|

March 2009, Volume 31, No. 1

|

Original Articles

|

A retrospective study of patterns and outcomes of A&E Department referrals from a Family Medicine Training CentreMing-shing Ng吳明勝, Ken K M Ho何家銘, Ting-kong Poon潘定江, Wing-ngar Cheuk卓穎雅, Alvin C Y Chan陳鍾煜, Yuk-kwan Yiu姚玉筠 HK Pract 2009;31:7-13 Summary

Objective: How common do we encounter emergency conditions in the

General Out-Patient Clinic (GOPC)? How appropriate are we referring patients to

the Accident and Emergency Department (AED)? These are important questions that

need to be addressed for better resource allocation and utilization. This study

aims 1) to find out the spectrum of emergency conditions referred to AED from one

General Practice Clinic (GPC), 2) to consider the appropriateness of the referrals

and 3) to identify areas for improving the appropriateness of AED referrals.

Keywords: Referrals, emergency department, primary health care, appropriateness. 摘要

目的: 在普通科門診遇見緊急病症的頻率有多高?我們轉介病人到急症部門的適當程度高嗎?這是關於資源分配和使用的重要問題。本研究的目的是調查由普通科門診轉介到急症部門病人的種類以及適當程度,藉此改善將來轉介病人到急症部門的適當性。

主要詞彙: 轉介,急症部門,基層醫療,適當性。 Introduction The General Out-Patient Clinics (GOPC) are commonly perceived as clinics tackling only minor diseases like common cold or chronic stable conditions like hypertension or diabetes. One soon changes one mind after having an opportunity to be posted to and performing a day's work in one of the GOPCs. The wide spectrum of diseases encountered in GOPC may include a number of emergency conditions. 7% to 41% of patients, who attended the Accident and Emergency Department (AED), stated that they were earlier seen by their own family doctors or general practitioners and told to go to the AED1 for one reason or another. On the other hand, more than 50% of the workload of an AED in Hong Kong was estimated to be not of an urgent or serious nature.2 We know that there are substantial costs associated with a visit to the AED. Inappropriate referrals will greatly increase the load of the heavily burdened AED and delay the timely management of other urgent and unstable patients. In this study, we aimed at discovering the spectrum of emergency conditions encountered in GOPC and making analysis of the appropriateness of the AED referrals. There is no universal agreement on what constitutes an appropriate AED referral. A local study on the outcome and appropriateness of referrals to emergency department3 had found that 74.5% of the AED referrals from a GOPC were appropriate, based on the criteria of 1) urgent hospital admission, 2) urgent treatment not available at GOPC, 3) urgent appropriate investigation not available at GOPC, 4) urgent referrals to Specialist Outpatient Clinic required, and 5) referrals that require further follow-up treatment by AED. In our study, an appropriate referral was based on two indicators. The first one was based on the process of care, which was modified from the one used by Patel and Dubinsky.1 Their method had been validated by a study by Lowy et al.4 It relied on performance of investigations and interventions required, as surrogate marker for the appropriateness of AED referrals. In their study, questionnaires were filled by the emergency department doctors. Investigations and interventions were counted as medically indicated and urgent: if these were not to be done as a matter of routine; or needed to be performed within 6 hours; or not done solely on the request of the referring physician. The availability of resources for the referring family physician was assessed. If resources were available in the same building as the family physician clinic and investigations could provide same-day results, resources were considered as available to the referring physician. Appropriate referrals were deemed to be those when investigations or interventions were not available to the family physician, and those that the AED physician classified as urgent and medically indicated. Referrals were also deemed to be appropriate if the patient received a specialist consultation in the AED or was admitted to the hospital. By using this process of care method, 75.5% of the referrals in the study were found appropriate. In any health care system relying on a well-developed primary care, the gate-keeping role of the family physician is of paramount importance. The primary care clinics should be well-equipped and supported by easily accessible community resources. It is expected that such clinics will be more selective in referring patients to AED and the criteria for evaluating the appropriateness of referrals may be more stringent. The second indicator used in our study was based on matching the pre-AED diagnosis with the eventual diagnosis. This was more simple but less accurate and gave an impression on the predictive accuracy of the pre-AED diagnosis. Methods This is a retrospective study of the referrals to the AED by doctors of the General Practice Clinic (GPC) of Yan Chai Hospital. GPC of Yan Chai Hospital is a Family Medicine Training Centre of the Kowloon West Cluster. This is a hospital-based GOPC. All the hard copies of the AED referrals from December 2006 to May 2007 were collected. The consultation records of the patients were traced from the Clinical Management System (CMS) to retrieve information to find out: 1) demographics of patients, 2) spectrum of emergency conditions encountered and 3) appropriateness of referrals. The referral letters were reviewed by doctors of the clinic including the referring doctors. Key data Key information being retrieved included: the sex, age, reasons of referrals (matching with the best one in Table 1); whether any investigations, that were not appropriate or not readily available in GPC, were performed ( Table 2-a ); whether any treatment, that was not readily available in GPC, was given ( Table 2-b ); whether hospital admission was arranged; whether the patients defaulted attending AED; whether the patients self discharged against medical advice in the AED; and the final diagnostic impression upon discharge from AED or hospital (matching with the best in Table 1).

