|

September 2017, Volume 39, No. 3

|

Update Article

|

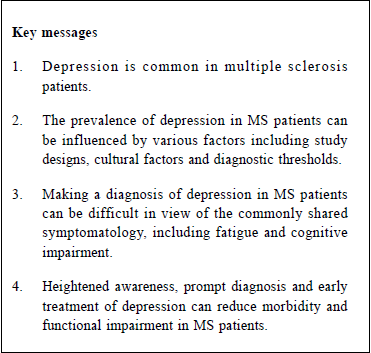

Prevalence of depression in multiple sclerosis: a systematic reviewEvelyn KY Wong 黃潔儀 HK Pract 2017;39:95-104 Summary Depression is common in pat ients wi th mul t iple sclerosis (MS); however, its prevalence varies among different studies. A systematic review was conducted according to the Pr efer r ed Repor t ing I tems for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. Eleven studies were included in this systematic review analysis. Depression was consistently more prevalent in MS patients than in the general population, ranging from 4.4 - 45.8%. Women with MS were found to have a higher risk of depression than men with MS. However the risk when compared with the general population was more marked in men with MS. Study design, cultural as well as societal factors might contribute to this heterogeneity among the studies. Further studies are needed to better assess the temporality between depression and the clinical phases of MS. Meta-analysis can be helpful in identifying risk factors for depression in MS patients. A multi-factorial formulation may help with clinical management, while clinical attention and awareness are crucial for the prompt treatment of depression in MS patients. This might in turn minimise the morbidity and mortality in this patient group. 摘要 抑鬱症在多發性硬化症病人中相當常見,但不同研究顯示不 同的病發率。本文根據 PRISMA 模式,為11篇相關研究報告 進行系統性分析。結果一致顯示多發性硬化症病人患抑鬱症 的比率較平常人高,比率由4.4%至45.8%不等。在多發性硬化 症病人中,女性較男性患抑鬱症的比率為高。但當比較多發 性硬化症病人和一般人仕時,男性患者則較易出現抑鬱症。研究設計、文化和社會因素都可能導致各研究間結果的差 異。未來研究需要更好地評定抑鬱症和多發性硬化症在病程 階段時間上的關係。統合分析可以幫助確定抑鬱症在多發性 硬化症中的病發風險因素。多因子解析有助臨床治療。但臨 床上的關注和警覺至為重要,及時為抑鬱症進行適當治療將 減低患者承受的障礙和影響,也可降低他們的死亡機會。 IntroductionMultiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic debilitating neurological condition which presents with various neuropsychiatric symptoms, including affective symptoms. Depression is found to be more prevalent in patients with chronic medical illness.1,2 This might be explained by various multiple factors.3 Though known to be common,the prevalence rate of depression in MS varies largely between studies.4 In Hong Kong, the twelve–month prevalence of DSMIV major depressive episode measured by a largescaled community study was 8.4%.5 Local data on the rate of depression in MS using standardised structured psychiatric interview is lacking. A recent study using the General Health Questionnaire-28 showed higher rates of depressive symptoms among the patients with MS in Hong Kong.6 Using the Beck Depression Inventory-II, Lau et al., showed a mean score of 14.9 among the local MS population, which indicates mild depression.7 Numerous studies have extensively looked at the epidemiology of depression in this population and investigated for possible factors contributing to its clinical manifestation.8 Despite the abundance of evidence, important questions still remain unanswered. Inconsistencies and even contradictory findings across studies raise concerns over methodological issues, while analysing these controversies may shed light on the underlying pathogenesis of both multiple sclerosis and depression.

