|

June 2013, Volume 35, No. 2

|

Original Articles

|

Barriers facing family physicians providing palliative care service in Hong Kong – A questionnaire surveyTin-chak Hong 康天澤,Tai-pong Lam 林大邦,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2013;35:36-51 Summary

Objective: To investigate willingness and barriers for family physicians

to provide palliative care service in Hong Kong.

Keywords: Palliative care, Hong Kong, primary care, barriers 摘要

目的: 研究香港基層醫生對提供紓緩治療的意願和在實行時面對的障礙。

主要詞彙: 紓緩治療,香港,基層醫療,障礙 Introduction Down the centuries, doctors took care of families from birth to death and when people became sick, doctors provided treatments in the patient's homes. With advances in medical technology and specialisation, medical care has become institutionalised. Hong Kong is now facing an ageing population, where cancers and chronic debilitating diseases have become more common. Around one third of Hong Kong's overall mortality was due to malignant neoplasms and another third from chronic organ failure and vascular diseases.1 Along the natural course of the disease, cancer may develop metastasis with accompanying symptoms such as pain, dyspnoea and nausea with malnutrition as well as psychosocial and spiritual disturbances. Nevertheless, cancer-related sufferings can be relieved in more than 90% of instances.2 In Hong Kong, in-patient hospice palliative care services were established in 1981, while palliative home care services was provided by the Society for the Promotion of Hospice Care since 1985. Currently, palliative care is mainly provided by palliative care specialist in the hospital setting. There are 10 palliative care units in Hong Kong providing around 300 in-patient beds, with an in-patient to home-care ratio of one patient to four.3 Service demand cannot be adequately met, with only around 30 local palliative care specialists available. In 2005, around two thirds of cancer patients received palliative care and around half died in palliative care setting.4 In many countries, about 65% of cancer patients would want to die at home and eventually 30% were able to do so.5,6 In most parts of the world, palliative home care has been accepted as a standard mode of care for the terminally ill,7,8 with better quality of life for these patients during their last days.9,10 In Hong Kong, patients receiving palliative care had less admissions to acute and intensive care units, where more symptoms were documented and treatment offered, and they were mentally more alert during their last hours.4 It is a fact that family medicine and palliative care share similar philosophies, treating patients and families as a whole, using a bio-psycho-socialspiritual model and with a multidisciplinary approach. Emphases are also on continuity of care, coordinated resources, wider breadth of clinical knowledge and having good communication skills.11,12 Noting this, we set out to investigate if there were factors affecting members of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians and their attitude towards the provision of palliative care in their practice. Methodology As there was no local data on this topic, a combined qualitative and quantitative research method was adopted in this survey. A questionnaire (Appendices 1,2) was designed based on the results from three focus group discussions and five individual interviews,13 and piloted on twenty doctors. Our target population was all local members of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP). Demographic data, clinical qualification and experience, as well as attitudes and opinions towards palliative care in Hong Kong were requested. The questionnaire was sent out together with an invitation letter via the HKCFP mailing list and collected by return-paid envelope on a voluntary basis. Return envelopes were numbered and matched by HKCFP secretariat in order to check for non-respondents and ensure confidentiality. Two further rounds of mailings were sent at four weeks interval to non-respondents to increase response rate. Statistical analysis Data analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 15.0.14 Descriptive information for each explanatory variable was derived. Interdependence of observations (doctors' wish and actual provision of palliative care) was controlled using the Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) model. The GEE model and logistic regression analysis were used to determine factors that significantly contribute to doctor's wish and actual provision of palliative care in practice. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ethical consideration The project was approved by the Kowloon Central and Kowloon East Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Authority. Results Among the 1566 questionnaires sent out, 750 were returned. Seven members could not be reached because of invalid addresses, giving an overall response rate of 48.1% (750/1559). Nine responses were discarded due to incomplete answers. Demographics of our respondents and their response statistics are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

