|

March 2018, Volume 40, No. 1

|

Update Article

|

Diagnosis and Management of Breast MassSharon WW Chan 陳穎懷, Yuh-meei Cheng 鄭裕美, Siu-king Law 羅小琼, Po-ching Ng 吳溥澄 HK Pract 2018;40:12-24 Summary

摘要

IntroductionBreast mass is the most common symptom seen in specialist breast clinics. The discovery of a breast mass often leads to a high level of anxiety for the patient. While accurate diagnosis to exclude breast cancer is important, education in avoiding over treatment of benign breast conditions are equally significant. Common causes of breast massMajority of breast masses are benign, but a mass is also the commonest presenting symptom of breast cancer. Causes of breast mass differ amongst different age groups. Benign breast diseases are more common in the younger aged women. Breast cancer risks generally increases with age. The median age of breast cancer in Hong Kong is 56 years old (20-85+). In 2015, 3900 cases of breast cancer were registered and is still among the commonest cancers in women in Hong Kong. Lifetime breast cancer risk (for female age before 75) is 1 in every 16.1 The breast is a dynamic structure that undergoes cyclical changes during the menstrual cycle and throughout a woman’s reproductive life. “Aberration of Normal Development and Involution” (ANDI), was first published in Lancet in 1987. As its name implies, most benign breast disorders is a spectrum that ranges from normal to aberration and occasionally to disease in relation to different periods throughout the reproductive life (Table 1). Other conditions like phyllodes tumour, haematoma, lipoma, fat necrosis etc.., are other causes of benign breast masses across different age group of patients. Triple AssessmentAll palpable breast masses require evaluation via the triple assessment approach. This includes: 1) clinical, 2) radiological or imaging (mammography and/or ultrasound) and 3) pathological assessment (core biopsy or fine needle aspiration cytology). If all investigations concur, diagnosis was made in 96% of patients.2 Clinical assessmentDetailed history with questions specifically regarding the mass should include the onset, the duration and whether the mass has changed in size in relation to the menstrual cycle. Other breast-oriented history including presence of nipple discharge, skin changes or axillary lymph node should be evaluated. Significant clues suggestive of malignancy include new onset of breast lump in a postmenopausal lady, asymmetrical ill-defined nodularity particularly if this does not vary with menstrual cycles, single duct bloody nipple discharge, recent history of nipple retraction or distortion and new skin changes such as skin nodule, retraction, dimpling or ulceration. Breast symptoms which raise the suspicion of breast cancer should be investigated to exclude malignancy. Reviewing individual risk factors is important as risks of developing breast cancer is higher in women with those significant risk factors as listed in Table 2. However, the absence of any does not exclude the possibility of breast cancer.3 Full physical examination of both breasts and axillae and the supraclavicular fossae lymph nodes, including inspection and palpation, should be performed. Patient should be asked to point to the concerned area if the mass is not obvious on examination allowing physicians to examine the concerned area in detail so as to avoid missing any breast masses. Arms should be elevated to identify any “hidden” breast mass (Figure 1). The normal breast should be examined first to assess the normal consistency of the breast. Using the finger pads of the middle three fingers to palpable the breast in a systematic manner is more sensitive in detection of breast masses. The retro – areola region should also be examined. Patient should be invited to demonstrate any nipple discharge.

