|

December 2018, Volume 40, No. 4

|

Original Article

|

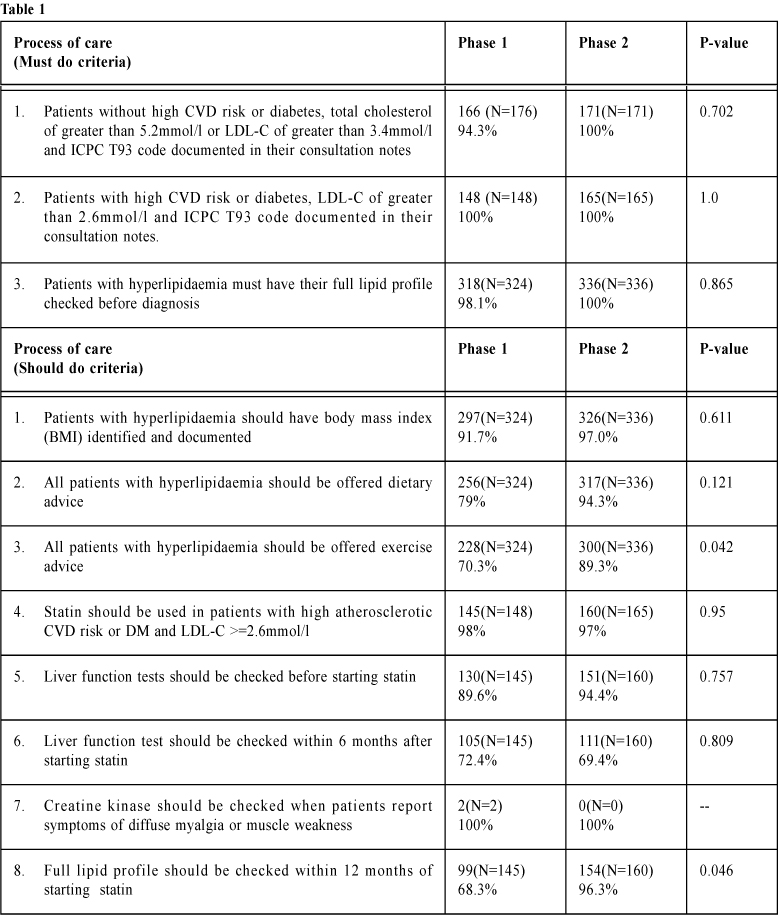

Outcomes of a clinical audit of hyperlipidaemia in a Hong Kong general outpatient clinicDavid CH Cheung 張志康 HK Pract 2018;40:101-108 SummaryBackground: Methods: This study was a clinical audit in 2 phases. Criteria were set up to include patients with hyperlipidaemia for interventions of 12 months duration. Interventions included discussion with doctors, nurses and clerical staff on patient care management and provision of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods to our patients. The effects of these interventions were shown as the percentage of patients who were able to achieve the targeted LDL-C levels according to the different cardiovascular risk groups and the percentage of patients who could maintain and achieve a low cardiovascular disease risk profile at the end of the intervention. Results: 324 and 336 patients with hyperlipidaemia were recruited in phase 1 and 2 respectively for this audit. 100% of patients fulfilled all “Must do” criteria and more than 70% of patients fulfilled all “Should do” criteria, except criteria 6. As for the outcome criteria, more than 70% of patients fulfilled all of the criteria. Criteria 3 (p=0.042) & 8 (p=0.046) of “Should do” criteria achieved statistically significance while criteria 1 (p=0.000009), 2 (p=0.026) and 4 (p=0.018) of the outcome criteria achieved statistically significance. Conclusion: Among all patients with hyperlipidaemia undergoing interventions, there were improvements in the various clinical outcomes with statistically significance. In long run, patients could benefit from reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Keywords: Hyperlipidaemia, cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, statin, primary care 摘要背景: 方法:本研究在普通科門診,分別在兩段時間進行臨床審 計。研究為符合條件的高脂血症病人,在診治時加入特設 程序,為期12個月。該介入程序包括與醫生,護士或文書 職員討論病人在照顧上的處理,及向他們提供藥物和非藥 物的治療方法。介入後的成果將反映在不同心血管疾病風 險組別中,能夠成功達至目標LDL-C水平的比率,以及當 完成介入程序時,仍能保持或可降至低心血管疾病風險水 平的比率。 結果: 分別有3 2 4和3 3 6名高脂血症病人被納入第一期和 第二期的審計。全部病人均符合「需要的診斷條件」。在 「應進行項目」上,除第6項外,70%以上病人符合在方案 中的所有要求。至於在「介入後成效」方面,70%以上病 人能達到需要的全部目標。在比較第一和第二次審計時的 「應進行項目」,項目3和項目8的P值為0.042和0.046;而 在「介入後成果」,項目1、2和4的P值分別為0.000009, 0.026和0.018。此等都達到統計學上的明顯水平。 結論:在診治時加入特設程序的高脂血症病人,其各種臨 床效果均可得到明顯改善。長遠而言,病人可因減少心血 管疾病和死亡而獲裨益。 關鍵字:高脂血症、心血管疾病風險、他汀類藥物、基層醫療 IntroductionHyperlipidaemia is a disease with both a high incidence and prevalence rate in Hong Kong.1-2 This condition is associated with a high morbidity and mortality. The complications of hyperlipidaemia are preventable via proper lifestyle modifications and drug treatment. Health care services in Hong Kong are of high standards and delivered with high efficiency. However, our healthcare system is now facing major challenges caused by a rapidly aging population. There will be an increasing number of chronic disease patients as our population ages, including patients with hyperlipidaemia. There is a need to develop more proactive, continuing, integrated, and comprehensive services at the primary care level with better coordination among different healthcare providers. In Hong Kong, the prevalence of high cholesterol for people aged 15 to 84 was 49.5% in the 2014/15 population health survey.3 According to the World Health Organisation data retrieved in 2017 , cardiovascular disease took the lives of 17.7 million people every year, i.e. 31% of all global deaths.4 In Hong Kong, heart disease and stroke ranked as the third and fourth causes of death in 2013. In that year, amongst the 43,399 registered deaths in Hong Kong, diseases of heart contributed to 5,814 of the mortalities, and stroke, 3,241.5 The author is working in one of the general outpatient clinics (GOPC) provided by the Hospital Authority, providing a wide range of services for a population of 290,240 patients. According to our clinic’s statistics, hyperlipidaemia is the third most