|

September 2013, Volume 35, No. 3

|

Original Articles

|

Knowledge and perceptions of stroke risk factors among primary care Chinese patients who had previous history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack in Hong KongCatherine XR Chen 陳曉瑞, To-fung Leung 梁濤峰, Sze-luen Chan 陳仕鑾, LA Tse 謝立亞, King-hong Chan 陳景康 HK Pract 2013;35:80-90 Summary

Objective: To explore the knowledge and perceptions about stroke

risk factors among primary care Chinese patients with previous history of stroke

or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and to identify possible associations with patient

characteristics and control of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors.

Keywords: stroke, cardiovascular risk factors, knowledge, perception and primary care. 摘要

目的: 瞭探討基層醫療複診的中風的中國病人對心血管危險因素的知識和認知情況,並探討其與病人背景資料及心血管疾病危險因素控制之間的關係。

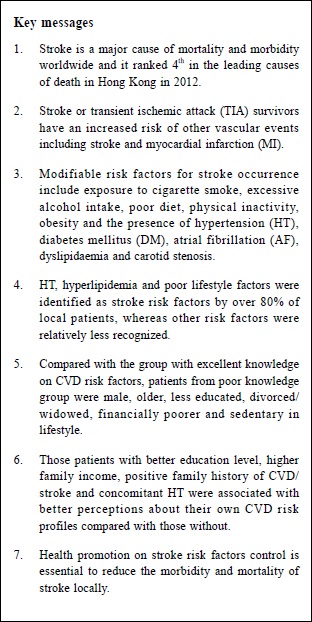

主要詞彙: 中風,心血管疾病危險因素,知識,自我認知,基層醫療。 Introduction Stroke is a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Locally, according to the latest health statistics published in the Department of Health, cerebrovascular disease ranked 4th in the leading causes of death in Hong Kong in 2012.1 Stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) survivors have an increased risk of a recurring stroke 2 and other vascular events including myocardial infarction (MI).3 Epidemiological studies have proved that modifiable risk factors for stroke occurrence include exposure to cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol intake, poor diet, physical inactivity, obesity and the presence of hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), atrial fibrillation (AF) and dyslipidaemia.4 Clinical trials have provided strong evidence that effective secondary prevention significantly reduces the recurrence rate and mortality rate of stroke and therefore improves its clinical outcome.5,6 Locally, asignificant proportion of stroke survivors are managed in the primary care 7 and are followed up in the GOPCs. Local data obtained from a clinical audit conducted by the same research team on the secondary prevention of stroke have demonstrated that marked deficiencies existed in the assessment of CVD risk factors among non-acute stroke patients managed in the primary care.8 The reasons behind these deficiencies are multi-factorial. At patient level, stroke patients often lack the knowledge and perceptions about the control of CVD risk factors and therefore may have compliance problems with medical advice and treatment. Indeed, several lines of evidence have suggested that gaps in professional and public stroke-related knowledge do contribute to this problem.9,10 Poor understanding of stroke risk factors has been demonstrated in the general population 11 as well as the high risk population for stroke 12,13 and the stroke survivors.14 Locally, Dr. R T F Cheung and his group had conducted a random telephone survey on the knowledge of stroke in Hong Kong Chinese in 1999,15 and found that most respondents could recognize the warning symptoms of stroke. However, there is no local data from Hong Kong Chinese stroke patients regarding their knowledge and perceptions of CVD risk factors and this information is definitely important to the setup of intensive public education programme locally about stroke prevention. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the knowledge and perceptions about stroke risk factors among primary care Chinese patients with previous history of stroke or TIA and to identify possible associations with patient characteristics and control of CVD risk factors. Methodology Design: Questionnaire-based cross-sectional study Subjects: All non-acute Chinese stroke patients with coding by International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC): K89 (transient ischaemic attack), K90 (cerebrovascular accident) and K91 (cerebrovascular disease) and had been regularly followed up at GOPCs of KCC from 1st January 2012 to 31st December 2012 were recruited. However, patients were excluded if they were acute stroke cases within 4 weeks of onset; being followed up by other clinics; had been certified dead or unwilling to join the study; not communicable, with hearing impairment, language barrier or dementia and who were not of Chinese in origin. The questionnaire A four sections questionnaire was specifically designed for this study and was translated into simple Chinese for easy use. It was based on a literature review of previous studies concerning patient's knowledge about stroke/TIA and stroke/TIA risk factors. The content has been validated by two neurologists from the Department of Medicine, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, KCC. The questionnaire was piloted to 30 patients and the reliability test using Cronbach Alpha