|

September 2009, Volume 31, No. 3

|

Original Articles

|

A pilot study of acceptability of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine among women of reproductive ages in Hong KongTsun-kit Chu 朱晉傑, Xin-hua Zhang 張新華, Jun Liang 梁峻 HK Pract 2009;31:109-119 Summary

Objective: This study investigates the acceptability, i.e. the proportion

of local Chinese women who would accept HPV vaccination for their daughters, if

they now have or will have a daughter in future. It assesses the level of knowledge

of HPV infection and HPV vaccine, and attitudes towards HPV vaccination among respondents.

Keywords: Human Papillomavirus (HPV), vaccine, acceptability, knowledge, attitude 摘要

目的:本研究調查可接受性,即本地中國女仕同意其女兒 (假 如她們現在或將來會有女兒) 接受人類乳頭狀病毒疫苗的百分 比,並且評估回應者有關人類乳頭狀病毒感染及疫苗知識,

瞭解她們對人類乳頭狀病毒疫苗的態度。

主要詞彙:人類乳頭狀病毒,疫苗,可接受性,知識,態度 Introduction The development of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is a major breakthrough in cancer prevention, as it is the first vaccine that could protect women against cervical cancer, and should preferably be given in adolescence before initiation of sexual activity.1 The Centers of Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have determined that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine is safe to use and effective in preventing four types of HPV which most commonly cause cervical cancer and genital warts. Acceptance and uptake rate of HPV vaccine would determine its success. Overseas studies have assessed populations' acceptability towards the vaccine, 2-4 but locally there is a lack of such data. Despite widely promoted by pharmaceutical companies, HPV vaccination has not be en included in the local go vernme nt's subsidized vaccination programme. High degrees of acceptability (up to 80% to 90%) had been demonstrated in different overseas countries. 3,5-7 Quantitative 3,6, 8-10 and qualitative11 studies have identified a number of factors that could influence women's acceptance of HPV vaccination for their daughters, such as lack of knowledge of HPV infection, fear of social stigma, and perception of HPV vaccination leading to risky sexual behaviour in their daughters. 6, 11-12 This study investigates the proportion of local women who accept HPV vaccination for their daughters, and their knowledge level on HPV infection and HPV vaccination. Also, it investigates local women's attitudes and concerns towards HPV vaccination, and their association with vaccine acceptance. Method This study was a cross-sectional study carried out in one primary care family medicine centre in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. A random sample of mentally competent Chinese women aged 18 to 50 attending the clinic was invited to participate in this study within the period from March 2008 to April 2008. Exclusion criteria included Chinese women who are younger than 18 or older than 50 years, or not be able to give consent. A structured questionnaire was designed for this study as there had been no validated Chines e questionnaire to assess the level of knowledge on HPV infection, nor attitudes and acceptance towards HPV vaccine prior to start of this study. Acceptability of HPV vaccination was evaluated using a 5-item response question. There were 25 questions to assess their knowledge on: consequences of HPV infection, mode of HPV transmission, indication of Pap smear, risk factors of HPV infection and cervical cancer, and efficacy of HPV vaccine (Appendix 1 & 2). Fourteen out of these 25 questions originated from a validated questionnaire in assessment of HPV knowledge among University students (Yacobi, 1999). 13 The number of correct responses to thes e questions formed a knowledge score for each individual. Attitude towards HPV vaccination was assessed by six questions on: participants' perceived susceptibility of their daughters to HPV infection, their concerned factors about consent to HPV vaccination for their daughters, their perceived moral risks (stigmatization and false sense of security) towards HPV vaccination, their opinions towards universal HPV vaccination, and their acceptability if it was given before their daughters became sexually active. An anonymous s elf-administered questionnaire written in Chinese was distributed to each participant by clinic nurses before doctor consultation. Nurses explained the purpose of this study, its voluntary nature and confidentiality of data obtained to all participants under a standardized protocol (Appendix 3), and obtained their oral consent. The principal investigator provided on-site explanation for any participant who had difficulties in understanding the questionnaire. Participants put their completed questionnaires into a collection box by themselves. Sample size estimation was based on detecting 80% local mothers who accepted HPV vaccination for their daughters according to the survey by Woodhall et al. (2007). 6 Using the desired precision as 0.05, the estimated sample size was 246. The following formula was used:

