|

December 2013, Volume 35, No. 4

|

Dr Sun Yat Sen Oration

|

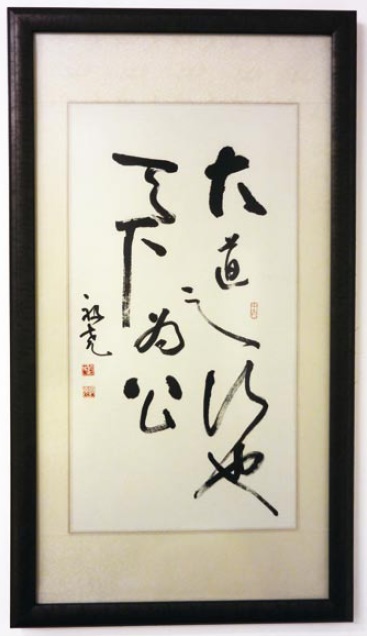

The lost art of medicine in the 21st century?Joseph JY Sung 沈祖堯 HK Pract 2013;35:128-130

It is indeed a great honour bestowed upon me to give this prestigious lecture named after our national hero, Dr. Sun Yat-sen: a doctor, a revolutionist, a self-less giver. In his famous motto, he reminded us that in our life, we should focus on benefiting the bigger self, the community. When I was an intern and a junior fellow in public hospital, my mentors taught me that as a doctor, we need to be there as long as our patients need us. We need to practise medicine with not just knowledge and skills, but also with passion. Our teachers taught us, not in words, but in their life. They exemplified what they taught, in their whole career. In recent years, reports from UK, US and Australia revealed that there were increasing number of junior doctors leaving the clinical career because they resented the lifestyle, resented the working condition and they lost interest in a career that they strived so hard to get in. In the UK and Europe, unions fight for shortest possible work hours, highlighting that resident fatigue is a serious patient safety issue. Back home, I hear that today, the ROAD to success in medicine is to choose Radiology, Ophthalmology, Anaesthesiology and Dermatology. Not that I have any prejudice against these specialties. These are very important streams in clinical medicine. But are we choosing these specialties as our future career, not for the interest or scientific advancement, but for the "quality of life" that they may bring about? Are we more concerned about the remuneration, how fast we can ascend the career ladder, how quick we can obtain professional autonomy? When did we start to forget the passion we had when we chose medicine as our career? The fundamental problem in our healthcare system is a lack of meaning. It is ironic that while we have all the means of managing a diseased organ or body system, we have lost the meaning of taking care of a person with sickness. We have lost the meaning of our sacred duty because it lost the totality. We are merely part of a big machinery, like a worker doing a small part in the assembly line, and the machinery is called general hospital, polyclinic, or whatever fancy name we call it. In this machinery, medical decision-making is no longer a personalised consideration. Workers (doctors, nurses, therapists and administers) are burdened by time-consuming paper work. Care providers are fear of malpractice litigation. Financial disincentives threaten clinical livelihood and innovation. Humanistic, relationship-centered attitudes and caring behaviour do not necessarily find their way into the clinic and the hospital floor. Gradually, physicians call themselves "providers" or "vendors" and patients regard themselves as "consumers" or even "customers". The doctor-patient relationship has eroded into one of business engagement. That is a detrimental change in our care model. In the end, physicians, nurses, allied health workers find themselves frustrated and demoralised by a work environment devoid of respect and compassion for its employees. Around the world, healthcare workers, emotionally exhausted and burned out, leave practice of medicine in an unprecedented numbers.

Recently, we see light at the end of tunnel. In 2003, when SARS hit Hong Kong, it was a moment of truth for many. Doctors, nurses and patients paused to think about the meaning of life and death. A final year medical student contracted SARS while studying in the medical ward and came down with fever and shortness of breath. In his six-week hospitalisation, he learned something that we could not teach in lectures and tutorials: the true meaning of professionalism. When he recovered and before he left hospital, he wrote, "When I fell down with fever, I was upset… Then by observing what you and others did, I found it extremely enlightening. I believe that I begin to know the true meaning of medicine. What I've learned in the past weeks is far more important than what I've learned in the 5 years of medical curriculum." A surgeon had similar experience when he became a SARS patient. He wrote in a scientific journal the following words, "I felt really glad and grateful, not only because I survived, but because I suddenly started to appreciate many "small things" in life. From being a healthcare provider to becoming someone at the receiving end, such a sudden and dramatic role change generated an impact greater than I could ever image…" From becoming a patient ourselves, we start to pick up the importance of humanity in medicine again.

The losing art of medicine is a result of losing humanistic nature of medicine.

The loss of humanity in medicine is a result of automation of medical technology,

compartmentalisation of medical specialties, and perhaps the over-emphasis on efficiency

and cost-effectiveness. Mindful, dignified and collaborative healthcare requires

time – the time to listen, to touch and to create meaningful relationship with the

patient. But we seem to forget about this. Neuwirth's words hit the nail right on the head, "One of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century is that in developing the means, we have forgotten the meanings". "Practice of medicine is primarily a humanistic endeavour, not a scientific one". We all know only too well that when the cure of a disease is not possible, as is so often the case, the humanistic care of patient and family fosters hope and healing. Therefore, on this tipping point of our healthcare system, I urge every member of our profession to devote our time, our knowledge and our energy to serving others with our heart and our soul. And devote yourself to creating something that gives you purpose and meaning in your life. *This paper was presented at the 24th Dr Sun Yat Sen Oration on 15 June, 2013.

Joseph JY Sung, MD, PhD

Vice-Chancellor The Chinese University of Hong Kong Correspondence to : Professor Joseph JY Sung, Vice-Chancellor and President's Office, Room 101, 1/F, University Administration Building, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR. |

|