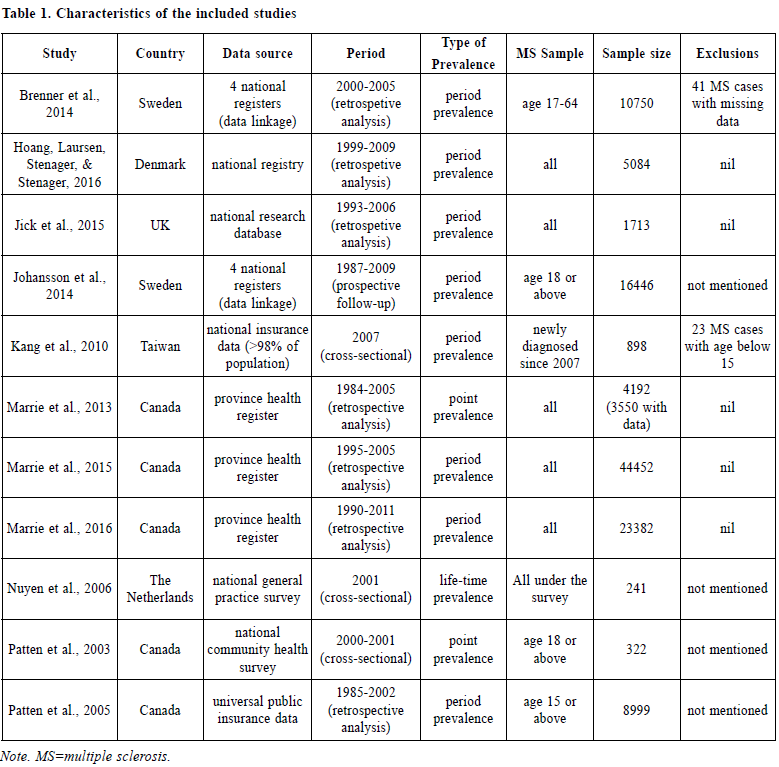

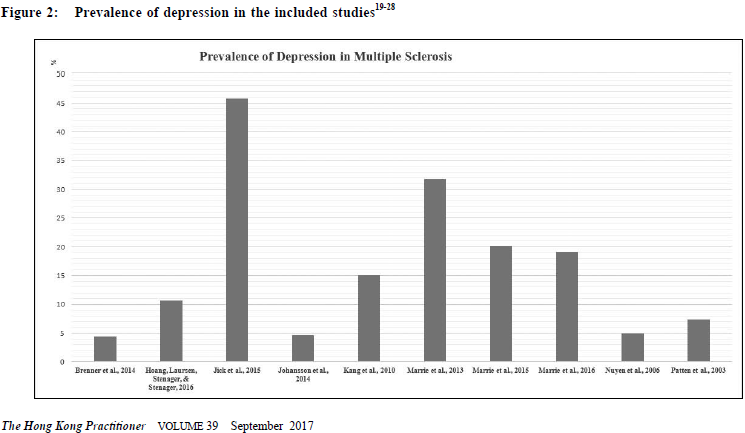

Depression carries a huge economic burden9 while MS, as a chronic medical illness, also utilises a vast amount of public health resources.10 A better knowledge of its prevalence and risk factors are valuable for clinical management and healthcare sourcing. For this reason, this systematic review looks at the prevalence rate of depression in MS patients through a critical appraisal of the methodologies of available literature, followed by a discussion on its clinical implications. MethodA systematic review was conducted based on the PRISMA statement in 2009.11 Data collection An initial search was conducted in MEDLINE (including non-indexed and in process) and EMBASE, from 1946 onwards to January, 2017. The search keywords were: MS and “depress*” or "emotional" or "mood". The abstracts were screened for the inclusion criteria. Full-texts were obtained from electronic databases, the Barnes library of the University of Birmingham and Google Scholar.12 Online databases including OpenGrey13, ClinicalTrials.gov14 were searched for unpublished studies. Additional articles were looked for by screening through the reference lists of the records from the initial search. All the studies, including the conference abstracts, were then screened for those that fit the exclusion criteria. Emails were sent to some authors for their study details and raw data when indicated, or fulltexts not otherwise located. Eligibility criteria Inclusions criteria were: 1) published in English, 2) conducted on humans, 3) primary clinical study, 4) involved patients with multiple sclerosis, 5) with at least one quantitative measure of depression or depressive symptoms. Exclusion criteria were: 1) diagnosis of depression not based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)15 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)16; diagnostic schedules based on ICD or DSM were accepted, 2) unclear or biased sampling processes. Diagnosis of depression A diagnosis of depression had to be established by ICD or DSM. Several diagnoses involving low mood were not included (Appendix I). Methodology quality assessment A critical appraisal tool for epidemiology studies17 was selected among the 86 tools assessed by Sanderson and colleagues.18 A scoring system comprising of eight specific items, with one point given for good performance in each (Appendix II) was selected. A guideline for this scoring system was provided with the original paper. RESULTSEleven clinical studies were included in this systematic review.19-29 (Table 1 and Figure 1) Major results Patten et al., 200529, grouped depression under “affective disorders”, without differentiating between unipolar and bipolar types. Isolated prevalence of depression was therefore not available. In the remaining ten studies, the prevalence of depression in MS ranged from 4.4% to 45.8% (Figure 2).