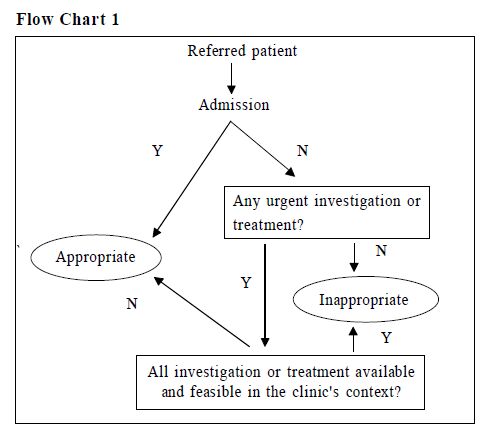

Determining the appropriateness of referrals The appropriateness of referrals was based on two types of indicators of appropriate referrals. They were the process of care and the eventual diagnosis. We have modified the method used by Patel and Dubinsky1 for process of care (Flow Chart 1).

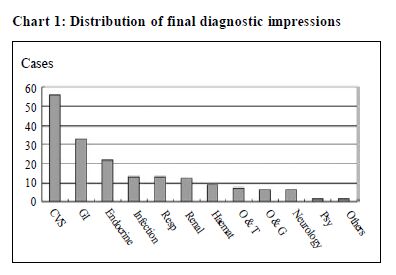

Our method was less stringent as we did not seek the AED physicians' opinions on the necessity of the investigations or interventions performed. An urgent medical condition like acute heart failure undoubtedly warrants AED referral. However, there were clinical situations that were relatively indicated for AED referral when administrative reasons were taken into consideration. We could therefore categorize the appropriateness of referrals into relative (administrative) and absolute (urgent medical needs) ones. The urgent investigations listed in Table 2 were within the realm of what was available to our clinic. Results could be available within a few hours. However, if the investigation results were unlikely to reach the clinic within the operating hours, it was deemed appropriate to refer the patient to AED for management. We considered that referring a patient to the AED for serial ECGs was appropriate as ECG machine was not within the proximity of the clinic and the patient had to travel to other areas of the hospital for this. Similarly, we had also considered the limitation of manpower and time in determining the appropriateness of giving treatment or management in GPC. We could not afford prolonged observation of patients outside the operating hours of the clinic, so we needed to send the patient to AED for further observation of potentially serious or unstable conditions. Some procedures like suturing or incision and drainage of abscess may not be affordable by a busy outpatient clinic. Matching the diagnostic impressions Another method used for evaluating the appropriateness of AED referral was based on the eventual diagnosis. This method was less accurate but was used as another indicator in our study. The diagnostic impressions of the referring doctors and the diagnoses upon discharge by the AED doctors were categorized according to the systems involved and disease subtypes. The percentage of cases when the diagnoses matched was calculated. Results We referred 189 patients to the AED during the study period. The AED referral rate was 0.69%. The age of these patients ranged from 8 months to 100 years old with the mean of 61.7 years. There were 98 females (51.9%) and 91 males (48.1%). Three patients referred did not attend the AED and their conditions were stable on following up in our clinic. Seven patients DAMA (Discharged against medical advice) at AED. On excluding patients who defaulted attending AED or DAMA at AED, the following rates were observed: Hospital admission 69%; urgent investigation and treatment, not appropriate or not readily available in GPC, 40% and 43% respectively. The percentage of appropriate referral was 91% based on the process of care. The diagnostic impression of the referring doctor matched with the final diagnosis in 84% of the cases. Chart 1 shows the frequency distribution of the eventual diagnostic impression. The top five reasons of referral were poor control DM (12%), poor control hypertension (10%), anaemia (6%), acute coronary syndrome (6%) and abscess (5%) (Chart 2).

