|

September 2017, Volume 39, No. 3

|

Update Article

|

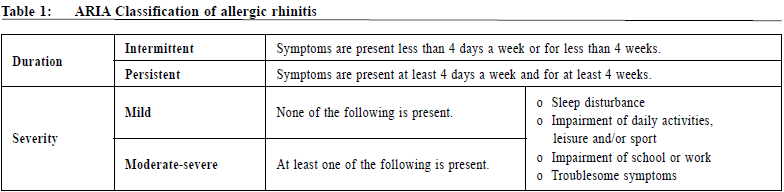

Management of allergic rhinitis for the family physiciansWai-man Yeung 楊偉民 HK Pract 2017;39:88-94 Summary Allergic rhinitis is a common problem in family medicine. This review article aims to provide updated practical information, including clinical presentations, diagnosis, classification and treatment of allergic rhinitis, for the family physicians. 摘要 過敏性鼻炎是家庭醫學中常見的疾病。本文旨在為家庭醫生 提供最新的實用信息,包括過敏性鼻炎的臨床表現、診斷, 分類和治療。 IntroductionAllergic rhinitis is a common problem in the practice of family medicine. It represents a global health problem affecting 10 to 20% of the population. This is probably an underestimate, because many patients do not recognise rhinitis as a disease. The prevalence is increasing.1 Although allergic rhinitis is often perceived as trivial, it is a major chronic respiratory disease, and affects patients’ social life, school performance, and work productivity. The patient may have tried some over-the-counter medications before coming to you. Apart from asking for more effective treatment, the patient may want to know whether the condition is curable, why some people suffer from this disease while others do not, anything the patient can do to prevent it, etc. This review article aims to provide practical information on the management of allergic rhinitis for family physicians. DiagnosisWhat is allergic rhinitis? Rhinitis may be allergic or non-allergic.2 Allergic rhinitis is defined as a condition with symptoms of sneezing, nasal pruritus, airflow obstruction, and mostly clear nasal discharge caused by IgE-mediated reactions against inhaled allergens and involving mucosal inflammation driven by type 2 helper T (Th2) cells.3 Allergens of importance include seasonal pollens and molds, as well as perennial indoor allergens, such as dust mites, pets, pests, and some molds. The pattern of dominant allergens depends on the geographic region and the degree of urbanisation.4 Specifically, occupational allergic rhinitis is defined as rhinitis directly attributable to a specific substance encountered in the work environment. Such occupational exposures include animal allergens (research laboratory workers, veterinarians), grain and flour dust (bakers, flour mill workers) and plant allergens (gardeners, farmers).5 Allergic rhinitis was previously classified as perennial and seasonal. A new classification of allergic rhinitis is in terms of duration and severity of symptoms known as the “Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma” (ARIA) classification and is shown in Table 1.1 Non-allergic rhinitis can be due to viral and bacterial infections, hormonal imbalance, exposure to physical agents, and side-effect of some drugs.1 These drugs may include various antihypertensives, aspirin, phenothiazines, oral contraceptives, cocaine and marijuana. However, allergic rhinitis can coexist with non-allergic forms (mixed rhinitis). What are the clinical presentations of allergic rhinitis? Allergic rhinitis can present as rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction or blockage, nasal itching, sneezing, and postnasal drip that resolve spontaneously or with treatment. Because similar respiratory symptoms occur frequently in young children with viral infection, it is very difficult to diagnose allergic rhinitis in the first 2 or 3 years of life. The prevalence of allergic rhinitis The Hong Kong Practitioner VOLUME 39 September 2017 89 Update Article peaks in the second to fourth decades of life and then gradually diminishes.6, 7 Allergic rhinitis and asthma are also linked by epidemiological, pathological, physiological characteristics and by a common therapeutic approach. Asthma has been found in as many as 15% to 38% of patients with allergic rhinitis, and some studies estimate that nasal symptoms are present in at least 75% of patients with asthma.1 Atopic eczema frequently precedes allergic rhinitis.8 Patients with allergic rhinitis usually have allergic conjunctivitis as well.9 The factors determining which atopic disease will develop in an individual person and the reasons why some people have only rhinitis and others have rhinitis after eczema or with asthma remain unclear. Allergic rhinitis is also associated with periodontitis10 and eosinophilic oesophagitis.11 Allergic rhinitis can be complicated with infectious rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, otitis media, and nasal polyps1, and also sleep problems.4 What are the risk and protective factors of allergic rhinitis? Having a parent with allergic rhinitis more than doubles the risk.12 Having multiple older siblings and growing up in a farming environment are associated with a reduced risk of allergic rhinitis. It is hypothesised that these apparently protective factors may reflect microbial exposures early in life that shift the immune system away from Th2 polarisation and allergy.13, 14 ManagementHow to diagnose allergic rhinitis? The diagnosis of allergic rhinitis is often made clinically on the basis of characteristic symptoms and a good response to empirical treatment with an antihistamine or nasal glucocorticoid. The assessment includes a detailed history of duration of symptoms, any sleep disturbance, impairment of daily activities (leisure, sport, school or work) or any troublesome symptoms, and presence of other atopic diseases, as well as potential triggers. Family history of atopic diseases should also be looked for. The physical examination includes nose, throat, eyes, ears, chest and skin. Formal diagnosis is based on evidence of sensitisation, measured either by the presence of allergen-specific IgE in the serum or by positive epicutaneous skin tests (i.e., wheal and flare responses to allergen extracts) and a history of symptoms that correspond with exposure to the sensitising allergen.4 But these tests are seldom done in primary care practice.

