|

December 2009, Volume 31, No. 4

|

Original Articles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Is the number of clinical problems per consultation correlated with poorer ICPC coding practices in primary care clinics? A pilot study in two distinct clinic settingsHung-yung Wong王孔勇, Edwin YH Chan陳彥衡, Martin CS Wong黃至生, Liang Jun梁峻 HK Pract 2009;31:158-165 Summary

Objective: examine the association between multiple medical problems

and the accuracy and completeness of International Classification of Primary Care

coding (ICPC-2) in Family Medicine Specialist Clinics (FMSCs) and General Out Patient

Clinics (GOPC).

Keywords: ICPC coding, accuracy, completeness, associated factors 摘要

目的:研究家庭醫學專家診所(FMSC)和普通門診 (GOPC),多重疾病與基層醫療國際分類編碼(ICPC-2)之準確性和完整性之間的聯。

主要詞彙:ICPC編碼,準確性,完整性,相關因素。 Introduction Published by the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) in 1998, the revised International Classification of Primary Care Coding (ICPC-2) is being used locally in public primary care settings to document the reasons of their patients' attendances.1,2 The importance of accurate ICPC coding is evident as it generates data for strategic planning of healthcare services which can inform policy-makers on prioritization of quality improvement initiatives.3 Its use is extensive as reported in local studies on morbidity patterns and their seasonal variations 4,5, clinical audits 6, and evaluation of patient characteristics and health services utilization.7 A recent report has also identified important issues in family practice such as consultation patterns of frequent attenders.7 As discussed by Wun YT (2003)8, ICPC coding is well designed and suited for primary care, and its coding in first contact consultations could reveal reasons of encounter that are often intricately hidden. In recent years, initiatives to computerize medical records in the private sector of Hong Kong for the Public Private Interface (PPI) scheme have been important steps towards continuity of care when patients visited both public and private sectors. In this context, complete and accurate coding of ICPC in the public sector should extend its impact to enhance patient care in private settings as well. Since 2005, the Department of Family Medicine, New Territories West cluster of the Hospital Authority had implemented various measures to promote ICPC coding in all of its clinics. Doctors were reminded to code at least one clinical problem for each consultation using ICPC. Information sheets on how to code common clinical problems were available in every consultation room for doctors' quick reference. In addition, doctors could also seek help from personnel who were familiar with ICPC. Furthermore, the clinic and individual doctor's performance in ICPC coding was reviewed every three to six months. Doctors not meeting the department's goal would be interviewed by their clinic supervisors to explore their difficulties and assistance offered accordingly. After three years of continuing efforts, the department achieved almost 100% coding rate of ICPC in both general outpatient clinics (GOPC) and family medicine specialist clinics (FMSC). The GOPC has a higher workload in terms of patient headcounts when compared with that of FMSC. Each doctor needs to see about 10 and 6 patients per hour, respectively. Patients attending GOPC do not usually need referrals. The Patient source for GOPC is largely via self-referred registration through the interactive voice appointment system and follow-up consultations as scheduled by physicians for the chronically ill. On the other hand, FMSC usually takes care of referred patients from multiple sources including the GOPC, Accident and Emergency Department and the private sector. Common reasons of the referrals include psychological morbidities, social problems and complicated chronic diseases. However, although the accuracy and completeness of ICPC coding could be improved by clinical audit,5 it is unknown whether the number of medical conditions in family consultations could be a hindering factor against accurate and complete ICPC coding. Addressing this knowledge gap is essential for future initiatives to improve the completeness and reliability of ICPC coding. In addition, information on common errors associated with ICPC coding is crucial since it provides further clues to enhance coding accuracy. The primary objective of the present study was to evaluate the association between the number of presenting problems and the accuracy and completeness of ICPC coding. Another objective was to explore the common ICPC codes which were used inaccurately or missing as a secondary objective. A "resenting problem" was defined as any condition deviated from normality in any of physical, psychological or social dimensions. We tested the hypothesis that greater number of presenting problems per consultation was associated with inaccurate and missing ICPC codes. Methodology Data Source and Patients This is a retrospective study by case record review in one GOPC and one FMSC randomly selected in the New Territory West cluster. A family medicine specialist offered 10 minutes training sessions on ICPC coding for all doctors on a weekly basis. The methods of entering ICPC codes and the agreed criteria for ICPC entry practices were standardized. Patient records in these two clinics were reviewed during the study period from 01 December, 2008 to 06 December, 2008. The list of patients was generated from the clinical management system (CMS) showing all the attendances in this period. We were able to include all patient records in the FMSC because the weekly patient headcounts were about 500 only. On the other hand, over 2,500 patients were seen in GOPC. Therefore a quasi-random sampling for medical records in the GOPC was adopted such that every fourth record was selected. Records were reviewed on computer but they were anonymized by covering patient's name and identity number on the display screen. Major outcome variables We recorded the details of ICPC codes, the total number of problems per consultation and the number of codes per consultation in these records. Each patient record was judged on its accuracy and completeness of the respective ICPC coding. We used the case notes entered into the computer as the gold standard to evaluate the number of problems identified with reference to the whole text by two independent family medicine specialists. Discrepancy arising during these qualitative reviews was resolved by consensus. In all analysis, each problem was regarded as one unit of analysis. An exception was the analysis of proportion of missing codes versus the number of presenting problems where each case record was used instead as one counting unit. Statistical Analysis The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15.0 (SPSS Incorporation, Chicago, Illinois) was used for all data entry and analysis. We compared the mean number of clinical problems and ICPC codes per consultations, between patients attending the GOPC and the FMSC by student's t-tests. The proportions of case records having accurate and complete ICPC codes were compared between these two clinic settings using chi-square tests of homogeneity. The top eight common missing and inaccurate codes were identified and listed in descending orders. All p values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. Results total of 1,157 medical records were reviewed. 638 case records were retrieved in TSW GOPC and 519 case records in POH FMSC. In FMSC, the mean number of problems managed (2.91 vs. 1.80, p<0.001) and coded (2.01 vs. 1.33, p<0.001) outnumbered those in GOPC. However, GOPC doctors were more accurate than their FMSC counterparts in coding (98.2% vs 90.4% correct, p<0.001) and were judged as having lower missing rates (31.0% vs. 26.9%, p=0.024, see Table 1). Table 1 : Overall results

