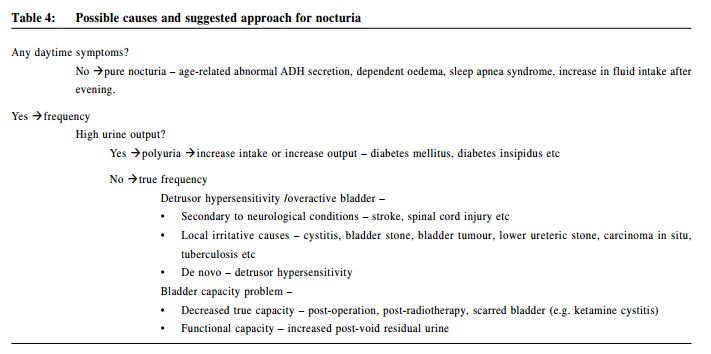

The age of presentation is important. Although the pathological changes of BPH start to appear by 30 years of age, it takes a long time for it to grow to a significant size so as to cause clinical symptoms.1 Therefore, patients with BPH usually present after the age of 50 years. At the other end, patients presenting after the age of 80 years may have an age-related hypocontractile bladder that worsen the symptoms. Irritative symptoms, especially nocturia, are common presenting symptoms and they tend to affect the quality of life of patients more significantly. Further enquiry on the nature of the symptoms is important. Nocturia is defined as two or more night time voids, and it should be differentiated from those voiding due to insomnia. The presence of daytime symptoms and other lower urinary tract symptoms help to differentiate genuine nocturia from polyuria and frequency (Table 4). Patients with BPH typically have a gradual onset of both voiding and storage symptoms. For patients with predominant irritative symptoms, other differential diagnoses should be considered, especially if the symptoms developed within a short time. Inflammatory causes, such as urinary tract infection, prostatitis, and lower ureteric stone should then be excluded. The presence of haematuria, together with irritative symptoms should be investigated for possible malignancy until proven otherwise. One of the late signs for voiding problems is nocturnal enuresis, which means unnoticed urine leak at night. This usually signifies overflow incontinence, and can be due to chronic bladder outlet obstruction, such as BPH or stricture, or a hypocontractile bladder. Bladder scan may be needed to document the residual urine and urgent referral for urologist opinion is warranted in these patients.

The presence of any significant past or current medical or surgical conditions should be noted. Past history of urological conditions such as urethral reconstruction, bladder surgery, and prostatic surgery would increase the risk of subsequent urethral stricture or change in bladder capacity. Other pelvic surgery, such as anterior resection of the rectum, may also cause damage to the pelvic nerve plexus, resulting in a hypocontractile bladder. Previous spinal trauma or surgery may cause damage to the nervous system, leading to a neurogenic bladder. In fact, patients with a historyof prolonged hospitalization with urethral catheterization and subsequent development of LUTS should raise the suspicion of urethral stricture secondary to instrumentation. There are many medical conditions that can also cause LUTS. Any significant neurological conditions, such as Parkinsonism and cerebrovascular accidents, can affect the urinary tract in different ways and referral to a urologist for urodynamic assessment may be necessary in some cases. A long history of diabetes may result in autonomic neuropathy that affects bladder contractility. Diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus are common causes of polyuria and polydipsia. Nevertheless, inappropriate usage or timing of diuretics may also result in frequency or nocturia. Some patients may have only nocturia and no daytime symptoms. The commonest cause may be just excessive fluid intake during the evening. Other pathological causes for nocturia may include obstructive sleep apnoea, dependent oedema and change in the diurnal pattern of anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) secretion in elderly.3, 4 Physical examination should focus on the identification of conditions that can affect voiding and potential complications of BPH. Abnormal gait and limited walking ability may suggest significant underlying neurological pathology. The return of interstitial fluid into the vascular space after resuming a recumbent position in those with ankle oedema is a known cause of nocturia. A distended bladder may suggest chronic retention of urine. Phimosis can be one of the rare causes for difficulty in voiding. While the patient is prepared at the lateral position for digital rectal examination (DRE), an inspection of the back may identify scars due to previous spinal trauma or operation and signs of spina bifida occulta, which may all result in a neurogenic bladder. During DRE, the anal tone and prostate size should be assessed. Most patients with BPH have clinically enlarged prostates. Therefore, for patients with relatively small prostate, less than 30gm, other possible causes of LUTS should be considered before labeling them as suffering from BPH. In a patient of appropriate presenting age with a gradual onset of LUTS, both irritative and obstructive with no suspicious past medical history, and an enlarged prostate on examination, the diagnosis of BPH can be made clinically. Some basic work up, such as renal function test and urine culture, can be done before commencing treatment. However, for those patients with a suspicious history or physical examination, other investigations may be necessary (Table 5). For patients suspected to have problems such as neurogenic bladder or urethral stricture, urological referral may be needed for a more detailed assessment.

