|

September 2017, Volume 39, No. 3

|

Original Article

|

The prevalence and associated factors of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese hypertensive patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus - A cross sectional study in 3 primary care clinics in Hong KongMichelle SS Fu 符小颯,Loretta KP Lai 黎潔萍,Pang-fai Chan 陳鵬飛,Kai-lim Chow 周啟廉,Matthew MH Luk 陸文熹,David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2017;39:67-76 SummaryObjectives: To evaluate the prevalence and associated factors which contribute to the development of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. Design: A cross sectional study. Subjects: All Chinese hypertensive patients who were followed up at the participating clinics and developed new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus from 1st January 2012 to 31st December 2012. Main outcome measures: Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes. The associated factors of developing diabetic retinopathy.

Results: 289 patients were included during the study period. 37.4% had background diabetic retinopathy in which 2.8% had maculopathy. No statistically significant association was observed between diabetic retinopathy and some known associated factors such as poor diabetic control and high blood pressure. Conclusion: In our study, more than one-third of the patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus were found to have diabetic retinopathy upon diagnosis, which was higher than that reported in the general diabetic population locally or internationally. This might be explained by the fact that our selected group of hypertensive patients was a known risk factor of diabetic retinopathy. In view of the high prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and no associated factors were identified, early diabetic retinopathy assessment is important in this group of patients for timely detection and intervention. Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, risk factors, Chinese,hypertension, primary care 摘要目的:評估新發二型糖尿病的華人高血壓患者糖尿病視網膜病變的患病率及致病的相關因素。 設計: 橫斷面研究。 研究物件:2012年1月1日至12月31日期間, 在參與診所複診的新發II型糖尿病華人高血壓患者。 主要測量內容:新發二型糖尿病的華人高血壓患者糖尿病視網膜病變的患病率。糖尿病視網膜病變致病的相關因素。 結果: 共有289例患者參與研究。發現37.4%的患者已出現\糖尿病視網膜病變,其中2.8%的人有黃斑病變。糖尿病視網膜病變與糖尿病控制不佳、高血壓等一些已知相關因素之間 ,未發現存在有統計學意義的關聯。

