|

December 2018, Volume 40, No. 4

|

Case Report

|

Mouth pain - 2 cases of significant adverse drug reactionsChris KV Chau 周家偉 HK Pract 2018;40:118-122 SummaryMouth pain is a very common complaint in patients visiting primary care clinics1. This can be very distressing for the patients and affect their health significantly. Thorough history taking and clinical examination can help physicians to identify such cases and be on the alert for more serious underlying problems including serious adverse drug reactions. 摘要到訪基層醫療診所的患者中,口腔疼痛是非常普遍的 健康問題1,卻可以對患者造成很大的壓力,並顯著地影響 患者的健康。醫生對患者全面地查問病歷和進行臨床檢查 能有助檢視潛在較嚴重的問題,包括藥物不良反應。 IntroductionMouth pain is commonly encountered in patients visiting primary care clinics.1 Poor oral dietary intake resulting from pain during eating can be very distressing and affects patients’ health significantly. Thorough history taking and clinical examination help us to delineate cases and those with serious underlying problems. The following 2 cases illustrate how important it is to have high suspicion on drug related causes. Case no. 1IntroductionA 44-year-old hypertensive lady had gum swelling and pain for a year. She reported that the swelling occurred after just a trivial injury in her mouth. Symptoms affected her eating and appearance making her feel depressed. Clinical historyThe patient had hypertension for 5 years and was followed up in a GOPC. She was first put on betablocker and later amlodipine (a calcium channel blocker) was added. The dose of amlodipine was stepped up from 5 mg to 10 mg daily for blood pressure control. After 3 months, she started to notice gum pain and contact bleeding near her front teeth. Physical examination showed that her gum was inflamed and lobulated lesions were seen around her incisors (Photo 1). Blood tests results were essentially normal except that she had Thalassemia trait. Given the temporal sequence of symptoms which appeared after stepping up the drug, amlodipine induced gum hyperplasia was suspected. Amlodipine was then reduced stepwise and totally replaced by ACE inhibitors over the next 2 weeks. Her gum condition was reviewed at every visit. Gum pain gradually reduced and she could eat normally 6 weeks after amlodipine was stopped.

DiscussionDrug–induced gingival overgrowth (DIGO) has been well-known in patients taking calcium channel blockers. Prevalence of DIGO due to nifedipine (6.3%), verapamil (4.1%) and amlodipine (1.3 - 3.3%) had been reported in overseas studies.2,3,4,5 Other drugs that are found to cause gum hyperplasia include phenytoin and cyclosporine. Pathogenesis is not fully understood. Histologically, DIGO shows an increase in the number of fibroblasts in gingival connective tissues.5 Mast cells and inflammatory cytokines have a synergistic effect in the enhancement of the collagen synthesis by gingival fibroblasts. DIGO can present as increased soft tissue growth and may be lobulated in appearance.6,7 Local factors causing DIGO include plaque, poor oral hygiene and ill-fitting denture, as well as high doses of medication which are associated with increased risk of drug induced gum hyperplasia.8,9 Lesson learnedWe should raise our awareness and review drug history promptly in hypertensive patients presenting with persistent gum pain. Withdrawal of suspected drug and substitution with other anti-hypertensive medicine is the treatment regimen.10 Referral to dentists for further assessment and management in resistant cases is deemed necessary. Good oral condition may help reduce risk of gum hyperplasia in patients with concurrent use of amlodipine.

References:

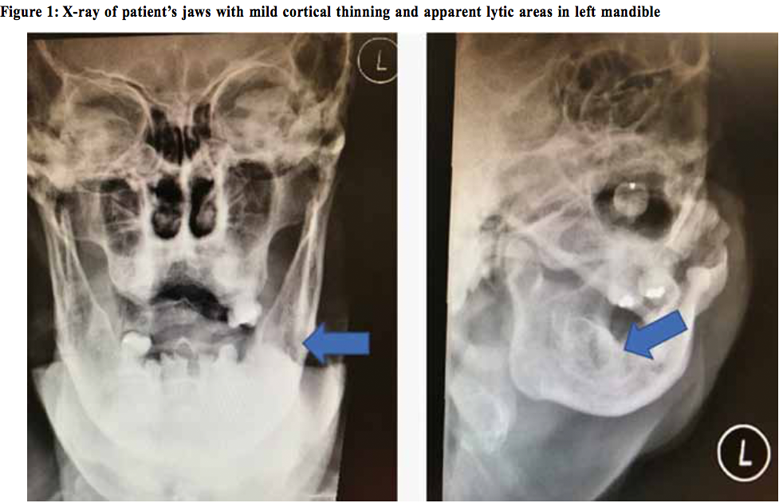

Case no. 2BackgroundAn 81-year-old lady was followed up in GOPC for hypertension (HT), diabetes (DM), lipid disorder and cerebral vascular accident for more than 10 years. She also had dementia and osteoporosis, for which she was being followed up by other specialists. She was a chronic smoker and she lived with her maid. Clinical historyAt one routine consultation for HT and DM, she reported she had pain on her face near her left cheek for 2 weeks. The pain was aggravated on chewing and she lost some weight due to poor appetite. Physical examination showed that her gum was swollen in the molar region of her left lower jaw. The patient was treated as having gingivitis and a course of antibiotics was prescribed. History revealed that she was put on alendronate for treating osteoporosis 2 months earlier. As side effects of alendronate could be the cause of her jaw pain, she was followed up for the jaw swelling and pain by us. One week later, while her cheek swelling was subsiding following the antibiotics, and her appetite improving and she could tolerate small frequent meals, there was persistent pain in her left mandible. Physical examination showed the gum in the molar region was less swollen, but there was tenderness in the left mandible on the inner side of her mouth. The masseter muscle was normal. No trigger point of pain on her face was elicited and the skin was normal. On further review of her drug history, her relative told us that there was no more alendronate left at home because the patient had taken the medicine on daily basis for 2 weeks instead of weekly dose. Overuse of alendronate resulting in bone necrosis was highly suspected. X-ray was taken which showed mild sclerotic changes in the left mandible (Figure 1). The patient was referred to maxillofacial surgery unit for assessment of probable osteonecrosis.