resulted in the value of 0.86. Thereafter, all stroke/ TIA patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were asked to complete the questionnaire after their routine follow up for chronic diseases and then interviewed by one trained research assistant. Each interviewer conducted a standardised, structured, one-to-one interview with open ended questions. The interviewer assisted the interviewee only by clarifying any lack of understanding, if required. No attempt was made to prompt the subjects by suggesting answers directly. The first section of the questionnaire gathered demographic information including age, gender, education level, living status and financial status. The second section consisted of questions to explore stroke patients' knowledge on risk factors for stroke recurrence.14 CVD risk factors including old age, male gender, smoker, excessive alcohol drinking, obesity, lack of regular exercise, poor diet control, family history of stroke/CVD, past history of stroke, presence of hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidaemia, atrial fibrillation (AF) and carotid stenosis were listed in the questionnaire and 6 unrelated conditions (allergy, liver disease, thyroid problem, osteoporosis, chronic lung disease and rheumatoid disease) were added as distracters. The third section gathered patient's own perceptions on his/her risk factor profiles, target blood pressure and self-assessment on drug compliance. Patient's existing CVD risk profiles were reviewed from the CMS and their chronic conditions with stroke, DM, HT and hyperlipidemia documented in the fourth section. Background information of the patients The recruited patients' age, gender, smoking status, body mass index, blood pressure (BP), lipid profile and Haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) if diabetic were collected from the medical records of the Clinical Management System (CMS). The most recent records of BP reading and blood test were used for analysis if more than one reading had been performed during the study period. BMI was calculated as Body Weight (kg) / Body Height (m).2 The patient was considered as a smoker if he/she currently smoked or was in the first six months of cessation. Co-morbidity with HT, DM, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and hyperlipidaemia were retrieved by ICPC code from the CMS. Repeated systolic blood pressures of ≥130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressures of ≥80 mmHg confirmed a diagnosis of HT in diabetic patients.16 The patient was considered to have hyperlipidemia if his/her low density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration was >2.6mmol/L, total cholesterol >5.2mmol/L or triglyceride >1.7mmol/L.17 Calculation of stroke-patients' knowledge score and perception score Patients was granted one point if he/she correctly identified one of the listed 14 CVD risk factors or successfully spotted out one of the 6 distracters. Therefore, 20 was the full knowledge score. Those patients who achieved 16-20 in the knowledge score was grouped as "excellent knowledge group", 10-15 as "good knowledge group" and less than 9 as "poor knowledge group". Perception score was calculated as the ratio of correctly self-identified CVD risk factors over his/her existing CVD risk profiles retrieved from the CMS. The lowest perception score was 0 and the maximum was 100%. Statistical analysis All data were entered and analysed using computer software (Windows version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). Student's t test and analysis of variance were used for analysing continuous variables and Chi-squared test for categorical data. Pearson's correlation was used to determine the association between patient's knowledge score and perception score. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the associations between patient's perception scores (score ≥70% vs. score <70%, using a cutoff point of 70%) with their age, gender, socioeconomic factors and their existing CVD risk factor profiles. All statistical tests were two sided, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ethics This study was approved by Joint Ethics Committee of KCC and KEC, Hospital Authority of Hong Kong (Ref no: KC/KE 11-0090/ER3). Results Study population and the response rate A list of 3445 stroke patients followed up at 4 GOPCs of KCC from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2012 was generated from the CMS. Among these patients, 1864 patients were excluded due to the exclusion criteria as described above. Among the 1581 cases fulfilling the inclusion criteria, 580 patients declined joining the study and therefore the remaining 1001 patients who completed this questionnaire study were recruited for data analysis. The overall response rate was 63.3% (Figure 1).

