March 2014, Volume 36, No. 1 |

Discussion Paper

|

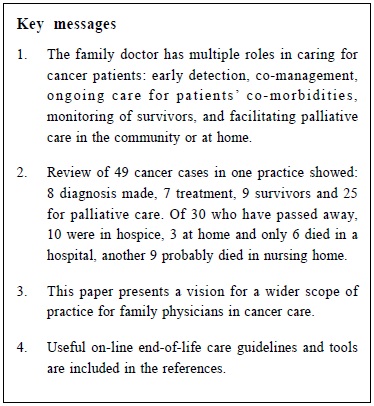

Care of cancer patients in the community: A family physician’s perspectiveCynthia SY Chan 陳兆儀 HK Pract 2014;36:24-30 Summary This paper highlights the roles of the family doctor in caring for cancer patients in the community: from early detection of the cancer, co-management of the patient together with the oncology team, integrated and collaborative primary care for patients’ other co-morbidities, to monitoring of patients who have recovered, or facilitation of palliative care at home. These roles will be illustrated with sharing of practical clinical experience. Various patient management skills and system supports required for provision of such services are also covered. 摘要 本文重點討論家庭醫生在社區照顧癌症病人的多重角色:從癌症的早期診斷、與腫瘤科團隊合作治療患者、為對患者的其他相連病症提供綜合基層治療,到對治癒者病情進行監察、或協調居家紓緩治療。透過分享實際臨床經驗說明上述不同角色,並指出提供該等服務所需的各種病人管理技巧及支援體系。 Introduction The family physician has many important roles to play in supporting a patient along his/her journey with cancer: from prevention, early detection, investigating symptoms, making diagnosis, counselling about referral and treatment options, follow-up and monitoring of those who are in remission, to treating various co-morbidities, and finally supporting the patient through end of life and the family in bereavement and beyond. Our entry point to this journey may vary, depending on where the patient begins to consult us along the course of illness, but the goals of providing holistic care, support and guidance to the patient and family in order to reduce mortality and morbidity and improve quality of life, remain the same. This paper is a summary of a presentation made at the Hong Kong International Cancer Congress in November 2012. During the presentation, videotapes of patients were shown for illustration, along with sharing of clinical experience. Patients’ identities are kept anonymous and their permission was obtained for case presentation. Author’s practice During preparation for the Congress, I conducted a retrospective analysis of my practice to identify the number and types of cancer patients and the services that I was able to provide. I have been working in a public community health centre which contains the offices of the home-care nurses, case managers and allied health-care providers. The mandate of the primary care clinic at the centre is to serve those with complex multiple co-morbidities or disability, or the marginalised vulnerable population. Our clients are multi-ethnic and ranged from newborns to 103 years. From the cancer patient registry that I kept, I had the opportunity in the past 6 years to care for a total of 49 patients with cancer at various stages of their journey. They made up about 5% of my family practice patients. Patients with only cervical atypia or pap smear abnormalities such as CIN I to III were not included in this analysis since they may only be seen once at the screening pap smear clinic. Patients with localised skin cancers were also not included as I did not keep a record of them. These 49 patients’ age ranged from 25 to 90 years at presentation, with 21 (43%) of them over 65 years old. 38 (77%) were female. There were 23 Caucasians (46.9%), 16 Chinese, 9 others (Philippino, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, South Asian, etc) and one, a local native. Lung cancer was the most common (n=13), followed by breast cancer and gastrointestinal cancer (colorectal, stomach, liver and pancreas), haematological cancers and other cancers (see Table 1). 32 of them had metastases, some up to 3 sites. Twenty-five (51%) patients were referred to me by community nurses for palliative care. Seven were still undergoing treatment and nine were cancer survivors when they first presented. Another eight had their cancers diagnosed after they became my patient. I had to make regular home visits on 12 and visited nine in hospital or hospice. The rest were seen as regular patients at the clinic. Six required home oxygen and 14 required opioids for pain control or dyspnoea. In early November 2012, 19 were still alive, with 5 of them being palliative. Of those who had passed away, six died in hospital, 10 in hospice, 3 died at home, and 2 died in another city or country. Another 9 had been transferred to nursing homes and were no longer under my care, so I had no information on their current status or where they may have died. (Table 1) The cumulative proportion of my palliative patients passing away in a hospice was 10 out of 30, i.e. 33%. The Vancouver figure was 236/1561 i.e. 15% for 2011.1 Diagnosing cancer in Vancouver Family physicians in Vancouver may order many investigations, and thus able to make diagnosis and do some staging while patients were waiting to be seen by the specialists. Examples of investigations available included ultrasounds, mammograms, nuclear medicine scans and more elaborate blood and urine tests compared to what were available to the public general outpatient clinics when I worked in Hong Kong. CT scan and MRI are also accessible. We may also request for ultrasound guided aspiration and/or biopsy of breast and thyroid lumps to be performed by community or hospital radiology departments. Waiting time for endoscopy maybe long because patients had to first