March 2014, Volume 36, No. 1 |

Original Article

|

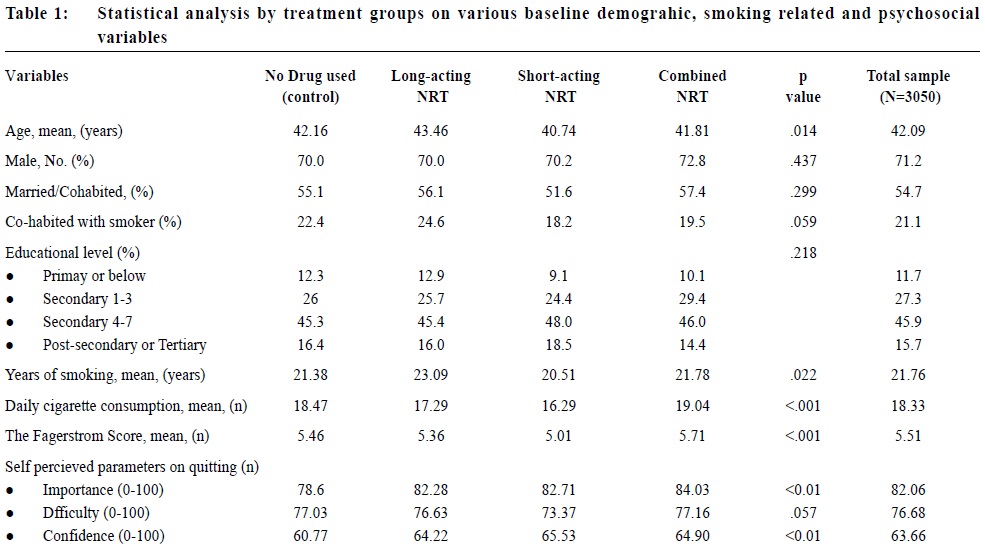

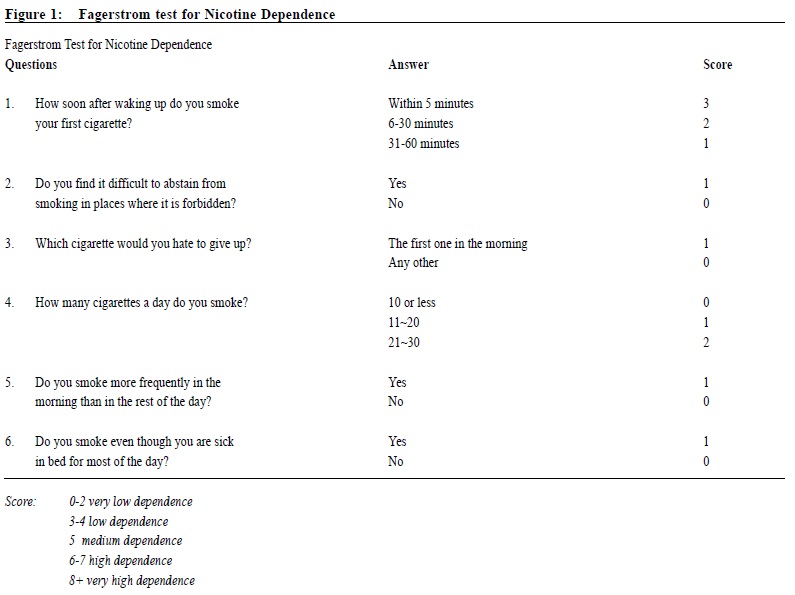

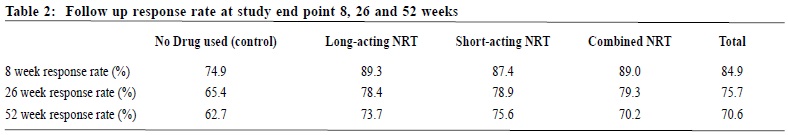

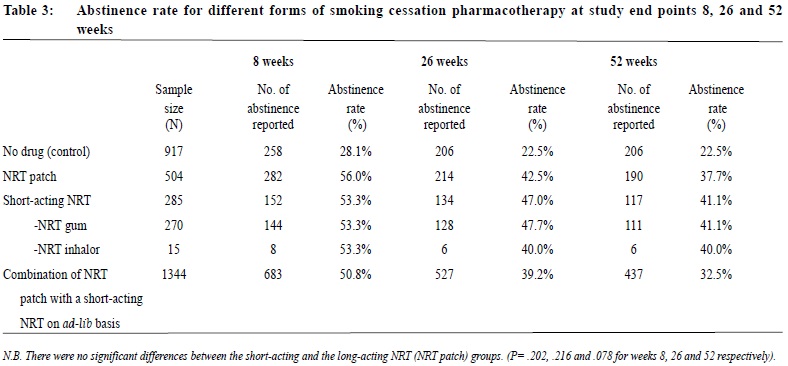

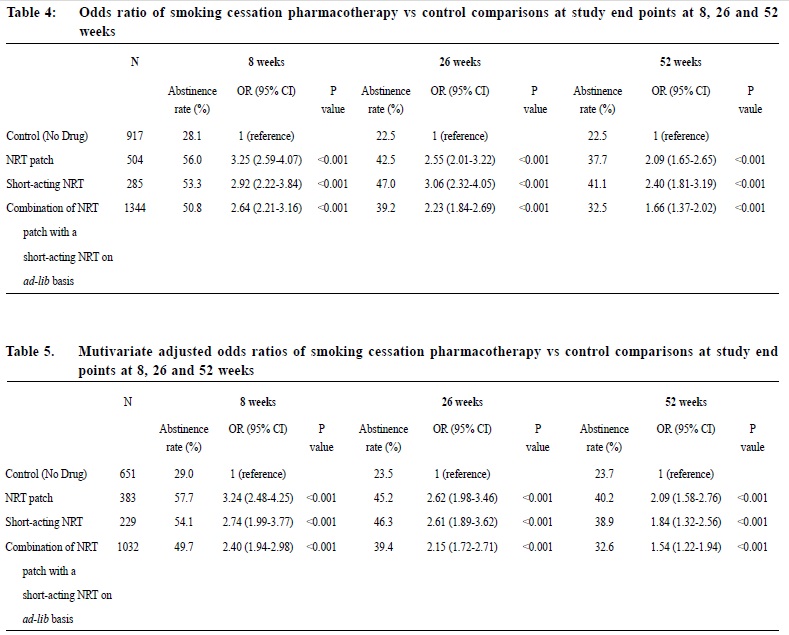

Observational study on the efficacy of various modalities of Nicotine Replacement Therapy available in Hong KongAmbrose CH Wong 王智康, Kin-sang Ho 何健生, Kam-wing Ching 程錦榮,Helen CH Chan 陳靜嫻, Marget FY Wong 黃鳳儀 HK Pract 2014;36:4-10 Summary Objective: This study aimed to provide and compare the qui t rates of di f ferent modalities of Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) in Hong Kong. Design: A retrospective cohort study. Subjects: 3,050 smokers aged 18 or above, who visited the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Integrated Center on Smoking Cessat ion (TWGHs ICSC) for smoking cessation interventions during the period of 01/01/2010 to 31/12/2011. Main outcome measures: Different forms of NRT prescr ibed at the ini t ial visi t were ident i f ied and corresponding quit rates calculated by means of self reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 8, 26 and 52 weeks. Results: The self reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 8 weeks, 26 weeks and 52 weeks were 56.0%, 42.5% and 37.7% for quitters using NRT patch monotherapy, 53.3%, 47.0% and 41.1% for clients using NRT short-acting monotherapy and 50.8%, 39.2% and 32.5% for those using combined NRT therapy respectively. Multivariate adjusted odds ratios (OR) at 8, 26 and 52 weeks were 3.24 (95% CI, 2.48-4.25), 2.62 (95% CI, 1.98-3.46) and 2.09 (95% CI, 1.58-2.76) for NRT patch monotherapy; 2.74 (95% CI, 1.99-3.77), 2.61 (95% CI, 1.89-3.62) and 1.84 (95% CI, 1.32-2.56) for short acting NRT monotherapy; 2.40 (95% CI, 1.94-2.98), 2.15 (95% CI, 1.72-2.71) and 1.54 (95% CI, 1.22-1.94) for combined NRT respectively. Conclusion: Various treatment modalities of NRT available in Hong Kong are effective in increasing abstinence rate of smokers who were prepared to quit. Keywords: Nicotine replacement therapy, smoking cessation, Hong Kong, efficacy 摘要 目的:本研究旨在提供並比較在香港採用各種尼古丁替代療法(NRT)的戒煙率。 設計:回顧性隊列研究。 研究對象:2010年1月1日至2011年12月31日期間到東華三院戒煙綜合服務中心接受戒煙治療的3,050名18歲或以上吸煙者。 主要測量內容:確定吸煙者初診時所用的尼古丁替代療法,並從自我報告中在第8、26和52周時點的7天戒煙率計算出相應戒煙率。 結果:自我報告的第8、2 6和5 2周時點的7天戒煙率分別為:尼古丁戒煙貼,56.0%、42.5%和37.7%;短效尼古丁替 代療法,53.3%、47.0%和41.1%;尼古丁合併替代療法,50.8%、39.2%和32.5%。第8、26和52周的多變數調整後比值比(OR)分別為:尼古丁戒煙貼,3.24(95% CI:2.48-4.25)、2.62(95% CI:1.98-3.46)和2.09(95% CI:1.58-2.76);短效尼古丁替代療法,2.74(95% CI:1.99-3.77)、2.61(95% CI:1.89-3.62)和1.84(95% CI:1.32-2.56);尼古丁聯合替代療法,2.40(95% CI:1.94-2.98)、2.15(95% CI:1.72-2.71)和1.54(95% CI:1.22-1.94)。 結論:在香港所用的各種尼古丁替代療法均可有效地提高有志戒煙者的戒煙率。 