Table 1 summarised the demographic characteristics, social factors and co-morbidities of non-acute Chinese stroke patients recruited into analysis. Most of them (90.2%) suffered from cerebral infarct or TIA and 9.8% from intracerebral haemorrhage. The mean age for all study population was 69.6 ± 9.7 years and 462 cases were female (46.2%). The mean time from their first ever stroke/TIA registered was 61.5 ± 21.7 months. Most of them were from the lower socio-economic class with monthly family income < HK$10,000 or were on CSSA (826, 82.5%) and only 375 (37.5%) completed upper secondary education or a higher education level. With regard to their co-morbidities, 901 (90.0%) had concomitant HT, 341 (34.1%) had DM, 705 (70.4%) had hyperlipidaemia, 106 (10.6%) had IHD, 80 (8%) had AF and 15 (1.5%) had history of carotid stenosis.

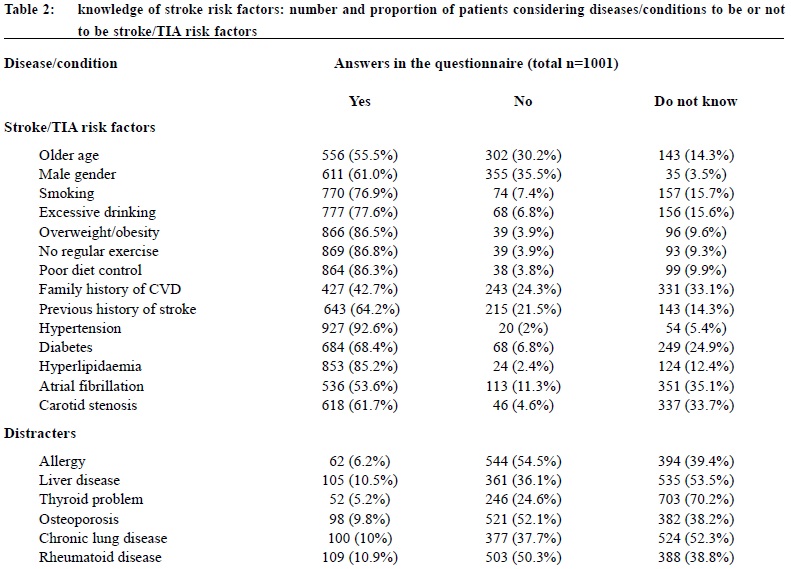

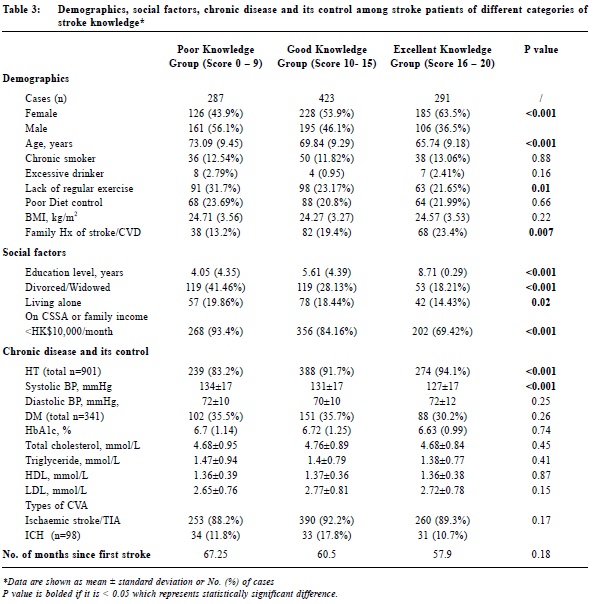

Patient's knowledge of stroke/CVD risk factors The risk factors that were most often identified by stroke patients were hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and lifestyle factors including obesity, poor diet control and lack of regular exercise (all >80%), whereas old age (55.5%), male gender (61%), DM (68.4%), AF (53.6%) and carotid stenosis (61.7%) were relatively less recognised (Table 2). Only a small proportion (around 10%) of patient considered medical conditions that were not stroke/TIA risk factors (distracters) as stroke/TIA risk factors, but 38.2% to 70.2% of patients answered "do not know". The differences in patients' demographics, social factors and disease control when stroke patients were categorised according to their knowledge score on CVD risk factors are summarised in Table 3. Most stroke patients had good grasps of stroke/CVD risk factors with a knowledge score of 10-15 (n=423, 42.3%). It is clearly shown that, compared with excellent knowledge group, patients from poor knowledge group were more to be male, older, less educated, more divorced/ widowed, financially poorer (all P<0.001) and more sedentary in life style (P=0.01). Those patients who had positive family history of stroke/CVD or with concomitant hypertension were found to have better knowledge on CVD risk factors. With regard to disease control, the average systolic blood pressure of stroke patients from poor knowledge group was much higher than those from excellent knowledge group (134 ± 17mmHg versus 127 ± 17mmHg, P<0.001) but their BMI, metabolic control, lipid profiles and diastolic blood pressure were comparable (all P>0.05).

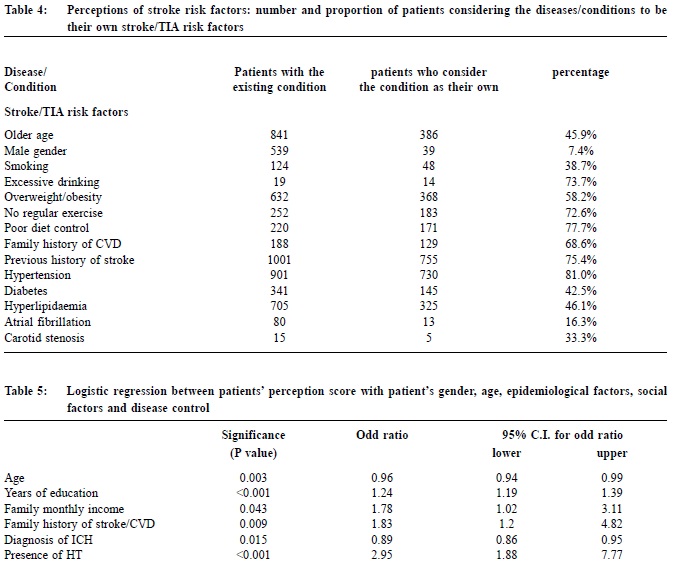

