March 2012, Volume 34, No. 1 |

Original Articles

|

Prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus seen in New Territories East primary care clinicsMaria KW Leung 梁堃華, Cheung Yu 張宇, Eric MT Hui 許明通, Kenny Kung 龔敬樂, Samuel YS Wong 黃仰山, Augustine Lam 林璨, Philip KT Li 李錦滔 HK Pract 2012;34:17-24 Summary Objective: To identify and compare the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus with those without hypertension and diabetes. To assess the association of depressive & anxiety symptoms with the control of hypertension and diabetes in hypertensive and diabetic patients. Design: cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Subjects: Patients over the age of 18 years old from the electronic patients’ records, with a documented history of hypertension or diabetes mellitus, were recruited from three GOPCs. Those ≥ 18 years without any chronic illnesses were recruited as the control group. Main outcome measures: 1) Prevalence of anxiety or depressive symptoms in patients with or without hypertension or diabetes. 2) Comparison of anxiety and depression scores between non-hypertensive/ non-diabetic and hypertensive/diabetic groups . 3) Correlation between A score, D score, blood pressure readings and HbA1c. Results: 1059 questionnaires were collected and the response rate was 91.5%. 20.6% of hypertensive only patients had an A-score (anxiety) >8 and 33.8% had D-score (depression) >8. 20.6% of diabetic patients had A-score > 8 and 30.8% have D-score >8. 29.8% of non-chronic illness patients had an A-score >8 and 33.5% had D-score >8. There was no significant difference between A-scores and D-scores among those with or without chronic illnesses. There was also no correlation between A score, D score, SBP, DBP, and HbA1c. Conclusion: This study demonstrated the high prevalence rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms in both groups of patients with or without chronic illness or illnesses and attention should be put on mental health promotion for both groups. Keywords: Depression, anxiety, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hospital anxiety and depression scale 摘要 目的:確定高血壓和糖尿病患者的抑鬱與焦慮症狀患病率,並與無高血壓和糖尿病的病人進行比較。評估抑鬱和焦慮症狀與高血壓及糖尿病控制之間的關聯。 設計:橫斷面問卷調查對象:從三所綜合門診診所的電子病歷記錄,徵募18歲以上而有高血壓或糖尿病史的病人,另以18歲及以上而非慢性病者作為對照組別。 主要測量內容:1. 高血壓或糖尿病患者和非患者的焦慮或抑鬱症狀患病率。2. 比較高血壓或糖尿病組別與非高血壓或非糖尿病組別的焦慮和抑鬱評分。 3. 焦慮(A)評分值、抑鬱(D)評分值,血壓值和HbA1c水平之間的關聯。結果:共收回1059份問卷,應答率為91.5%。在僅有高血壓患者中,20.6%的A評分值 >8,33.8%的D評分值 >8。在糖尿病患者中,20.6%的A評分值 >8,30.8%的D評分值 >8。在非慢性病患者中,29.8%的A評分值 >8,33.5%的D評分值 >8。在慢性病患者和非慢性病患者組別之間,A評分值和D評分值無顯著差異。A評分值、D評分值、SBP、DBP和HbA1c水平之間亦無關聯。 結論:本研究結果顯示慢性病患者和非慢性病患者均有高的抑鬱及焦慮症狀患病率。因此,應注視提升他們的精神健康狀況。 主要詞彙:抑鬱,焦慮,高血壓,糖尿病,醫院焦慮及抑鬱量表 Introduction With our elderly population growing in number in our society, the number of people having chronic illnesses will also increase. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus are the two most common chronic diseases seen in the general outpatient clinics of the New Territories East Cluster (NTEC). Annually about 74000 hypertensive patients and 28000 diabetic patients attend the general outpatient clinics (GOPCs) in the Hospital Authority’s (HA) New Territories East Cluster for management. Many studies have tried to elaborate on the relationship between chronic illness and psychiatric disorders. A local study on the elderly Hong Kong population found that the prevalence of depression rose markedly with the number of chronic medical conditions.1 Some overseas studies2-5 also reported that anxiety and depressive disorders are more prevalent in adults with diabetes mellitus than in the general population. One meta-analysis from the USA has shown that anxiety disorders are associated with hyperglycaemia in diabetic patients.6 Despite several review papers7-9 showing negative findings in the association between hypertension and depression, some studies10-12 have found support for the existence of such an association. Overall, the association between hypertension or diabetes mellitus and symptoms of depression and anxiety remains unclear. As poor mental health could be associated with poor control of hypertension or diabetes mellitus, it is important to find out the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus in order to plan for better management. As there is a lack of local data on this topic, the current study was carried out in NTEC GOPCs to help delineate the relationships between mood symptoms and hypertension or diabetes in Hong Kong. Hypothesis and Aims We hypothesized that hypertensive or diabeticpatients would have a higher anxiety or depressivescores than those patients without chronic illnesses. The aims of this study were:

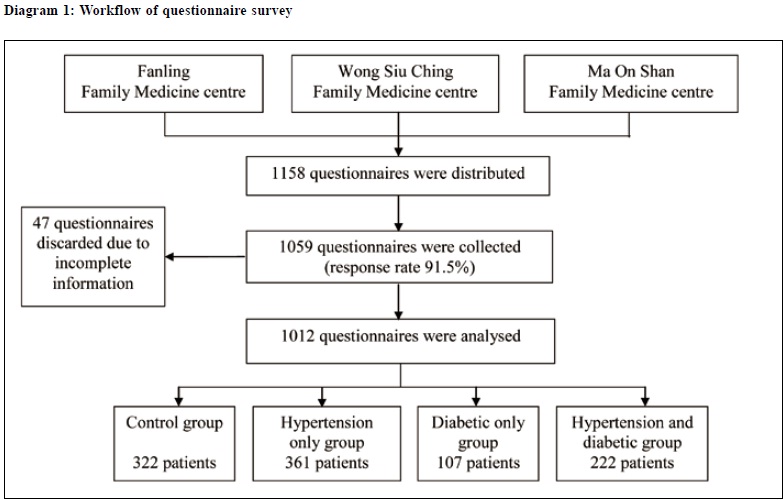

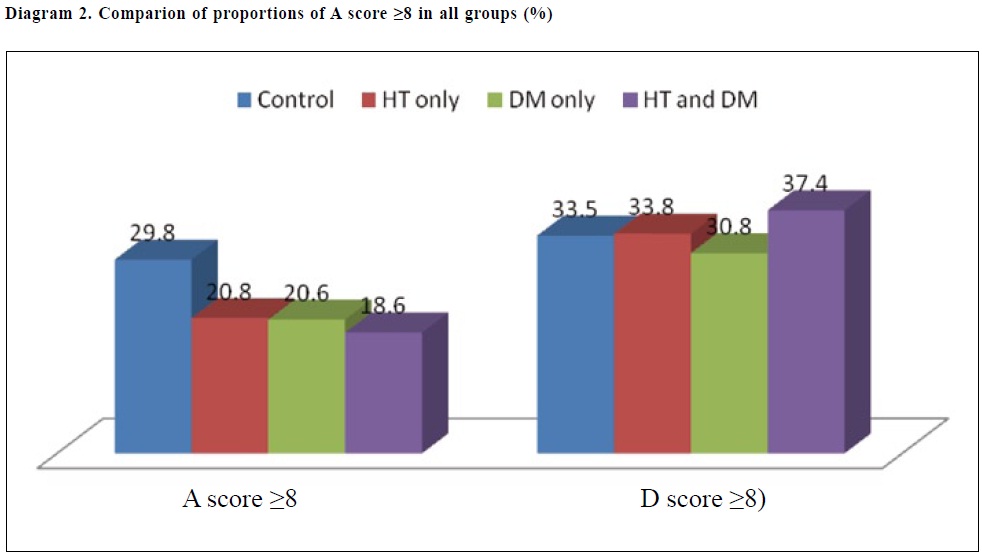

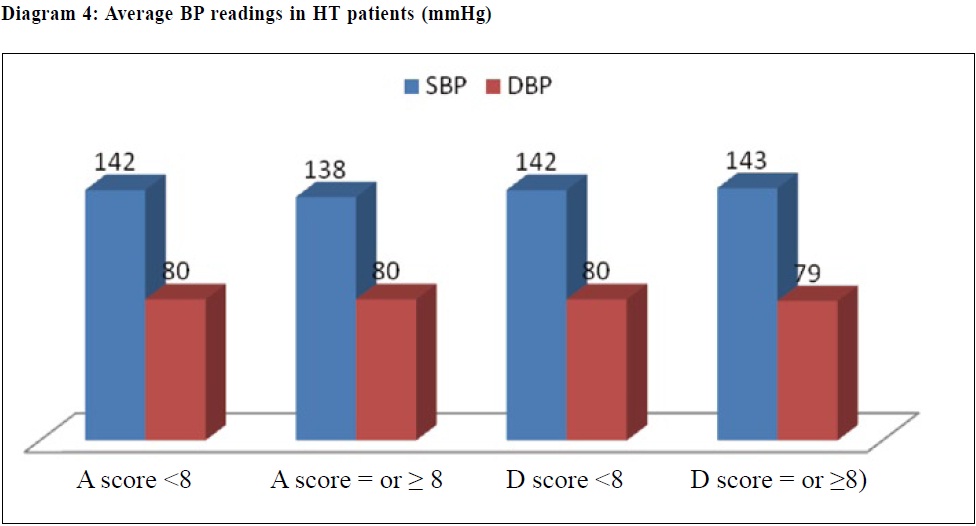

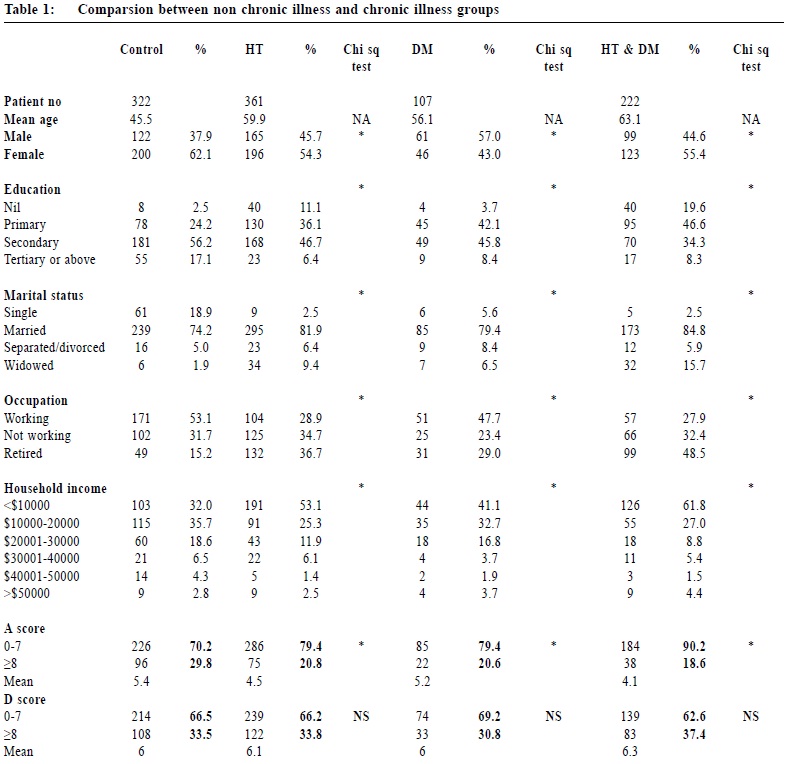

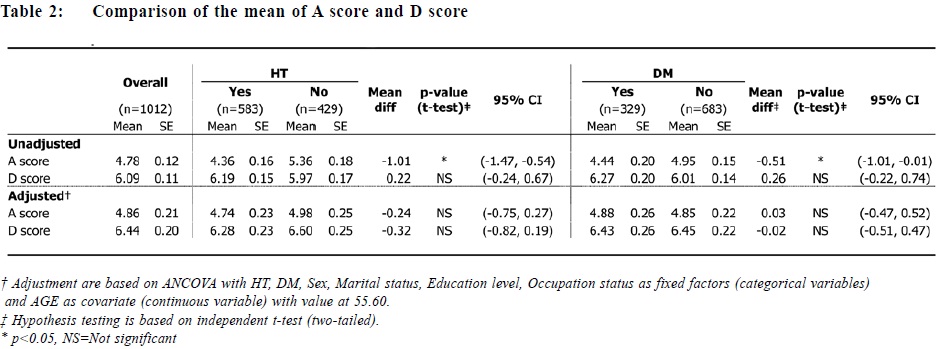

Method Study design and patient recruitment This was a questionnaire survey. All patients aged ≥ 18 years old attending three family medicine clinics (FMCs): the Fanling Family Medicine Clinic (FMC), Tai Po Wong Siu Ching FMC and Ma On Shan FMC from 1st December 2008 to 1st February 2009 were invited to participate in the study until the targeted sample size was reached. These three FMCs are GOPCs accredited as family medicine training centres, providing around 300,000 appointments for the general public within their locality each year. Those without any chronic illness were recruited into the control group, while those with a documented history of hypertension or diabetes mellitus from electronic patient records, regardless of where they were followed-up, were recruited as the chronic illness group. Patients were then divided into four groups, namely the control group, hypertensive only group, diabetic only group and both hypertension and diabetic group. Questionnaires were distributed to eligible patients at the waiting hall before their consultations. Written consent was obtained from invited patients before questionnaire completion. Healthcare assistants were available to help those who were illiterate. Questionnaire distribution continued until the estimated required number of questionnaires (please see below) had all been distributed. Patients had to hand in the questionnaires to the doctors during the consultation so that the attending doctors could complete the questionnaire section regarding the presence of chronic illness and their latest blood pressure and/or HbA1c readings. As each questionnaire was allocated a number, the response rate could be calculated after the collection of questionnaires. The questionnaire design included three parts: 1) demographic data including age, sex, marital status, education level, other co-existing co-morbidities and occupation status; 2) validated Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)13; 3) presence of diabetes mellitus or hypertension according to documentation from electronic patients’ records and their latest control (i.e. latest HbA1c and blood pressure readings within last 6 months as noted from electronic patients’ records). The Chinese version of the HADS had been shown to have good reliability and validity.14,15 A study in 1995 had validated the Chinese version of the HADS: and sensitivity was 79% and specificity was 80%.16 It was also independent of the subject’s educational level and was simple to use. Approval for using