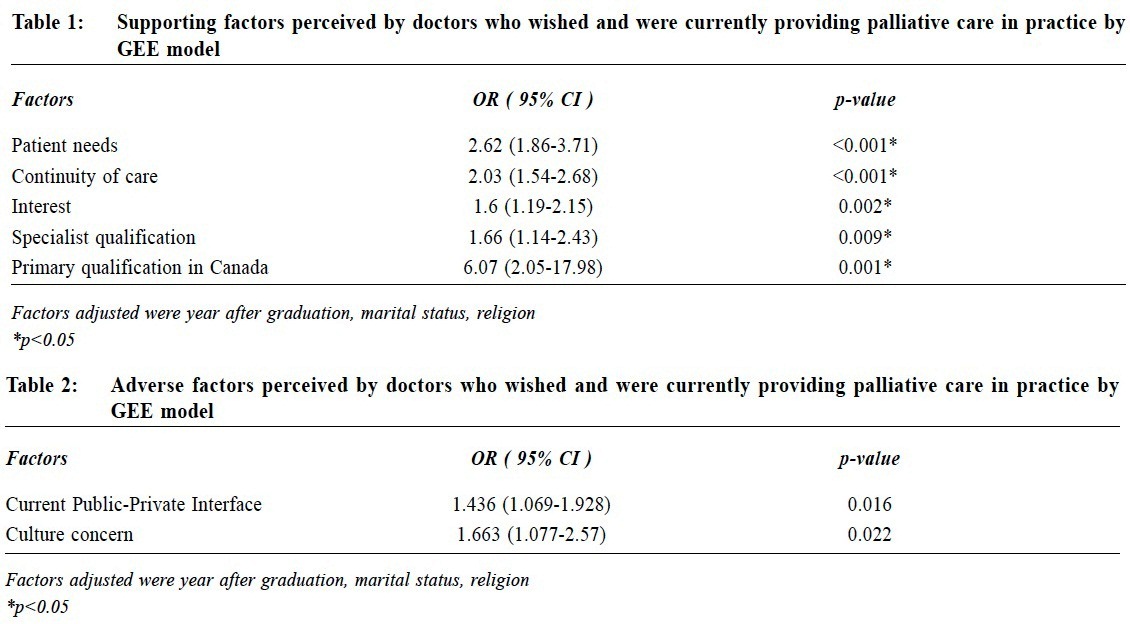

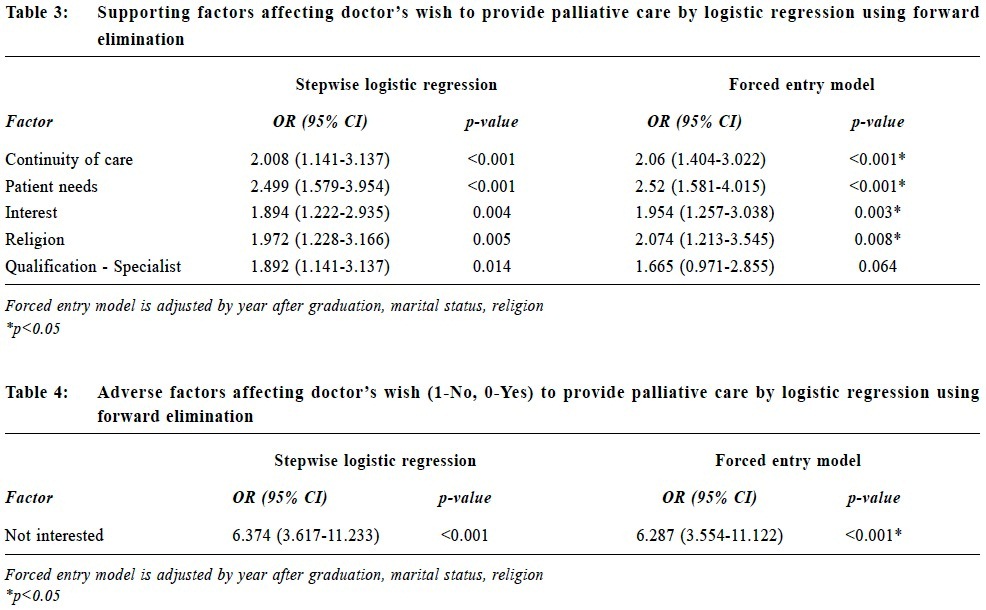

Among our respondents, 34.7% had graduated for more than 20 years. Most of them obtained their primary medical qualification in Hong Kong (74.9%). 19.7% were doctors with specialist qualifications in Hong Kong, the majority (82.4%) being specialists in family medicine. 56.2% were working in the private sector, among whom 64.0% of them were in solo practice. 61.5% had previous working experience in family medicine, only 1.2% had experience in oncology and 2.8% in palliative care. and 48.7% had no religious beliefs. 51.6% saw less than 6 terminal patients in the past year. Views on palliative care in Hong Kong Most doctors agreed that palliative care should be readily provided in the community (95.4%) and that primary care physicians should be involved in providing palliative care service (96.8%). 59.3% themselves preferred to die at home. 77.7% were willing to provide palliative care in their practice and 58.2% were currently providing some form of palliative care. Only 14.0% were providing home visits as part of their palliative care service. Knowledge on symptom control (80.6%), having multidisciplinary support (77.7%), experience in handling terminal patients (74.0%), training in interpersonal skills (psychosocial / counseling) (69.8%) and time available (69.0%) were considered essential for provision of palliative care in their practice. Time concern (77.1%) and not enough support from other disciplines (64.6%) were commonly considered as factors that discourage provision of palliative care in their practice. The most preferred format to learn about palliative care was workshop (63.6%), followed by seminars (57.2%), clinical attachment (54.0%) and attending a diploma course (38.9%). Majority of doctors thought that public education (80.8%) and networking with the palliative care specialists in hospital (75.3%) were important ways to promote palliative care service in the community. Factors perceived by doctors who wished and were currently providing palliative care in their practice Among doctors who were currently providing palliative care continuity of care (p<0.001), patient needs (p<0.001), interest (p=0.002), having specialist qualification (p=0.009), and obtaining their primary qualification in Canada (p=0.001) were significantly associated with a higher rate of wishing to provide and implementing palliative care in real practice (Table 1). Current public-private interface (p=0.016) and culture concern (p=0.022) were significant factors that would discourage this same group of doctors from wanting to provide palliative care in real practice (Table 2). Factors affecting doctors who would wish to provide palliative care Logistic regression using forward elimination was used to identify the factors supporting (Table 3) and factors adversely affecting (Table 4) doctors' wish to provide palliative care. After adjusting factors (year after graduation, marital status, religion), continuity of care (p<0.001), patient needs (p<0.001), interest (p=0.003) and religion (p=0.008) were reasons positively affecting a doctor's wish to provide palliative care, while having no interest (p<0.001) was the only significant factor that negatively influenced a doctor's wish.

Factors affecting doctors' actual provision of provide palliative care in their practice For doctors who wished to provide palliative care, logistic regression using forward elimination was used to identify the factors affecting their actual provision in their practice (Table 5). After adjusting factors (year after graduation, marital status, religion), knowledge / experience concern (p<0.001) and dealing with death (p=0.013) were found to be negatively influencing them to provide palliative care despite they had the wish. Discussion Demographics The overall response rate of 48.1% in our survey was lower than the response rates obtained in other similar kinds of questionnaire surveys conducted on primary care doctors (around 60-72%).15,16 Nevertheless, our respondents appeared to be representative of the HKCFP population as they had similar distribution in age and gender profile with our target population (Table 6). The low response rate may be due to their unfamiliarity with the topic of palliative care, the length of the questionnaire, and also absence of follow up contacts with the nonrespondents due to confidentiality reason.17

