|

June 2018, Volume 40, No. 2

|

Original Article

|

A study on the prevalence of multi - morbidities of diseases and utilisation of public healthcare services in the New Territories West area of Hong KongTsun-kit Chu 朱晉傑,Phyllis Lau 廖明玉,Ronald SY Cheng 鄭世業,Man-li Chan 陳萬里,Jun Liang 梁峻 HK Pract 2018;40:43-50 SummaryObjectives: Design: Retrospective cross-sectional study by reviewing the electronic medical records. Subjects: A random sample of 382 adult patients aged 40 or above attending the service’s public primary care in 2012. Main outcome measures: Prevalence of multi-morbidity (defined as presence of 2 or more) , of chronic conditions associated with the utilisation of public healthcare services by those patients with multimorbidity.

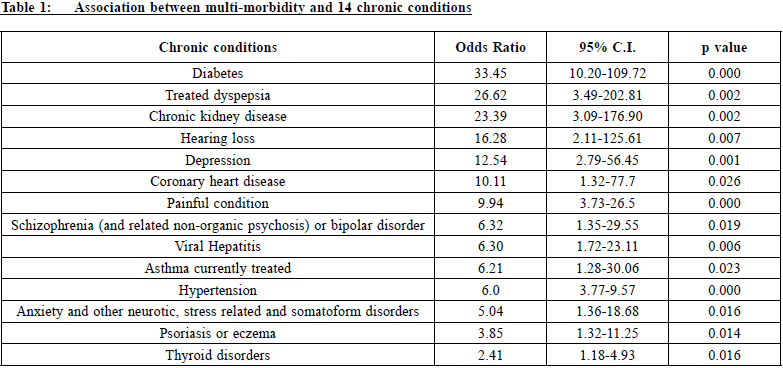

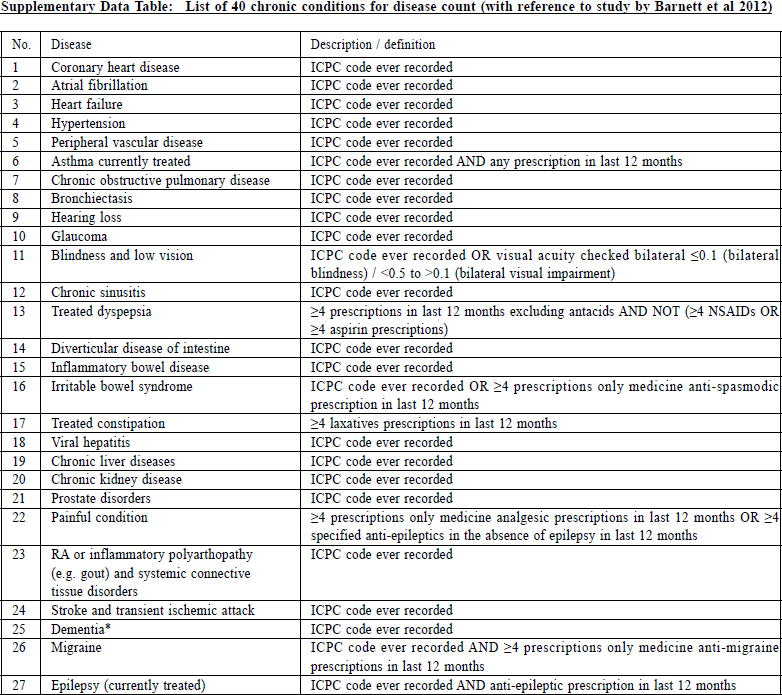

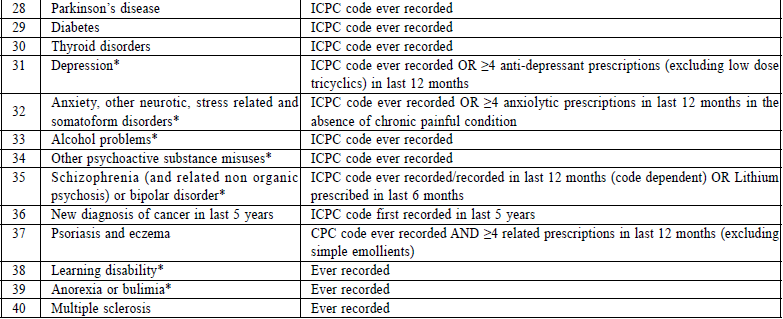

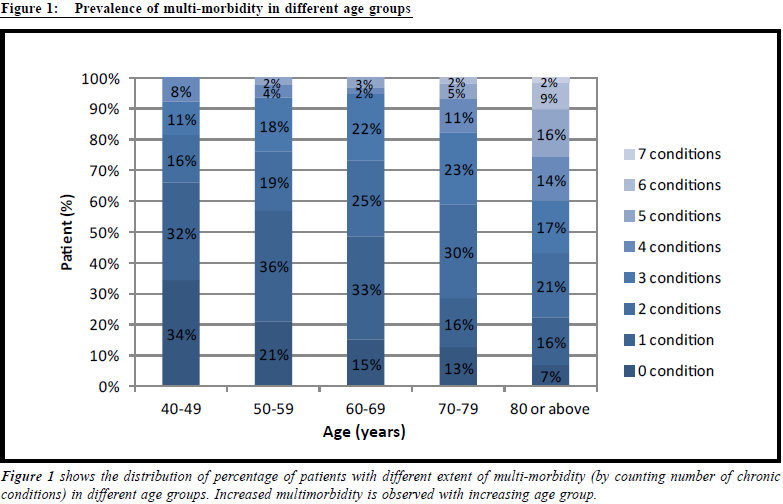

Results: The prevalence of multi-morbidity in our sample was 54%. Fourteen chronic conditions were associated with multi-morbidity and diabetes had the strongest association. Adjusted for age, sex and presence of psychiatric illness, increased number of morbidity was associated with increased specialist outpatient clinic attendance and casualty visits, as well as hospital admissions. Conclusion: Multi-morbidity was common and most frequently seen among patients with diabetes in the public primary care clinics in Hong Kong. It also appeared to be associated with higher health care utilisation. Keywords: Multi-morbidity, primary health care, utilisation, public services 摘要目的: 設計: 借助回顧電子病歷的回顧性橫斷面研究。 對象:2012年曾到公立基層醫療機構就醫的382名40歲及以 上成人患者的隨機樣本。 主要測量內容:多病共存(指患有2種及以上慢性疾病)患 病率、多病共存相關的慢性疾病、以及多病共存患者使用公 立基層醫療衛生服務的情況。 結果:本研究樣本人群的多病共存患病率為54%。十四種慢 性疾病與多病共存相關,而糖尿病的關聯最為密切。對年 齡、性別和精神疾病進行調整後,多病共存的增多與專科門 診及急診室就醫增加和住院增加存在關聯。 結論: 多病共存很常見,在香港公立基層醫療診所的糖尿病 患者中最常見。同時與較高的醫療衛生服務使用存在關聯。 關鍵字:多病共存,基層醫療,服務使用,公立服務 IntroductionMulti-morbidity is increasingly dealt with among the primary care population globally.1-5 It is particularly prevalent in older adults and more common in socially deprived areas than affluent areas.5-7 It has been shown that multi-morbidity creates a heavy burden for the healthcare system with increased healthcare cost and utilisation.8-11 This impairs the physical functioning and quality of life of individuals.12 Identification of multimorbidity prevalence and health care utilisation is the first step in the development of targeted interventions to improve health outcomes.13 Although multi-morbidity measurement varies among studies, there are established multi-morbidity indices available for epidemiological measurement.14-16 Epidemiological data has shown that the prevalence of multi-morbidities and the proportion of public and private healthcare expenditure varied among different populations under different healthcare funding systems.17-18 Association between multi-morbidity and a countries’ GDP per capita has been demonstrated.17 The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China has a dual-track healthcare system encompassing public and private sectors.19 The public healthcare system provides a safety net for healthcare needs of the whole