|

December 2013, Volume 35, No. 4

|

Discussion Paper

|

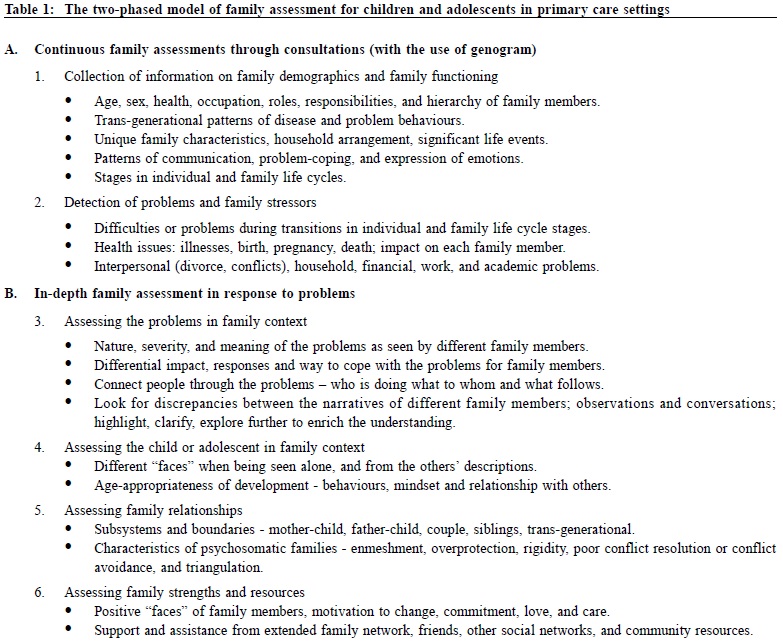

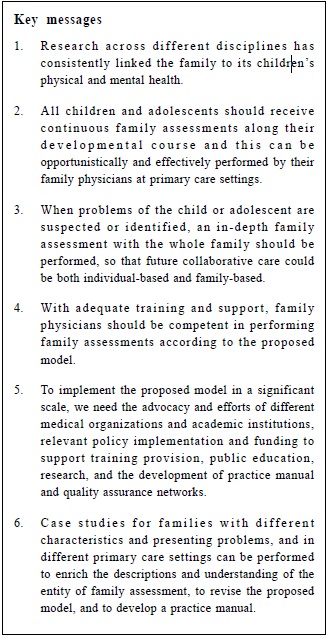

Primary care assessment of family for children and adolescentsEdmund WW Lam 林永和 HK Pract 2013;35:120-127 Summary Trained family physicians can provide assessment of family for children and adolescents to address their health needs at individual and family levels opportunistically and effectively. Illustrating with an actual case, a two-phased model of primary care family assessment with six key assessment areas is outlined: (i) collecting background family information, (ii) detection of problems and family stressors, (iii) assessing the problems in the family context, (iv) assessing the child or adolescent in the family context, (v) assessing familyrelationships, and (vi) assessing family strengths and resources. Feasibility and practical aspect are discussed so as to widely implement this model in Hong Kong. 摘要 家庭醫生在培訓後可合適而有效地為兒童和青少年的健康需要在個人和家庭層面提供綜合家庭評估。本文以一則個案為例,概述在六個主要領域,以兩階段模式進行基層家庭評估。這六個領域分別為:收集家庭背景資料,適時發現問題及家庭承受壓力源,評估家庭中存在的問題,按家庭因素評估該兒童,評估家庭成員間關係,評估家庭的潛能和資源。最後,廣泛地討論在香港實施這模式的可行性和實用性。 Introduction While advances in technology and knowledge have improved our health standards and quality of life in general, the prevalence of chronic health problems among children and adolescents is actually increasing both locally and worldwide, especially in emotional, behavioural and developmental difficulties.1-5 Taking into account the rapidly changing cultural, educational, socio-economic, political, and ecological contexts, health issues of Hong Kong children and adolescents have never been so complex and diversified. Although we can do very little about nature, we can certainly make some adjustments in nurturing our children and upbringing our adolescents, and this brings us to the importance of family. To date, researches across different disciplines have consistently linked the family to children's physical and mental health and adolescents' development.6-8 Ideally, all children and adolescents should receive continuous attention in their growing up period and family assessments along their developmental course. When problems or stressors are suspected or identified, an in-depth family assessment should be performed, so that any future treatment would not only be on an individual-basis but also familybased, such as considering family therapy that is now widely known to be effective in solving childhood and adolescent problems.9,10 This paper aims to discuss a model for family assessment that may be widely practised by trained family physicians in Hong Kong. The family of Andy*