主要詞彙:尼古丁替代療法,戒煙,香港,功效 lntroduction Smoking is a major public health issue in Hong Kong. In 2010, 657,000 people aged 15 or above (about 11.1% of the entire population) were smokers.1 A local study suggested that about half of Hong Kong’s Chinese persistent smokers will eventually be killed by tobacco.2 Quitting smoking has immediate as well as long-term benefits, reducing risks of diseases caused by smoking and improving health in general.3 Over the past decades, tremendous efforts have been made by the Hong Kong Government to reduce local smoking prevalence and protecting its residents from harms related to tobacco. With reference to the ‘MPOWER’ measures introduced by the WHO4, various programmes were commenced to provide interventions for smokers in Hong Kong to cease smoking. In January 2009, Tung Wah Groups of Hospitals Integrated Center on Smoking Cessation (TWGHs ICSC) was commissioned by the Government’s Department of Health to undertake a pilot project for smoking cessation by providing both pharmacotherapy and counselling services. As at April 2013, 8 centres are located in different districts in Hong Kong to provide individualized and professional smoking cessation service. Various forms of smoking cessation medications including Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) as well as Non-NRT have been proven to be effective in increasing abstinence rate of motivated smokers.5-7 Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is one of the most commonly used smoking cessation medication. It does not increase cardiovascular risk in patients with underlying stable cardiovascular disease and can be used by motivated smokers if under medical supervision.8-11 Five NRT products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Four of them are short-acting (nicotine gum, nicotine nasal spray, nicotine inhaler, nicotine lozenges) and the other is long-acting (nicotine patches). In Hong Kong, three types of NRT products were available in the market during our study period. The nicotine patch and nicotine gum were available as over-the-counter (OTC) products, while nicotine inhaler was available as a prescription drug. Overseas controlled trials have concluded that all commercially available forms of NRT can increase long-term quit rate by 50-70%.5 Some studies also suggested that using a combination of NRT products (nicotine patch and an ad libitum NRT) was better than one NRT product alone.7,12 Local data on the effectiveness of NRT are lacking. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of different treatment modalities with NRT in a real life setting within our locality. Methods Case records in the study period were reviewed and analysed. Participants Case records of all smokers who visited TWGHs Integrated Center on Smoking Cessation (ICSC) for smoking cessation interventions between 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2011 were reviewed. Access to the ICSCs included the Department of Health’s smoking cessation quit line, self referrals or external referrals (such as dentists, general practitioners). Clients aged below 18 years old or with non-NRT medications prescribed were excluded from the study because the sample size for non-NRT user was too small. Clients were allocated to 3 intervention arms, namely