population. Under the Hospital Authority, the heavily subsidised public sector served around 90% of secondary care in hospital and provided approximately 30% of primary healthcare for the population. The imbalance of the dual-track system would continue or worsen as more patients are attracted into the public system because of escalating costs of chronic disease management and the ageing population.20 The New Territories, is one of the 3 major regions of Hong Kong, making up more than 85% of the city’s land area, and containing about half of the city’s population. The New Territories West area of Hong Kong (NTWHK) had a population of 1,006,075 in 2011. It was one of the most socioeconomically deprived areas in the locality. As indicated by the 2011 Hong Kong Population census21, the median monthly domestic household income of this area was at least 10% lower than that of the average of all other districts in Hong Kong. The population in this area was served by 7 public primary care clinics with a total of 729,576 attendances for the year 2011-2012.22 The target patients included elders, low-income individuals, and patients with chronic illness for both acute episodic illness and follow up of chronic conditions. It was estimated that around 30% of primary care consultations in Hong Kong23 were provided by public clinics. Only 2 public hospitals, provided healthcare service for the NTWHK in 2012. With an increasing demand for public healthcare service in Hong Kong, there was a need to review our service utilisation and to develop measures for a sustainable service for patients with multimorbidities. The objectives of this study were to identify the multi-morbidity prevalence among patients attending the public primary care clinics in NTWHK, and to investigate association between multi-morbidity and utilisation of public healthcare services. MethodsThis was a retrospective cross-sectional study using the existing database of electronic medical records in the 7 primary care clinics (General Outpatient Clinics (GOPCs)) in NTWHK. Medical records of adult patients aged 40 or above who attended for medical consultation in the 7 clinics from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2012 were included. The age cut-off was selected as previous epidemiological data showed there was a low estimated prevalence of multi-morbidity before age 40 while there was a sharp rise in prevalence followed by a plateau with age approaching 70.25 Two investigators independently reviewed these medical records and collected data such as disease coding, prescription records and consultation notes. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Patient demographics including age, gender, and payment status for service were also collected. The reason for collecting data on patient payment status was because patients who needed government subsidies or their social security allowance to waive consultation fee would partially reflect an individuals’ socioeconomic status. This study adopted the most inclusive and simplest definition of multi-morbidity which is the co-occurrence of 2 or more chronic diseases within one person in a specific period of time.15 Chronicity was defined