Patient should be asked to point to the concerned area if the mass is not obvious on examination allowing physicians to examine the concerned area in detail so as to avoid missing any breast masses. Arms should be elevated to identify any “hidden” breast mass (Figure 1). The normal breast should be examined first to assess the normal consistency of the breast. Using the finger pads of the middle three fingers to palpable the breast in a systematic manner is more sensitive in detection of breast masses. The retro – areola region should also be examined. Patient should be invited to demonstrate any nipple discharge. In general, benign masses are usually mobile with well-defined margins; and are soft to firm in consistency and have smooth overlying skin. Malignant masses are usually hard, immobile, with poorly defined borders, and might be fixed to the overlying skin and underlying muscle. Clinical signs of skin dimpling, nipple retraction and peau d’ orange should alert the physician to the possibility of an underlying breast cancer. However, some breast cancers (<10%) present as asymmetrical nodularity rather that a discrete mass and these patients pose diagnostic challenges to physicians. It is important to differentiate whether the nodularity is an asymmetrical focus or is part of a generalised nodularity. Generalised nodularity, usually bilateral and symmetrical tends to fluctuate with the menstrual cycle. This may indicate benign fibrocystic changes. In contrast, if asymmetrical thickening persists after the menstrual cycle, it must then be fully investigated to exclude a possible underlying malignancy. Inflammatory breast cancer can mimic simple breast infection. If inflammation, or an associated mass lesion, persists after the completion of a course of antibiotics, further investigation is required to exclude possible underlying malignancy (Figure 2). Risk score triage systemIn our centre, for patients who have been referred to our Specialist Breast Clinic, we use our own developed and validated risk score system to triage them according to the referral letter and a questionnaire.4 One cohort of 493 patients were used to develop the risk score. Another cohort of 494 patients from same hospital was used to validate the system. The derivation cohort shows that the predictors for breast cancer are age >40 (OR 18), presence of breast lump (OR 26), bloody nipple discharge (OR 20), nipple abnormality (OR 6) and presence of skin changes (OR 22). In the validation cohort, the positive predictive value ranged from 0.2% with score 0-1, 21% with score 1.5-2.5 and 100% for score 3-4.5.4 (Graph 1). The performance (ROC curve) of this risk score system is excellent (AUC 0.88). It helps in the allocation of urgent appointments, and thus minimises delay in management and potentially improves survival of breast cancer patients.

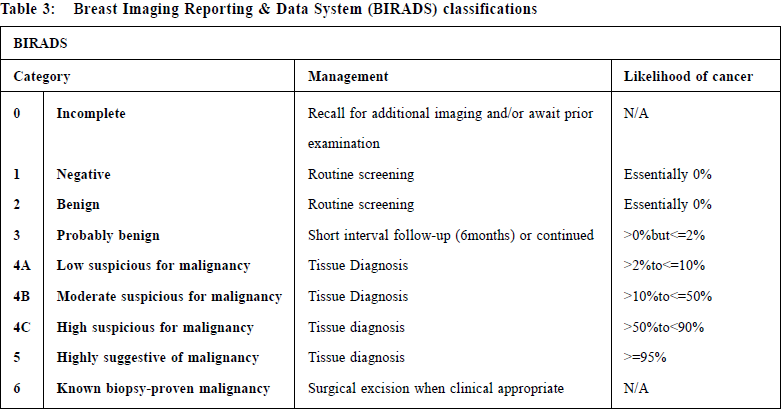

Imaging assessment Two-view mammography plus or ultrasound form are commonly used in Triple Assessment. Mammography is used for both screening and diagnostic purposes. All women over the age of 35 years old should have a mammogram as part of their triple assessment. However, mammogram is not routinely performed in women under 35 years old in some units as young women have denser breasts reducing the sensitivity of detecting any lesions. The two standard views of mammography are cranio-caudal (CC) and medial-lateral oblique (MLO). Additional views such as magnified view may be required for better characterisation of microcalcification, and compression view to clarify any suspicious mass or architecture distortion. The overall sensitivity of diagnostic mammography was 86-91%.5 The sensitivity of mammography for detecting breast cancer varies with ages and breast density. The sensitivity drops to 61% in women age 30-39.5 The most common findings suggestive of cancer are irregular or spiculated masses and clustered microcalcifications. The commonly used reporting system for mammography is the Breast Imaging Reporting & Data System (BIRADS), which is recommended by the American College of Radiology (Table 3).

