|

March 2017, Volume 39, No. 1

|

Update Article

|

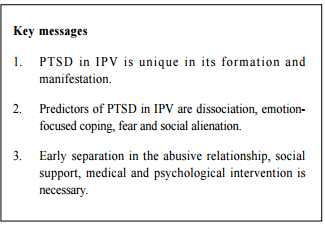

Post traumatic stress disorderConnie LW Chan 陳麗華 HK Pract 2017;39:14-18Summary Intimate partner violence (IPV) is not uncommon and it takes a toll on both the physical and mental health of the victims, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prominent health issue. IPV-related PTSD has its unique features in formation and manifestation, but is nevertheless debilitating and dysfunctional. A case of PTSD of IPV is reported, and the various treatment modalities are discussed. Social and practical support, medication and psychological intervention are of great importance in breaking the viscous cycle of staying in the abusive relationship and perpetuating the PTSD symptoms. 摘要 親密伴侶暴力(IPV)並不罕見,往往會造成受害伴侶身體和心靈的創傷,創傷壓力症候群是其中比較突出一項。IPV引發的創傷壓力症侯群的發生與表現都有著其獨特之處,造成受害人生活失衡以及應變能力大大削弱。作者引述本地案例,闡述現有治療模式,強調要透過社會和實務性的支援,並加上藥物和心理治療方可見 效,使受害者打破暴力的惡性循環和去除創傷壓力症候群表現。 Case vignette Ms C, a 39 year old mother of two, was referred to the psychiatric outpatient clinic from the Integrated Mental Health Program of Family Clinic for low mood, irritability, poor sleep, and fleeting suicide idea after the delivery of her first child. She was diagnosed to have postnatal depression. Albeit she had adequate treatment of antidepressants, she had prominent anxiety symptoms. She gradually disclosed details about her husband’s illicit drug problem, and about her repetitive pushing and clashing with him that had exacerbated her joint pains. It was not an easy decision to separate herself from her husband as they had to raise a son together, but she eventually made it after a serious physical encounter in which she was hit on the head with a guitar by him. However, the aggression perpetuated, despite separation. She became pregnant again by a non-consensual sexual intercourse while they were separated. Her husband kept on threatening her safety in his visitation with their two children. One day, he forcibly entered her apartment and poured faeces onto her to deter her from filing divorce. She felt disgusted and manifested with full-blown symptoms of PTSD, namely intense fear, hyper-vigilance, flashbacks of the insulting act, retching, lingering sensation of foul smell and odor. Brief shortacting benzodiazepines was prescribed on top of her antidepressant, psychological intervention, re-allocation of abode, a restraining order to refrain her husband from contacting her and their children, social support and practical help for childcare. Eventually, her PTSD symptoms gradually resolved after 5 months. Intimate partner violence (IPV) Family physicians and AED doctors are probably the professionals that victims of IPV would first turn to, before seeking help from social workers1 or police, for obvious health reasons. The above case illustrates how IPV can harm a battered partner’s physical, as well as mental health. The spouse-perpetrator continued to intimidate the victim even though they might be physically separated, due to relationship commitments, that is, being married and having common children. The abused victim would hence find it harder to get out of the relationship2 , which indirectly prolonged the duration of IPV. IPV are notoriously under-reported because of shame and ambiguous social situations (being torn between love and hate in a relationship). It causes the abused victims not to see themselves as victims, but as having hiccups in a rough relationship. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC 2010) website defines IPV as ‘physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse’.3 Psychological abuse includes name calling, threats, intimidation, financial control, abuse of children or pets, and blaming the victim.4 The severity and frequency of these domestic violence vary considerably, some being situational, some repetitive, and some pervasively and coercively controlling. Notwithstanding the variability of causes and triggers, they all harm the mental health of the victims, their relationship as partners5 , parenting quality and well being of their children.6-7 Among them all, post traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety are the most prevalent mental health sequel of intimate partner violence.8-9 In Hong Kong, there were 2471 cases of newly reported spouse / cohabitant battering cases from January to September 2016 according to the date from the Social Welfare Department10, and among them, 79.8% are physical, 0.6% sexual, 12.2% psychological and 7.4% multiple. The local data shows that 59.6% of IPV were committed by husbands, 11.3% by wife, 4% by ex-husband, and 0.7% by ex-wife. The remaining one-fifth of the cases were preyed by cohabitants and ex-cohabitants, hetero- and homo-sexual included. PTSD in IPV Dutton (2000)11 suggested that there were 4 dimensions that distinguished intimate partner violence from other traumas: firstly, there is the threat of ongoing traumatisation; secondly, repeated exposures to trauma; thirdly, history of similar trauma exposures, such as childhood physical or sexual abuse; fourthly, the nature of the relationship with the perpetrator. PTSD symptoms are not always apparent immediately after the traumatic incident, but instead can become salient months later.12 Generic risk factors for IPV include low socioeconomic status13, pregnancy14-15, young age16, and history of childhood maltreatment.17 Altered response in women with PTSD in IPV Fear is indeed an innate programme to escape from danger. It involves interpretation of stimuli being dangerous and starting a cascade of physiological activity preparatory for escape. If fear remains inaccessible by avoidance, or if the fear is interpreted in an erroneous way, it will result in catastrophic thoughts and the fear will be strengthened.18 Predictors of PTSD in IPV Dissociation IPV victims might attempt to disengage from the abusive experience by withdrawing emotionally. This allows them to report a lower pain perception despite an apparently heightened neural and physiological response.19 The higher the avoidance, the higher degree of pain attenuation. Emotional-focused coping Emotion-focused coping20 helps an individual to assuage psychological distress and reduce negative affect through positive re-appraisal or denial, but it will perpetuate the violence and abolish the motivation to escape. Fear The more a woman believes that her partner is likely to hurt her, the higher the level of PTSD symptomatology21, even though a victim’s perceptions of danger may not always correspond to the objective level of threat. Social support Alienation22 is significantly associated with more PTSD symptoms, whereas social support can act as a protective factor. Collateral damage Women with IPV-related PTSD have more physical and gynaecological problems, and also more significant impairment in bonding with their offspring. They have less effective parenting and less desirable attachment to their children, who may manifest with behavioural and emotional problems. They are found to have higher rates of internalising (e.g. depression, anxiety, PTSD) and externalising problems (e.g. aggression, behavioural problems) in boys. 23-24 Treatment of PTSD in IPV Safety and social support Removal from the IPV situations is the first step of treatment. It goes without saying that cessation of IPV will reduce PTSD symptoms. Ambivalence and distorted view in the relationship pose hurdles for them to begin treatment until much later (usually more than a year from time an IPV occurred).25 However, discussion with the women about ‘quick-escape’ plan is needed for every visit, to ensure safety and to prepare them to leave the abusive relationship eventually.