and based on the majority of published definitions of chronic conditions, which included duration that the condition lasted, or was expected to last, at least 6 months duration, pattern of recurrence or deterioration, poor prognosis, and producing consequences or sequelae that impact on the individual’s quality of life.24 Multi-morbidity was determined using clinician-rated disease count and the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS). Clinician-rated disease count was derived from medical records. It is the most commonly used measure of multi-morbidity and has been used in relation to health outcomes in other studies.25 However, it does not take into account the weighting of diseases with respect to severity or prognosis. Morbidities included were based on a large scale population-based cohort study on multi-morbidity5 which covered 40 important chronic conditions, including those conditions that were identified as important for health service planning by the Food and Health Bureau of Hong Kong Government26,27 (Supplementary Data Table S1). CIRS measured multi-morbidity which included weighting of diseases in order to assess the burden of chronic illnesses in the primary care setting28, and as such it was a better predictor of health related quality of life and psychological distress than simple disease count.29 The outcome parameters of utilisation of public healthcare service were the number of visits for medical consultations in the primary and secondary care outpatient clinics, casualty attendance and hospital admission episodes. Sample size was calculated using a Confidence Level of 95%. The calculated sample size was 384.30 The association between multi-morbidity in different chronic conditions and the utilisation of different public healthcare services were analysed by logistic regression using the statistical software SPSS. ResultsIn total, we reviewed the medical records of 382 patients. Sixty-three percent were female, 55% were aged 60 years or above and 85% did not utilise government assistance for their medical consultation fee. The prevalence of multi-morbidity in this study sample was 54%. Thirty-one percent of them had cooccurrence of 3 or more chronic conditions. 64% of those aged over 80 had 3 or more chronic conditions (Figure 1). Association of multi-morbidity with individual chronic diseases was analysed by binary logistic regression. Fourteen chronic diseases were found to have significant association with multi-morbidity (Table 1). Three of these were mental conditions; diabetes mellitus had the strongest association; and depression and coronary artery disease had the widest range (0 to 6) of number of co-existing chronic conditions. The average disease count was 1.89 (range 0 to 7) per patient and average CIRS score was 3.89 (range 0 to 13) per patient. For patients with multi-morbidity, the mean diseases count was 3.0, compared with 0.62 for those without multi-morbidity (mean difference 2.37, 95% Confidence Interval 2.20 – 2.55); and the mean CIRS score of patients with multi-morbidity was 5.53, compared with 1.99 for patients without multi-morbidity (mean difference 3.52, 95% Confidence Interval 3.12 – 3.94).

