December 2012, Volume 34, No. 4 |

Update Articles

|

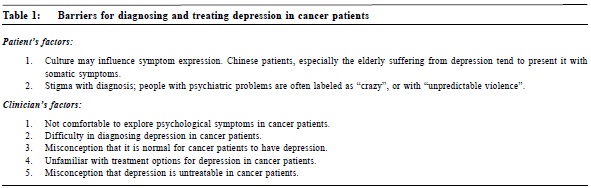

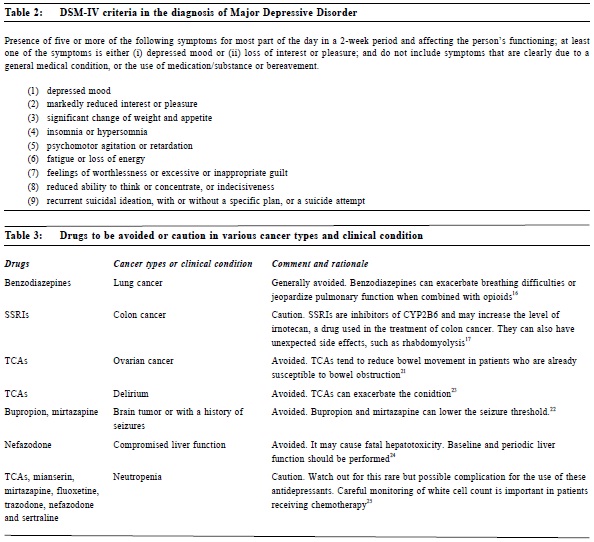

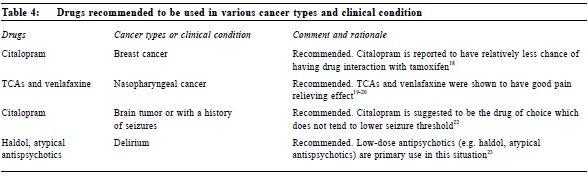

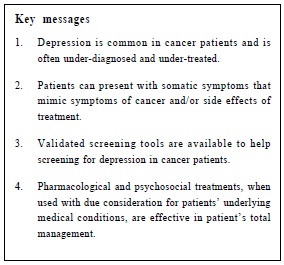

Management of depression in cancer patients?Yin-ying Ma 馬燕盈, Ki-yan Mak 麥基恩 HK Pract 2012;34:154-159 Summary Depression is common in people with cancer. Disabilities arising from it or depression itself can be quite severe and its consequence includes poor quality of life, poor adherence to anticancer treatment, resulting in poor survival and even increased suicide risk. However, depressive disorders in cancer patients are very often under-diagnosed and under-treated by family physicians, especially in busy settings. Diagnosis of depression in cancer patients can be challenging as the patients may present with somatic symptoms, which closely mimic symptoms of cancer and/or its treatment. Indeed, validated screening tools have been developed to facilitate diagnosis and pharmacological and psycho-social treatments have been shown to be effective to treat depression in cancer patients. 摘要 抑鬱症是一種在癌症病人中常見的病症。它不但對病人的生活素質構成負面影響,令病人不願接受抗癌冶療,減低生存機會,而且還會增加自殺的風險。基層醫生經常漏診抑鬱問題以致並未能提供足夠治療,在較繁忙的醫療機構中尤甚。雖然病人常表現為不同系統的軀體症狀,與癌症及其治療表徵相似,導致確疹上的困難,但是隨著篩檢公具的廣泛應用,相信會幫助基層醫生進行初步篩檢。現代療法是綜合性的,包括藥物、心理和社會治療,而其效果亦多數令人滿意。 Introduction Depression is common among cancer patients, which reduces quality of life, reduces adherence to treatment, increases suicide risk, predicts poor survival and places considerable psychological burdenon carers and family members.1 Moreover, depression is very often under-diagnosed and under-treated in our population.2 Prevalence of depression in people with cancer The reported prevalence of depression varies widely (major depression 3% to 38%; depression spectrum syndromes 1.5% to 5 2%) 3 because of differences in the conceptualization of depression, in diagnostic criteria and methodological approaches to the measurement of depression, in populations groups, in types and stages of cancer. There are few large local studies investigating the prevalence of depression in people with cancer. One recent study on 108 subjects with nasopharyngeal cancer treated with radiotherapy showed that the point prevalence of depressive disorder is 22.2%.4 Another local study demonstrated that depression is common among breast cancer patients at the early post-operative stage.5 Cancer types associated highly with depression include brain, pancreas, head and neck, breast, gynaecological and lung.6 Recognition and screening method of depression in cancer patients Barriers in diagnosing depression among cancer patients Very often, depression is under-diagnosed in this population. The reasons behind are complex and often multifaceted. Table 1 summarizes the factors that may be involved. Identifying major depression