Andy is a 13-year-old Chinese boy and his parents, Maria and Boris, are both in

their 50s. Since Andy's birth, he had been seeing Dr R who was the family's doctor

for all ailments and sickness and they never consulted any other doctors. *For the

sake of confidentiality, the names above and some background information of the

family have been modified. Continuous family assessments through consultations During the frequent clinical encounters, Dr R had had multiple opportunities to establish a good doctor-patient-family relationship, to collect and record the family demographic data with the use of the genogram, and perform family assessments. Maria was an Indonesia-born Chinese who came to Hong Kong when she was 24. She stopped working after marriage. She had no chronic illnesses and seldom consulted Dr R. Boris was a Hong Kong Chinese who worked as a quality assurance manager in Shenzhen from Mondays to Fridays. He consulted Dr R quite often, mostly for minor ailments and for follow up of his Hepatitis B carrier state. In 2005, he had a heart attack and fortunately he recovered uneventfully after angioplasty. During weekdays, Maria had to take care of Andy alone in Hong Kong, and Andy's family structure resembled that of a "single-parent family". Maria had expressed parenting difficulties at Andy's consultations on several times and Dr R provided support and advice to her accordingly. At stressful times, such as during Andy's adjustment to kindergarten and Boris's heart attack, Dr R also tried to help the family to cope. After Andy's entry to primary one, the family consulted Dr R less frequently and seemed to function better. In December, 2012 Andy developed an eczema exacerbation and Boris brought him to consult Dr R. In order to assess bio-psychosocially, Dr R directed the interview to the topic of stress. Boris expressed that Andy experienced stress in many areas and that Andy had become very emotional and irritable lately, in particular towards his mother. Andy also became obsessive with cleanliness and spent hours bathing and washed hands almost forty times daily. His academic performance also deteriorated drastically. Help from the school social worker and teachers were solicited but it made little difference. Boris also mentioned that Maria might be having depression and she was easily irritated by the son. Maria had received individual counselling for control of her emotion and her temper from an Integrated Family Services Centre, but her condition waxed and waned. Andy's presentation was compatible with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Furthermore, based on Boris's description of the conflictual relationship between Maria and Andy and the clustering of symptoms during conflicts, Dr R proposed an in-depth family assessment with the whole family, to understand Andy's problems, and also as a ticket of entry to assess Maria's apparent depression. Boris agreed.

In-depth family assessment A 45-minute extended session was arranged. The involved social worker and teachers were liaised. Right from the start, by observing their seating positions, and noting Maria and Andy sitting very close to each other and Boris at the far end, one could already picture their relationships. Some important dialogues of the session were transcribed, using the abbreviations:

W for wife;

To navigate along the session, four core assessment areas were elaborated sequentially: A) Assessing the problems in the family context As it was Andy's problems which brought the family to seek help, it would be more acceptable and easier to start from there: Dr: Maria, how do you see Andy's problems? This question looked like centering at the presenting problems, but by directing it to Maria, it could be an attempt to bridge into the interpersonal dimension. Maria claimed that Andy was lazy, irresponsible, and emotional, as a result of having been spoiled. She disliked giving Andy a psychiatric diagnosis, while accepting that she herself probably had depression, and it was triggered by Andy's problems. The word ‘spoiled" had a relational meaning and was explored. Then, the story about how hard Maria had been taking care of Andy over these days was narrated. Andy was noted to be attentive to every word from Maria. He burst into tears when Maria started sobbing. Boris looked sad, gazed down and remained silent while listening. All these observations were registered for making deductions. B) Assessing Andy in the family context Andy was described as a bad boy previously. However, in the session, he appeared very caring for Maria. When Maria cried, he was the one to comfort her, instead of Boris. This observed discrepancy could be used for further exploration: Dr: Just now, I notice that Andy is a very good boy who cares so much about mom's feelings. He really doesn't look like someone who is so disobedient and shouts at parents? Can you tell me more about that? This question highlighted a different "face" of Andy, so that the family could reflect, re-think, and a different story about Andy might be co-created. Another essential area of exploration was about Andy's development in the relationship context. From the parents' narratives, Andy had many immature and undesirable behaviours which made them unhappy, such as demanding Maria to wake him up for school and to pack schoolbag for him. By exploring through linking these behaviours with age, a different level of interchange might be reached:

Dr: Andy, can you stand up for a while? Asking the child to stand up could introduce novelty and fun to the session and highlight the age-development discrepancy. The above dialogues not only created a topic to discuss how the parents perceived Andy's "developmental delay", but also opened the door to assess the threesome's relationships. Since Maria claimed that Andy had forced her to treat him like a very young kid for years, did Boris maintain it? At suitable moment, Boris by shifting the exploration to himself expressed hesitatingly that he simply could not help the situation, even though he knew this could hinder Andy's developmental progress. It then went on to explore what/who had prevented him to do so. C) Assessing family relationships When Boris was asked about Andy's problem, he mentioned that Andy had spent over an hour in the toilet every night. Andy explained that he was staying there to contemplate. Then a sequence of questions was used to explore family relationships:

Dr: Andy, can you tell me what you were thinking about in the toilet? When Andy tried to reply, Maria jumped in to answer, and Andy allowed this to happen. Boris never reacted this way. This dynamic was registered and questions on the mother-son closeness were followed:

Dr: Your mother seemed to know all the things you were thinking

privately there. How did she know? Changing seats gave Andy a stage to express what he could not make parents understand. But, for some reason, Andy did not use the chance. Therefore, Dr. R shifted to try entering the father-son relationship:

Dr: Did your dad also memorize things for you? As the session went on, it became clear that Maria and Andy had been emotionally over-connected for years, while Boris and Maria had had intense but suppressed conflicts. Though Maria complained Boris of being irresponsible and neglecting her since Andy's birth, Boris also expressed that the mother-child dyad rejecting him all the time. Andy finally could voice out his longstanding worry about the parents' marriage. From this perspective, Andy's problems and the undesirable, younger-than-age behaviours were shown to be closely linked to Maria's emotional outpouring and the sense of abandonment by Boris, Boris's helplessness and detachment, and the tension between the couple's passive-aggressiveness. D) Assessing family strengths and resources The assessment process facilitated the family to use new perspectives to look at themselves and their problems. The hidden intra-familial and extra-familial strengths and resources were assessed and gradually uncovered. In the session, Andy appeared as a caring and mature son rather than a psychiatric patient. Boris was not that selfish and unaffectionate, and he wanted to be more intimate with Maria and Andy, and to do more for the family. Maria could also be very rational and calm, though being seen as a depressed menopausal woman. They were actually very caring of each other. It was so encouraging to see them all agree to work on improving family relationships. A management plan collaborating with mental health professionals, social worker, and teachers was formulated. Hope was rediscovered. The proposed model for primary care family assessment Without proper family assessment, the treatment for Andy's problems might only include medications and/or individual psychotherapy. Maria and Boris might also receive similar individual-based treatments. The links between their problems and the opportunity to open the doorway to change the interlocking family milieu would be missed. Fortunately, timely family assessment addressing the broad needs of the family was performed. The findings could be communicated to medical, social, and educational professionals, and management would attend to the whole family as well. This highlighted the importance of devising a suitable model of family assessment for children and adolescents in primary care. Discussion A two-phased assessment model (Table 1) was designed with reference to Andy's case and some existing assessment models.11-15