Notes: * regarded as mental condition

Notes: * regarded as mental condition

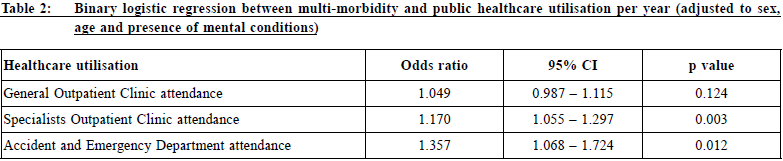

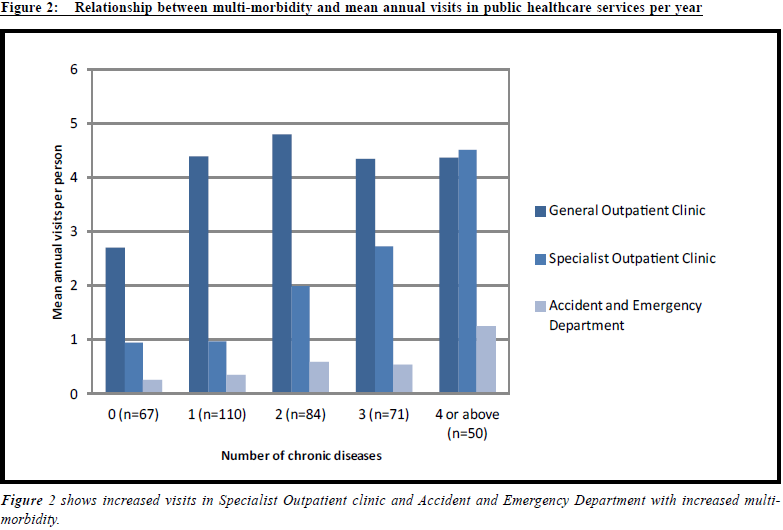

The mean number of medical consultations in public primary care clinics (General Outpatient Clinic), public secondary ambulatory care clinics (Specialist Outpatient Clinic) and public casualty (Accident and Emergency Department) for the study sample were 4.0, 3.27 and 0.91 per year respectively. Figure 2 presents the relationship between multi-morbidity and public healthcare utilisation. Using logistic regression adjusted to age, sex and presence of mental conditions, increased multimorbidity was associated with increased attendance in Accident and Emergency Department and Specialists Outpatient clinics, and increased hospital admission. It did not, however, influence attendance at the General Outpatient Clinics (Table 2). DiscussionMulti-morbidity is prevalent in the public primary care clinics in NTWHK and is consistent with results from overseas studies carried out in family practice or primary care settings.1-5 The burden of multi-morbidity is evident more in the elderly, and is associated with increasing visits to hospital specialists and emergency care. A previous territory-wide study showed that users of General Outpatient clinics were more often female, older, poorer and of the chronically-ill population.32 This was also reflected in our study sample: the female to male ratio was about 3:2; more than half were aged 60 or above; and the majority did not receive government subsidies for their consultation fees. The last demographic result, nevertheless, needs to be interpreted carefully as a single parameter was unlikely to be comprehensive enough to determine the true socioeconomic status of our sample. The previous study conducted by Wong et al32 also included income, education and health insurance coverage in its analysis. It was not possible to extract such information from our retrospective review of patients’ medical records. For this reason, we are unable to determine if prevalence of multi-morbidity and public healthcare utilisation was influenced by the socioeconomic status of our study sample.