Family physicians are in the unique position to provide formal social support like referrals to medical social worker/ community nurses, support for housing needs, and for childcare problems). The rapport from family doctors is irreplaceable, it could help victims to abolish distorted fear appraisal in battered partners in the acute stress phase (less than 4 weeks after a traumatic event), and minimise the chance of the occurrence of PTSD.26-27 Reconnection of social networking28, childcare and employment are the groundwork of empowerment of the victim’s decision to start a process to change.29 Medication Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s: mainly Fluoxetine, Paroxetine and Venlafaxine)30 are the most widely studied, and the first line of medical treatment, followed by Selective Serontonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRI’s) / Noradrenergic & specific serotonin antidepressant, and then tricyclics / Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor (MAOI) / Reversible Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (RIMAs).31 Atypical antipsychotics (mainly Risperidone, Olanzapine, Quetiapine) and anticonvulsants/ mood stabilizer (e.g. Lamotrigine) could be used as adjunctive antidepressants to resistant PTSD symptoms. Medication that targets on sympathetic nervous system, e.g.α1-adrenergic anatgonist, Prazosin32, and α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, Clonidine33 (inhibits central sympathetic activity in the brain without affecting norepinephrine) also reduce nightmares and hyperarousal, startling response and intrusive thoughts. Nevertheless, none was specific for PTSD of IPV origin. Short-term benzodiazepines can reduce anxiety symptoms, but it shows no efficacy in reducing PTSD symptoms. Psychological intervention Various psychological interventions have been designed with various success in treating PTSD, depending on the expertise of the clinicians. Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) CPT for PTSD associated with IPV is currently being developed.34-35 It is a structured frame to help the clients to recognise and challenge cognitive distortions, first regarding their worst traumatic event, and then the meaning of the events and aftermath. It aims to reduce fear through guided exposure sessions. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) CBT when coupled with exposure technique, psychoeducation, breath control, self esteem training, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, planning of pleasant activities and relapse prevention can also reduce PTSD symptoms.36 Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) NICE guidelines considers equal effectiveness between eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)37; however, a Cochrane review38 showed that effectiveness of EMDR is debatable. Problems in depicting IPV Sometimes the partners would control access to money and the modes of communication of their other halves. Some would be accompanied by the abusive partner in the waiting room during their clinic attendance, and victims may well simply take a silent stance out of safety consideration. Screening of all women is not practical and its efficacy is debatable39 but gentle tapping on their view about their relationship in an open question should be encouraged. Clinical suspicions should be raised if the women have hesitation in answering or when irregularities are spotted, for example, repeated delayed medical treatment, unexplained injury, unexplained physical problems, e.g. headache, dizziness, chest pain, palpitation, back pain, nausea and indigestion, stomach, pain, menstrual/ pelvic pain40, then pursuit inquiry about IPV would be necessary, and it should be done in a safe and private setting. Other adults known to the woman and children should be ideally excused from the room prior to inquiry about IPV. Conclusion IPV takes a toll on the general physical and mental health of the victims. PTSD related to IPV is different from other traumas that the perpetrator and the victim are intimately involved, and such relationships put the victim in repeated situation of ongoing aggression and fear. The fear of violence or fatality can be incongruent to the actual level of violence, and the symptoms of PTSD may not be apparent right after an episode of aggression. Battered spouse with prior exposure to trauma (e.g. childhood abuse), more commitment to the relationship, avoidance of shame and coping strategy of emotion-focused origin are likely to remain in the abusive relationship longer, and thus having a higher risk of developing PTSDs. Removal to a place of safety is the first step in treating PTSD in IPV. Social support is salient to empowering the victims with the ability to make the most appropriate choice. Medication (namely SSRI, atypical antipsychotics, and medication targeting sympathetic attenuation) and combination of psychological intervention are likely to be needed. Early intervention hopefully can reduce the emergence of PTSD in the victims and collateral damage in their offspring.

Connie LW Chan, MB ChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych Correspondence to: Dr Connie LW Chan, Yung Fung Shee Psychiatric Centre, 2/F, Yung Fung Shee Memorial Centre, 79 Cho Kwo Ling Road, Lam Tin, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. E-mail: clw214@ha.org.hk

References

|

|