in cancer patients Al though DSM- IV has been considered the gold standard in the diagnosis of major depression (Table 2),7 the use of it alone may be less predictive in cancer patients because somatic symptoms also mimic physiological symptoms of cancer8 or its treatment. Recently, a study on the symptom indicator for severity of depression has shown that alternative approaches such as the Cavanaugh and Endicott criteria may be better markers for evaluating depression than DSM-IV in cancer patients. “Fearfulness or depressed appearance on the face or body posture” and “brooding, self-pity or pessimism” are suggested to be good markers for mild major depressive disorders; “not participating in medical care and social withdrawal” is suggested for moderately severe major depressive disorders; and “cannot be cheered up, doesn’t smile, no response to good news or funny situations” are suggested for severe major depressive disorder.9 Screening for depression in cancer patients Family physicians can be overwhelmed by the great number of screening tools for depression. An ideal screening tool should have good psychometric properties but, at the same time, not too lengthy.10 Generally speaking, brief depression screening tools are more suitable for cancer patients. There is also evidence that brief screening tools were just as good as long questionnaires. The single question, ‘‘Are you depressed?’’ was demonstrated by Chochinov et al11 to be reliable for screening depression in terminally ill patients. The two-question screening method offered by Hoffman and Weiner, ‘‘Have you been feeling down, depressed, or hopeless in the last month?’’ and ‘‘Have you been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?’’ was also shown to be quite reliable.12 The above approaches have been recommended by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) for use in United Kingdom’s primary care.13 Treatment It is important to rule out reversible organic causes of depression before commencing treatment, and adequate history and examination is mandatory. Pharmacological treatment There is good evidence for the efficacy of antidepressants in the treatment of cancer patients. When using antidepressants in this group of patients, doctors should be aware of their side effects, potential drug interactions with anticancer agents and their potential as adjuvant therapy for other cancer-related symptoms. 1. General guidelines a) Start low (dose) and go slow.

b) Inform patients that in general there is a delayed onset of action, usually takes 2-4 weeks.

c) Maintain the patients on antidepressants for six months to one year to reduce the risk of relapse.

d) Avoid sudden cessation of antidepressants, instead should tail them off gradually to minimize symptoms of discontinuation.

e) Watch out for drug-drug interaction.