Patient's perceptions of his/her own CVD risk profile A large proportion of stroke patients could not identify their own CVD risk factors. Only 138 patients (13.8%, 61 male and 77 female) were able to correctly recognise over 70% of their own risk factors. More male patients had poor perception score about their own CVD risk factors (<55%) compared with female patients (P<0.05). Similar to patients' knowledge about CVD risk factors, the most common self-perceived risk factors that could be identified by stroke patients were hypertension (81%), poor diet control (77.7%), lack of regular exercise (72.6%) and excessive drinking (73.7%), whereas the other risk factors were less recognised (Table 4). Pearson's correlation study, however, suggested that the correlation between knowledge of stroke risk factors and self-perception was poor (r=0.19, P<0.001). Multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that older age and having a diagnosis of ICH were associated with poor perceptions of stroke/TIA risk factors, whereas patients with better education, higher monthly family income, who reported that they had a family history of CVD/stroke or with co-morbidity of HT were found to have higher levels of CVD risk factor perception (Table 5). When stroke patients were asked to categorised their own CVD risk, only less than half (n=408, 40.8%) correctly perceived that their CVD risk was high, with 193, 277 and 123 choosing medium, low and no CVD risk respectively.

Knowledge about treatment for reducing the risk of having a new stroke/TIA Most hypertensive stroke patients knew the target blood pressure. 221 diabetic stroke patients (64.8%) knew that their ideal blood pressure should be under 130/80 mmHg and 581 non-diabetic stroke patients agreed that their blood pressure should be controlled under 140/90 mmHg (88.0%). However, only 47.5% (n=162) diabetic stroke patients knew that their HbA1c should be below 7%. When drug compliance was assessed, most (n=929, 92.8%) reported having satisfactory drug compliance with regular drug intake. Discussion This study is a large clinical survey ever conducted locally on the knowledge and perceptions of CVD risk factors among Chinese stroke patients managed in the primary care. It showed that stroke/ TIA patients' knowledge and perception about stroke risk factors varied among patients with different characteristics, social factors and co-morbidities. It provided important background information for initiating a comprehensive community education programme addressing the issue of secondary prevention on stroke.