Digital Breast tomosynthesis (DBT); often referred to as “3D” Mammography, creates image “slides” through the breast and thus reducing the overlap of normal dense breast tissue. DBT has shown to be an advantage over digital mammography with a higher cancer detection rates and fewer patient recalls for additional testing. American College of Radiology also stated that tomosynthesis has been shown to improve key screening parameters compared to digital mammography. With the use of the latest DBT plus synthesised 2D mammography, the radiation dose is similar to the standard 2D digital mammography. Ultrasound is particularly useful in the assessment of discrete breast lumps. It can distinguish between solid and cystic lesions (Figure 3). This allows fine needle aspiration of symptomatic breast cysts or core biopsy of solid lesions. The sensitivity of ultrasound ranges from 81.7% to 96%. In a local published study, the reported sensitivity of ultrasound was 97% and specificity was 97%.6 The sensitivity of USG is higher than MMG for palpable breast masses.7 The features that favor malignancy include: irregular shape, illdefined margin, solid hypoechogenicity, posterior acoustic shadowing, and tissue distortion. Ultrasound is also being routinely used to assess the axillae in women with breast cancer.8 Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of abnormal axillary lymph nodes can be done accurately. Up to 50% of patients with axillary metastasis disease can be diagnosed using this method, thus avoiding the need for sentinel node biopsy. The commonly used reporting system for ultrasound is also the Breast Imaging Reporting & Data System (BIRADS), which is recommended by the American College of Radiology is the same as for mammography. Breast elastography is a new sonographic imaging technique that provides information on breast lesions in addition to USG and MMG. The goal of elastography is to provide information about the stiffness (or elasticity) of tissues. USG elastographic techniques rely on the compression of tissues (Strain technique) or on the generation of shear-wave technique. It has been added to the BIRADS classification since 2013. However, the limitation of this technique is that there is an overlapping in firmness between benign and malignant lesions. Biopsy cannot be avoided by using elastography in most cases. MRI is the most sensitive technique for detection of breast cancer, approaching 100% for invasive cancer and up to 92% for ductal carcinoma in situ, but it has high false positive rates. The current indications for MRI in diagnostic imaging according to the American Society of Breast Surgeons Consensus Statement are:

The use of Breast Thermography (Digital Infrared detecting metabolic activity and vascular circulation) of breast and Electrical Impedance Tomography (measures conductivity values) is still investigational.9 Pathology assessmentPathology assessment includes: fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) or core biopsy. The sensitivity, specificity, false negative rate, false positive rate and accuracy of core needle biopsy compared with fine needle aspiration are showed in the following table 4.10 The advantage of FNAC is being less invasive, and it can provide a therapeutic aspiration. However, core biopsy is recommended if the palpable mass is suspicious of breast cancer. Though core biopsy is more invasive, it is more accurate with a high sensitivity and specificity. It can distinguish invasive carcinoma from in-situ carcinoma. It is also reliable in providing information on the tumour type, tumour grading and immunochemistry for receptor status. Multidisciplinary meetingConcordant triple assessment establishes the diagnosis of breast mass. Management of disconcordant lesions shall be discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting involving breast surgeons, radiologists and pathologists. Any suspicious lesion requires further assessment by vacuum assisted core needle biopsy (VACNB) or excisional biopsy. Open excisional biopsy should be minimal, and the alternative Radiofrequency INTACT biopsy can be considered (Chart 1). Treatment of breast massMost benign breast lumps do not need to be treated unless they are symptomatic, that is, has become particularly large; painful or are growing in size. CystsSimple cysts contribute to about 25% of all palpable breast masses.11 More than half of these lesions spontaneously regressed in 1 year.12 Simple cysts confirmed on ultrasonography need no further follow up if patients have no related symptoms (BIRADS 2). Needle aspiration is sometimes performed for symptomatic relief. Ultrasound guided aspiration to complete resolution can be performed with an 18- to 20- gauge fine needle.

Complicated cysts are cysts with internal debris. As an isolated finding on imaging, homogenous complicated cysts are probably benign and classified as BIRADS 3. This should be distinguished from complex cystic lesions, which are masses with solid components such as thick wall (>=0.5mm), thick septations (>= 0.5mm), intracystic masses or solid mass with cystic areas. They are classified as BIRADS 4 and merit biopsy.11 FibroadenomaFibroadenoma (FA) is a common benign breast disorder, contributing to the majority of palpable breast masses in young age patients. They are sometimes called breast mice, or breast mouse if single, owing to their high mobility in the breast. They are usually solitary but can be multiple or bilateral in 10-15% of patients.13 About half of these lesions can disappear in around 5 years.14 However, FA can sometimes grow rapidly in adolescence (juvenile FA) or during pregnancy. Those FA larger than 5cm is called giant FA. Although they are entirely benign, early surgical removal is recommended as they can become large enough to deform the breast. Fibroadenomas carry little to no increased risk of breast cancer15 but incidental finding of a malignant lesion in FA can occur just as malignancy can in any other part of the breast. Once confirmed by triple assessment, FA can be observed and managed conservatively. Excision can be considered if the lesion is growing or becomes symptomatic. Excisional biopsy is also offered when triple assessment results are not concordant. An alternative to open excision, be it under local or general anaesthesia, is via percutaneous minimally invasive methods, of such, will be discussed later.

