September 2010, Volume 32, No. 3 |

Update Article

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Management of steroid sensitive nephritic syndrome in children: roles of general practitionersKeith K Lau 劉廣洪, Steven Arora, Clodagh Sweeney HK Pract 2010;32:137-141 Summary The roles of general practitioners in management of childhood nephrotic syndrome:

摘要 全科醫生在診治兒童腎病綜合症的角色包括:

Introduction Nephrotic syndrome is a kidney disorder characterized by oedema, heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminaemia and hyperlipidaemia (Table 1). Untreated nephrotic syndrome is often associated with increased risks of life-threatening infection, thrombosis and dyslipidaemia. The aetiologies and management of nephrotic syndrome in children are different from their adult counterparts and general practitioners who manage patients in different age groups need to be aware of these differences. As clinical response to corticosteroids can give much more significant prognostic indications than the underlying histology can, and the majority of children with nephrotic syndrome are sensitive to corticosteroids, renal biopsy is not usually needed at the onset.

Pathogenesis The common primary and secondary causes of nephrotic syndrome are shown in Table 2. Although genetic mutations leading to disruption of the integrity of the podocyte cytoskeleton have been reported in some patients with nephritic syndrome,1 the exact pathomechanism of nephrotic syndrome still remains uncertain. Circumstantial evidence suggests that perturbations of cell mediated immunity may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of nephritic syndrome.2 Furthermore, there is also clinical and laboratory evidence that a circulating “permeability” factor exists and may be responsible for the increase in permeability of the glomerular basement membrane, but the factor has not yet been identified.3

Epidemiology The incidence of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome among children under the age of 16 has been reported to be between 2 to 7 per 100,000 children per year.4 According to the statistics report from the Hong Kong Government in the year of 2009, the number of children in Hong Kong with age under 15 was 865,000.5 Therefore, the annual incidence of nephrotic syndrome among Hong Kong children is expected to be between 17 to 61 children per year. This number is in line with the reported data from the Hong Kong Paediatric Nephrology Society. According to their database, the annual incidence of nephrotic syndrome among children in Hong Kong was 57 per year during the period of 1998 to 2000 (range 43 to 69).6 Roles of general practitioners To recognize the presenting features of childhood nephrotic syndrome Oedema is the predominant presenting feature in children with nephrotic syndrome. Its pathogenesis remains controversial. Oedematous swelling usually develops around the eyes initially, which is often mistaken as allergy. If left alone, the swelling becomes generalized to involve the whole body. Patients and their families may also notice progressive abdominal distension, decrease in urine output and frothy urine. Physical examinations may reveal marked increase in body weight, pleural effusion and ascites. Urinalysis shows heavy proteinuria and occasionally haematuria. Laboratory investigations that are helpful at presentation are shown in Table 3. As twenty-four hour urine collections are not very practical with children and unnecessary in most children with nephrotic syndrome; proteinuria may be quantified as the protein to creatinine ratio on a randomly voided sample.

To detect atypical features at presentation Minimal change disease is by far the commonest childhood nephrotic syndrome.7 The presence of any of the clinical features, shown in Table 4, suggests a possibility of alternative diagnosis. These children are less likely to respond to corticosteroids therapy and should be referred to paediatric nephrologists. On the other hand, microscopic haematuria may be present in up to 25% of children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome and should not be a contraindication to empirical corticosteroids therapy.8

To initiate medical treatment in children with typical presentation Several studies in the past have determined that among children with nephrotic syndrome, 70 to 80% had histological diagnosis of minimal change disease.9, 10 Since we no longer perform renal biopsy on every child at presentation, we are not able to replicate those studies anymore. Nonetheless, the study from the Hong Kong Nephrology Study Group reported that, among 75 children with biopsy due to nephrotic syndrome between the years 1991 to 1993, 49% had minimal change disease.11 Therefore the majority of children with nephrotic syndrome are still very likely to b e sensitive to corticosteroids treatment. In the absence of atypical features, and if family physicians are comfortable to assume the care, these children can be managed in a family practice setting with an empirical course of treatment without a renal biopsy.

