|

March 2018, Volume 40, No. 1

|

Original Article

|

The efficacy and safety of use of varenicline for smoking cessation: a survey and study on its use by private general practitioners in Hong KongKin-sang Ho 何健生,Helen CH Chan 陳靜嫻,Joe KW Ching 程錦榮 HK Pract 2018;40:3-10 SummaryObjectives:

Design: A retrospective cohort study and a questionnaire survey Subjects: Smokers aged 18 or above in Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs) Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation during the period of 1/1/2015 to 31/10/2016. Main outcome measures: Primary outcome is selfreported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 26th week and secondary outcome is adverse event profiles of varenicline as reported by smokers by case review; discontinuation rates due to adverse event. Survey outcome measure is the attitude and pattern of use of varenicline.

Results: The 7-day point prevalence quit rate on 26th week for smokers on varenicline was 43.2%. There was no serious adverse event on using varenicline. The most commonly reported side effect was gastrointestinal disturbances. As to the survey on the use of varenicline by private general practitioners, 50% of doctors had never used the drug before. 83.9% of them did not have training on motivational interview. The average time affordable for smoking cessation counselling was 8.3 minutes (SD=4.9). Conclusion: Varenicline is an effective drug for smoking cessation and is generally safe to use. It is preferable to monitor the mood during smoking cessation while using the drug. There are some barriers for general practitioners to provide smoking cessation service. Referral to smokers’ specialist clinic for smoking cessation may be considered if needed. Keywords: Smoking cessation, varenicline, general practitioners 摘要目的:

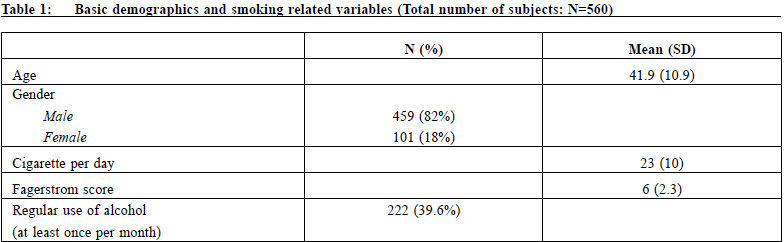

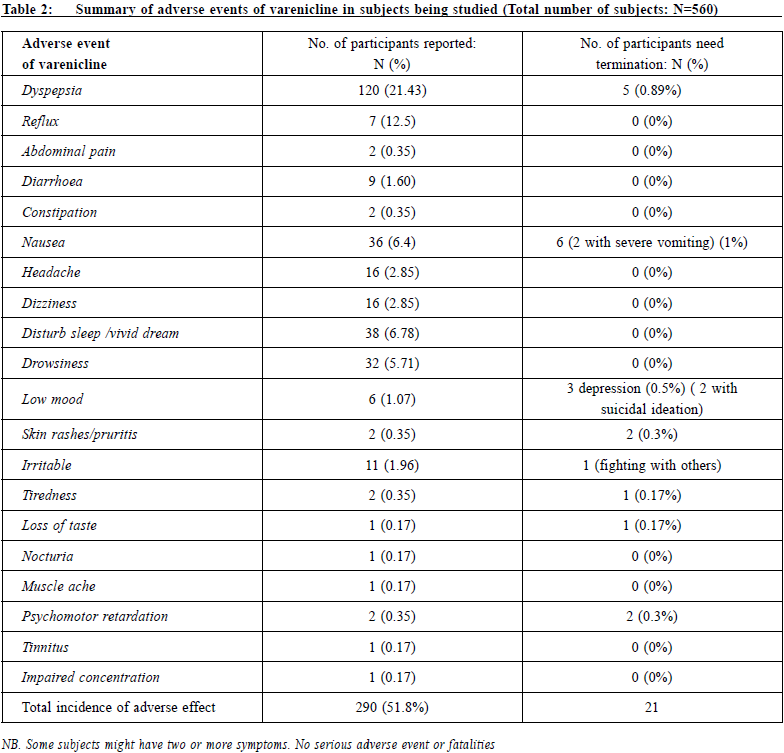

設計: 回顧性佇列研究和問卷調查 對象:2015年1月1日-2016年10月31日期間東華三院綜合戒 煙中心18歲及以上吸煙者 主要測量內容:主要指標是第26周時自我報告的7天時點戒 煙率;次要指標是病例回顧中吸煙者報告的伐倫克林相關 不良事件的情況,以及因為不良事件而複吸的情況。調查 測量內容是對使用伐倫克林的態度和使用規律。 結果:吸煙者使用伐倫克林第2 6 周的7 天時點戒煙率為 43.2%。未見使用伐倫克林導致的嚴重不良事件。最常報告 的不良反應是胃腸道功能紊亂。對私人開業全科醫生使用 伐倫克林的調查發現,50%的醫生以前從未使用過該藥; 83.9%的醫生未接受過動機性訪談的培訓。用於戒煙諮詢的 平均時間為8.3分鐘(SD=4.9)。 結論: 伐倫克林是一種有效的戒煙藥,通常使用起來也較安 全。藥物戒煙期間最好監測情緒。全科醫生提供戒煙服務尚 存在一些障礙。必要時,可考慮轉診給戒煙專家門診。 關鍵字:戒煙,伐倫克林,全科醫生 IntroductionSmoking is a well-known risk factor of morbidity and mortality caused by cancers, cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases. Although the prevalence of smoking in Hong Kong has dropped to 10.5% in the recent decade and, according to latest statistical reports, is one of the lowest among the world and Asian countries1; it is still the cause of half of all deaths among Chinese smokers aged 65 years or above.2 47% of smokers in Hong Kong have tried or wanted to give up smoking, and some of them quit by self-determination.3 However, unaided quit attempts have low success rates of 3-5%.4 Smoking cessation treatments are among the most cost effective disease prevention interventions available. Licensed pharmacological smoking cessation therapies, such as nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline, are readily available to assist smokers in smoking cessation. Varenicline, a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, has been used in Hong Kong for around 10 years since its licensing, and it has remained one of the main oral medications for smoking cessation. Overseas controlled trials have well demonstrated its efficacy over placebo and the abstinence rate at 6-month post-quit is about 33%.,5-8 However, participants included in these initial trials were predominantly Caucasian. Less than 3% of participants were of Asian origin. Local Hong Kong data is lacking. There are concerns about the safety of varenicline.9-10 The drug had been linked to a wide range of side effects, increase in cardiovascular risks, severe skin reactions, seizures, psychosis, aggression and suicide. Since 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has required the adding of a black box warning to the labelling of varenicline about its neuropsychiatric side effects.11 However, the data in our locality is lacking. On 1st January 2007, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government enacted the Smoking (Public Health) Ordinance and on 25th February 2009, tobacco tax was increased by 50%. In 2009, the Tung WahGroup of Hospitals (TWGHs) was commissioned by the Hong Kong SAR Government to provide a community based smoking cessation service in Hong Kong. The Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation (ICSC) of the TWGHs was set up in eight different districts of Hong Kong to provide a free smoking cessation service to Hong Kong citizens. An integrated model of counselling and pharmacotherapy was adopted. It has been providing both pharmacotherapy and counselling services for smokers free of charge. Since then, ICSC is one of the major prescribers of varenicline in Hong Kong. This study is the first local research on the use of varenicline in Hong Kong. It aims to evaluate the efficacy and adverse event profiles of varenicline and the attitude and barriers on its use by general practitioners in private practice. Private general practitioners are the major health care providers to the public, and yet there is financial implication on the clients if expensive drugs are being used. Being one of the main prescribers of varenicline, ICSC is chosen to study the efficacy of this drug. The retrospective cohort study and the questionnaire survey are integrated together because the usage of a drug depends on its efficacy, cost, and the knowledge and attitudes of the prescribing doctor. Methods: research setting, design, and data collectionThis is a retrospective observational study together with a questionnaire survey. Target participants of the efficacy study were smokers attending TWGHs ICSC services in different districts of Hong Kong. All cases who started treatment during the period of 1/1/2015 to 31/12/2016 were reviewed. The inclusion criteria of the study were