be referred to the specialist for assessment. A young patient in her early twenties had early diagnosis and curative surgery for thyroid cancer. It was diagnosed by outpatient ultrasound-guided biopsy. She presented with a tiny self-discovered neck lump. Another young man, T, in his twenties was not so lucky. He was referred to me after his stomach cancer surgery. He had a 2-year prior history of dyspepsia for which he had made many doctor-visits. When he eventually had gastroscopy, he was already found to have stomach cancer. The diagnosis of lung cancer was more subtle. Chest X-ray was not useful in the early diagnosis of lung cancer.2 One new patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) had a 2-year history of back pain requiring narcotic analgesics. She had refused investigations after a previous admission in the past. Eventually she agreed to try quitting smoking and went for more tests. Her chest X-ray showed COPD and bone scan was normal. While waiting for computed tomography (CT) lung scan as an outpatient, she was admitted to hospital for COPD exacerbation. An expedited CT showed lung cancer. Another smoker, X, who was a lung cancer survivor of 7 years, complained of prolonged hoarse voice after a cold. She had a normal chest X-ray while in hospital for COPD. But she was found to have vocal cord paralysis and a subsequent outpatient CT showed recurrent lung cancer. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery 2012 guidelines recommended annual lung cancer screening with low-dose CT for North Americans from 55-79 years with a 30 pack-year history of smoking, and annual low-dose CT for long-term lung cancer survivors until age 79.3 In contrast, colon cancer in another patient, Y, was diagnosed early. She had a mild drop of haemoblogin. On questioning, this 88 year old lady with long-standing diabetes and heart failure, did have some recent “haemorrhoid bleeding”. She was taking an anti-platelet after a vascular surgery for foot gangrene. Differential diagnoses included bleeding from medication and haemorrhoids. However, colo-rectal cancer had to be ruled out in the elderly with anaemia. Colonoscopy revealed colon cancer, and she had laparoscopic hemi-colectomy. Videotapes of both patients (X and Y) were shown during the presentation to demonstrate the importance of keeping alert while following-up patients with multiple chronic diseases, and in particular cancer survivors. Co-management with specialists and comprehensive care for co-morbidities While some patients attend mainly the BC Cancer Agency for follow-up when they are receiving radiation, chemo- or other therapies, many would also return to the family doctor for continuing management or for other medical problems. In rural areas, general practitioner (GP) champions who participate in the BC Family Practice Oncology Network4 may administer the chemotherapy and co-manage the cancer patient with the oncology team. In a qualitative study of 15 US family physicians and their cancer patients, the doctors described their roles as: coordinating referrals, providing general medical care, helping with decisions and providing emotional support. Their patients valued “clear explanations and spending time with and feeling comfortable with their family physicians.5” This involvement was more intense at the time of cancer diagnosis and near death. Although the above patients X and Y were referred to the cancer specialists or surgeon for management, I continued to follow them up for emot iona l suppor t and cont inuing care of their multiple medical problems. The oncologist sent a reminder for Y’s one-year follow-up colonoscopy. Y celebrated her 90th birthday two years after her cancer surgery! Family physicians may be better able to understand and communicate with the patient to facilitate adherence to treatment. For example, a patient with end-stage lymphoma who had refused chemotherapy was referred to me for palliative care. She was afraid she would get too sick from the treatment, despite evidence that her lymphoma had a good chance of improvement with therapy. When she later became very weak and dypnoeic, she finally agreed to be admitted to the palliative ward for pleural effusion drainage. I visited her in the hospital and gave her a book entitled: 90 minutes in Heaven6, and encouraged her to reconsider her decision. She eventually consented to give chemotherapy a try. She survived for another 6 months, with much improved quality of life, and was able to finish writing her book. Timely communication between cancer specialists and family physicians is very important, as is the channel for quick consults and admission to hospital for emergencies. The BC Cancer Agency and the specialists send consult and progress reports to keep us updated on patients’ diagnosis, management and follow-up plans. For a homebound palliative patient who was suffering from diffuse herpes ulcers while on high dose dexamethasone post-radiotherapy, a confirmatory telephone call from the oncologist about my diagnosis and treatment was reassuring to me and the patient’s family. Some patients may come to us to discuss non-medical issues such as whether they were safe to fly or not, as some were immigrants and would like to settle their personal affairs back in their home