Phyllodes tumours Phyllodes are an uncommon group of breast fibroepithelial tumours. They represent 2-3% of all fibroepithelial lesions and less than 1% of all palpable breast tumours.16 The WHO classified such tumours as benign, borderline or malignant based on their stromal cellularity and atypia, stromal overgrowth, mitotic activity and pathological margins.17 According to a recent pathological consensus review published in 2016, benign phyllodes and cellular fibroadenoma are regarded as a continuous spectrum of disease.18 Thus, biopsies are necessary but may be difficult to distinguish between the two. Surgical excision is the mainstay of management. The NCCN guidelines suggest a wide negative margin of 1cm to ensure completeness of excision and to reduce recurrence especially for borderline and malignant phyllodes. Twenty percent of tumours can grow to over 10cm in size. Such giant phyllodes may sometimes render the patient having to undergo a mastectomy.19 For malignant phylloides, risks of lymph node metastasis are uncommon, < 1%.19 Therefore, routine axillary dissection is not recommended.16,19 Roles of adjuvant radiation, chemotherapy and anti-estrogen therapies remains uncertain. An analysis of 3120 malignant phyllodes from the US National Cancer Data Base20 shows that adjuvant radiation is associated with a reduced local recurrence but has no impact on disease free or overall survival. There are no randomised clinical trials assessing the role of adjuvant chemotherapy or anti-estrogen therapy. PapillomasPapillomas are discrete tumours of the epithelium of mammary ducts. Central papillomas tends to be solitary and the peripheral ones arising from terminal ductal-lobular units are usually multiple.21 It commonly presents as nipple discharge or image detected abnormality. Sometimes it grows to a palpable mass located in the peri–areolar region. Management of papillary lesions diagnosed via core needle biopsy remains controversial, as both quantitative and qualitative pathological assessment are needed to ascertain their benign nature and to rule out the possibility of ‘upgrade’ to malignancy. Incidence of these ‘upgrade’ is reported to be about 14%-21% in literature but can be as high as 68%.22,23 According to a Meta-analysis in 2013 that includes over 2000 non– malignant papillary lesions, presence of atypia and positive mammographic findings contribute significantly to the under-estimation of papillary lesions.24 Most institutions recommend excision of papillomas diagnosed via core needle biopsy. Some institutions advocate observation but require careful clinical, radiological and pathological correlations. High–risk lesions (lesions with atypia, lesions size > 1cm or lesions in patients older than 50 years old) warrants excision. Minimal invasive techniques can be applied to avoid open excision if sonograhpic complete excision can be achieved and if there is no atypia on histology. Minimally invasive surgeryMinimally invasive surgeries (MIS) are gaining a lot of popularity these days as they advocate smaller or even no scars, a faster recovery time, much better cosmesis and a higher patient satisfaction post operatively. Such methods have an additional benefit of lower costs and can be done under local anesthesia. For their use in breast lumps, MIS are mainly divided into two common types. One type is that MIS ablates the lesions (not excise), such as the use of high frequency ultrasound (HIFU), cryoablation, laser photocoagulation. The other type is by the use of percutaneous excision methods such as vacuum assisted needle excisional biopsy (VACNB) or radiofrequency biopsy (Intact) which aims to remove breast lesions as a whole with margins. Cryoablation has been FDA approved to manage fibroadenoma since 2001 and endorsed by the American Society of Breast Surgeons as a successful alternative to treating FA. These non-excisional ablative means have a main drawback that no definitive pathology can be provided as there will not be a specimen. Stereotactic or ultrasound-guided VACNB (Figure 4) can be used for either diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Compared to Core Needle Biopsy (CNB), VACNB allows sufficient specimen through a single incision (4-5mm) under local anaesthesia, while it eliminates sampling error, decreases likelihood of histological underestimation, decreases imaginghistological discordance and decreases re-biopsy rates. The efficacy of VACNB in completely removing a lesion can be as high as 97%25; it is increasingly being used as a therapeutic means for benign breast lesions. Our centre’s initial experience of 93 cytologically or histologically confirmed benign breast mass (1-3cm), sonographic complete excision rate is up to 97%. Ten patients with histological upgrades include phyllodes tumour, papilloma, atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in- situ. They were all offered open excision.26 (Figure 5). Stereotactic or ultrasound-guided INTACT excision system (Figure 6) is a biopsy device with a radiofrequency ablation “basket”. Contrary to VACNB in removing a lesion in a piecemeal fashion, INTACT allows en bloc removal of a lesion with