smokers aged 18 years or above and had neither current nor past history of neuropsychiatric diseases. There was no contraindication to the use of varenicline. All participants seeking help to quit smoking in ICSC would be screened for neuropsychiatric diseases and contraindication to the use of varenicline. After full explanation of treatment options, those who opted for varenicline were included in the study. A standard dose (1 mg twice daily with an initial titration week) of varenicline for twelve weeks was prescribed. In addition, they would also receive counselling provided by registered social workers who had been trained in smoking cessation with motivational interview technique and cognitive behavioural therapy. Participants would be followed up at one to two weeks intervals until treatment ended at 12th weeks. During the first intake, basic demographics would be collected. Bedfort smokerlyser would be used to check carbon monoxide level at each follow up visit to ascertain abstinence. Main outcome measures were a self-report 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 26th week by phone enquiries. Intention to treat analysis was adopted and those who defaulted follow up or had lost contact would be considered as failure to quit. By individual case record review, the adverse events of varenicline as reported by the smokers and the discontinuation rate due to side effects were recorded for subsequent analysis. At the same time, a survey questionnaire was posted to general practitioners in private practice registered with the primary care registry of Hong Kong in May 2016 to invite them to join the study. This list might not be comprehensive because doctors registered on a voluntary basis. Doctors in specialty practices were excluded. Doctors working in the public sector and TWGH ICSC were also excluded because varenicline is an expensive drug and it is supplied free of charge by ICSC, and with a nominal fee in general outpatient clinics in public sector. The survey captured data on their use of varenicline, their attitude and practices on smoking cessation counselling in a user paid system. In order to get a good response rate, a HK$50 coffee shop coupon would be awarded to 50 respondents after a lucky draw. Statistically analysisDescriptive statistics was used for analysis using frequency and percentage since all the data were categorised. Analytical statistics were not used because this was a qualitative research. ResultParticipants were mostly self-referred (99%) and a few (1%) were referred by other health care workers. None of them had used varenicline before. A total of 560 subjects were included in the study. Table 1 showed that there were 459 (82%) male and 101 (18%) female. The mean age was 41.9 years old (SD=10.9) and average cigarette consumption per day was 23.0 (SD=10.0). Mean Fagerstrom score was 6.0 (SD=2.3). 39.6% regularly used alcohol at least once a month. The 7-day point prevalence quit rate at 26th week was 43.2 (252/560) %. There was no serious adverse event (AE) which was defined by the investigators as any untoward medical occurrence that resulted in death, or life threatening (immediate risk of death) or required inpatient hospitalisation. The side effect profile is listed in Table 2. Participants might report more than one adverse event. The total incidence of any AE was 290 (51.8%) and 21 (3.7%) subjects needed early termination of treatment either at patient’s request or by doctor. Gastrointestinal disturbances were most commonly reported. 21.4% of the subjects had dyspepsia and 6.4% had nausea. 0.89% subjects asked for termination of drug because of severe dyspepsia; 1% subjects needed early termination because of intolerable nausea or vomiting. Other less common gastro-intestinal disturbances included diarrhoea (1.6%), abdominal pain (0.35%), reflux (12.5%) and constipation (0.35%). Neuropsychiatric AE included drowsiness (5.71%), dizziness (2.85%), headache (2.85%), psychomotor retardation (0.35%) and impaired concentration (0.17%). Sleep disturbance was not uncommon (6.78%). 1.06% r epor t ed low mood and 2 subj e c t s had sui c ida l ideation. 1.96% became more irritable and 1 subject had involved in a fight with people. There were no serious AE or fatalities.