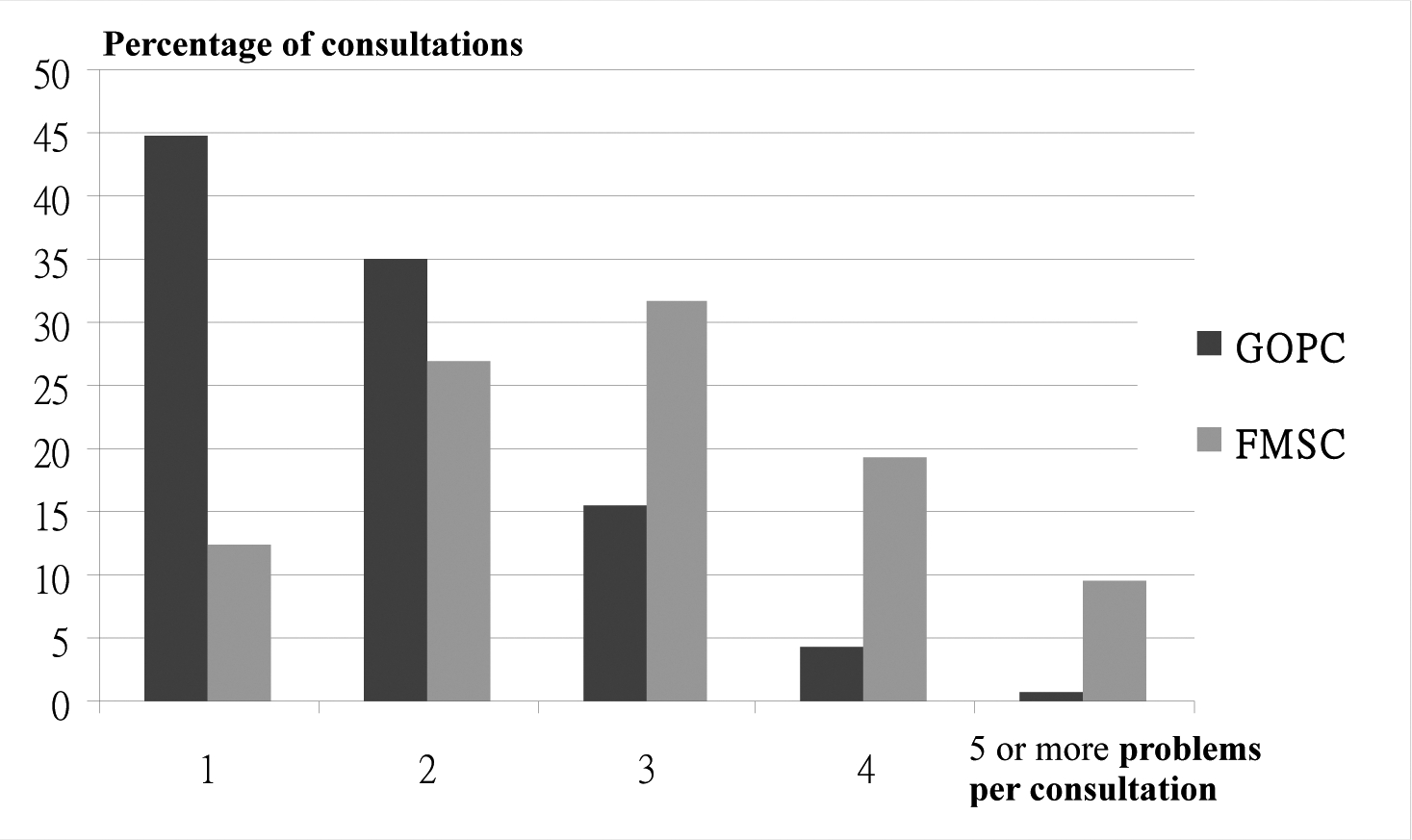

Student's t-tests and chi-square tests of homogeneity were used for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Most consultations in FMSC had multiple problems to tackle (Figure 1). The majority of the case records in GOPC handled one to two problems during the consultation. For the FMSC, most of the consultations involved more than three problems. Figure 1: Comparing complexity of consultations between GOPC and FMSC

In both GOPC and FMSC, the proportion of missing codes per case record increased as the number of problems encountered increased (Figure 2). In GOPCs, the percentages of missing codes remained low at 1.5% when there was one clinical problem but experienced a more observable rise when the number of clinical problems reached two. In FMSC, there were no missing codes when patients presented with only one medical problem and the proportion of missing code increased from 25% to more than 40% as the number of clinical problems increased from two to more than five. Figure 2: Relationship between No. of problems managed and missing codes

The common errors and missing codes were summarized in Table 2 and Table 3 respectively. Obesity (T82), complicated hypertension (K87) and cerebrovascular diseases (K91) were the most common codes reported to be inaccurate, while obesity/overweight (T82/T83), lipid disorder (T93) and tobacco abuse (P17) were the most frequently reported missing codes. Table 2: Top 8 common errors in coding (Decending order)

Tablel 3: Top 8 Missing codes (Descending order)