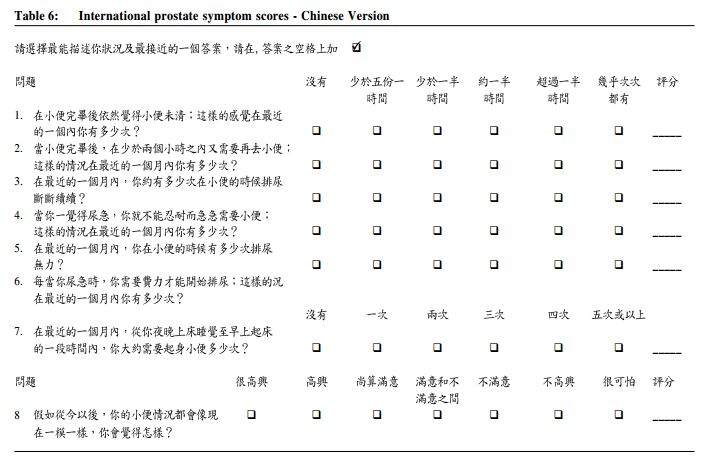

Uroflowmetry and post-voiding bladder scan for residual urine volume are a pair of important tools for urologists to quantify obstructive symptoms. A well performed uroflowmetry should have a minimal voided volume of more than 150 cc. A void less than 150 cc may not be able to represent the actual voiding condition of the patient. Normal flow rate should have a maximum flow rate of more than 15 cc/second with a bell-shaped curve, with minimal residual urine. BPH patients will usually have a lower flow rate, i.e. less than 15 cc/second, and increased residual urine. The lower the peak flow rate and larger the residual volume, the more severe the obstruction from the BPH. These information will be important to guide our treatment, as well as for monitoring the progress of the patient. While uroflowmetry may not be necessary for every BPH patient, IPSS can be helpful to quantify symptom severity and guide our management (Table 6).4 Basically, it is a two-part self-administrated questionnaire to assess the patient's voiding condition in the past four weeks. The first part is a symptom score assessment, containing seven questions with a total mark at the end. This is based on the initial American Urological Association symptom score (AUA-7),5 which contained seven questions asking seven most representative LUTS that occurred in BPH patients. Each question has a score from 0 to 5, related to the frequency of the occurrence of the symptoms. The total score will be from 0 to 35. The total score will help to quantify patient's symptoms and also stratify them into mild, moderate or severe, if the total score is 0-7, 8-19 and 20-35 respectively. The second part is an additional quality of life question that assesses the impact of the symptoms on patients. These eight questions were then named IPSS. The combination of the two parts provides doctors with an idea about symptom severity in an objective manner and the impact of these symptoms on the patient's daily life, serving to guide treatment and for progress monitoring.

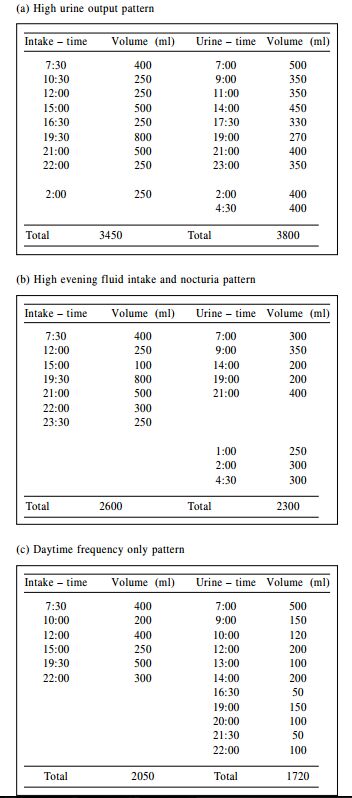

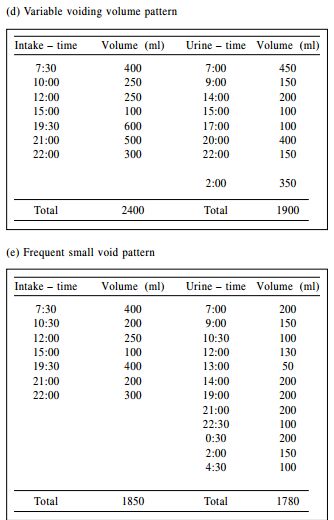

A simple and useful investigation tool for LUTS assessment is the voiding diary. It is a 24-hour selfreporting drinking and voiding record. We usually advise the patient to get a clean measuring jar and measure the volume of his glass and bowl. The recording starts in the morning. The patient is instructed to pass every void into the jar and document the time and volume. Meanwhile, he should try to record the time and volume of fluid he drinks (including soup and congee) as accurately as possible. This recording should be repeated for a few times to improve the accuracy. Common patterns that can be obtained include (Figure 1):

a. High total urine output with high fluid intake - the high fluid intake could

be due to either pathological or psychogenic polydipsia. Advice on reducing fluid

intake or treating underlying causes of polydipsia will improve the condition (Figure

1a).

Serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurement is optional, but should be offered:

(1) to patients with at least a 10-year life expectancy and for whom knowledge of

the presence of prostate cancer would alter management, or

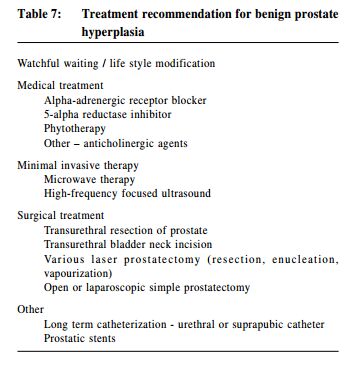

Management of benign prostate hyperplasia For patients with BPH, if they have only mild LUTS (IPSS 0-7) that are not bothersome, watchful waiting with behavioural modifications such as modification of oral fluid intake, avoiding caffeine/tea/alcohol or changing the timing of concomitant medication (e.g. diuretic) can provide considerable relief. For patients with moderate to severe symptoms (IPSS 8-35), medical therapy can be recommended if they preferred non-invasive therapy. However, for patients with significant symptoms despite medical treatment or complications secondary to BPH, surgical treatment may be indicated (Table 7).

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers (ARB) target the 'dynamic' component of BPH and offer quick relief of symptoms. The underlying mechanism is to inhibit activation of alpha-1 adrenergic receptors, resulting in the relaxation of prostatic and bladder neck smooth muscle, thereby decreases LUTS. The side effects of latest selective alpha blockers are much less than that of the earlier generation.6, 7 However, they do not reduce prostatic size. The American Urological Association (AUA) recommendation suggested that alfuzosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin and terazosin are appropriate treatment options for patients with LUTS secondary to BPH and they have equal clinical effectiveness.8 However, earlier generations of alpha blockers, such as phenoxybenzamine and prazosin, are currently not recommended.9 5-alpha reductase inhibitors This hormonal therapy blocks the conversion of testosterone to active dihydrotestosterone within prostatic cells and is more likely to work in men with large prostates. Finasteride has been shown to reduce prostatic size, increase peak urinary flow rate, and reduce BPH symptoms. However, notable adverse effects including impotence (5-9%) and ejaculation disorder are relatively common. AUA recommendation suggests that 5-alpha reductase inhibitors such as Finasteride and Dutasteride are appropriate and effective treatments for patients with LUTS associated with demonstrable prostatic enlargement only.8 With the publication of the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptom (MTOPS) research group, 10 physicians and patients are becoming more aware of the ARB and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors combination (combination therapy). Currently, the use of combination therapy is mainly indicated in symptomatic patients with enlarged prostates (> 30cc).8, 11 Surgery and other therapies Surgery and other therapies According to AUA guidelines, the choices of surgical approach (open versus endoscopic) and energy source (electrocautery versus laser) are technical decisions based on the patient's prostate size, individual surgeon's judgment and experience, and the patient's comorbidities.6 Candidates for surgical intervention include those with

1. Bothersome symptoms While transurethral resection (TUR) of the prostate is still regarded as the gold standard in the management of BPH, new treatments with less complications are emerging. The use of various lasers for resection/ enucleation/vaporization are currently the commonest alternative surgical treatment for BPH. Holmium laser and KTP-laser are the main types of laser used, and both provide excellent haemostatic results.12 Holmium laser is frequently used in a "cutting" manner to enucleate the obstructing BPH (HoLEP). KTP-laser ("Green laser") is used to vaporize prostate tissues. Both lasers can produce an immediate channel after surgery, similar to TUR prostate. Moreover, there is no need for patients to stop anti-platelet agents or anticoagulation during laser therapy. Both lasers can work under normal saline and thus avoid the risk of TUR syndrome. Besides the use of laser, the development of bipolar technology in endoscopic resection is also becoming more mature and popular. Bipolar resection, as compared to traditional monopolar resection, has also the advantage of avoiding glycine for irrigation, and hence minimizes the risk of TUR syndrome. For patient with huge prostates (> 100 cc), laparoscopic retropubic enucleation of prostate is an alternative for traditional open surgery and can provide excellent results. For patients with high surgical risks, prostatic stents, e.g. Memocath, are good alternatives to long-term urethral or suprapubic catheters. Stent placement can be performed under local anaethesia through flexible cystoscopy. For the detailed complications of various procedures, please refer to the excellent review by Keister and Neal.5 When to refer For LUTS, if there is any clinical suspicion of a neurogenic bladder, urethral stricture, or other surgical conditions (including stones, tumours, etc), urological referral is necessary for further assessment and management. Patients with gross haematuria should also be referred for further workup to exclude bladder pathology. BPH is a progressive disease though the progression is different in individual patients. Simple cases can be managed by family physicians. Referral to urologists is indicated if

Conclusion BPH is a common condition in male patients. The diagnosis can easily be obtained after a careful clinical evaluation. The assessment of symptom severity will help to guide treatment. Most patients can be managed by medical and behavioural approaches. However, for patients with symptoms that are not relieved by medication or with complications secondary to BPH, urological referral for further evaluation and consideration for surgery will be needed.

Chi-Fai Ng, MBChB, FRCS (Edin), FRCS Ed (Urol), FHKAM (Surg)

Associate Professor Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong See-ming Hou, MBBS (HK), FRCS (Edin), FHKAM (Surg) Consultant Division of Urology, Prince of Wales Hospital Correspondence to : Professor Chi-fai Ng, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, NT, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|