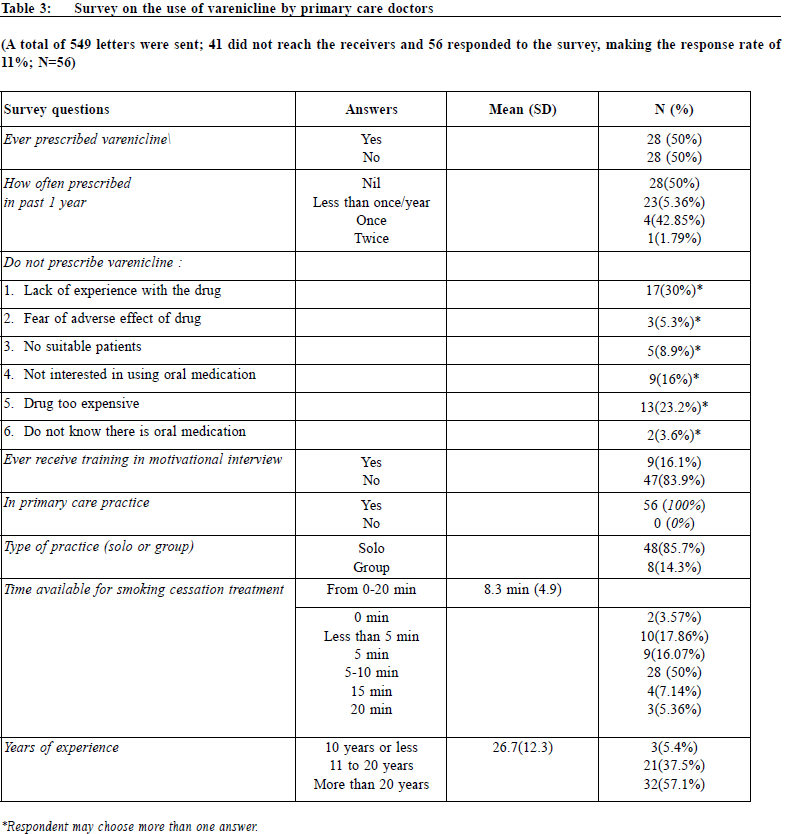

As to survey on the use of varenicline, a total of 549 letters were sent. 41 were not able to reach the receivers and 56 responded to the survey, making the response rate of 11%. The survey result was tabulated in Table 2. 50% of doctors had never used the drug before. The reasons for not using the drug were mainly lack of experience with the drug (30%) and the drug was too expensive (23%). 83.9% had not received training on motivational interview and 3.6% did not know there is oral medication for smoking cessation. The average time for smoking cessation counselling affordable by doctors was 8.3 minutes (SD=4.9).

DiscussionThis is the first local study on the use of varenicline including its efficacy and safety. It is an observational study which is designed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of a treatment in a real-world clinical setting. Observational studies can be considered as useful and complementary to Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs).12 Efficacy and effectivenessSeveral cohort studies have been conducted which compared varenicline with Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT), and the majority reported a higher effectiveness of varenicline.12,13,14,15 The pooled RR for continuous or sustained abstinence at six months for varenicline at standard dosage versus placebo was 2.24 The risk ratios (RR) for varenicline versus NRT for abstinence at six months was 1.25.16 Overseas Randomised Clinical Trials (RCT) studies and observational studies on the effectiveness of varenicline reported that the 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 3 months varied from 38% to 67% and at 6 months from 33.5% to 57% respectively.6,17,18,19,20 In our study, the 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate was 43.2% at 26th week. This is comparable to some overseas studies, but is higher than that of an observational study in Beijing, China. Their 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate at 6 months was 37.1%.19 Their demographics were comparable to ours. The reason for the difference is not apparent. This might be due to the fact that our counsellors were social workers who gave intensive counselling with motivational techniques and cognitive behavioural therapy, whereas their attending physicians gave the counselling and the duration of the counselling was not mentioned. Safety of vareniclineVarenicline was reported to be well tolerated, with nausea being the most commonly reported adverse event during clinical trials. Adverse events (AEs) were reported to be generally mild to moderate in severity. In an inter-European observational study, reported AEs included nausea (8.9%), sleep disturbances (5.1%), abnormal dreams (1.8%), depressed mood (0.4%) and impulsive behaviour (0.2%).21 Another inter-Asian observational study reported AE as nausea (11.1%), dizziness (2.9%), insomnia (2.3%), abnormal dreams (2.0%) and depression (0.3%).20 Our study reported AE with nausea (6.4%), sleep disturbances inc luding abnorma l dr e ams (6.78%) , low mood (1.07%), irritability (1.96%) and dizziness (2.85%). No cardiovascular adverse event was found in these three studies. Our study had higher incidence of gastrointestinal AE because we included dyspepsia as an AE. On the other hand, one single centre observational study by Jiang B et al. in China19 reported that the most frequent AE were gastro-intestinal disorders (12.7%), sleep disorders (2.7%), dizziness (3.3%) and cardiovascular system disorders (2.4%: palpitation). There was no report of depressed mood. As to psychiatric AE, Gunnell et al. found no evidence that varenicline was associated with an increased risk of depression (hazard ratio 0.88 [0.77 to 1.00] or suicidal thoughts 1.43 [0.53 to 3.85]), although the limited study power meant they could not rule out either a halving or a twofold increase in risk.22 A randomised double blind placebo controlled trial also commented that there was no significant increase in overall psychiatric disorders other than sleep disorders and disturbances in vareniclinetreated subjects who had no pre-existing psychiatric disorder.23 Another meta-analysis found no evidence of an increased risk of suicide or attempted suicide, suicidal ideation, depression, or death with varenicline.9 In fact, in 2016 the FDA removed the Boxed Warning statements regarding the risk of serious neuropsychiatric events from the varenicline label as a result of the "Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES)" study published in Lancet.24 Although various neuropsychiatric symptoms such as irritability, aggression, depression and suicide had been reported to occur in patients taking varenicline since it was launched25,26,27, some of the neuropsychiatric symptoms might be due to nicotine withdrawal.28 In our cohort, 6 subjects (1.07%) had low mood and 2 subjects (0.3%) had suicidal ideation. However direct causal relationship could not be ascertained and there was no placebo control group for comparison. Depressed mood, rarely suicidal ideation, may be a symptom of nicotine withdrawal. It is important to monitor the mood of patients taking varenicline even without medical history of depression. There was no report of abnormal behaviour despite 39.6% of our subjects had regular use of alcohol. It might be due to the fact that we cautioned the use of alcohol and to avoid alcohol three hours before using varenicline. We also reported AE not mentioned in other studies such as psychomotor retardation, tinnitus, muscle ache, loss of taste and nocturia. Again direct causal relationship could not be confirmed. Survey on varenicline useIt was noted that prescription of varenicline increased rapidly after it became available on National Health Service (NHS) in United Kingdom (UK).29 In Hong Kong, we have the impression that the usage of varenicline is low in private practice and therefore would like to know more about its use. From this survey, 50% had never used the drug and 3.6% did not know there was oral medication for smoking cessation even though most of these doctors (96%) had more than 10 years’ experiences of clinical practice. 16% showed no interest in smoking cessation. Counselling is an important element for smoking cessation; but only an average of 8.3 minutes consultation time could be offered to smoking cessation in this survey. 23.2% commented that the drug was too expensive. Since smokers have to pay for the drug, the cost of the twelve-week medication can be deterring. Oversea and local studies revealed that obstacles in providing smoking cessation counselling included lack of patient motivation, lack of doctor's time in consultation, lack of expertise in smoking cessation, doubts on efficacy of available therapies on smoking-cessation, and fear of damaging doctor-patient relationship.30,31 In our study, we had no intention to verify all these points.