Patten et al, 200328 proved the persistence of a higher depression rate after adjusting for age and gender. Similar to the general population, depression is more prevalent in women than men with MS as shown in several of the included studies. However, the association between affective disorders in MS patients was stronger in men despite an overall higher prevalence in women according to Patten et al, 200529 and Marrie et al., 2015.25

In addition, Johansson et al., 201422 found a higher risk of depression in MS patients while the risk of MS was also found to be higher with depression counted as an exposure. Interestingly, a subsequent study by Hoang, Laursen, Stenager & Stenager in 201620 found no significant difference comparing the prevalence of depression before and after the diagnosis of MS, both of which were higher than that of the general population. In other words, the population who was diagnosed with MS later had a higher risk of depression even before the clinical manifestations of MS. It is worthwhile noting that different measurements were adopted when reporting prevalence between the various studies. Most of them measured period prevalence, while point prevalence and life prevalence were measured in some of the studies (Table 1). Methodology quality assessment Methodological assessment for individual studies was summarised in Table 2. A few points were highlighted here. A) Sampling The data collected by Patten et al., 200328 was from a large population survey which adopted a complex way of sampling, involving both clustering and stratification with the application of sampling weights. The choice between proportionate or disproportionate stratified sampling was not reported in this paper, yet this was important as the latter and the commonlyaccompanied weighting in statistical analysis could lead to a reduced precision of the estimates.30 Other sources of information31 showed that the data were collected by area frames and phone frames respectively, from randomised clustered sample after proportionate stratification. The different sampling frames could lead to unequal probabilities of individual subjects being selected and hence sampling errors. B) Measurement of depression All the included studies shared the common strength of using a standardised diagnostic criteria for the establishment of depression, which maximises diagnostic consistency among researchers and identifies clinically significant cases. The use of self-rated questionnaires in most other studies would lead to an over-estimation of depression.32 However it was arguable that all MS patients with depression was completely accounted for in the included studies as there is bound to be cases which have never come to clinical attention (and hence were missing from the medical records). These might otherwise be picked up by self-reported questionnaires.

C) Measurement of prevalence In studying prevalence, eight out of eleven of the included studies looked at period prevalence. Life-time prevalence, which reflects accumulative incidence, should theoretically be the highest while it would be lowest for point prevalence if measured in the same sample. Life-time prevalence was an unusual form of period prevalence, in which the period is not fixed but varies according to the individual subjects’ age.33 For example, the life-time prevalence of a sample comprising of subjects of 40 years old is a measurement of its 40 years’ period prevalence, while the life-time prevalence of another sample comprising of subjects of 50 years old is a measurement of its 50 years’ period prevalence. The capture of prevalence in the two types of measurement is different by nature. To illustrate further, we could take the studies by Johanssan et al. and Nuyen et al. as examples. In Johanssan et al., 2014, the period prevalence of the sample from 1987-2009 was measured. It means all subjects with depression diagnosed during the period of the 22 years were counted in the calculation of the prevalence rate. In contrast, in Nuyen et al., 2006, the life-time prevalence of the sample was measured cross-sectionally in 2001, which means that by the time of the survey in 2001, all survey participants who had ever been diagnosed depression at any point in their life would be counted in the calculation of the prevalence rate.