country before they die. One was fortunate and was able to fly back and forth twice, despite having had radiotherapy for spinal metastasis, while another one flew back to die in his home country against his family’s wishes. Cancer diagnosis and management is only one of the many aspects that the family physician has to take care of for patients with multiple co-morbidities. In fact, 32 (65%) of my patients also had one or more chronic diseases: such as hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, COPD, stroke, atrial fibrillation on warfarin, arthritis, peptic ulcer, etc that required ongoing care. Palliative care and home deaths When patients in Vancouver have end-stage illness with life expectancy of six months or less, family physicians can complete a BC palliative care benefit application form for them if they fulfill the eligibility criteria. This will cover medication and equipment costs and home care support. There was a recent campaign for family doctors to engage patients and bring up the issue of advance directive. However, when patients were referred to me for palliative care, “Do not resuscitate” and end-of-life discussions had often been initiated by the oncologist team already. My role was then to clarify with the patient and family that although the specialists may have stopped treatment or only provided palliative treatment, much more could be done to relieve pain and discomfort. The patient was encouraged to keep a balanced perspective of getting ready and preparing for the worst yet remaining hopeful, because life is not in the doctors’ hands. There is actually evidence to show that patients who are started on palliative care early may live longer than those who are not.7 At least 4 of my palliative patients had lived for longer than one year. The family physician’s job is to walk this journey with them, be available to provide holistic care in collaboration with the community nurses, palliative nurses, pharmacist, case manager, and others when required (e.g. clergy, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, dietitian, home care workers), and seek advice from home hospice physicians when indicated. To guide the family physicians and nurses in the assessment and management of the various symptoms of pain, dysponea, nausea and constipation, etc, our Health Authority has produced a handbook on palliative care. The BC palliative care guidelines8 have also been developed and posted on the internet. There is a PAL (palliative access) telephone hot-line for consulting with a hospice physician and for referral to palliative care wards or hospice, should the patient not prefer to die at home. For those who desire home death, there is a “notification of expected death at home” form that the doctor can sign. Patient will not be taken to the hospital, and the body after death can be picked up directly by the funeral home. Patients can be monitored by homecare nurses for 72 hours prior to death and terminal medications are provided in a locked medication kit8 for the nurse to administer parenterally if needed. I had the opportunity to witness two opposite examples of home death: one very peaceful due to good preparation, while the other one very traumatic due to denial and lack of preparation. The first case was well prepared with a family conference that involved the whole family, the hospice physician and resident, me, the family doctor, the palliative nurse, the social worker, a translator and their pastor. The patient had nursing support at home in her last 72 hours and died peacefully in the night. The nurse was there to support the family and pronounce the death. I was notified by phone and the funeral home was called. I completed the death certificate at the office the next day. On the other hand, the other palliative Chinese patient died suddenly at home but her family was totally unprepared. They did not even have our clinic’s telephone number on hand, despite having had a few discussions about her poor prognosis and various end-of-life care options. My third videotape was an interview of a Chinese patient who had referred her mother to my care in the last phase of the mother’s cancer. She described how we walked that journey together and the support she got. As the cancer progressed, she eventually had difficulty looking after her mother at home, but was relieved that her mother would now be in heaven because a chaplain friend of mine visited her at the hospice. In the film, she eagerly urged doctors to be present for their terminal patients and their family, who will then be more willing to open up their hearts to their care. Vancouver is a city with many immigrants. There is the occasional traditional Chinese or South Asian client who may not be willing to discuss advance directives or palliative care. But denial of cancer diagnosis is definitely not unique to the Asian culture. Care of cancer survivors Not all patients succumb to cancer. With the advance in screening, diagnosis and treatment of many cancers, we now see more cancer survivors in primary care. Our expanded role would be to monitor cancer survivors for long-term complications of cancer treatment, in addition to cancer recurrence. Patient X was fortunate and had responded to radiotherapy for her recurrent lung cancer. Another