the Chinese version of the HADS had been obtained from the GL Assessment, UK. Outcome measures HADS consists of 14 items, 7 for anxiety (HADS-A) and 7 for depression (HADS-D). Each item is rated from 0 to 3, and the sum score range on the HADS-A and HADS-D, therefore, is from 0 to 21. Based on an accepted cut-off level on HADS17, prevalence of clinically relevant anxiety or depressive symptoms in patients was identified. Presence of clinically relevant anxiety symptoms was confirmed when anxiety score was ≥ 8. Presence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms was confirmed when depressive score was ≥ 8. Data were analyzed using Excel. Comparison of characteristics of patients was done by chi squared test. Relationships between anxiety/depression scores and other factors (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and demographics) were analysed using ANCOVA. Correlation between A score, D score, blood pressure readings, and HbA1c was also measured by Pearson’s correlation. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Sample Size calculation18-20: Taking a statistical power of 90% and a two sided significance criterion of 0.05, 337 subjects were required from each study site, i.e. 1011 in total. Results Patients’ characteristics (Diagram 1 and Table 1) Overall, 1158 questionnaires were distributed. 1059 questionnaires were collected and the response rate was 91.5%. There were 361 patients with hypertension only, 107 with diabetes mellitus only, and 222 with both hypertension and diabetes mellitus. The control group had 322 patients. There were significant differences between chronic illness groups and non-chronic illness group in terms of their mean age, sex, marital, education and occupation status, as well as household income. Chronic illness patients were older, with lower education, widowed, retired or not working. As these demographic characteristics contributed significantly to the results in differences between A and D scores, data were further analysed with adjustment of age, sex, occupation status, marital status and education level. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms (Diagram 2) The prevalence rate of anxiety symptoms in the control group was 29.8%, which was significantly higher than the chronic illness groups (hypertension only group: 20.8%; diabetic only group: 20.6%; both hypertension and diabetic group: 18.6%). The combined hypertension and diabetic group had the highest prevalence rate for depressive symptoms, but there was no statistically difference among all 3 groups. Comparison of A and D score between non -hypertension and hypertensive patients, and between non-diabetic and diabetic patients (Table 2) Both non-hypertensive and