commonly encountered disease, preceded by hypertension and diabetes mellitus. There are 5 consultation rooms. On average, each doctor needs to see about 60 patients daily. No standard hyperlipidaemia management was ever established in our clinic. Initiating a systematic and have audit activity organised in our clinic is the best way to evaluate the current standard of practice and find an effective hyperlipidaemia management so that cardiovascular disease risk could be minimised. To this day, many well established guidelines are available, including the National Cholesterol Education Programme, the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) 2004, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2008, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009, and the Joint British Societies’ Guideline (JBS 2) 2005.6,7,8 The Joint British Societies’ Guideline was adopted in this audit because this guideline and the included cardiovascular disease assessment charts are currently adopted by the Hospital Authority for the diagnosis of hyperlipidaemia and evaluation of a patient’s 10-years cardiovascular risks. It was therefore used in this audit in order to meet international standards while providing an efficient hyperlipidaemia management programme. Statin should be used in all patients who had been evaluated to have high cardiovascular risk and all those with diabetes mellitus (DM). A population cohort study which was carried out in 2017 showed that statin was effective in the primary prevention of patients with cardiovascular risks.9 MethodsInclusion and exclusion criteria were set up in order to select the most appropriate patients for this audit. The inclusion criteria included all patients with a diagnosis of hyperlipidaemia, and who were being regularly followed up in our GOPC during the audit period. The exclusion criteria were patients with hyperlipidaemia but were being followed up at the specialist clinics, and patients with hypertriglyceridaemia but with a normal total cholesterol or LDL cholesterol level [TC <5.2 mmol/L (<200mg/dL) or LDL <3.4 mmol/L (<130mg/dL)] and patients who defaulted follow up during the period of the audit. High CVD risk is defined as patients who have a 10-year cardiovascular disease risk of 20% or more, or the presence of DM; according to the Joint British Societies' guideline on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. We focused particularly on those patients with high CVD risk and DM patients with hyperlipidaemia because they are the 2 groups of patients who are the most vulnerable to future cardiovascular disease events. Thus, the outcome of this audit is to bring them to a level that their LDL levels can reach the target level in accordance to their CVD risk factors [i.e. for patients with hyperlipidaemia and without CVD or DM, the target LDL-C should be < 3.4mmol/L; for patient with hyperlipidaemia and CVD or DM, the target LDL-C should be < 2.6mmol/L]. In this way, their cardiovascular disease events can be minimised. For the established CVD/DM group, statin should be used in addition to lifestyle modification according to the current guidelines, while for those without CVD/DM group, lifestyle modification and body weight control should be the mainstay of their management. Patients in the low CVD risk group, defined as those having a 10-year CVD risk below 10%, will be observed at the end of audit to see if the risk level can be maintained below this 10%, while those in the high CVD risk group, defined as those having a 10-year CVD risk equal or above 20%, will be observed at the end of audit to see if the risk level can be reduced to below 10%. Must do, and should do, criteriaIn order to improve the management of hyperlipidaemia and incorporate these measures into daily practice, “must do” criteria and “should do” criteria for the processes of care were set up as follows: Must Do Criteria