To further elaborate on this point, if a subject had depression diagnosed in 1980 but achieved full remission before 1987, even if the subject participated in the study by Johanssan et al., the subject would be counted as negative in the prevalence rate calculation; however, the same subject would be counted as positive in the study by Nuyen et al. because it was measuring the life-time prevalence as it counted all subjects who had ever had a history of depression; regardless of their remission status at the time of the study. It was because, that depression as a disease entity should not be regarded as an irreversible illness, in which the latter was to be treated as a permanent entry (an example would be Alzheimer’s disease). In this review, apart from the aforementioned heterogeneity among the use of life-time prevalence and period-prevalence, even the survey time frames also vary largely amongst the studies measuring period prevalence. For example, any episodes of depression within 22 years were counted in Johansson et al., 201422, while Kang et al., 201023 only counted the depression in the past one year. It implied that the studies were looking into depression prevalence from quite different perspectives. D) Comorbidities as confounders While multiple medical illnesses is a risk factor for depression1,2, co-morbidities were not documented in most studies. Assumption of its absence is nonjustifiable, particularly in the elderly group. This certainly serves as a major confounder in the prevalence rates. E) Statistical analysis As mentioned earlier, in Patten et al., 200328, a special statistical analysis method was adapted to counteract the potential bias brought by their complex sampling methods. Despite the adaptation of proportionate sampling, weighting was still used in the calculation of the prevalence of depression, probably for the adjustment of non-response in the survey.34 Yet, the use of weighting would increase the variance of estimates30, which was reflected by the generally poor precision of the prevalence rates in this study. The wide confidence intervals weakened the results’ validity due to the higher chance of the observed mean being a result of sampling error. DiscussionsDifferences in prevalence rates amongst the various studies The prevalence rates of depression varied widely in literature, and this was also reflected in this review though to a lesser extent. The high prevalence found in Marrie et al., 201324 could neither be explained by the survey period length (depression was only counted in the past one to five years) nor cultural factors, as the high prevalence rate was not observed in another study28 from the same country. The difference could be genuine or due to the effects of the study design. It was conducted 10 years later than Patten et al., 200328, and the rise could be related to the decreased social stigma once associated with depression and hence a rise in the number of cases coming to clinical attention. However the extent of this increase is unlikely to be solely responsible for this phenomenon. Looking at design effects, the lower rate in Patten et al, 200328 might be related to the design of their community survey, which carried a recall bias. This bias was minimised by Marrie et al, 201324 as their study involved collecting data from the medical records in a public healthcare system. The reported p revalence rate could also be affected by other non-statistical factors. Since most of the included studies collected data retrospectively via medical records in registries, the prevalence rates largely depended on whether the subjects had undergone any psychiatric assessment, which was in turn related to various factors such as cultural reasons, the extent of stigma in the societal context, the awareness of mental illness in that particular population, as well as the availability of local psychiatric services. In other words, the absence of any history of depression did not imply the actual absence of illness in the subjects. The awareness of medical practitioners also play a role in the diagnostic rates of depression for that population. The diagnosis of MS would probably alert the medical practitioners to screen for mental comorbidities, with depression being at the top of the list. This may result in a lower rate of under-diagnosis of depression in the MS population compare to the general population. On the other hand, the exceedingly high prevalence of depression found in Jick et al., 201521 raised a concern over the difference in the diagnostic culture among different countries. Making the diagnosis is the most debated subject in psychiatry. One of the major pitfalls in making a diagnosis by the standardised diagnostic criteria is the lack of consideration of cultural factors in the clinical formulation of the manifestation of any mental phenomena. A major revision in DSM-5 is the change in the diagnostic paradigm from categorical to dimensional approach and the introduction of cultural formulation interview.35 Various factors can influence the diagnosis of depression, including differences in explanatory models, willingness of patients to disclose all their symptoms, somatic presentations, and variations of the presentation in clinical features across cultures.36-38 Diagnostic threshold, which differs across cultures, also influence the rate of diagnosed depression in different countries.39 As it is the only one among the included studies conducted in United Kingdom, whether the difference in making a clinical diagnosis of depression affected the epidemiological results would be of interest in future studies. Some potential factors which could be related to the differences seen in the measurement of prevalence were under-investigated. One of these is the subtype of MS. Among the included studies, only one of them described the subtypes of MS in the sample.21> It is well-known that patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) carries a worse prognosis than relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). The former suffered from more physical disability and hence have more psychosocial sequelae.