Another systemic review on the attitude and beliefs of family physicians towards discussing smoking cessation with patients also demonstrated that the most common negative belief or attitude was that discussing smoking wa s too t ime - consuming. They l a cked confidence to engage in such discussions.32 In order to help smokers to quit, medical education on smoking cessation may be conducted. Another option is Private and Public / Non - Governmental Organisation (NGO) collaboration. Doctors may refer cases to clinics specialised in smoking cessation where free medications, counselling and behavioural support will be provided. In fact smoking cessation guidelines in UK recommended that specialist smokers’ clinics should be the first point of referral for smokers wanting help beyond what can be provided through brief advice from the General Practitioner (GP).33 The strengths of our study are relatively large sample size and a longer follow-up period of 6 months. The major limitation of the survey study on use of varenicline is the low response rate and the survey is restricted to private doctor registered with the primary care registry, which is a voluntary registration. Doctors not in the registry are not included. We have already tried to boost up the response rate by offering incentive and cutting short the questionnaire. In our survey, we have not asked their training needs or any necessary service support and their use of other smoking cessation drugs. In view of the small sample size, we do not attempt to do any statistical analysis on years of experience, district of practice or type of practice (solo or group). As to our study on efficacy and safety on varenicline, there was no controlled group for comparison or a head to head comparison with other medications for smoking cessation and the compliance with medication for those who had completed the treatment was not evaluated. ConclusionVarenicline is an effective drug for smoking cessation and is generally safe to use in patients without neuropsychiatric disease. However, it may be necessary to monitor the mood of the patient when being used. It is noted that there are some barriers for private practitioners to provide smoking cessation service. More medical education may be provided and referral to specialist smokers’ clinic may be considered if deemed necessary to help smokers to receive a free and comprehensive smoking cessation service. Acknowledgement:We thank Dr Mak Kin Mei for retrieving some of case files and all counsellors and nurses working in TWGHs ICSC for their counselling work.

Kin-sang Ho MBBS, FHKAM (Medicine), FHKAM (Family Medicine) Correspondence to: Kin-sang Ho, 17/F Tung Sun Commercial Centre, 194-200

Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: kinsang.ho@tungwah.org.hk

References:

|

|