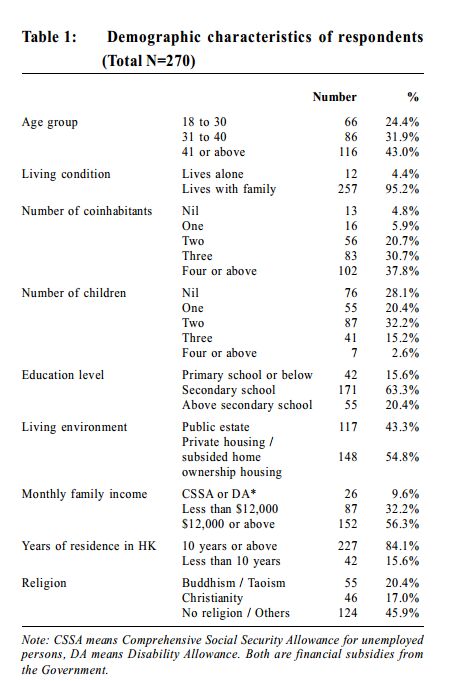

In statistical analysis, acceptability of HPV vaccine was employed as categorical dependent variable to evaluate its association between respondents' demographic variables, knowledge and attitudes towards HPV vaccination. A knowledge score was calculated and used as one of the independent variables. Odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals were obtained using binary logistic regression model SPSS version 16.0. Results 313 questionnaires were collected, with a response rate of 43.7%. The analysis consisted of 270 women, as 43 women were excluded because of incompleteness of the information. 74.9% of those analysed were aged above 30, and 70.4% of them had one or more children. Detailed demographic characteristics of respondents were shown in Table 1. 67.8% of respondents had had history of previous Pap test. 12% (n=31) and 1% (n=3) of them had had history of abnormal Pap test and cervical cancer respectively. Women were asked whether they would allow their children to have HPV vaccine. 71.5% of respondents belonged to the "accepting" group, as 39.3% (n=106) and 32.2% (n=87) of them answer "yes" and "probably yes" to the question respectively. Those indicated "don't know" (21.1%, n=57) "probably no" (2.6%, n=7) and "no" (3.7%, n=10) were classified into the "not accepting" group. With regard to HPV vaccination policy, 56.3% of respondents accepted universal HPV vaccination and half of them preferred their daughters having HPV vaccines before becoming sexually active. On the other hand, 5.6% of them disagreed with universal HPV vaccination while 7% of them would refuse to allow their daughters to have HPV vaccine before becoming sexually active.

Respondents had fair knowledge on HPV infection and HPV vaccination. 45.2% of them had heard of HPV. Only one third (33.7%) of them correctly responded that HPV was a virus that could cause cervical cancer. 52.6% of them knew that having multiple sexual partners would increase risk of HPV infection. 57.4% of respondents had heard of the HPV vaccine. 44.8% and 48.1% of them understood that such vaccine could give protection against cervical cancer and HPV infection respectively. However, half of them were unsure about its efficacy (51.1% were unsure about its protection against cervical cancer and 49.6% were uncertain about its protection against HPV infection). A knowledge score was calculated using 25 questions assessing the knowledge level of HPV infection and HPV vaccine for each respondent, with maximum score of 25 if all questions had been correctly answered. Mean knowledge score among respondents was 8.9 (standard deviation was 6.64). Women were asked about their perceived susceptibility of HPV infection and attitudes towards the possible stigmatizing or false-reassuring effects of HPV vaccine for their daughters. Majority (64%) of them did not know about their daughter's susceptibility. 12% of respondents believed their daughters were susceptible to HPV infection (Table 2). Only 18% of respondents were worried about HPV vaccination giving a false sense of security and leading to unsafe sexual behaviour in adolescents. 5.2% of respondents thought that HPV vaccination promoted promiscuity among women.