Good doctor - patient - family relationship is the key to make our model work, and this can be achieved by different ways, depending on the doctor's personal characteristics, commitment to people, and communication skills. During consultations, questions like "How is everyone at home?" "How come it is you (husband) but not your wife to accompany your son to see me? Is there anything that has happened to your wife?" can already probe for family information while building rapport. With time, pieces of family information are accumulated. Genogram, combining both the biomedical and psychosocial information of the family, can serve well as an excellent database for future reference.12 Sometimes, there are contradictory messages from individual members and proper explorations are required, which may further enrich the understanding of the complexity of the family. A family is usually more willing to present hidden problems to its entrusted doctor. A doctor who knows the family well also has a higher chance of detecting distresses in the family. In response to stressors and problems, an in-depth family assessment should be performed, making reference to past database. While preliminary hypotheses can be formed from interviewing individual members, it is recommended to invite the whole family to come for assessment.16 From the author's experience, families usually would agree to come together if they can understand the importance of the session and that the assessment is centred at family. Referring to Table 1, one can gain a better understanding about how to ask questions, how to respond to the answers from different individuals, how to observe and make use of the family dynamics, and how to construct the assessment in Andy's session. By using interpersonal questions, "What is your explanation of his symptoms?" "How does his problem affect you?" "How do you cope when he behaves so?" one may connect the narratives of different members in the relational context of the presenting problems. New stories may come out, so also new "faces" of individuals. For Andy's family, the assessment helped the whole family to understand how they got stuck in their relationship with each other. It also helped them to gain insights to what they should change and what hidden family resources they can use. With the proper balance of individual-based and family-based treatment, the threesome is now making good progress Feasibility and practical aspects to implement the model in Hong Kong Time constraint is always a concern in busy clinics. Yet, family-oriented clinic consultations were found to take only a few minutes longer than usual consultations.17 Session of 16 minutes was found to be adequate for residents in family practice to record family demographic information on a genogram.18 The beauty of this model is the ability to utilise the assessment opportunities obtained at multiple consultations. For the in-depth family assessment, scheduling a 45-minute extended session is recommended, and this requires the adoption of a flexible appointment system. Video-recording should be considered so that the essence of the session can be captured for data analysis, but the family's consent must be sought. A recent study found that 62.5% of Hong Kong's general population had regular family physicians, and an average person consulted his/her family physician eight times annually.19 Family physician, as the point of first contact to families, can opportunistically provide family assessments in their practices and act accordingly, as the "gatekeeper" of the healthcare system. By including paediatricians, and other various specialists who are practising as family physicians, the number of practising family physicians in Hong Kong is approaching 6,500. If they can be empowered to practise this model, the positive impacts on our future generations should not be under-estimated. To implement this model in a significant scale, the followings should be addressed: 1) Competency and training Through various postgraduate training courses and the vocational training programme for family physicians, it is estimated that about 2,000 local family physicians had received trainings in "Working with families". By providing didactic workshops on family assessments, they can become the pilot group to try this model in their practice settings. Further training can also be supported by the Academy of Family Therapy (www.acafamilytherapy.org), formerly established as the Hong Kong University Family Institute, which offers a broad range of training programmes and live demonstrations of family interviews. 2) Funding and policy making Certainly many family physicians are willing to spend extra time and efforts to learn and to perform family assessments, for the best interests of their patients. However, to motivate a significant proportion of family physicians to provide new services in their practices, financial incentives from the government are pertinent.20 It is encouraging to see that the newly released Hong Kong Reference Framework for Preventive Care for Children in Primary Care Settings emphasizes the importance of family relationships.21 In reality, we need the advocacy and efforts of different medical organizations and academic institutions, relevant policy implementation and funding to support the dissemination of this model via training provision, public education, research, and development of practice manual and quality assurance networks. 3) Future research Case studies performed on families with different characteristics and presenting problems, and in different primary care settings can enrich the descriptions and understanding of the entity of family assessment, so as to revise the model and to prepare the practice manual. Families being assessed can be recruited for focus group study, so are the involved family physicians.

Conclusions All children and adolescents in Hong Kong deserve to have continuous family assessments along their developmental course to promote their family health, and to receive an in-depth family assessment at times when problems arise, so that the family perspective of treatment can complement the individual-based treatment. Family physicians, as the point of first contact to families, can efficiently provide family assessments in their practices. Government funding, relevant policy implementation, adequate training, and on-going professional support are required to promote and empower more family physicians to use this assessment model and to contribute to bettering the child, adolescent and family health in a societal level.

Edmund WW Lam, FHKCFP, FRACGP, PDipComPsychMed (HKU), MSocSc(Marriage and

Family Therapy) (HKU)

Family Physician in Private Practice

Correspondence to : Dr Lam Wing Wo's Medical Practce, G/F 125, Belcher's

Street, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong SAR. Email: alfredtang@hkma.org

References

|

|