|

June 2013, Volume 35, No. 2

|

Update Articles

|

Practical challenges in ambulatory palliative care service in a regional hospital in Hong KongPo-tin Lam 林寶鈿 HK Pract 2013;35:52-58 Summary As the population ages, palliative care needs and demands for end of life care are growing. To meet this growing demand, ambulatory palliative care services are gradually gaining more and more importance. In this paper, the barriers and challenges facing the palliative care consult team, including flexible consultation format , late refer rals, concept of "Hospice" and recommendations not followed will be discussed. It is essential to facilitate choice of place of care and death in palliative care. Since October 2011 our hospital also launched the Palliative Virtual Ward Programme (PVWP) which is a home-based end of life care for home death, rendering our home death rate to be 2.6% for the first year. Cultural and social taboo, urbanisation, unavailability of informal caregivers and their support, limitation of 24 hours coverage by professional caregivers, and educational needs of health care professionals are all barriers and challenges that we meet. 摘要 伴隨人口逐漸老齡化,人們對紓緩治療需要和要求逐步增加,與之相應,紓緩治療門診服務也日趨重要。本文將就紓緩治療諮詢團隊所面臨的困難與挑戰,如彈性就醫模式、晚期轉診、"臨終關懷"的舊觀念以及不遵守相關建議等問題進行討論。 紓緩治療中,方便病患選擇關懷及死亡地點極為重要。自2011年10月以來,我們醫院啟動了為居家死亡提供居家臨終關懷的"紓緩虛擬病房項目(PVWP),我們醫院第一年的居家死亡率達到2.6%。文化和社會禁忌、城市化、缺乏非正規照顧者及其幫助、全天專業人員照顧的局限,未能做到24小時服務、醫務人員需更多訓練等因素,都是我們所遇到的困難和挑戰。 Introduction The United Christian Hospital, which is a regional general hospital in Hong Kong with emergency service serving a population of approximately 600,000, started its hospice and palliative care service in 1987. As Hong Kong's population ages and the pattern of diseases changes, the needs for palliative care services have become more and more important. To ensure that the palliative care service can run efficiently, prioritised palliative care services are to be provided in an integrated and sustainable way. The traditional hospice model within a specific building with emphasis on in-patient care was gradually transformed over the past six years into a comprehensive hospital model with an in-patient palliative care unit and an ambulatory palliative care service. Shifting the model of palliative care in a hospice institution to include ambulatory care could help achieve service outcomes and meet the increased demand of patient load.1 However, ambulatory palliative care services, which include palliative care consultative service, home based care, day services and out-patient clinic, do face barriers and specific challenges. This paper will focus on a discussion on consultative service and home-based end-of-life care for home death. The palliative care consult team Over the past years, we have shifted from a solo practitioner care model to a specialist-led team model consisting of the palliative care specialists, residents, specialty nurses and medical social workers. The aim of consultation has moved from service triaging to a comprehensive assessment of the physical, psycho-socio-spiritual needs of the patient suffering from advanced disease or a life threatening illness. Including more disciplines into a full team model means that more expertise are available to patients and their families, with the palliative care specialist as the team leader and the specialty nurse as the coordinator. During consultations, patients will be seen by both medical and nursing specialists. Overall, the palliative care team:

i) collaborates with the referring team, the patient and family members to achieve