single long-acting NRT (NRT patch) group, single short-acting NRT (NRT gum or NRT inhaler) group and combined NRT group (NRT patch plus NRT gum or inhaler) according to the type of pharmacotherapy prescribed at the initial visit. Those not receiving pharmacotherapy of any kind were assigned to the control group. Medication interventions The formulations of NRT available in TWGHs ICSC during the study period included nicotine patches (21mg/24hrs, 14mg/24hrs, 7mg/24hrs, 15mg/16hrs, 10mg/16hrs and 5mg/16hrs), nicotine gums (2mg and 4mg) and nicotine inhaler (10mg). The form of NRT provided was determined by client’s preferences after thorough explanation. Overall treatment course varied from 8 to 12 weeks depending on patients’ needs. NRT was issued by doctor for those with medical problem or if nicotine inhaler was being used; NRT would be issued by counsellor for those without medical problem and if non-prescription NRT was being used. Smoking cessation counselling Registered social workers provided individual smoking cessation counselling to all clients once weekly for the initial two weeks and then once every two weeks. All counsellors had been trained in tobacco cessation counselling. Motivational interviewing technique13,14 was adopted in the counselling session. Outcomes As part of the programme, clients’s smoking status was reviewed by face-to-face or telephone interview at 8, 26 and 52 weeks. Outcome measure was the 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate of smokers at 8, 26 and 52 weeks based on intention to treat analysis. Those who were lost to follow up or with unknown smoking status will be considered as not quitted smoking. Statistics Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0. Baseline characteristics of participants were summarized by means, frequencies and percentages. Independent T-test and chi-square test were used to investigate the differences between means and proportions in basic characteristics among participants receiving different modes of pharmacotherapy. Intention to treat analysis and logistic regression model were used to identify the relationship between mode of pharmacotherapy and abstinence at 8 weeks, 26 weeks and 52 weeks. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to determine the cross-sectional relation between mode of pharmacotherapy and abstinence status. Potential confounding factors such as socio-demographic data, smoking history, cohabited smoker, perceived importance, difficulty and confidence of quitting were adjusted in the analysis. Statistical tests were performed at the 5% level of significance. All estimated effects were accompanied by 95% confidence intervals, where appropriate. Written consents to collect personal data were obtained at the first intake of service users. Since this was a retrospective case review study, those providing treatment were essentially blinded to the study. Results 3,107 smokers visited TWGHs ICSC for smoking cessation intervention within the study period. 