>40 Memory impairment is also found to be more prominent with PPMS and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) than with RRMS.41 It is reasonable to suspect that patients with PPMS and SPMS carry a higher risk of developing depression over their course of illness. Apart from the subtypes, the symptomatology in different subjects may also predict the development of depression.40 Diagnostic challenge of depression in MS Some symptoms, like fatigue and cognitive problems, were commonly shared by MS and depression. It was difficult to delineate their attribution.42,43 Being a diagnosis based primarily on symptomatology instead of the underlying aetiology, depression could be overestimated in these circumstances. This is a major pitfall of self-reported questionnaires, yet this limitation could not be fully eliminated even with structured clinical assessments performed by experienced psychiatrists. As mentioned earlier, there are drawbacks with either methods, but one has to strike a balance between sensitivity and specificity. In general there is a favour for a higher sensitivity for screening tests44, trading off for more false positives. The decision to use which is based on the objectives of individual studies. Delineation of the temporality between depressive semiologies and clinical phases of MS might be useful in diagnosing genuine depression and searching for its etiologies. They could be part of the physical sequelae of MS4, common biological factors in the genesis of both conditions8, side effects of treatment45, or psychological reactions to chronic illness.4,8 Each of these carry different but equally significant clinical implications, which warrant further investigations. Treatment for depression in MS Timely treatment of depression in MS patients is important for the quality of life and prognosis of the patient. However, well-designed studies on this were sparse. To date, there were isolated studies on the use of selective serotonin receptor reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), including sertraline, paroxetine and duloxetine, or despiramine, which is a tricyclic antidepressants, or moclobemide, which is a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A. The use of SSRI served an advantage over other pharmacological choices in reducing somnolence, cognitive impairment or exacerbation of fatigue. Psychotherapy is an alternative in treating depression in MS patients with cognitive behavioral therapy having a good clinical effect over short-term.46 Limitations of this reviewLimited by the nature of a systematic review, this study failed to statistically identify an accurate prevalence rate of depression in MS patients and its associated risk factors. A meta-analysis could help, but this was inappropriate here for two reasons. Firstly, due to missing data, only nine studies were eligible for meta-analysis, which could lead to invalidity of the results from meta-regression, and hence moderators for depression could not be found. Secondly, the studies were measuring different types of prevalence, while a pooling of life-time prevalence with point-prevalence was not considered to be statistically meaningful. To solve these, future systematic reviews can focus on a certain kind of prevalence measure, with the use of meta-analysis to look for heterogeneity and moderators on prevalence rates. However, in order to allow a sufficient number of them to be recruited into meta-regression, a compromise in the methodological qualities of included studies would be needed. Directions on future researchThere has been a vast amount of studies on depression in MS patients, yet some important questions remain unanswered. One of these is the formulation of depression in this particular population. Arnett, Barwick & Beeney4 suggested a theoretical model, which comprised of MS disease factors, common MS sequelae and possible moderators including coping, social support, stress and conceptions on self and illness, which might serve as a good reference in clinical practice while formulating the management plan of patients with MS and comorbid depression. For future research, potential predictors including age, gender, educational level, illness duration, age of illness onset and number of relapses of MS, should be measured and their correlation with depression should be investigated. Correlating depression with the subtypes and the clinical phases of MS may provide clues to the underlying pathogenesis. Nonetheless, depression warrants cautious clinical attention. Depression in itself carries morbidity and mortality, and causes significant impairment in social and occupational functioning.47-49 Untreated depression could also hinder the physical recovery of MS by either poor treatment adherence or hastening MS-related immune dysregulationM50, 51. Clinicians should be highly aware of this and routine screening may be of value. Prompt treatment has to be offered should depression be found.

ConclusionDepression is common in the population with MS and warrants a heightened clinical awareness and prompt adequate management with address on the underlying multi-dimensional formulation of its etiological factors. Future research may further shed light on the underlying pathogenesis of both conditions. AcknowledgementThis review article serves as an update based on an assignment as part of the academic requirement of the Master of Science in Clinical Neuropsychiatry, University of Birmingham in 2015. The author would like to express her genuine gratitude to Professor Hugh Rickards and Professor Andrea Cavanna on their guidance throughout this course.

Evelyn KY Wong,MBChB, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry) Correspondence to:Dr Evelyn KY Wong, Department of Psychiatry, United Christian

Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong SAR.

References

|

|