Discussion While we found in this study relatively high accuracy levels of ICPC coding in GOPC and FMSC settings (98.2% and 90.6% respectively), the proportions of missing codes in both settings remained high (26.9% and 30.0% respectively). FMSC had higher proportion of missing and inaccurate codes when compared with the GOPC setting. Greater number of medical conditions per consultation was significantly associated with both lower accuracy and higher missing coding rates in both GOPC and FMSC. From a systematic review of 24 studies which assessed the quality of computerized records in UK primary care settings,8 five studies investigated the completeness of morbidity codes allocated to consultations, and a high variability of levels ranging from 67% to 99% 9-13 was found. The accuracy of coding also seemed to vary between studies and the medical condition under scrutiny; for instance, coding of diabetes 11,12,14-18 tended to be of higher quality than that of asthma 11,12,14-19 (>90% vs. 70% complete and accurate coding). Limited consultation time could be one of the major causes of missing codes, subsequently contributing to underestimated complexity of clinical encounters and distorted morbidity patterns. For example, the prevalence of psychosocial problems will be undervalued if they are not coded. It is therefore desirable for physicians to record social problems, as discovered in the evaluation of presenting complaints, to be entered in a separate paragraph on psychosocial history to facilitate subsequent ICPC coding. However, consultation time was not investigated in this study. One may argue that doctors may not necessarily spend more time in each consultation although case load in FMSC is less. Therefore, further studies are warranted to correlate consultation time with quality of coding. Some reasons to explain the differences in ICPC coding accuracy between the GOPC and FMSC include the heterogeneity of patient profiles and the nature of patients' presenting complaints. The former setting serves the general public for both episodic and chronic health problems which are in generally more straightforward and familiar to doctors with respect to management. In contrast, the latter setting was more family medicine oriented, providing comprehensive, patient-centred care adopting a more holistic approach. It handles referrals from multiple sources, including the secondary healthcare sector, the emergency unit and the private physicians. These cases usually have numerous, complicated problems; and many have psychosocial issues intermingled with physical complaints, therefore making diagnostic coding more difficult and challenging. Exploration of potential hidden problems towards the end of consultations might be an obstacle for complete coding practices. In this survey, we reported that the FMSC handle more problems (1.80 vs. 2.91) in each consultation and the problems were probably more complicated than that of GOPC. From our experience, we postulated that the completeness and correctness of coding are inversely related with the number of problems, which was now reported by the present study. GOPC did better in correctness probably because they generally had simpler and fewer problems to deal with. For example, over 50 percent of clinic quotas are allocated to serve patients with chronic illnesses. Majority of them are common problems such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and obesity. Physicians working in GOPC can simply repeat the coding in the computer screen. On the other hand, patients attending FMSC may have greater number and variety of physical illnesses and complicated psychosocial problems are more likely to be identified because relatively more time is available in FMSC to adopt a biopsychosocial approach. Coding these complex and versatile problems certainly demands more knowledge and skills from doctors. However, with increased number of problems in consultations, the proportions of missing codes were less for FMSC as compared with GOPC when each medical record was counted as a single unit. This may be due to doctors in FMSC being more familiar with the ICPC coding system as they have undergone more intensive training than their GOPC counterparts. The former has protected study time to attend a five to ten minutes training on ICPC incorporated to