How to treat allergic rhinitis? Among different therapeutic measures, allergen avoidance, antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids are considered the cornerstone of first-line therapy, which should be initiated by a general practitioner15 or family physician. Other kinds of treatment are discussed below, and family physicians should tailor-make the treatment plan according to the individual needs of different patients. The different kinds of therapeutic agents and their common or severe adverse effects are illustrated in Table 2. A treatment plan for different classes of allergic rhinitis is illustrated in Table 3. Allergen avoidance Allergen avoidance should always be considered, though could be difficult. Avoidance of seasonal inhalant allergens is universally recommended on the basis of empirical evidence, but the efficacy to avoid exposure to perennial allergens, including dust mites, pest allergens (cockroach and mouse), and molds, has been questioned. For abatement strategies to be successful, allergens need to be reduced to very low levels, which are difficult to achieve. Abatement usually requires a multifaceted and continuous approach, raising feasibility problems.4 Nonetheless, house dust mites is a common allergen source in humid areas, and a combination of stringent environmental control measurements (Table 4) can be recommended to patients or parents of young children. Besides, the diagnosis of occupational allergic rhinitis should be considered a sentinel workplace health event and alert the employer that further control is required.5 PharmacotherapyAntihistamines Drug therapy usually starts with oral antihistamines. Later-generation antihistamines are less sedating than older agents and are just as effective, so they are preferred.17,18 Because of their relatively rapid onset of action, antihistamines can be used on an as-needed basis. The few head-to-head trials of nonsedating antihistamines have not shown superiority over another.19 H1-antihistamines are also available as nasal sprays. The intranasal preparations appear to be similar to oral preparations in efficacy but may be less acceptable to patients owing to a bitter taste.20 Some first-generation antihistamines have shown teratogenic effects in animals, but not in humans. Withdrawal symptoms (tremor, irritability) have been reported in babies whose mothers received large doses of first-generation antihistamines prior to delivery, and in babies who are being breast-fed, since antihistamines are excreted in breast milk. There is no evidence of teratogenic effects with second- and third-generation antihistamines. However, their use in pregnancy is only recommended if the benefits to the mother significantly outweigh any potential risks to the foetus. Both loratadine and cetirizine are known to be excreted in breast milk; it is not known whether this is also the case for fexofenadine, so its use in nursing mothers should be done with caution. Loratadine and cetirizine are classified as pregnancy category B, whereas fexofenadine is classified as category C. Category B is defined as animal studies not showing any foetal risk and no human studies done or animal studies showing foetal risk, but human studies showing no risk. Category C is defined as foetal risk in animal studies without adequate human studies or no adequate animal or human studies.21