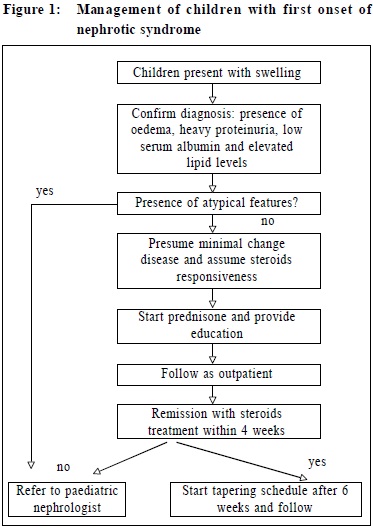

Families need to be taught on how to perform urinalysis for home monitoring. They should keep a clear record of urinalysis, medications given and any medical symptoms experienced. It is important that the caretakers know how to contact the appropriate medical staff in the case of a relapse. A relapse is defined as recurrence of proteinuria (three consecutive days of 2+ or greater proteinuria on urinalysis). To provide routine health maintenance care Children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome are considered immunosuppressed if they have received daily steroids for more than one week in the previous three months, and live vaccines should not be given until at least one month after discontinuation of the corticosteroids. According to the newly revised vaccine schedule for children in Hong Kong, the only live vaccine that are contraindicated in children with active nephrotic syndrome is the MMR.15 Although no guidelines are available, and there are some concerns regarding suboptimal sero-con version, there is no absolute contraindication to giving “non-live vaccines” while the child is on steroid. At our centre, we emphasize immunization for every child; we encourage all our patients with nephrotic syndrome to receive their regular vaccination while they are in remission, including immunizations against varicella and pneumococcus. Although most children suffering from the influenza virus infections will have uneventful recovery, children with active nephrotic syndrome on treatment, as well as those who have been on steroid or other immunosuppressive treatments within the last three and six months respectively, are more prone to suffer complications of their illnesses. Therefore children with nephrotic syndrome should be offered influenza vaccination before the influenza season arrives. During an outbreak, if they develop signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract disease, especially with clinical deterioration, they should be offered antiviral treatment, ideally within 48 hours of symptoms onset. To monitor progress and complications According to a recent study from Hong Kong with a mean follow-up duration of 10 ± 3 years, only 17% of children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome did not have any relapse,16 and up to one third of the relapsers still continued to have active disease at the end of the study. It cannot be overemphasized that families should be informed about the likelihood of relapses in children with nephrotic syndrome, thus they will not feel guilty and have the impression that they have not done enough to prevent it. Other studies also showed that approximately 80% of children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome will relapse one or more times, while some relapse frequently or become steroid dependent. These children should be referred to a paediatric nephrologist for further management. Nevertheless, even children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome are prone to have complications. This is related to the perturbation of the innate system and medication side effects. They have increased predisposition to common infections including cellulitis, upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia. Another major infectious complication is peritonitis. Families should be instructed to seek medical attention if the child is sick. Although it may be due to gastric irritation secondary to corticosteroids, peritonitis should be considered in every child presenting with an acute abdominal pain, especially if accompanied with fever. They are also at an increased risk of thrombosis but current literatures do not support routine use of anticoagulants. However, immobilization, volume depletion and diuretics should be avoided because of the increased predisposition to thrombosis. Hyperlipidaemia in most children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome is usually transient, although it persists in children with resistant nephrotic syndrome, which may potentially contribute to cardiovascular morbidity in adulthood. Therefore, children with nephrotic syndrome should be encouraged to adopt a low fat diet. To decide when to refer to paediatric nephrologist The short- and long-term prognosis of children with steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome is excellent. If the general practitioner feels comfortable, it is not necessary to refer every child to a specialist. However, under certain circumstances, especially if the nephrotic syndrome becomes difficult to manage, the care should be shared with a paediatric nephrologist. Figure 1 depicts an algorithm on when a child should be referred to a paediatric nephrologist.

Conclusion Childhood nephrotic syndrome is not an uncommon condition, and general practitioners should be aware that the management of such condition in children is different from adults. In most instances, children with nephrotic syndrome can be given a course of corticosteroids without a renal biopsy. However, in the presence of atypical features and if the management becomes difficult, it is always prudent to share the care with a paediatric nephrologist. Key messages

Keith K Lau, FHKAM (Paed), American Board of Pediatrics (USA), American Board of Pediatric Nephrology (USA), Steven Arora, MD, FRCPC (Canada) Clodagh Sweeney, MBBCh, BAO, BSc(Hons), MRCPI Correspondence to: Dr Keith K Lau, 1200 Main Street West, HSC 3A50, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8S 4J9. References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||