|

June 2013, Volume 35, No. 2

|

Update Articles

|

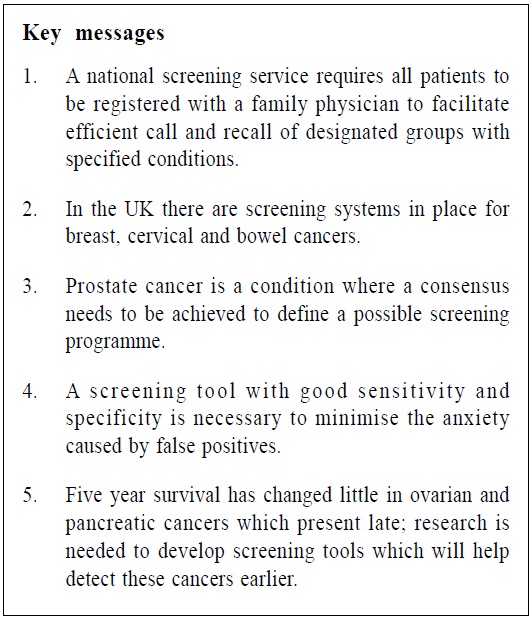

Cancer screening, referral pathways and care in the UK – An updateRodger Charlton Rodger Charlton HK Pract 2013;35:59-62 Summary This paper summarises the presentation given at the 19th Hong Kong International Cancer Congress (HKICC) on 8th November 2012.1 The objectives of this article detail cancer screening in the UK, consider the cancer care issues relating to screening and provide some information about referral pathways, thus the paper gives an insight into the patient journey. 摘要 本文是2012年11月8日在第19屆香港國際癌症大會(HKICC)上報告論文的總結。本文旨在詳述英國癌症篩查的狀況,思考與篩查相關的癌症關懷方面的問題和爭論,提供轉診路徑有關的資訊,從而使讀者對患者的全流程有較深的瞭解。 Registration with a GP In the UK, all the general public are registered with one general practitioner (GP) whether practising as a solo or in a group practice. There is no fee to see a GP in the UK and GPs' salaries are funded indirectly through the national insurance which are contributed from employed citizens. Those not in employment, children or the retired, are also entitled to free National Health Service (NHS) care. GPs are self-employed and sub-contract their services to the NHS. In return for registering patients and providing what is referred to as General Medical Services (GMS), GPs receive reimbursement in a complex and indirect way for this GMS and other services to a registered population of patients. The key point is that since the establishment of the NHS in 1948 all members of the public are entitled to free primary and secondary health care at the point of access. Registration and screening Patients are registered with GPs and this facilitates call and recall of patients for various screening procedures, including cancer. In the same way, GPs can act on screening results and play a necessary and important coordinating role. Altogether these help to establish national screening policies. Nevertheless, these policies may be interpreted differently within different regions of the United Kingdom (in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) because of government devolution. For example, in relation to screening programmes each part of the UK can determine when, and how, to put those policies into practice. As a result there is no antenatal screening for Down's syndrome in Northern Ireland for cultural/ religious reasons and staggered implementation of the programme for aortic aneurysm screening in the UK according to costs and organisation. Screening is free to designated groups depending on age. There may also be local variations and initiatives with local screening programmes which will be in addition to national screening programmes. Some of the screening is delivered by primary care and some not. The focus of this article is on England's national screening programmes (breast, cervical and bowel cancers) as there are some minor variations in cancer screening in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This paper will also discuss other cancers which may in the future be screened for in the UK. Breast cancer screening This provides free mammography every 3 years for all women aged 50 and over. This is a rolling programme so that every woman receives an invitation before her 53rd birthday. The upper age limit is 70 but depending when the woman receives the invitation the final age of screening may be at 73 years of age. If an abnormality is detected, both the patient and her GP are informed, and the patient will receive an appointment for a secondary care consultation. The GP is also notified if patients do not respond to a screening invitation or fail to attend a booked appointment for screening. To increase uptake many areas employ the use of mobile screening units. Cervical cancer screening This is offered every three to five years to all women between the ages of 25 and 64 years. Screening using liquid cervical cytology with a brush is mainly performed by trained practice nurses, who are employed by the GP practice. Three yearly screening intervals are provided for those aged 25 to 49 years, and five yearly for the aged 50 to 64 years. Those aged 65 and over are only screened if they have not been screened since 50 years of age or have had a recent abnormal test. For the 25 to 64 age group, if a test is abnormal or a specimen inadequate, the test will either be repeated within 3-12 months or a colposcopy referral arranged accordingly. The screening interval then may be increased until a normal cervical cytology result is achieved. The cervical screening programme has been present in the UK for many years, which has succeeded based on patient registration and ensuring optimum recall and follow-up. The introduction of liquid based cytology and identifying practitioners who regularly return inadequate specimens allows further training and improving skills and so competence. In the last 20 years, 81% of women were screened resulting in about 64 million cervical screenings and over 400,000 significant abnormalities detected. It has been estimated that cervical screening in the UK saves 4500 lives each year and can prevent around 75% of cancer cases in women who attend regularly.2 Future of cervical cancer screening In September 2008 a national programme was started to vaccinate girls aged 12 to 13 with Gardasil. This was considered important since cervical cancer is the second commonest cancer in women under the age of 35, with nearly 3000 women diagnosed with cervical cancer annually. Screening in the future may also include an HPV test alongside cervical cytology (termed "co-testing"). Those with a positive HPV test are at higher risk and may need to be screened more often. Good immunisation uptake will have implications for cervical screening in the future, both in terms of how often and when women are screened. Vaccinated individuals could be safely offered their first cervical screen much later than the current age of 25. However, some will argue that this could lead to a false sense of security given the many strains of the virus and the immunity provided by the current vaccine. This is an area of screening that will therefore continue to develop and so change. Bowel cancer screening This programme