57 records were excluded because the inclusion criteria were not met. Demographic details are shown in Table 1. The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day was 18.3 and the mean Fagerstrom Score (Figure 1) was 5.51. 2,133 (69.93%) received smoking cessation pharmacotherapy plus counselling, while the remaining 917 (30.07%) received counselling on smoking cessation only. Among NRT users, 504 (23.63%), 285 (13.36%) and 1,344 (63.01%) received patch, gums or inhalers, and combined-NRT therapy (combination of NRT patch plus a short-acting NRT, either gum or inhaler on ad libitum basis) respectively at initial visit. The follow up response rate (percentage of those being successfully contacted for follow up) at study end point 8, 26 and 52 weeks were 74.9%, 65.4% and 62.7% for control group, 89.3%, 78.4% and 73.7% for long-acting NRT group, 87.4%, 78.9% and 75.6% for short-acting NRT group, 89%, 79.3% and 70.2% for combined NRT group (Table 2). The self reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 8 weeks, 26 weeks and 52 weeks were 56.0%, 42.5% and 37.7% for patch monotherapy, 53.3%, 47.0% and 41.1% for short-acting monotherapy and 50.8%, 39.2% and 32.5% for combined therapy respectively. In the short-acting monotherapy group, the self reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 8 weeks, 26 weeks, and 52 weeks were 53.3%, 47.4% and 41.1% respectively for gum, and 53.3%, 40.0% and 40.0% respectively for inhaler (Table 3).     The odds ratio of abstinence rate of pharmacotherapy versus control comparisons showed that all treatment groups produced higher abstinence rate at all study end points than control (Table 4). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed the difference remained statistically significant after adjusting for confounding variables. Multivariable adjusted odds ratios (ORs) at 8, 26 and 52 weeks were 3.24 (95% CI, 2.48-4.25), 2.62 (95% CI, 1.98-3.46) and 2.09 (95% CI, 1.58-2.76) for long-acting NRT monotherapy group; 2.74 (95% CI, 1.99-3.77), 2.61 (95% CI, 1.89-3.62) and 1.84 (95% CI, 1.32-2.56) for short acting NRT monotherapy group; 2.40 (95% CI, 1.94-2.98), 2.15 (95% CI, 1.72-2.71) and 1.54 (95% CI, 1.22-1.94) for combined NRT group respectively (Table 5). The variables included in the multivariate logistic regression model were age, gender, cigarettes consumption per day, years of smoking, marriage status, educational level, Fagerstrom score, the presence of cohabited smoker, and perceived importance, difficulty and confidence on smoking cessation.  