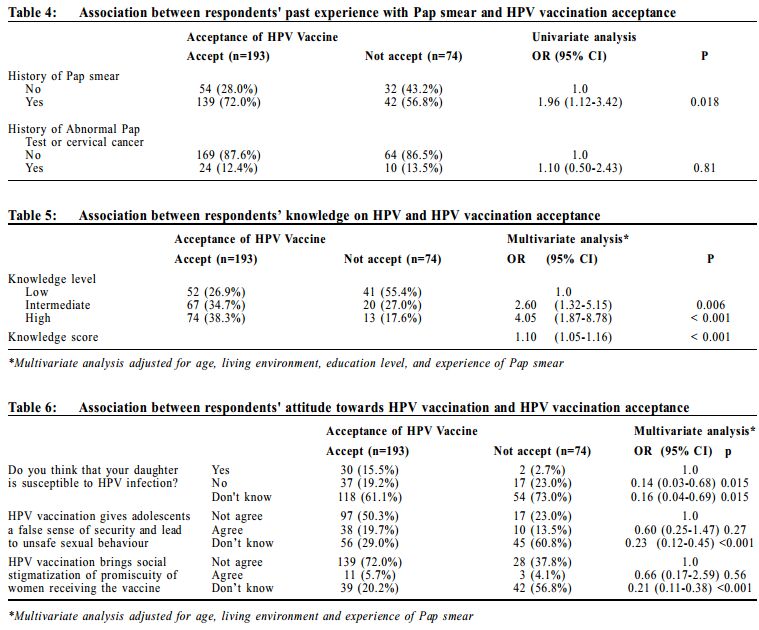

Women were asked to rank the following factors, in order of importance, which may affect their consideration in allowing their daughters for HPV vaccination, namely, vaccine safety, vaccine side effects, religious beliefs, vaccine efficacy and cost. Among the 5 options listed,respondents were most concerned about vaccine safety, with 37.8% of them ranked it as their most concerned consideration (Graph 1). 83% of respondents expressed that they would like to know more about HPV vaccination. Majority (74%) of respondents would like their daughters to know more about HPV vaccination and sexually transmitted diseases (STD). 27% of respondents had difficulties talking with their daughters about STD. Only 7 respondents (2.6%) were reluctant to know more about HPV vaccination, or let their daughter to do so. Majority of respondents wanted to receive education on HPV vaccination from their family doctors. Women were asked to rank in order of importance sources of recommendation from which they would seek before consenting to HPV vaccination for their daughters. 71.5% indicated recommendation from their family doctors was the most important, while only 14.1% and 2.6% of them indicated that the media and girls' father respectively were their most wanted source of recommendation. Factor s re lat ed to the ac c eptanc e of HPV vaccination In univariat e logistic regression analysis, all demographic variables showed no significant association with acceptance of HPV vaccination (Table 3). Women who accepted HPV vaccination for their daughters were more likely to have had Pap test done before (odds ratio [OR] 1.96, 95% CI 1.12-3.42). There was no association between past experience of abnormal Pap test and HPV vaccination acceptance (Table 4).

To analyze the relationship between acceptability and knowledge on HPV, respondents were grouped into 3 knowledge levels, namely low level (0 to 4 questions out of 25 questions on HPV knowledge were correct), intermediate level (5 - 12 questions correct), and high level (13 - 25 questions correct). Each level consisted of one third of the total number of respondents. In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, living environment, education level and experience of Pap smear, women who accepted HPV vaccination for their daughters were more likely to have a higher knowledge level (OR 4.05, 95% CI 1.87-8.78) (Table 5). The relationship between acceptability and respondents' attitudes was explored. Women who were unsure whether HPV vaccination would bring social stigmatization (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.11-0.38), or who were uncertain whether it would result in risky sexual behaviour in their daughters (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.12-0.45), and who perceived low susceptibility to HPV infection in their daughters (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03-0.68), were less likely to accept HPV vaccination (Table 6).

Women who were resistant to univers al HPV vaccination policy (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08-0.94), or those who disagreed with vaccinating their sexually inactive daughters (OR 0.10, 95% CI 0.03-0.32), were consistently less likely to accept HPV vaccination for their daughters (Table 7).