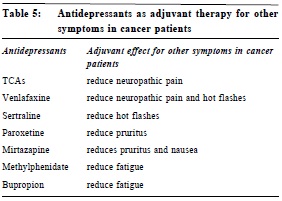

2. Profile and side effects of antidepressants Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Serotonin and Noradrenaline Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRIs) have been suggested to be first-line agents as they are relatively safer and with fewer side effects.14 In contrast, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are less preferred due to its anticholinergic side effects and potential to induce cardiac arrhythmias. Generally speaking, Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs) are contraindicated as they can cause dangerous hypertensive crisis with food and drugs. Psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate, have been suggested for use in cancer patients with short life expectancy.15 The advantages of psychostimulants include: faster onset of action (between 1-7 days); improve appetite, mood and cognition; potentiate analgesic effects and at the same time negate sedative effects of opioids. Nevertheless, they can cause tremor, increase in blood pressure or pulse rate, rarely dyskinesia and aggravation of underlying confusion and psychosis. Some people may feel concerned about the dependency potential. However, it is not a serious issue for terminal cancer patients. In any case, the use of drugs should be tailored according to different cancer types and clinical conditions. Various drug uses in different cancer types and clinical conditions are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. 3. Drug interactions with anticancer agents Studies on the drug interaction between antidepressants and anticancer drugs are still limited. However, there are some remarkable findings. Firstly, corticosteroid is known to have possible side effects on mood and cognition. It usually occurs during the first few weeks of treatment and is dose-dependent.26 Secondly , co - administration of tamoxifen and paroxetine, sertraline or venlafaxine, which are CYP2D6 enzyme inhibitors, can reduce the therapeutic effect of tamoxifen. Currently, citalopram is recommended as the choice of antidepressant for breast cancer patients on tamoxifen.20 Thirdly, antidepressants (e.g. SSRIs and SNRI), analgesics (e.g. tramadol, opioids) and antiemetics (e.g. ondansetron and granisetron) may act synergistically and result in the development of the serotonin syndrome.27 Its clinical presentation includes autonomic dysfunction (hyperthermia, tachycardia, hyper/hypotension, sweating), gastrointestinal upset (nausea, diarrhoea), neuromuscular (hyperreflexia, myoclonus, tremor, including shivering) and psychiatric symptoms (confusion, agitation, coma). 4. Antidepressants as adjuvant therapy for other symptoms in cancer patients A series of studies28-35 have demonstrated the use of antidepressants as adjuvant therapy for pain, hot flashes, pruritus, nausea and fatigue in cancer patients (Table 5). Psychosocial Treatment Several meta-analyses have demonstrated the effectiveness of psychotherapy in treating depression in cancer patients.36-38 In the early stage of the disease, individually-focused psychotherapies include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), problem solving therapy, psychoeducational interventions, relaxation therapies, behavioral activation and interpersonal therapy. As the disease progresses, systemic psychotherapies such as couple therapy, group therapy, and family therapy may offer additional benefit. In advanced stages, interventions to promote active coping strategies (such as relaxation therapy, biofeedback, guided imagery and hypnosis, CBT and problem-solving therapy) and supportive-expressive, narrative and existential therapies (such as dignity therapy and CALM – Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully therapy) are shown to be effective.39-42 There is lack of evidence to show which particular type of psychotherapy is more effective. Therefore it may be wise to choose the type that is tailored to the patients’ needs. Cancer and suicide The incidence of suicide in patients with cancer is almost doubled that of the general population.43 Risk factors for suicide can be categorized into general or cancer-specific. Advanced age, male gender, occupation that allows easy access to lethal methods of suicide, few social supports, family history of suicide, past or current psychiatric illness, past suicidal attempts, history of substance or alcohol abuse, sense of hopelessness, recent loss of a friend or a spouse and media effect are general risk factors for suicide. Among them, depression and hopelessness are two major factors in predicting patients for suicide.44 Cancer specific risk factors include cancer types (lung, stomach, oral, pharyngeal and laryngeal cancers)43, advanced stage at diagnosis, persistent pain and delirium.45 Protective factors for suicide include unfinished responsibilities in life, good social support, effective care for physical and mental problems, restricted access to lethal methods of suicide, good coping and problem solving skills, as well as cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide. Depression in carers Studies have shown that carers for cancer patients are at risk of emotional distress and depression. Carers who are advanced in age, female, of spousal relationship with patient, with poor health or has a past history of psychiatric illness are more likely to suffer from depression.46 In particular, being very attached to and fear of losing the spouse are at greatest risk.47 Therefore, clinicians should also pay attention to the psychological wellbeing of carers of cancer patients. Conclusions Sadness is a normal reaction to the diagnosis of cancer but clinical depression is a serious psychiatric condition which can have multiple adverse impacts. It is of paramount importance for physicians to be aware of and to look for depression in cancer patients. Recently screening tools have been validated which may be of help in identifying the condition. Both pharmacological and psycho-social treatments currently available are effective in treating depressed cancer patients. Timely referral to psychiatrists or other mental health professionals should be considered when the clinical situation becomes more complex.

Yin-ying Ma, MBChB (CUHK), MRCPsych (UK), FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry) Ki-yan Mak, MBBS (HK), MD (HK), FRCPsych (UK), FHKAM (Psychiatry) Correspondence to: Dr Ma Yin Ying, Room 704, Alliance Building, 130 Connaught References

|

|