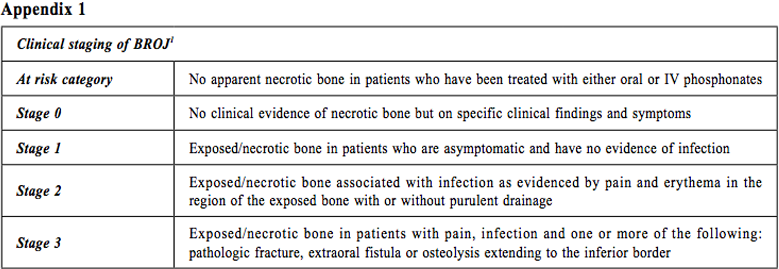

Examination by dental surgeons showed pustular discharge from the left residual ridge near the lingular area. Diagnosis of stage 2 (Appendix 1) medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw was confirmed. The patient was subsequently followed up in the dental department. Several courses of antibiotic were prescribed to treat the recurrent infection. Surgical debridement would be the treatment of choice if the condition was not under control with conservative treatment.

DiscussionThis is probably the first reported case of osteonecrosis of jaw bone, due to alendronate overdose in Hong Kong. Alendronates are bisphosphonates which hamper bone resorption by reducing the activity of osteoclasts. Oral drugs can be used to treat and prevent osteoporosis of various causes as well as Paget’s disease while intravenous drugs are used to reduce symptoms and complications associated with bone metastasis in cancer patients. Apart from the more recognised gastrooesophageal symptoms and those of hypocalcaemia, they are also related to a rare but serious side effect2: osteonecrosis of the maxillary and mandibular bones. Cases of bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) were first reported in 20033 among patients with cancer who received high dose intravenous medication4,5; while around 5% of cases were those receiving low-dose bisphosphonate therapy. Literature showed that the estimated incidence was about 1-2 % at 36 months exposure in oncology patients receiving high dose bisphosphonate intravenously. In osteoporotic patients, it is rare with an estimated incidence of ~1 to 69 cases per 100,000 person-year of exposure.6,7,8,9 In Hong Kong, a recent study10 on the prevalence of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw showed that the prevalence was 0.31% with a frequency of 73.5 cases per 100 000 person-years of oral bisphosphonate treatment, which was higher than the overseas reported figures and about three times that of the United States. It is not known whether and how many cases were related to medication overdose. The median time to onset was 24 months. The exact mechanism is still unknown. It is believed that bisphosphonates cause imbalance of remodelling process that results in impaired osteoclast function. However, if dead and dying osteoblasts are not removed adequately, the congested capillary network in the bone cannot be maintained, resulting in bone necrosis at the site.11 The jaw is more susceptible to osteonecrosis because it has higher cellular turnover than other bones and also because its terminal circulation renders it from ischaemic condition more easily.12 By far, there is no evidence from randomised controlled trials to guide the management of phosphonate-related osteonecrosis. The standard care includes surgery, antibiotics and use of rinse solution. Hyperbaric oxygen as an adjuvant has not been shown to have added benefit. Besides pain control, patients may require dental manipulations including debridement and antibiotic treatment for recurrent infection. Although evidence-based management plan is not available, there are practice guidelines for prevention; and early detection of the osteonecrosis of jaw.13,14,15,16 Firstly, it is important to identify patients at high risk. Risk factors include elderly, female gender, poor dental condition such as local infection or inflammation, dental procedures such as extraction, history of DM, smoking, alcohol consumption and post irradiation of head and neck region. Secondly, it is advisable to reduce the opportunity for dental infection by keeping good oral hygiene and avoiding invasive treatment as far as possible. Always consider oral and dental checkup and completion of any major oral procedures before initiating any drug treatment is also recommended at some centres. Regarding the prognosis of alendronate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws, a 4-year cohort study17 has shown that early detection of lesions and prevention of further extension are of paramount importance in having better clinical outcome. Full recovery from BRONJ was observed in nearly half of the patients in 6 months in the study. ConclusionIn using bisphosphonates on elderly patients with osteoporosis, one should be very cautious because any misuse of this medication can result in serious long-term complication. Not only bone and osteoporosis specialists as well as dentists, but also general practitioners should be careful when managing patients who complains of mouth pain; especially dealing with the elderly who are on drug treatment for osteoporosis. Thorough medical and drug history on compliance and drug administration, especially of bisphosphonate, in the elderly should always be enquired about.

Chris KV Chau, MPH (Johns Hopkins), FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Community medicine)

Correspondence to: Dr Chris KV Chau, 6/F, Tsan Yuk Hospital, Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|