結論: 超過三分之一的二型糖尿病新發病例,患有糖尿病視網膜病變,高於本地或國外報告的普通糖尿病人群。其原因可能是我們選定的高血壓患者人群是糖尿病視網膜病變的已知危險因素之一。鑒於糖尿病視網膜病變的高患病率,且未發現相關因素,對此患者人群開展糖尿病視網膜病變早期評估,是及時發現和給予干預治療的重要手段。 關鍵字:糖尿病視網膜病變,危險因素,華人,高血壓,基層醫療 IntroductionDiabetes mellitus is a metabolic disease which is characterised by hyperglycaemia due to interactions between genetic and lifestyle factors. Type 2 diabetes is the most common type of diabetes among Hong Kong adults.1 According to the International Diabetes Federation, the prevalence of diabetes for adults in Hong Kong in 2013 was estimated to be 9.5%.2 People with diabetes are at an increased risk of developing various serious complications which can be broadly classified as cardiovascular and microvascular diseases, namely retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy.3 Diabetic retinopathy is one of leading preventable causes of visual impairment and blindness in working age population, aged 15 to 64 years old.4,5,6 The causes of visual loss in diabetic retinopathy include macular oedema, vitreous haemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment and neovascular glaucoma.6 As the early stage of diabetic retinopathy is asymptomatic, screening for this condition is important so that timely intervention can be provided to reduce the risk of developing visual impairment.7 Identified risk factors for diabetic retinopathy include age, male sex, obesity or overweight, longer duration of diabetes, elevated glycohaemoglobin levels, concurrent hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, pregnancy, presence of diabetic nephropathy, presence of cardiovascular disease and family history of diabetes.8-18 Incidentally, the use of fenofibrate was found to be protective for diabetic retinopathy.19 The reported prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus patients varied a lot in different countries.9-16, 20, 21 The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in European countries ranged from 5% to 39% 9, 15, 20, 21 while the prevalence in the Asia Pacific countries ranged from 6.2% to 25.5%. 11, 12, 13, 16 According to a local study in 2011, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy was 18.2% among newly diagnosed diabetes patients in Hong Kong.22 However, the study did not analyse the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in detail, regarding different demographic characteristics and might have included some patients with delayed diagnosis of diabetes. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), patients with type 2 diabetes should have an initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist or optometrist shortly after the diagnosis of diabetes.3 This recommendation was based on the evidence that some patients might have undiagnosed diabetes for a long time so that diabetic retinopathy might have already developed upon the diagnosis of diabetes. Structured diabetic complication screening programme was implemented in the Hospital Authority general out-patient clinics in Hong Kong since 2009. However, a long waiting time was anticipated due to a large and increasing burden of diabetes patients and limited resources. In view of the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and the importance of early screening for diabetic retinopathy, the possibility of prioritisation of high risk patients for diabetic retinopathy screening would allow timely detection and hence early management of these patients. More than 70 percent of the newly diagnosed diabetic patients identified in the general out-patient clinics were patients who already attended regular follow-up for hypertension. Around 25% of hypertensive patients had co-existing diabetes mellitus. Hypertension is a known risk factor for diabetic retinopathy.23 Therefore, in the general out-patient clinics, annual screening for diabetes would be performed for all hypertensive patients. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in patients with “new onset” diabetes is lacking. Many previous studies examined patients with newly diagnosed diabetes in which diabetes might have gone undiagnosed for many years. There was also limited research information on the associated factors for development of diabetic retinopathy in this group of patients. This study aims to answer the following research question: “what was the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care in Hong Kong”. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy while the secondary objective was to evaluate the associated factors of developing diabetic retinopathy in this group of patients. The results may guide us to prioritise patients at higher risk to have earlier diabetic retinopathy screening so that timely management could be provided. MethodStudy design This was a cross sectional study. The study was carried out in 3 general out-patient clinics located in one of the districts in Hong Kong. According to the Hospital Authority statistics, the three clinics served more than 12,000 type 2 diabetes patients and 28,000 hypertensive patients in the year 2013. All patients with new onset type 2 diabetes who fulfilled the inclusion criteria during the study period were included. The flow chart in Figure 1 illustrated the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. A list of patients from the participating clinics who had received diabetic complication screening from 1st January 2012 to 31st December 2013 were retrieved from the Diabetes Mellitus computerised data system of the Clinical Management System (CMS) of Hospital Authority in July 2014. Only patients with diabetes diagnosed in the year 2012 and who had their first diabetic complication screening performed within 1 year of diagnosis were included. New onset type 2 diabetes mellitus was defined as type 2 diabetes diagnosed according to World Health Organisation (WHO)24 or American Diabetes Association (ADA)3 diabetes diagnostic criteria within 1st January 2012 to 31st December 2012 and a screening test for diabetes was negative in the past 1 year. Case condition was defined as the presence of any degree of retinopathy detected via fundi photo examination whereas non-case condition is defined as no detectable retinopathy. The fundi photo examination was assessed by fundi photo machine Nidex AF-230 non-mydriatic auto fundus camera with a Canon EOS 5D SLR camera. Fundi photos were graded by trained optometrists using the software Digital Healthcare OptoMize version 2.A quality assured grading system was implemented for the diabetic retinopathy screening. A second grading by another optometrist was performed in 15% of normal and 100% of abnormal fundi photos. Fundi photos with a discrepancy in the grading results were arbitrated by an ophthalmologist of the University of Hong Kong for final decision. The severity of diabetic retinopathy was classified according to the United Kingdom National Guidelines on Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy, which classified diabetic retinopathy as no background pre-proliferative and proliferative diabetic retinopathy with or without maculopathy. Sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy was defined as pre-proliferative retinopathy or worse or the presence of sight-threatening maculopathy.25 This study was approved by Kowloon East Cluster / Kowloon Central Cluster Research Ethics Committee / Institutional Review Board.