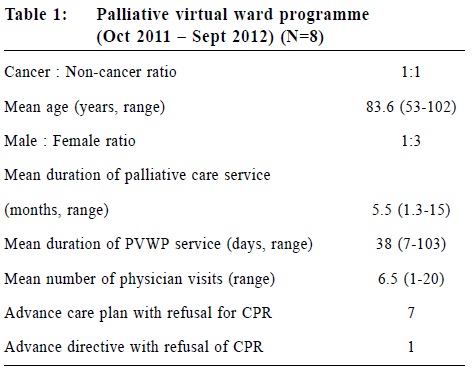

symptom control and address psycho-spiritual issues and define plan of management; Challenges facing palliative care consult team Given the large number of different referring teams with different expectations, our palliative care team must be flexible in adopting different consultation formats with different levels of intervention. For example, for experienced internists or medical subspecialists, we can just provide single visits by the palliative care specialist for assessment and advice on symptom control and further plan of care or to give advice and guidance without direct contact with patient (i.e. informal advice). For junior internists and residents, only short term interventions for specific problems are usually necessary for patients and/or their families. For surgeons, we usually provide on-going contact with them and the patients and/or arrange for them to take-over with the more difficult cases. Secondly, referrals usually come late in the course of the illness. This may be partly due to referring doctors old concept of "Hospice", which is still held firmly by some referring teams, that "Hospice" service is only for terminal cases or end of life and family bereavement care; late referrals may also be due to the unclear referral criteria for some non-cancer illnesses (especially chronic heart failure and chronic respiratory disease) which are not well known to the referring team and thus jeopardise the palliative care needs of these patients. In fact, nowadays, hospice and palliative care service should be provided and available to patients based on needs 2 when an incurable illness (such as advanced cancer, end stage renal failure, advanced respiratory disease or advanced cardiac failure) is diagnosed. Thirdly, there is a limited or narrow concept of what palliative care and consultation is all about. This may be partly attributed to the cultural attitudes of acute hospitals mainly focusing on curative treatment and may view palliative care as equivalent to "no-hope" and so not considering the patients for referral to palliative care.3 Our palliative care team has to spend time with the referring colleagues to introduce our mission and services, hence acting as a bridge to the full scope of palliative care services. Fourthly, our recommendations are sometimes not being followed by referring teams. This may be due to the fact that the referring teams do not possess the same attitude or skills shared by palliative care physicians, or they may simply not have enough time or interest for the time-consuming end of life care (e.g. advance care plan discussion) in the acute setting. Sometimes, they would just request those patients to be taken over by us. However, we should avoid too many "taking over" as this would de-skill their "end of life care" and even encourage patient abandonment. Instead, we attempt to communicate directly and frequently with the referring team and seek ways to partner pro-actively with them and maintain their sharing the responsibilities for the dying patients. Fifthly, implementation of "End of Life (EOL) care checklist" in acute setting. The feedback of staff from pilot implementation of EOL care checklist in 2011, which could serve as a supplementary tool to clinical care for dying patients, was encouraging (Appendix 1). However, further education on diagnosis of dying, EOL communication and bereavement care in acute setting are needed.4 Evidences did show that palliative care consult team could improve patient and family outcomes at the end of life, and earlier consultations might confer additional benefits.5-8 Hopefully, in near future, we can carry out service evaluation and outcome measure of our consult team. Home based end of life care for home death Patient's choice for place of care and place of death is considered an essential component and one of the main goals in palliative care. In countries where palliative care is well developed (e.g. UK, Canada), national policies facilitate patients to receive care and die in their preferred place. Overseas figures for home death ranged from 12.3 % to 60%.9-13 Indeed, palliative home care enhances the patient's and family's independence and psychological well being as the home is a place of familiarity and comfort without institutional regulations. Privacy, autonomy and better bereavement could also be enhanced.14 For many years, Hong Kong followed the "palliative care nurse-based team" model.15 Service provision was limited since there were few well developed palliative care units with palliative care specialist input. From the legislation perspective, the occurrence of natural death at home is not reportable in Hong Kong, However, the home death rate has been extremely rare, and there is no official local figure. Our recent survey found that among palliative care patients, 37% and 19% preferred home as place of care and place of death respectively.16 Reasons for and against our extremely low home death rate include social and cultural factors; death is indeed a taboo subject for Hong Kong Chinese people, together with lack of public education on death and dying. With urbanization, access into the hospital and the availability of hospital in-patient beds become easy, and dying in the hospital become a natural event to follow. For those who have self-owned flat, the concept of a "haunted house" also adversely affects the value of property and this discourages people dying in their own home. Having or not having the availability of family members as informal caregivers, nurse based home care team, specialist and family physicians are all important elements for sustainable service for home death. Evidence suggests that the use of EOL home care programmes can increase the number of patients who will want to die at home.17 The Palliative Virtual Ward Programme is a home-based end of life care for home death programme that was launched in our hospital in October 2011. This "Dying at home" is promoted through a concerted effort among members of our palliative care team, home care nurse, community nurse, emergency department, hospital mortuary and the death certificate office. When a death takes place, the deceased body is brought to the emergency department of the hospital for death verification and subsequent transfer to hospital mortuary without admitting the patient to hospital. The palliative care physician will then sign the death certification. During the first twelve months, a total of eight patients successfully fulfilled their last wish to die at home (Table 1), rendering our hospital home death rate to be around 2.6 %.

Challenges of home based EOL care for home death This programme encountered several challenges and barriers. First, although the preference for dying at home is low in HK, there are still a certain percentage of patients who think of doing so. Home de a th should only be promoted after exploring individual's preferences, at the same time providing options and facilitating patient's choice. Our experience tells us that choice is better initiated by the patient and fully supported by the family members as caregivers. Availability of certain drugs and their route of administration in the community is another challenge for our palliative care team. The practicability of uncommon routes of administration for some medication (e.g. by the rectal, sublingual, transdermal route) and provision of new medications must be explored before home care can take place. Parenteral opioids are useful for symptom control; but in the era of risk management, various barriers prevent implementation of parenteral opioid in the community, creating a difficult dilemma for community-based end of life care. To date, there are no corporate guidelines for health care professionals on drug administration at a community level. It is difficult to meet the needs of the dying at all times, and this is important in facilitating home death. Due to limited manpower resources, our home palliative care team cannot provide 24 hours coverage. At present, our ambulance crew and the police force have no specific policies for care of the dying or allowing natural home death. Although all of our eight patients had either made advance care plan or given advance directive with a refusal of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), most ambulance paramedics would still provide CPR to the patient during transfer to AED. Related health care policies should be developed in collaboration with the Fire Service Department who runs the ambulance service and Police Department at a corporate level. To go a step further, the deceased should be allowed to be brought directly from home to the funeral parlour without a hospital transit. Last but not least, the public should be continually educated on the philosophy of palliative care and home death. In addition, palliative medicine should become an essential component of family medicine training,18 thus hopefully, to further strengthen our care for patients to go through their smooth journey from illness to death, and subsequently for their relatives. Conclusions Barriers and challenges exist for ambulatory palliative care services. It is essential to facilitate choice of place of care and place of death. Continuous professional education on end of life care to hospital staff and family physician is important, while public education on death and dying, philosophy of palliative care and home death should be enhanced.

HA UCH End of Life Care Checklist for Dying Patient

Po-Tin Lam, MBChB, MRCP (UK), FHKCP, FHKAM (Med)

Head, Division of Palliative Medicine, Senior Medical Officer, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital Correspondence to : Dr Po-Tin Lam, Department of Medicine & Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR. Email: lampt@ha.org.hk

References

|

|