cancer survivor developed recurrent abdominal pains with abnormal liver function. Fortunately, these were found to be due to common duct stone obstruction and a medication rather than a recurrence of lymphoma. Patients may be affected by the psychological aftermath of their cancers. The young man, T, was still suffering from anxiety even after he had survived his stomach cancer. Patients with past history of cancer may also develop other illness and die from non-cancer causes. We need to offer them comprehensive preventive care for medical illnesses for which they may be at risk. Some younger patients who recovered from their cancer may also need counselling about contraception and pregnancy. Knowledge and skills, and support required in cancer care In Vancouver, I did not have a large number of cancer patients, but I was able to do more for them. Palliative care and narcotic prescription were new to me, but there were guidelines8 to follow, opportunities to learn and resources for support. I was able to gain experience in managing palliative patients in their home. One highlight was to be able to take a family practice resident doctor on palliative home-visits. We went through with the family about options of hospice or home death, and completed the necessary documentations. He became so excited when the bed-bound patient whom he thought was dying soon, actually improved and was still alive and able to sit up, when he visited again on the third time a few months later! Although we aim to provide comprehensive continuing care to all our patients, many family physicians in Hong Kong may not have the opportunity to assume their multiple roles in cancer care, other than screening and diagnosis. Once patients are diagnosed with cancer and referred, family physicians seldom get to see them again. Without support, many family physicians may not see themselves engaging in the roles of cancer staging, co-management or palliative care. This paper aims to illustrate the extent of the role a family doctor can play in the community in terms of cancer care, and presents a vision for a wider scope of family practice. Family physicians that look after cancer patients will require regular updates of their knowledge in cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment. They should use a comprehensive approach, and practice empathic communication and counselling. Ideally, their practice needs to be organized9 to facilitate regular monitoring and recall of patients for screening and follow-up according to guidelines. Collaboration with other healthcare providers is also essential. The extent of the scope of the family physicians’ practice will also depend on the willingness of the health care system to include them in the delivery of cancer care. As the population ages and there are more initiatives and greater need for palliative care in the community, this may be an opportune time to explore a structured community palliative programme for family medicine trainees with placements at palliative units and palliative home-visits, clinical oncology and surgical oncology outpatient clinics and genetic-oncology counselling service. A more extended elective for the senior family medicine trainee can also be considered. Examples of continuing educational updates in BC include free monthly webinars (seminars broadcasted on line) held by the BC Family Practice Oncology Network, as well as an annual conference for family physicians who are interested in cancer care. There are also clear guidelines and protocols available on the Cancer Agency website.8,10 An end-of-life practice support learning programme11 has recently been developed. Family physicians are paid to attend three evening learning sessions over the course of several months, with action periods in between to apply the materials and tools learnt in their practice. There needs to be some incentive in the health care system to compensate for the extended encounter time required for discussion about making advance directives and end-of-life care plans, and helping patient and family come to terms with when to stop active treatment and contemplate death outside of a hospital. This latter culture change is required, before any change in legislation, for successful implementation of choosing home deaths. Finally psychological support for debriefing may be required as it can be emotionally intensive for the family doctor to look after dying patients and their caregivers.12 Conclusion As a family physician, I am able to provide more continuing and comprehensive care to cancer patients in Vancouver compared to when I worked in Hong Kong. There are more supports and home care back-up. The structure for palliative primary care and home deaths is better established. With more training and supports in the health care system, family physicians in Hong Kong can also contribute more to the care of cancer patients in the community. Their patients will benefit from the collaboration between oncologists, cancer centre, family physicians and community nursing.

Cynthia SY Chan, MD (Manitoba), FCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Correspondence to: Dr. Cynthia Chan, 410-2775 Heather Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V5Z 1M9. E-mail: Cynthia.chan1@vch.ca References

|

|