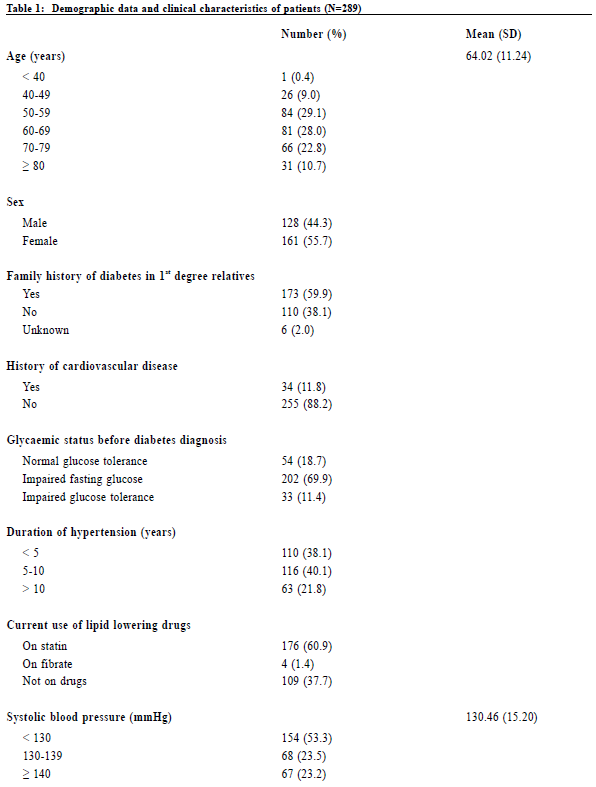

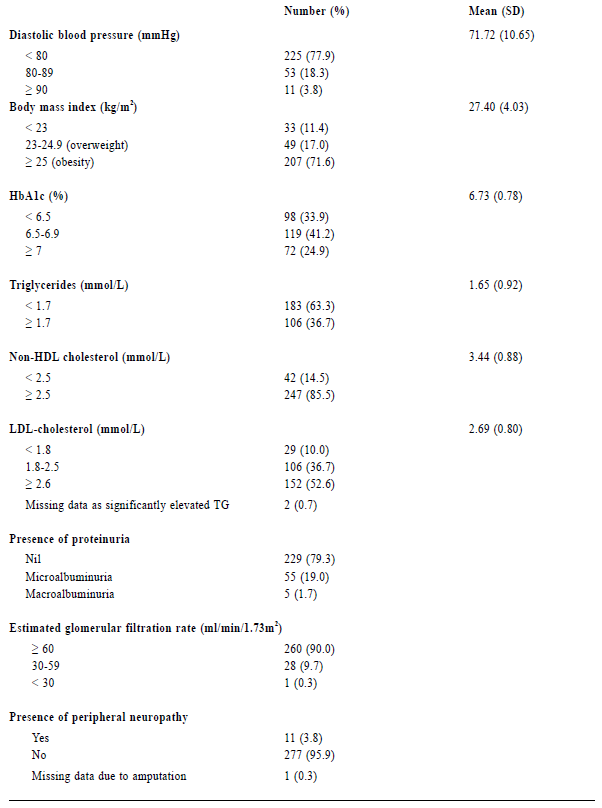

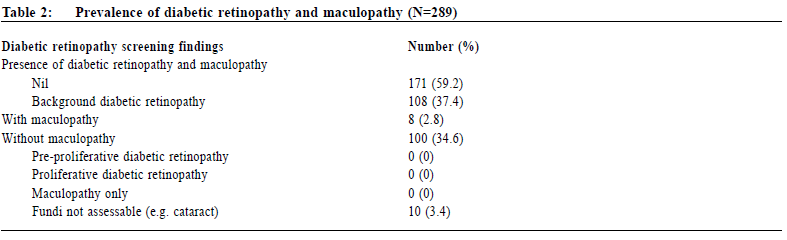

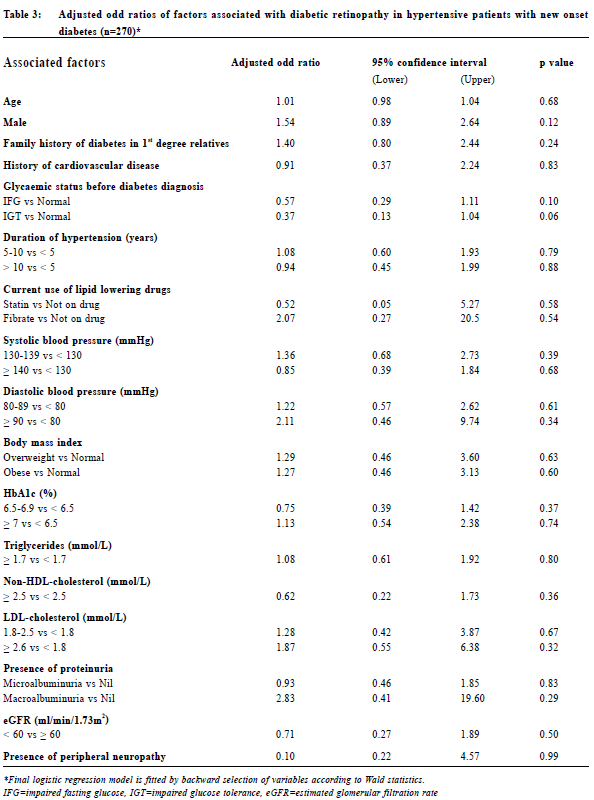

Data collection Data was collected by reviewing the medical records of CMS which included the medical consultation notes and diabetic complication screening reports. Collected variables included age, gender, family history of diabetes, history of cardiovascular diseases namely cerebrovascular disease, ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease, glycaemic status before diagnosis of diabetes (normal glucose tolerance, impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance), duration of hypertension and the current use of lipid lowering drugs (statin, fibrate or not on drug). The systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), glycated haemoglobin A1c level (HbA1c), lipid profile (triglyceride level, non-HDLcholesterol level and LDL-cholesterol level), presence of proteinuria (no proteinuria, microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and presence of peripheral neuropathy upon the diagnosis of diabetes would also be documented. The presence of diabetic retinopathy with its grading and/or maculopathy would be recorded. For the glycaemic status before diagnosis of diabetes, we defined normal glucose tolerance (NGT) as fasting glucose less than 6.1 mmol/L, impaired fasting glucose (IFG) as fasting glucose in the range of 6.1-6.9 mmol/L and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) as 2-h plasma glucose in the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) in the range of 7.8-11.0 mmol/L according to the WHO diagnostic criteria.24 Diabetic nephropathy is defined as the development of microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria.26 Presence of microalbuminuria was defined as 2 out of 3 urine samples showing albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) more than 2.5 mg/mmol for men and 3.5 mg/mmol for women while macroalbuminuria was defined as 2 out of 3 urine samples showing ACR more than 30 mg/mmol.27 Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation. According to the National Kidney Foundation classification, the staging of chronic kidney diseases are as follows: GFR ≥ 90 ml/ min/1.73m2 with other evidence of kidney damage (Stage 1), eGFR 60-89 ml/min/1.73m2 with other evidence of kidney damage (Stage 2), eGFR 30-59 ml/min/1.73m2 (Stage 3), eGFR 15-29 ml/min/1.73m2 (Stage 4) and eGFR < 15ml/min/1.73m2 (Stage 5).28 The presence of diabetic neuropathy is defined as abnormal vibration threshold (more than 25V) detected by a biothesiometer on the big toe or abnormal light touch perception detected by a 10-g monofilament at the 4 plantar sites on the forefoot, including great toe and heads of first, third, and fifth metatarsals.29 All data were documented in a data collection spreadsheet for further data analysis. Sample size calculation There was no reported prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in hypertensive patients with new onset diabetes