non-diabetic patients had an initial higher A scores than hypertensive and diabetic patients. After adjustment with demographic characteristics, the study found no significant difference in A and D score between non-hypertension and hypertensive patients, and between non-diabetic and diabetic patients. Correlation between A score, D score, HbA1c, and BP readings (Diagrams 3&4) In diabetic patients, the differences, in their average HbA1c readings between A score < 8 and ≥ 8, and between D score < 8 and ≥ 8, was 0.3% and 0.4% respectively. In hypertensive patients, the average systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) readings were similar regardless of their A and D scores. Our study found no correlation between A score, D score, SBP, DBP and HbA1c readings. Discussion The main aim of our study was to find out the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in hypertensive and/or diabetic patients as compared to those without these chronic illnesses. In this study, the prevalence rates of anxiety and depressive symptoms in the non-chronic illness group were both higher than those in the chronic illness groups. This could be related to their social factors. The non-chronic illness group was younger and had a higher proportion of working class. Work stress could have significant impact on their emotional status. In addition, most of the patients in the nonchronic illness group had relatively lower household income compared to the average household income in 2009.21 Financial burden might further increase their emotional stress. Those without chronic illness represent a group of people who may not require any regular follow up at general outpatient clinics. The difficulties in gaining access to government medical care will inevitably worsen their stress level. Due to a higher stress level among non-chronic illness group, the effect of hypertension or diabetes on mood symptoms could be overshadowed in the chronic illness groups. Although previous overseas studies suggested behavioural mechanism as a link between depression and hypertension as depressed individuals might have unhealthy lifestyle behaviours and poor compliance with treatments22,23, our study found no association between hypertension and depressive or anxiety symptoms after adjustment for age. There was also no correlation between blood pressure control, depressive and anxiety symptoms. This was similar to the results of some overseas studies,24-26 including the CARDIA study, which did not find any independent association between depression or anxiety and 10-year incidence of hypertension.27 This could be explained by the fact that hypertensive patients in our study had generally stable control as reflected by their