Our findings on public healthcare utilisation are similar to those found by overseas studies.8-11,18 The local prevalence of multi-morbidity among patients in the public primary care clinics was associated with more attendance to accident and emergency department and secondary care utilisation. We did not however show that multi-morbidity was associated with more primary care clinic visits as observed in other countries.8 This difference may be attributed to the uniqueness of our Hong Kong healthcare system and its sociocultural background. About 70% of the primary care service in Hong Kong is provided by the private sector, while 90% of secondary and tertiary care is provided in the public sector.31 In Wong et al’s study, almost all the patients who received service in the public primary care clinics had also visited private general practitioners.32 Accessibility to the public primary care service is currently based on a first-comefirst- served telephone booking system with a limitation on the quota availability. This is likely to affect the public primary care service utilisation by patients with multi-morbidity. The “Inverse care law” describes the inverse relationship between the availability of good medical care and the need for it in the population it serves.34-36 A local territory-wide cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of 4,812 elderly (aged 60 and above) showed that there was a mismatch of demand and supply within the mixed economy of private and public healthcare services in Hong Kong, which, in other words, suggested the existence of an 'inverse care law' amongst our elderly citizens.37 Sociocultural factors distinctive to Hong Kong most certainly would affect health seeking behaviour and in turn affected public healthcare utilisation.38 Future qualitative studies are needed to explore the complex service preferences and needs for Hong Kong people with multi-morbidity.

There are limitations in the methodology of this study. Firstly, clinical data was retrospectively collected from review of medical records which might not be comprehensive or entirely accurate. Although the electronic clinical information system of the public healthcare system was well-connected amongst its general outpatient clinics, specialist outpatient clinics and hospital units, no such linkage of medical records existed between the private and public healthcare system at the time of the study. So, there is a potential of missing data when patients with multi-morbidities attended both public and private healthcare services. Secondly, the generalisability of results could be affected by the unclear socioeconomic status of the study sample. The prevalence of multimorbidity multimorbidity might be over-estimated, and thus, not generalisable to the population, because only age 40 or above was recruited in the sample. Finally, this study only estimated the public healthcare utilisation by the number of visits for medical consultation, and did not look into other aspects of healthcare expenditure such as nursing and allied health service, laboratory or diagnostic service utilisation and prescriptions. In addition, the results only represented the situation in public healthcare service, while the prevalence of multi-morbidity among patients with chronic conditions followed up in private healthcare was not assessed. It would be worthwhile to compare the prevalence of multi-morbidity between public and private sectors in future studies. ConclusionMulti-morbidity is commonly encountered in public primary care clinics in Hong Kong. This study identified 14 chronic conditions which are associated with multi-morbidity amongst its patients attending the NTWHK public primary care clinics. Such data would be useful in planning future research on target interventions or services for patients with complex needs. With the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, multi-morbidity and longer life expectancy, there needs to be a paradigm shift in health care delivery from disease-based approach to holistic generalist approach. A system change in integrating primary and secondary healthcare services to reduce hospitalisation and to keep patients ambulatory must be our future direction for a more healthy and sustainable healthcare system in Hong Kong. Acknowledgements:We acknowledged research support from the administrative team of the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, New Territories West Cluster, the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong, and Professor Jane Gunn and her Department of General Practice, the University of Melbourne. This study has been approved by the Cluster Research Ethics Committee of New Territories West Cluster, the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. This study was funded by the departmental resources of the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, New Territories West Cluster, the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. There is no conflict of interest with this study.

Tsun-kit Chu,MSc, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Correspondence to: Dr. Tsun-kit Chu, Associate Consultant, Department of Family

Medicine and Primary Health Care, New Territories West Cluster,

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: chutk2@ha.org.hk

References:

|

|