Outcome criteriaAs for the outcome of hyperlipidaemia management, criteria were set up as follows:

The “Must do” criteria were targeted at 100% achievement, and the “Should do” criteria were targeted at 70% achievement, based on expert opinion. The outcome criteria were targeted at 70% achievement, based on expert opinion. Data collection methodA patient list of the clinic with the registered ICPC (International Classification of Primary Care) coded as lipid disorder (T93) was retrieved from the Clinical Management System (CMS) of the Hospital Authority. The sample size was calculated via the computer programme – sample size calculator.24 Randomised sampling was done via the tool - Research Randomiser.25 Medical records of the selected samples were retrieved from the Clinical Management System (CMS) of the Hospital Authority. For each patient, the author traced the record back to their first consultation with the diagnosis of hyperlipidaemia at our general out-patient clinic and reviewed each subsequent consultation note, manually. Data were entered into a data collection file in Microsoft Excel 2010 Format. AuditPhase 1 AuditA patient list with their registered ICPC (International Classification of Primary Care) coded as lipid disorder (T93) during the period 1st Sept 2012 to 1st Sept 2013 was retrieved from the Clinical Management System (CMS). There were 2,647 patients registered in our clinic. The sample size was calculated using the computer programme – sample size calculator.24 Based on the population size of 2,647, the calculated target sample was 336, which could achieve the confidence level of 95%, with the standards obtained within +/- 5% from the actual value (i.e. to allow 5% error). 324 patients were selected from the population of hyperlipidaemia after exclusion. InterventionsThe results of phase 1 audit were presented in the regular monthly clinic meeting at which all medical colleagues were obliged to attend. An extra 1 hour special talk was arranged with all medical, nursing and clerical staffs at which hyperlipidaemia management was updated. Strategies to improve our standard of care for lipid problem were discussed, agreed and implemented by all grades of staffs. 1. Diagnosis of hyperlipidaemia and segregation of patients into high/low cardiovascular risk groupDoctors were informed about the deficiencies of failing to code hyperlipidaemia properly and the reasons behind this. The Joint British Societies’ cardiovascular disease risk prediction chart was placed in each of the consultation room work desks. This provided easy reference for physicians when it comes to calculating a patient’s 10-year CVD risk. 2. Non - pharmacological management of hyperlipidaemiaBoth doctors and nurses would be responsible to provide therapeutic lifestyle changes which include dietary control and exercise. In view of the limited consultation time during a busy day, doctors were encouraged to refer patients to nurses for providing therapeutic lifestyle changes which included dietary control and exercise via a doctor’s management sheet. The sheets, computer printed by clerical staffs, were placed inside the work trays of all the clinic duty doctors’ rooms. Also, patient education pamphlets were made available in the trays and refilled by clerical staffs. Referral of patients to a dietitian or to a patient empowerment programme could be made via the Clinical Management System of Hospital Authority in the computer. 3. Pharmacological management of hyperlipidaemiaA flowchart of drug management of hyperlipidaemia was attached to each consultation room in the hope that this would improve the efficiency when managing patients with hyperlipidaemia. Simvastatin was available in our pharmacy and our pharmacists would confirm the justification of using statin only for high cardiovascular risk patients or patients with diabetes mellitus. Reminders were placed at each of the clinic doctor’s desk to increase the awareness of the need to check liver function before starting statin and rechecking this within 6 months after its commencement as well as a full lipid profile within 12 months. If patients complained of myalgia and muscle weakness, then creatine kinase would be checked to look for evidence of myositis. Phase 2 AuditA patient list with the registered ICPC (International Classification of Primary Care) coded as lipid disorder (T93) during the period 1st Sept 2013 to 1st Sept 2014 was retrieved from the Clinical Management System (CMS). There were 3,165 patients registered in our clinic. The sample size was calculated via the computer programme – sample size calculator.24 Based on the population size of 3,165, the calculated target sample was 343 in order to achieve a confidence level of 95%, with the standards being within +/- 5% from the actual value (i.e. to allow 5% error). 336 patients were selected from the population of hyperlipidaemia after exclusion. ResultsIn phase 1 audit, there were altogether 324 patients recruited for this audit. There were 124 males and 200 females. The ages of the patients ranged from 32 - 96, with a mean age of 66. Amongst the 324 patients, 47 patients had CHD (or CHD equivalents), and 111 patients had diabetes mellitus (DM). In phase 2, there were altogether 336 patients recruited. There were 127 males and 209 female. The ages of the patients ranged from 35 -101, with a mean age of 68.4. Amongst the 336 patients, 49 patients had CHD (or CHD equivalents), and 122 patients had diabetes mellitus (DM). Table 1 showed the “Must do” and “Should do” criteria under the processes of care and Table 2 showed the outcome criteria.