Some disease conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and poor lifestyle

factors including obesity, poor diet control and lack of regular exercise could

be identified as CVD risk factors by over 80% of stroke patients and were also recognised

as their own risk profiles. These findings are comparable with studies carried out

in European countries.14,18 Our findings are expected with the extensive

health promotion on lifestyle modifications and blood pressure control among our

hypertensive patients. In addition, the introduction of reference frameworks on

management of HT locally which covered primary prevention and lifestyle changes,

assessment of high risk groups and early detection and management of hypertension

helps to ensure the quality of care for hypertensive and hyperlipidaemia patients

within the community.19 Moreover, the implementation of Risk Assessment and Management

Programme (RAMP) and Patient Empowerment Programme (PEP) for hypertensive patients

within the Hospital Authority On the other hand, it is important to note that diabetes (68.4%), atrial fibrillation (AF, 53.6%), carotid stenosis (61.7%) and previous history of stroke/TIA (64.2%) were comparatively less recognised as CVD risk factors. Poor understanding of the fact that diabetes could be a stroke/TIA risk factor was observed by Sloma et al in a study conducted among people with prior history of stroke in Sweden.14 Studies carried out in India, however, showed that diabetes was among the best known stroke/TIA risk factors, at the same level as hypertension, smoking and excessive intake of alcohol.20 In the prevention and education of diabetes patients, more emphasis has been attached to the glycaemic control and early detection of microvascular complications, therefore macrovascular complications including stroke/TIA may have received less attention. To our surprise, only 64.2% of patients could identify the fact that a previous history of stroke/TIA was associated with an increased risk of having a new stroke/TIA. This is also reflected in the subsequent question on how to categorize your own CVD risk, with less than half (n=408, 41.8%) of stroke patients agreeing that their CVD risk was high and 12.3% (n=123) even thought they did not have increased CVD risk at all. This finding is alarming given the high recurrence risk of stroke and other cardiovascular event in survivors of stroke/TIA. Comprehensive education programme addressing this issue should be advocated to improve the attention and overall alertness of stroke survivors. Many studies in the literature have shown that socioeconomic status (SES) influence patient's knowledge about stroke/TIA risk factors.21,22 Older age, male sex, lower educational levels and lower family income have all been commonly associated with a poor knowledge of CVD risk factors and this is in line with our findings. Indeed, it has been shown consistently that SES is inversely associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.23 Higher incidence of stroke, stroke risk factors, and rates of stroke mortality are generally observed in low socioeconomic groups compared with those in high socioeconomic groups. Less evidence is available to study the association between socioeconomic status and stroke recurrence or temporal trends. Those with a lower socioeconomic status are more at a disadvantage and are less likely to receive appropriate stroke services. Therefore, innovative prevention strategies targeting people in low socioeconomic groups are required along with effective measures to promote access to effective stroke interventions worldwide. With regard to the CVD risk factor perception, a large proportion of stroke patients could not identify their own risk profile, with only 138 patients (13.8%) being able to correctly recognise over 70% of their own risk factor profile. These findings were similar to studies carried in the United States showing that only 20% of stroke cases accurately estimated their risk for a recurrent stroke.24 Patients with better educ a t ion, highe r monthly f ami ly income , who reported that they had a family history of CVD/stroke or with co-morbidity of HT were found to have better levels of CVD risk factor perception compared to those without. This could be the result of more frequent contacts with medical care or recruitment into chronic disease management programmes among chronic disease patients managed in HA. Stroke patients were usually highly motivated to avoid a further stroke and developed a strong focus on blood pressure control. This was reflected in the subsequent question asking about the target blood pressure if the patient was hypertensive. Most of stroke patients (n=802, 80.1%) knew their target of blood pressure control and more than 90% (n=929, 92.8%) has reported satisfactory compliance to drug treatment. Perceived risk is considered to be the primary motive to change within the Health Belief Model 25, which assumes that, the higher the perceived threat, the more likely an individual will modify his or her behaviour to circumvent that threat. After stroke or TIA, most survivors changed their behaviour in ways that would contribute to stroke risk reduction. Results of our study indicated that one's education and family history had direct influence on one's level of perceptions regarding the CVD risk factors and