both locally and internationally. A local study showed that the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy was 18.2% in patients with newly diagnosed diabetes.22 Therefore the quoted prevalence of 18.2% was chosen for the calculation of sample size. Assuming that we have a population proportion of 0.18, the minimum sample size to obtain 5% absolute precision with 95% level of significance would be 227.30 Since the number of eligible subjects of this study was just slightly larger than the calculated sample size, all eligible subjects of the participating clinics would be recruited. OutcomesThe primary outcome was to evaluate the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus. Secondary outcome was to evaluate the associated factors of diabetic retinopathy. Statistical analysis All data were analysed using statistical program SPSS version 21.0. Proportions were presented by percentages. Continuous data with normal distribution were presented by mean with standard deviations. Univariate analysis of categorical variables was The Hong Kong Practitioner VOLUME 39 September 2017 73 Original Article performed by Chi-square test and Fisher ’s exact test. Univariate analysis of continuous variables was performed by independent sample t-test or Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Multivariate analysis was performed by means of logistic regression. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. ResultsStudy population 289 Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus were included in our study (Figure 1). Clinical characteristics of the subjects were summarised in Table 1. The mean age was 64 years in which 55.7% were female. More than half of the patients (59.9%) had a family history of diabetic mellitus in their 1st degree relatives. 81.3% of patients were found to have abnormal glucose tolerance (either IFG or IGT) before diabetes was diagnosed. 88.6% of the subjects were either obese or overweight. The prevalence of diabetic nephropathy and peripheral neuropathy were 20.7% and 3.8% respectively. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy was illustrated in Table 2. In our study, 37.4% of patients were found to have background diabetic retinopathy in which 2.8% had maculopathy (i.e. sight-threatening). No patients were found to have preproliferative or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Associated factors for diabetic retinopathyLogistic regression was used to determine significant risk or protective factors associated with diabetic retinopathy in hypertensive patients with new onset diabetes (Table 3). 270 patients were included for data analysis with 19 missing data as shown in Table 1 and 2 (6 patients with unknown family history of diabetes in 1st degree relatives, 2 patients with LDL-cholesterol not shown, 1 patient with peripheral neuropathy not assessable due to amputation and 10 patients with non-assessable fundi). No statistically significant association was observed between diabetic retinopathy and all the factors mentioned above.