near normal blood pressure readings. This is the same for the diabetic patients in our study whose HbA1c readings were near optimal. This has reflected that stable hypertension and diabetes mellitus may not have affected their mood significantly. It would be interesting to further explore the impact of complications from hypertension and diabetes mellitus on their mood symptoms. However, this cross-sectional study has still uncovered a large proportion of hypertensive and diabetic patients having mental health problems. Further prospective studies might look into the progression of chronic illnesses and, with more sensitive assessment tools, should be carried out to help elaborate the relationships between chronic illness and depression and/or anxiety. Limitations Firstly, the questionnaire was designed to detect clinically anxious and depressive symptoms only and not for the diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorders. As formal psychiatric interviews were not carried out in our clinical setting, the prevalence rates of depression or anxiety symptoms in these patients may be overestimated. Secondly, the high response rate could be attributed to selection bias. Patients who declined to fill in the questionnaires were excluded from the study. Thirdly, the questionnaire survey was carried out only in three clinics in New Territories East Cluster. Generalizability was therefore limited and sampling bias might affect the results of our study. Future studies in the general population rather than in the outpatient clinics should be considered. Conclusion Our study found that depressive symptoms were common in both the chronic and non-chronic illness groups, whereas anxiety symptoms were even more prevalent in the non-chronic illness patients. Social factors seem to have more significant impact on mental health than hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Further prospective studies with more sensitive tools should be carried out to elaborate on the relationship between chronic illness depression and/or anxiety. Nevertheless, emphasis on mental health promotion should be put on both the non-chronic illness and chronic illness groups.

Maria KW Leung, MRCGP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Cheung Yu, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Eric MT Hui, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Kung Kenny, MRCGP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Augustine Lam, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Fam Med) Samuel YS Wong, MD, FRACGP Philip KT Li, MD, FRCP (Lond & Edin) Correspondence to: Dr Maria KW Leung, Fanling Family Medicine Centre, 1/F, 2 Pik Fung Road, Fanling, NT, Hong Kong SAR References

|

|