Discussion We are not aware of any large scale studies which evaluate the various forms of NRT for smoking cessation in Hong Kong. This observational study provides evidence from a real life situation that nicotine replacement therapy increases abstinence rate for up to 52 weeks after initiation of treatment when compared to counselling and behavioural support alone. As previously mentioned, we did not include non-NRT in our study due to small sample size of 17 for bupropion group and 88 for varenicline group. A study done by Jean-francois Etter and John A. Stapleton commented that the relative efficacy of a single course of NRT remained constant over many years.15 Further studies with longer follow ups are required to assess if the same applies in our local setting. Similar to existing literature, our study showed that the available types of NRTs resulted in similar abstinence rates. On the other hand, our study failed to replicate the superiority of combined NRT over monotherapy, as suggested by previous randomised studies.5,16 It is probably due to the fact that in these overseas studies, the study population were randomised; subjects usually smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day and many studies excluded patients who suffered from psychiatric diseases such as schizophrenia and depression. Strength and limitations of study Our study was a large scale study on the use of NRT in Hong Kong. There were several limitations in this study. First of all, this study was an observational retrospective study and was not a randomised control trial on various forms of NRT. Data of potential confounding factors such as co-existing medical illnesses like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, mental disease and number of previous quit attempts were not collected. In addition, participants were not randomised into different intervention arms and control group. Finally, self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate was used as the outcome measurement in this study, which was not biochemically validated. This might potentially overestimate abstinence rates. However, the sample of our study came from all walks of life and most of them were self motivated to quit smoking either by self referral and external referral. The service provided by TWGHs ICSC was free, well publicised and easily assessable for all residents of Hong Kong. Hence, we believe that our participants can reasonably represent the motivated smokers in Hong Kong.  Conclusion This study has shown that various forms of NRT commercially available in Hong Kong are effective in increasing cessation rate of motivated smokers. NRT combined with counselling should be considered as one of the options for smoking cessation unless contraindicated. Acknowledgement We are thankful to Mr. Choi Wa Chi, counsellor of ICSC TWGHs, for his assistance on statistical analysis. Ambrose CH Wong, MBChB, MFM (Monash University), Dip. Med (CUHK)

Medical Officer TWGHs Integrated Center for Smoking Cessation Kin-sang Ho, FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKAM (Medicine) Kam-wing Ching, MBBS, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Helen CH Chan, M Soc Sc, BSW Marget FY Wong, M.A., M Soc Sc, BSW Correspondence to: Dr Ambrose CH Wong, TWGHs Integrated Center for Smoking Cessation, 17/F, Tung Sun Commercial Centre, 194-200 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong SAR. References

|

|