the weekly family medicine training seminars, which are mandatory for FMSC doctors. GOPC doctors are encouraged to participate on a voluntary basis. However, their attendance rates have been low, probably because the training is held after office hours and the venue is away from their work places. Also they have more time in coding the problems. There were mainly two issues identified in the reasons for missing codes. Firstly, common clinical situations that we encounter on a regular basis like tobacco smoking and psychosocial problems might be easily disregarded as the reasons of patient attendances. Furthermore, administrative procedures like drug refilling and medication request could be perceived by physicians as problems that do not warrant an ICPC code. For the common errors in coding, the major problem is the non-specific nature of coding; for example physicians tend to use the same coding (K86) for patient suffering from hypertension whether they were uncomplicated (K86) or complicated (K87). The error could be due to several reasons; for instance, the lack of knowledge about different coding and repetition of the same wrong coding from previous consultation for the sake of convenience. This error can be overcome by educational trainings in seminars. The study by Lam et al has also identified similar coding errors in a primary care clinic.6 In the future, more innovative strategies could be adopted, including reminders of the list of correct coding for common medical conditions encountered in family practice placed beside the computer, and continuous promotions for the importance of accurate coding via more effective communication means. This study has several limitations. Firstly, it adopted sampling from two clinics only in one geographical region of Hong Kong, and we have not compared the characteristics of our sample and patients attending the clinics. As a result, its generalizability was limited. We have not adopted a simple random sampling strategy for administrative reasons and this study could be considered as a pilot. Besides, there were other confounding factors which have not been analyzed in this study, including patients' sociodemographic details, consultation time for each visit, doctors' training status, the case load for each doctor and motivational factors among physicians. Critics might argue that the practice of ICPC coding is not compulsory and is non-remunerative; therefore the absence of a formal incentive to complete ICPC coding for each patient might be a significant factor affecting the coding practices. Lastly, this study regarded the case records as the gold standard for which the accuracy and completeness of the ICPC codes were judged; while the case notes might not necessarily be comprehensive and reflective of the real consultations. Key messages

Conclusion In summary this study showed that the number of medical conditions per consultation and the FMSC setting was positively associated with inaccurate and missing coding. To facilitate best practice, it was suggested that more educational initiatives be implemented in these clinic settings to enhance ICPC coding practices, especially focusing on how efficient entry of ICPC codes be conducted in face of multiple medical problems. We recommend a larger scale study which involves a more representative sampling among different primary care clinics in Hong Kong to compare coding practices in different service settings. Future research directions should focus on evaluating the underlying reasons and factors associated with missing and incomplete coding.

Hung-yung Wong, MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Specialist Resident, Edwin YH Chan, MBChB, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Specialist Resident, Liang Jun, MBChB (Glasg), MRCGP (UK), FHKAM (Family Medicine) Family Medicine Consultant and Coordinator, Department of Family Medicine, Community Care Division, New Territories West Cluster, Hospital Authority Martin CS Wong, MBChB, MD (CUHK), FHKCFP, MPH (CUHK) Associate Professor, School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, Chinese University of Hong Kong Correspondence to : Dr Liang Jun, Department of Family Medicine, Community Care Division New Territories West Cluster, Hospital Authority.

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||