Attitude and practice of palliative care 77.7% of respondents reported that they were willing to provide palliative care and 58.2% were currently providing some form of palliative care in their practice and these figures were comparable to overseas countries.18,19 Home visits are common practice among overseas primary care doctors and may be considered an essential component of palliative care; whereas home visits appear to be provided by only 14% of our respondents. The importance of palliative care training in undergraduate years It was interesting to note that other than the behavioural and spiritual factors that promote palliative care provision, having a Canadian primary qualification was also found to be contributory. The Canadian undergraduate curriculum had outlined specific goals and objectives for palliative care in 1991,20 and the Educating Future Physicians in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EFPPEC) programme was also introduced to all medical schools in 2008. All Canadian medical students and residents would have received training in end-of-life care and were evaluated in their final exams, ensuring that every doctor in the country would be qualified with some palliative care training.21 Other countries such as UK 22,23 and Australia 24 were also incorporating palliative care into their undergraduate as well as postgraduate training. The World Health Organization has called for training institutions to make palliative care compulsory in courses leading to a basic professional qualification.25 Should the medical curriculum in Hong Kong make some changes to keep abreast with the international trend - to include more structured palliative care teaching in the early undergraduate years? Barriers against provision of palliative care More than half of the doctors thought that time concern and inadequate support from other disciplines discouraged them from providing palliative care in their practice. These types of barriers appear to echo the findings worldwide.11, 26-28 Concerning doctors' attitudes, having no interest in providing end of life care was the only significant adverse factor identified in the doctors' willingness to include palliative care service in their practice. Among doctors who were willing to provide palliative care, problems in dealing with death, as well as not enough relevant knowledge and experience, significantly discouraged them to actually provide palliative care. Inadequate undergraduate and postgraduate training in palliative care medicine was a known major barrier worldwide.22-24 Provision of palliative care not only involves dealing with patients' physical problems, but also having to consider their psychological, social and spiritual needs, which could be of considerable psychological burden to the doctor. Having adequate teaching and exposure could enhance doctors' ability to cope with the demand during the provision of palliative care. Barriers that discouraged the doctors who were providing palliative care included the public-private interface and cultural concerns. Hong Kong's public-private interface is still in its early phase, which focuses on information exchange. Nevertheless, palliative care requires collaboration between various disciplines and arranging in-patient care when required. A more mature system with bi-directional flow of information and a more structured networking and referral system with palliative care specialists and among other disciplines should help. Public Education Chinese people are in general less willing to express outwardly their feelings and needs.29 Cultural beliefs had been shown to have much influence on care-givers when taking care of terminal patients.30 Dying at home is not common in Hong Kong although most Chinese people would prefer to die in their own bed. Public education to arouse people's awareness and positive discussion on end-of-life care should be encouraged. Limitations As our target population was all the local HKCFP members only, compared with all primary care providers and general practice doctors in Hong Kong, the result may be biased because a more enthusiastic group in providing holistic care was selected. This study focuses on doctors' perspective only, but the provision of palliative care involves patient's and family's wish as well as multidisciplinary input. There may also be respondent's self report bias in the questionnaire survey. Conclusion Doctors having a mindset for family medicine should have a holistic attitude in caring for their patients. Most family doctors do appear to be interested to provide palliative care service in their practice and they have pivotal roles in coordinating palliative care service with their knowledge of the patients, community resources and networking with other disciplines. In addition to general and specific barriers, supportive factors and suggestions in the family physician's perspective on provision of palliative care in primary care were identified in this study. These factors should be addressed if collaboration between palliative care and primary care is considered for establishing community palliative care service in Hong Kong. Further studies in patients' and relatives' perspectives are needed to understand the actual need of the population in our local cultural context. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank all the participants in the questionnaire survey; Ms Teresa Lee and other HKCFP Secretariat members for administrative support; the General Office, Finance Department, Occupational Therapy Department and the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care staff of United Christian Hospital for administration assistance; and Mr. Edward Choi for statistical support. Funding This project was funded by the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP) Research Fellowship 2006.

Tin-chak Hong, MBBS(HK), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FRACGP, Dip Ger Med RCPS(Glas)

Resident Specialist Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital. Tai-pong Lam, PhD(Medicine)(Syd), MD(HK), FHKAM(Family Medicine), FRCP(Glas) Professor Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, The University of Hong Kong. David VK Chao, MBChB(Liverpool), MFM (Monash), FRCGP, FHKAM(Family Medicine) Chief of Service and Consultant Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care,United Christian Hospital. Correspondence to : Dr Tin-chak Hong, Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|