Discussion Acceptability of HPV vaccine This study demonstrated that local women may have a high acceptance rate of HPV vaccination for their daughter, which is comparable with overseas studies (ranging from 80% to 90%).3, 5-7 The lack of association between HPV vaccination acceptance and socio-demographic factors was shown in this study. Similar absence of association was found in a previous large scale study in the United Kingdom5 , although this study might be biased by a large proportion of respondents in low socio-economic class and low education background. Association between knowledge and acceptability It had been shown by Davis et al (2004)2 that a better understanding on HPV was associated with a higher level of awareness about HPV infection. The current study population had a fair knowledge on HPV and HPV vaccine. The lack of awareness about the link between HPV and cervical cancer was found in this study, which was also found in the United Kingdom5 . Results of this study reflected knowledge deficiency on HPV infection and cervical cancer prevention among local women. Our results also suggest that better knowledge on HPV infection and HPV vaccine could enhance vaccine acceptance. This had been echoed in overseas study where brief educational intervention such as providing a HPV educational fact sheet could improve HPV vaccination acceptance. 2 The majority of respondents were interested to know more about HPV and HPV vaccine despite their lack of knowledge about HPV. Their most wanted source of information was from their family doctors. The role of family doctor in HPV vaccine uptake and cervical cancer prevention in the community is important. To achieve a high uptake and acceptance rate a coordinated intervention in ed ucating the public about HPV infectio n and vaccination should be designed in a family practice setting as well as in the community level. Association between attitudes and acceptability This study showed that a low perceived susceptibility to HPV infection and high perceived moral risks of HPV vaccination reduce the acceptability of HPV vaccine. Such association had been demonstrated in previous studies as well.3, 5, 6, 14 The perceived moral risk of HPV vaccination among women in this study, similar to that observed by Barbin et al5 was described as giving adolescences a false sense of security and promoting unsafe sexual behaviour such as early initiation of sexual activity, as well as social stigmatization of promiscuity in women receiving HPV vaccine. Women's perception on HPV susceptibility and moral risks of vaccine to their daughter could be affected by their knowledge on HPV, peer influence, and other complex cultural and traditional values. These health beliefs would influence their health behaviour towards HPV vaccination. Therefore, when promoting HPV vaccination, health educators should help local woman not only to understand the benefits of HPV vaccination, but also to explore their perceptions on HPV susceptibility and handle their concerns on perceived moral risks of HPV vaccination. This study addressed a small subgroup of women in the "not accepting" group who were resistant to either vaccinating their sexually inactive daughters or universal HPV vaccination policy. Their preferred timing of vaccination and barriers to parental consent of universal HPV vaccination should be investigated in future studies. Local women's concern about HPV vaccination Respondents from this study concerned more about HPV vaccine safety and side effects rather than its efficacy. Effective communication to address these concerns during doctor consultation would enhance the introduction and explanation of HPV vaccination to local women. Furthermore, such concerns can help health promoters to deliver HPV vaccine information that attract lo cal women's a tten tio n. Wh ile the majority of respondents wanted their daughters to know more about s exually transmitted dis eas es (STD), 27% of them expressed difficulties in talking with their daughters about STD. This might be the effect of traditional Chinese culture regarding sex and STD as taboos. Although there was no consensus whether prior discussion of sexuality with recipients should be required before administration of HPV vaccine, discussion on HPV vaccination would provide a valuable platform for sex education. Such discussion preferably should be delivered to adolescents in an organized, coordinated effort among parents, school and health care sectors. In family practice, discussion on HPV vaccination would be a valuable opportunity for anticipatory care and sex education in young women. Study limitations Selection bias was present in population sampling, which was further complicated by the undetermined characteristics of non-responders. Subjects who were excluded because of completion error of questionnaire might rep res e nt a group of res pon dents who h as difficulties in understanding the questionnaire but were reluctant to seek for clarification. Explanation of the questio nnaire by th e principal investigator might possibly introduce answer to respondents who asked for clarification. The majority of respondents were in the low socio-economic class with low education level, which was not representative of the local population. The small number of women who rejected HPV vaccine, and those who were unsure about HPV vaccination for their daughters were grouped together in the same "not accepting" group for analysis. Differences might exist between the two groups. Finally, the validity of the questionnaire has yet to be determined. Conclusion The acceptability of HPV vaccination among local women for their daughters was high (71.5%) in this study population and was comparable with results of overseas studies. Factors associated with acceptance of HPV vaccine among local women identified in this study would be useful in HPV vaccine promotio n an d education in patient care in family practice. Their low awareness and inade quate knowledge to HPV infection, and their concerns about vaccine safety and side effects might guide future public health educational programme on cervical cancer prevention in the community. Acknowledgement The study was funded by the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians Research Fellowship 2008. The investigator would like to acknowledge the help of clinic consultant Dr Liang Jun and associate consultant Dr Chan Laam in allowing this study to take place, and all the clinic staff and patients who participated in it.

Tsun-kit Chu, MScWHS (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP

Resident Jun Liang, MRCGP(UK), FHKAM (Fam Med) Consultant Department of Family Medicine, New Territories West Cluster, Hospital Authority Xin-hua Zhang, MD, PhD Assistant Professor Department of Community and Family Medicine, School of Public Health, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Correspondence to : Dr Tsun-kit Chu, Department of Family Medicine, Pok Oi Hospital, Yuen Long, NT, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|