an “intact” specimen for histological margin assessment. It is performed through a single incision (8 mm) under local anaesthesia. It further decreases histological underestimation, and has been used for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in BIRADS 4 or 5 or other high–risk lesions. Our centre’s initial experience of 52 breast lesions (BIRADS 4 or Cytological atypia, size 0.29-1.58cm), intra–operative complete excision was achieved for all these patients. For benign papillomas that require margin assessment, we achieved a 94% margin clearance rate. (Figure 7) Two patients were diagnosed to have breast cancer and both received subsequent cancer surgery.27 Breast cancerAccording to the Hong Kong Cancer Registry, breast cancer has been the most common cancer in women in Hong Kong.1 Modern breast cancer management emphasise a multidisciplinary approach and personalised therapy. Management of individual breast cancer cases are discussed in multidisciplinary meetings. For early operable breast cancers, surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Randomised control trials have shown that radical mastectomy offers no survival advantage over modified radical mastectomy where chest wall muscles and level III axilla lymph nodes are preserved. Breast conservative surgery (BCS) plus irradiation has also been proven to offer equal benefits in overall survival compare to mastectomy.28, 29 The American Society of Breast Surgeons practice guidelines in 2015 states that the current indication for BCS are “A biopsy-proven diagnosis of DCIS or invasive breast cancer clinically assessed as resectable with clear margins and with an acceptable cosmetic result”. The absolute contraindications include early pregnancy, multicentric tumours involving 2 or more quadrants of the breast, diffuse malignant microcalcifications, inflammatory breast cancer and persistent positive pathological margins.30 Large tumors that render local excision impossible with negative margins and satisfactory cosmetic outcomes were once not feasible. Nowadays, as shown with the results from the National Cancer Database in the United States, the indication of BCS can be extended by means of neoadjuvant therapy.31 Oncoplastic breast surgery also allows a wider excision without causing breast deformity and thus further extends the indication of BCS for larger tumours.32 The concept of such has evolved to include reconstructions after partial (BCS) or total mastectomies (conservative mastectomy).33 Oncoplastic BCS includes surgical techniques to displace or replace lost volumes after wide excision of tumours in BCS patients. These techniques are shown to be able to achieve excellent outcomes in Asian women with a smaller breast size (Figure 8).34 Reconstruction after conservative mastectomies (skin sparing or nipple sparing mastectomy) include implant or autologous flap reconstructions (Figure 9), can be done immediately with breast cancer surgery, or delayed after adjuvant treatment. Axilla staging is of paramount importance in breast cancer management. Sentinel lymph node (SLN) excision is now considered the standard for clinical node negative patients (Figure 10).35 It has the advantage of significantly reducing the risks of lymphodema and ipsilateral arm morbidities whilst having equal survival results when compared to node negative patients who have had axillary dissection. Recent phase 3 multicenter non–inferiority trial also shows that it is safe not to perform complete axillary dissection for T1-T2 early breast cancers when there are less than 2 metastatic SLN in those who have undergone breast conservation therapy.36 In the neoadjuvant setting, SLN is possible with careful patient selection and a well–designed management algorithm.37,38,39

Adjuvant therapy is an important component in breast cancer management as it significantly decreases the recurrence rate and improves overall survival. This includes radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, chemotherapy and different targeted therapies. Treatment protocol is based on updated guidelines like St Gallen consensus treatment guidelines.40 Genomic assay can be used to help identify those women with early stage estrogen receptor positive breast cancer who are more likely to benefit from adding chemotherapy to their hormonal treatment. ConclusionManagement of breast mass requires a careful triple assessment approach. Choices of investigation differ depending on the availability of expertise and facilities. Multidisciplinary meetings involving radiologist, pathologist, surgeon and oncologist is the key to success for the diagnosis and management of benign or malignant breast mass. Open surgery shall be limited to high–risk lesions or breast cancer patients. Minimal invasive surgery and oncoplastic breast surgery are advances that minimise surgical morbidity and optimise cosmetic outcome.

Sharon WW Chan,MBBS (HK), FRACS, FCSHK, FHKAM (Surgery) Correspondence to:Dr Sharon WW Chan, Consultant, Department of Surgery, United

Christian Hospital,130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Hong Kong

SAR.

E-mail: chanww1@ha.org.hk

References:

|

|