helped us to identify stroke patients who were more likely to have poor risk perception and therefore in need of early intervention. Implications to the primary care Community health education and promotion are an integral part of Family Medicine in which family physicians have played an essential and critical role. To develop effective health-promotion interventions on CVD risk factor control among high risk populations, family physicians need to understand the knowledge and perceptions of stroke patients and explore the potential barriers specific to these individuals. This study has provided important background information on the knowledge and perception of CVD risk factors among Chinese non-acute stroke patients and alerts family physicians about the importance of CVD risk factor education and promotion among stroke patients managed in the primary care. We believe that learning about the knowledge and perception of stroke patients on their CVD risk factors and stroke treatment will help to increase patients' awareness about stroke management and prevention. In addition, these findings will have implications for developing more effective strategies to educate local Hong Kong Chinese patients about stroke prevention. Limitations of this study There are several limitations in this study. First, only stroke patients who had been regularly followed up in the GOPCs of KCC were recruited, therefore selection bias might exist. The response rate being 63.3%, although comparable to those reported in the literature, may render self-selection bias inevitable. However, we have compared the major epidemiological characteristics between the respondents and the non-respondents and found that there was no obvious difference. Since a large proportion of stroke patients followed up in our GOPCs were from lower-income groups, the proportion of "poor knowledge groups" might be overestimated. In addition, these findings might not be directly applicable to private setting or specialist setting. However, the present findings may lay important groundwork for further studies locally and internationally. Secondly, the questionnaire was specially designed for this study as we could not find any validated Chinese questionnaire in the literature that was suitable. Nevertheless, as numbers of variables are based on the objective measurement, misclassification bias, if present, should not be regarded as a major issue. Thirdly, the concomitant chronic diseases with HT, DM, IHD and AF in stroke patients were retrieved by ICPC code in the CMS. Inadequate ICPC coding may therefore underestimate the co-morbidity rate of these conditions in stroke patients. Lastly, because of the cross-sectional nature of our study, no temporal or causal relationship could be established. Therefore, the results from this study would be confirmed by analytic studies. Conclusion In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that significant number of Chinese stroke patients lack the knowledge and perceptions required to prevent stroke recurrence. This should alert family physicians on the importance of CVD risk factor education and of setting up effective secondary prevention strategies among stroke patients managed in the primary care. To address the issues raised in this study, we plan to initiate Stroke and Heart Disease Programme and promote CVD prevention and self-empowerment in the primary care. This programme will consist of multiple components, including a media campaign, educational materials and conferences, programmes that address behaviour change and ongoing grassroots initiatives. We believe that this will help to enable Chinese stroke patients to reduce their risk of stroke recurrence through improved lifestyle and better prevention practices and improve their cardiovascular outcome in the long run. Acknowledgements This study was funded by the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians Research Fellowship award 2011. I am wholly indebted to the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians for the generosity and support given to the research development in the primary care. I sincerely thank Dr King Chan for his continuous inspirations and encouragement during this study. I am also grateful to Ms Elise Chan for her great effort in conducting the interview, collecting the data and performing the statistical analysis. We would also like to thank all clinic staff of Department of Family Medicine and GOPC, KCC for their unfailing support, without which this study would not have been possible.

Catherine XR Chen, PhD (HKU, Medicine), MRCP (UK), FRACGP, FHKAM (Family

Medicine)

Associate Consultant To-fung Leung, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Associate Consultant Sze-luen Chan, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Associate Consultant Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinic, Kowloon Central Cluster. L A Tse, PhD (Public Health), PgDOHY, MHKIOEH Associate Professor King-hong Chan, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Consultant and Chief of Service Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinic, Kowloon Central Cluster.

Correspondence to : Dr Catherine XR Chen, Department of Family Medicine &

GOPC, Room 807, Block S, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 30 Gascoigne Road, Kowloon, Hong

Kong SAR.

References

|

|