DiscussionIn our study, more than one-third (37.4%) of Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus were found to have diabetic retinopathy upon diagnosis. This was higher than that reported in a previous local study (18.2%).22 Moreover, the prevalence was also higher than that reported in European and other Asia Pacific countries.9-16 This might be because our subjects were hypertensive patients instead of the general population. Hypertension was a known risk factor for the development of diabetic retinopathy. Moreover, in one recent study in Korea11 diabetic retinopathy screening was assessed by ophthalmologist with indirect fundoscopy. This might underestimate the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy when compared with the use of fundus photos as in our study.31 A study conducted in Singapore found that diabetic retinal photograph achieved a higher sensitivity in capturing diabetic retinopathy compared to a clinical examination by the ophthalmologist.32 The high prevalence found in our study proved that diabetic retinopathy was a common complication in our hypertensive patients with new onset diabetes mellitus. Although none of these patients were found to have pre-proliferative or proliferative diabetic retinopathy, early diabetic retinopathy screening is still warranted for every hypertensive patient with new onset diabetes to allow timely detection and intervention.

The results did not identify any risk or protective factors to have statistically significant association with diabetic retinopathy. One of the reasons might be our subjects had new onset diabetes, as compared to other studies which might include patients with a delayed diagnosis. Previous studies showed that high blood pressure and poorly controlled diabetes were risk factors for diabetic retinopathy.10, 11, 13, 14, 15 However, among our subjects, most of the patients had their blood pressure and HbA1c adequately controlled upon the diagnosis of diabetes. 53.3% of patients achieved the systolic blood pressure less than 130mmHg, 77.9% of patients achieved the diastolic blood pressure less than 80mmHg while 75.1% of patients achieved the HbA1c less than 7 mmol/l. As a result, the effect of high blood pressure and HbA1c levels might be masked. Concerning the protective factors for diabetic retinopathy such as the use of a fibrate, the effect might be underestimated due to the small number of diabetic patients being put on this drug. From our study, a high prevalence of diabetic retinopathy was found in our Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset diabetes. No statistically significant associated risk or protective factors were identified. We would therefore recommend all Chinese hypertensive patients with a new onset of type 2 diabetes to have early diabetic retinopathy screening. LimitationsWe acknowledge some limitations in our study. Firstly, the subjects in this study were recruited from three general outpatient clinics in a local district which limits the generalisability of our results to the whole local population of Hong Kong. Secondly, the population of diabetes patients with some associated factors was small and the significance of these associated factors for diabetic retinopathy might be underestimated. Thirdly, due to the long waiting time for diabetic complication screening in the participating clinics, patients with diabetic retinopathy screening within 1 year of diagnosis were included for analysis. The actual onset time for diabetic retinopathy within this group of patients with new onset diabetes might not be fully ascertained. ConclusionThe prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in our studied Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus was higher than that reported in other countries who studied the general diabetes population. No statistically significant association was observed between known risk or protective factors and diabetic retinopathy in our Chinese hypertensive patients. This emphasises that early screening for diabetic retinopathy for all Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset diabetes patients is important. Further research should focus on the cost effectiveness of early screening for diabetic retinopathy for all Chinese hypertensive patients with new onset diabetes. Michelle SS Fu, FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKCFP) Correspondence to: Dr Michelle SS Fu, 99 Po Lam Road North, Tseung Kwan O,Hong Kong SAR.E-mail: siusaapmichellefu@yahoo.com.hk

References

|

|