DiscussionIn phase 1 of this audit, only criteria 2, 100% fulfilled the "must do" criteria; and criteria 1 to 7, 70% fulfilled the "should do" criteria. Concerning clinical outcome, a standard of 70% or above fulfilled criteria 3 only. All other criteria failed to attain the required standards. In phase 2 of the audit, all “must do” criteria had been fulfilled and most “should do” criteria had been fulfilled with the exception of criteria 6, which failed to attain the standard of 70% or above. This could possibly be due to the patient’s preference of wanting to defer a recheck of their liver function till the next risk assessment and management programme (RAMP) test within 12 months. In “should do” criteria 3 and 8, statistically significant improvement (p-value < 0.05) was achieved. All 4 clinical outcome criteria had fulfilled the standard of 70% or above. Also, clinical outcomes 1, 2 and 4 achieved statistically significant improvement (P-value < 0.05) as well. That means both the process of care criteria and the clinical outcome criteria can achieve successful improvements after implementation of interventions. The success of the interventions included: 1. Diagnosis of hyperlipidaemiaAfter reviewing hyperlipidaemia guidelines with clinic doctors, their feedback from this was that they learned more about the current guidelines and recommendations. They agreed to put down ICPC code as the diagnosis of hyperlipidaemia and full lipid profile was performed for all patients. Therefore the “must do” criteria 1 and 3 showed improvement in phase 2, reaching the targeted 100% as compared to phase 1. 2. Risk factorsAfter reviewing the various recommendations, the clinic doctors showed an improved awareness of risk factors management. The consultation notes documented more details on risk factor management. The support from nursing staff and allied health workers had actually helped patients in terms of blood pressure control, body weight management, dietary and exercise advice. Therefore the “should do” criteria 1 - 3 showed improvement in phase 2 as compared to phase 1. 3. Dealing with hyperlipidaemiaDoctors showed an improved awareness about indications and medical treatment of hyperlipidaemia. They were also responsible for making sure that liver function tests had to be checked before starting statin. The drug side-effects screening had been closely monitored and documented. Therefore, the “should do” in criteria 5 and 8 showed improvement in phase 2 as compared to phase 1. 4. Following upDoctors demonstrated an improved awareness on the treatment goals for different groups of patients thus improving their overall outcomes. This was shown with the clinical outcome criteria of more than 70% of both high and low risk patients having achieved the targeted LDL-C level. Those patients who were initially labelled with being of a high cardiovascular disease risk had their status changed to having a low cardiovascular risk: while low cardiovascular disease risk patients remained unchanged by the end of this audit.

Suggestions for improvementsIn order to improve this audit further and future audits, a higher standard of percentage in “Should do” and “outcome criteria” should be used and protocols should be regularly reviewed to confirm the latest lipid guideline management was updated and adhered to by all clinical staff. This is with the aim of minimising the long term cardiovascular events for all patients with hyperlipidaemia. LimitationsThis audit only focuses on the management of hyperlipidaemia. Patients’ drug adherence, management of hypertension, management of diabetes, smoking cessation and utilisation of allied health services were all factors contributing to a patient’s cardiovascular outcome but these were not fully assessed in this audit. From the doctors’ perspective, expected and unexpected turnover of staff may have contributed to interventions with this audit. As doctors were required to serve different clinics within the same Hospital Authority cluster, this may contribute to the breakdown of a patient’s continuity of care. ConclusionIn conclusion, statistically significant improvements in some aspect of hyperlipidaemia management for patients who attended this general outpatient clinic were found. As a result, patients would benefit from an improved quality of care, as well as achieving a reduction in their cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

David CH Cheung, MBBS (HKU), FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Correspondence to: Dr David CH Cheung, 10 Aberdeen Reservoir Road, Aberdeen, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|