Discussion As we can see, there was a wide spectrum of urgent conditions encountered in our clinic. These covered almost all of the specialties. The AED referral rate was 0.69% which was relatively higher than the 0.2% in Cheung Sha Wan GOPC. This can be explained by the characteristic of patients seen in a hospital-based GPC. Hospital-based GPC may attract more patients with multiple medical diseases or more complex conditions. Proximity of the clinic to the AED may also encourage doctors to refer patients with borderline conditions to the AED for further management. Cases encountered in GOPC is challenging as reflected by this study. Patients are referred to the AED for various reasons including 1) stabilization of unstable conditions, 2) hospital admissions, 3) monitoring of potentially serious conditions, 4) urgent investigations and 5) urgent treatments. A referral is considered to be inappropriate if the condition can be easily dealt with by the referring doctor. When determining whether a referral was appropriate or not, we also considered other aspects like clinic setting, manpower, time constraint, doctors and patient factors. These administrative reasons were considered as relative indications for referral. A patient with suspected fracture may be discharged home after taking the wet film either at GOPC or AED. GOPC has more time constraints while AED has less. A trainee may have more "inappropriate" referrals compared with a trainer.5 Unresolved request from the patient may also result in a referral. A number of studies have been performed to determine the appropriateness of the AED visit by self-referred patients. 18% to 89% of these visits were classified as unnecessary.6 This wide variability may be explained by the differences in the study population, but more importantly, by the assessment method. Two strategies are commonly used to determine the appropriateness of AED referrals. The first one is based on the eventual diagnosis. The eventual diagnosis is matched with the referrer's diagnosis. The clinical management needs, as implied by the diagnosis, are evaluated. If they are not beyond the resources available in the practice, the referrals are deemed inappropriate. In our study, the initial diagnostic impression matched with the eventual diagnosis in 84% of the cases. This was a simple comparison without evaluating the management needs implied by the diagnoses. Therefore, it was less accurate. We also modified the "process of care" from Patel and Dubinsky1 as the key indicator for propriety of AED referrals. All the information was retrieved from the referral letters and the computer records. There was a lack of communication with the AED physicians. Therefore, we cannot differentiate those investigations which were done urgently as indicated versus those done as a routine or done as requested by the patients. This may result in a falsely high rate of appropriate referrals. One solution to solve this problem is to record down the indication of the investigation and intervention by the AED physicians. Other pitfalls of our method include judgmental bias by the assessors, strong interventional bias in the AED compared with most outpatient settings, the changes of patients' presentation during the travel to AED and possibility of patients' exaggeration of their symptoms in AED to justify their presence in the AED. We could not directly compare the appropriate rate of referrals among the studies due to differences in the stringentness of the selection criteria for appropriateness and bias in judgment. Moreover, our recruitment of administrative reasons as relative indications for referrals would contribute to a higher overall appropriate rate of referrals. There is still a lack of universally agreed or validated method for evaluation of the appropriateness of referrals. This makes comparison between different studies difficult. Further research on the measurement of this important health-care outcome is needed . Strategies for improvement of the appropriateness of referrals could focus on enhancement of doctor's clinical competency and clinic's resources. The comprehensive training programme of family medicine includes rotating through different specialties. This increases the trainees' competency in his/her management of a wide variety of cases. Better control of chronic conditions like hypertension and diabetes will definitely reduce referrals. Establishment of clinical protocols or guidelines may also result in an improvement of the quality of patient care. Carrying out of referral audits may also improve the quality of referrals. Unnecessary referrals caused by administrative problems may be reduced by improving the resources available to a clinic in terms of manpower and facilities. Key messages

Ming-shing Ng, MBBS (HK), Dip Med (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP

Ken KM Ho, MBBS (HK), Dip Med (CUHK) Ting-kong Poon, MBChB (CUHK) Wing-ngar Cheuk, MBChB (CUHK), Dip Med (CUHK), DCH (Ireland) Residents, Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, Kowloon West Cluster Alvin CY Chan, MBChB (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Senior Manager, Primary & Community Care, Hospital Authority Head Office, Hong Kong SAR Yuk-kwan Yiu, MBBS (HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Consultant Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, Kowloon West Cluster Correspondence to : Dr Ming-shing Ng, General Practice Clinic, Yan Chai Hospital, Tsuen Wan, NT, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|