using faecal occult blood as the screening tool started in July 2006 and achieved nationwide coverage by 2010. There are local community hubs which coordinate the programme. Approximately 98 in 100 people will receive a 'normal' result and will be offered a further test in two years. About 4 in 100 people the test may initially be 'unclear' and the test will be repeated up to two more times. Overall, approximately 2 in 100 people will have an 'abnormal result'. They will be offered an appointment with a specialist local bowel cancer screening centre to consider colonoscopy. The age groups that are offered bowel cancer screening differ among the 4 countries of the United Kingdom as follow: England 60-74 years, Scotland & Wales 50-74 years and Northern Ireland 60-71 years.3 Bowel cancer screening, however, is still in its infancy in the UK. The screening programme initially aimed for a 16% reduction in overall bowel cancer deaths. However, a recent paper in the British Medical Journal reported on how one in four cases of bowel cancer in England is diagnosed only after emergency admission.4 This is particularly poignant as bowel and, treatment can be very effective and in some cases curative if detected early. Unfortunately, the average uptake for screening is less than 55% 5 and publicity about bowel cancer and why screening is important is now promoted regularly in the media. Prostate cancer The most common cancers in the UK are breast, prostate, lung and bowel cancer. Despite this there is no national screening programme for prostate cancer. This is referred to as "an informed choice programme" but is not approved by the National Screening Committee.6 Therefore GPs have a big role in screening for prostate cancer and enabling patients to have an informed choice. The difficulty lies in the sensitivity and specificity of the most commonly used tool for screening, the serum prostate specific antigen (PSA). If a result is high, an invasive biopsy is indicated, but arguments are being made that an MRI scan may be more effective in picking up prostate cancer and less invasive with fewer side-effects, but as yet there is no evidence base for this. Until a biopsy is done it is not possible to give an accurate prognosis using a Gleason score. Consensus on managing patients with raised PSA results has not been achieved despite availability of both local and national guidelines. As a result each patient needs a negotiated and agreed individual management plan which may just include watchful waiting. Treatment has the potential to cause more problems than the disease itself whether that would be by hormone therapy, radical surgery or radiotherapy. GPs often find it challenging to explain the implications of PSA levels among different age groups, contributing to why prostate cancer is currently not part of the UK national screening programme. Advising patients regarding whether to have a PSA test or not is therefore a potential clinical minefield. Future screening programmes Two rare cancers, but nevertheless with devastating consequences are cancer of the ovary and cancer of the pancreas. Both tend to present late and treatment is usually unsuccessful. There are no national screening programmes for these two cancers. Raising attention to these two cancers. Research into earlier recognition are important. Ovarian cancer 75% of patients with ovarian cancer present with advanced incurable disease with a 30% five year survival rate. Two main tests have been used in screening trials for ovarian cancer; CA125 and transvaginal ultrasound. However, only about 85% of women with ovarian cancer have raised CA125 and only 50% of early stage ovarian cancer have raised CA125. To complicate matters other conditions such as fibroids and pelvic inflammatory disease are also associated with raised CA125. There is even some evidence to suggest that ovarian cancer can be misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome.7 Pancreatic cancer Again there is no national screening tool. Five year survival rates for pancreatic cancer have remained static at 3% in the last 40 years. The only potential cure is surgical and most people present too late for surgery. 47% of cases are diagnosed in hospital emergency departments. It is referred to as the fifth biggest cancer killer in the UK but it only receives 1% of funding.8 This is another cancer where further research to discover an early indicator or 'red flag' is required and a screening tool. Referral pathways In the UK when cancer is suspected there is a referral pathway called "rapid access" which guarantees specialist assessment within two weeks. This is an enormous advance and very helpful to GPs who are patients' advocate by default. Age criteria apply but examples of symptoms which can be used to trigger rapid access include: rectal bleeding, recent change in bowel habit, haematuria, haemoptysis, a new suspicious mole, post menopausal bleeding, difficulty swallowing and new onset anaemia suggestive of chronic gastrointestinal haemorrhage. These rapid access clinics also exist for other conditions, such as when ischaemic heart disease is suspected. Although referral criteria are determined locally according to needs, this rapid access service is available to all GPs nationally. Conclusions The National Health Service in the UK is well-suited to screening since the entire population is registered with GPs (www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk). GPs are pivotal to screening by advocating these programmes and referring patients early when cancer is suspected. Screening programmes which are run or facilitated by GPs are key factors in reducing cancer morbidity and mortality. Figures from the Office for National Statistics show that almost a third of people still die from some form of cancer in the UK and this continues to be a great challenge to healthcare.

Rodger Charlton, MPhil, MD, FRCGP, FRNZCGP

Associate Clinical Professor and General Practitioner Division of Primary Care, Nottingham University, UK Honorary Professor College of Medicine, Swansea University, UK Correspondence to : Professor Rodger Charlton, Division of Primary Care, Nottingham University, UK.

References

|

|