Nasal decongestants The effect of antihistamines on nasal congestion is modest.22 They can be combined with oral decongestants to improve nasal airflow in the short term (on the basis of data from trials lasting 2 to 6 weeks), at the cost of some side effects.23, 24 Topical nasal decongestants are more effective than oral agents, but there are reports of rebound congestion (rhinitis medicamentosa) or reduced effectiveness beginning as early as 3 days after treatment25, and only short-term use is recommended. Leukotriene-receptor antagonists The effect of leukotriene-receptor antagonists on the symptoms of allergic rhinitis is similar to or slightly less than that of oral antihistamines, and some randomised trials have shown a benefit of adding the leukotriene-receptor antagonist montelukast to an antihistamine.4 Intranasal glucocorticoids Intranasal glucocorticoids reduce nasal inflammation. They are useful in children with moderate-to-severe or persistent symptoms and start to be effective after 1–2 weeks and need to be taken on a daily basis for at least 6 weeks. Intranasal glucocorticoids are not suitable for acute symptom relief. Topical side effects of intranasal glucocorticoids are minimal, and concerns of systemic side effects such as suppression of growth and bone metabolism have been allayed.26, 27 Intranasal glucocorticoids are more efficacious than oral antihistamines or montelukast, but the difference may not be as evident if the symptoms are mild.4 There are insufficient data to determine whether the effectiveness differs among various intranasal glucocorticoids. An oral H1-antihistamine plus montelukast is an alternative for patients for whom nasal glucocorticoids are associated with unacceptable side effects or for those who do not wish to use them; the efficacy of this combination is not unequivocally inferior to that of an intranasal glucocorticoid.4 For the ocular symptoms of allergy, intranasal glucocorticoids appear to be at least as effective as oral antihistamines.9

Allergen Immunotherapy Subcutaneous immunotherapy and sublingual immunotherapy In general population or general practice surveys, a third of children and almost two thirds of adults report partial or poor response with pharmacotherapy for allergic rhinitis.28, 29 The next step in treating such patients is allergen immunotherapy. Immunotherapy has been proven to be effective against grass, pollen and house dust mites allergy. It had been suggested that immunotherapy should be started early, even in children with well controlled symptoms30 because it has a preventive effect on the progression from rhinitis to asthma.31 The family physician should discuss immunotherapy early in the disease process. If a family considers immunotherapy as a treatment option, the child needs to be referred to an allergist. Asthma can become worse while the child is on immunotherapy and therefore it needs to be adequately controlled before commencement of immunotherapy.

Both subcutaneous immunotherapy and sublingual immunotherapy using rapidly dissolving tablets are available and have a good safety profile. Fatal and nearfatal reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy are very rare in children.32 Subcutaneous immunotherapy needs to be given in a surgery with adequate resuscitation facilities by trained clinicians. A full course of immunotherapy takes 3–5 years. The allergen extract is given in increasing concentrations, initially weekly, then on a monthly basis to induce tolerance. Sublingual immunotherapy is safe for home administration and needs to be taken on a daily basis.33 In sublingual immunotherapy, a fixed dose of allergen is delivered beginning 12 to 16 weeks before the anticipated start of the allergy season. First effects of subcutaneous immunotherapy and sublingual immunotherapy are expected after a few months of treatment. With immunotherapy, unlike pharmacotherapy, the effect persists after the discontinuation of therapy. The clinical effects may be sustained for years.34 Immunotherapy down-regulates the allergic response in an allergen-specific manner by mechanisms under elucidation. In addition to having proven efficacy in controlling allergic rhinitis, immunotherapy also helps control allergic asthma and conjunctivitis.35 Other modes of treatment Recombinant anti-IgE antibody Apart from all the above therapies, recombinant anti-IgE antibody (omalizumab) has been applied with success in the treatment of allergic rhinitis, particularly in combination with subcutaneous immunotherapy, but is very expensive and not widely used in routine practice. Toll-like receptor agonists have also been proven to be beneficial.36, 37 Nasal douching Saline nasal douching or irrigation using isotonic solution helps to wash out sticky mucus from the nose. It can be recommended as complementary therapy in reducing symptoms in children and adults with allergic rhinitis. It is safe, well tolerated, inexpensive, easy to use, and there is no evidence showing that regular, daily saline nasal irrigation adversely affects the patient's health or causes unexpected side effects.38, 39 Surgical treatment Clinicians may offer, or refer to a surgeon who can offer, inferior turbinate reduction in patients with allergic rhinitis with nasal airway obstruction and enlarged inferior turbinates who have failed medical management.40 ConclusionThe knowledge about allergic rhinitis is extensive. This review article can by no means be exhaustive but aims to provide some practical information for the family physicians to take care of their patients. The diagnosis of allergic rhinitis is usually based on clinical information which includes physical symptoms and the psychosocial impairment as a result of the disturbing symptoms. Allergen avoidance, antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids are considered the cornerstone of first-line therapy. Other modes of therapy should be borne in mind and referral to an allergist for immunotherapy should be considered if other treatments failed. The care of patients with allergic rhinitis is an example of how a family physician can take up the role as a patient-centred, continuing, comprehensive and coordinated care-provider.

Wai-man Yeung,FRCSEd, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Correspondence to:Dr Wai-man Yeung, Medical & Health Officer Specialist,

Peng Chau General Out Patient Clinic, 1A, Shing Ka Road, Peng

Chau, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|