|

September 2018, Volume 40, No. 3

|

Original Article

|

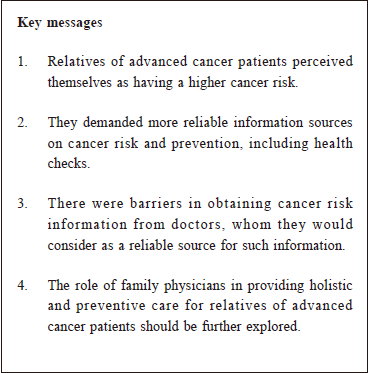

Cancer risk perception and prevention expectation behaviour of relatives of advanced cancer patients – a qualitative studyLai-mo Yau 邱禮武,Yuk-tsan Wun 溫煜讚,Tai-pong Lam 林大邦,Tseng-kwong Wong 黃增光,Po-tin LAM 林寶鈿, David VK Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2018;40:75-81 SummaryObjectives: Design: Qualitative study - structured focus group interviews with relatives of advanced cancer patients. Subjects: 19 relatives of advanced cancer patients. Main outcome measures: Views on cancer risk and health seeking behaviour.

Results: Relat i ves of advanced cancer pat ient s perceived themselves as having a higher cancer risk. They were henceforth more health conscious and wished to have health checks for cancer prevention. They also wished to seek more information on cancer risk, especially from health care professionals. However there were barriers in getting such information from doctors. Conclusion: Relatives of advanced cancer patients need more reliable information on cancer risk and prevention. Family physicians, with emphasis on holistic and preventive care, are capable of meeting such needs. Further study is needed to explore the view of family physicians. Keywords: Cancer risk perception, prevention behaviour, relatives of advanced cancer patients, family physicians 摘要目的: 設計: 定性研究–對晚期癌症患者親屬作結構性焦點小組 訪談。 對象:19位晚期癌症患者的親屬。 主要測量內容:對患癌症風險的看法和其就醫的行為。 結果:晚期癌症患者的親屬認為自己有較高的癌症風險。 他們比前更注重健康,並希望能有健康檢查以防止患上晚 期癌症。他們希望獲取更多關於癌症風險的資訊,尤其從 醫護人員中的資訊,但常遇障礙。 結論:晚期癌症患者親屬對患癌症的風險和預防需要更可 靠的信息。由於家庭醫生特別著重全人醫療和預防保健, 故能照顧這些親屬和迎合他們的需求。建議進一步研究家 庭醫生對此的意見。 關鍵字:癌症風險感知,預防行為,晚期癌症患者的親 屬,家庭醫生 IntroductionMalignant neoplasms are the main cause of deaths in Hong Kong, accounting for around 30% of all deaths in 2015.1 Most patients with advanced cancers are treated and followed-up by the oncology or palliative care units of hospitals. As outpatients, they are usually cared for in the community by their families. While there are various supports and funding for the care of cancer patients, the needs of their relatives, especially the care-givers, are often overlooked. Apart from the stress of caring for the sick, these relatives may perceive themselves as having an increased cancer risk because of having such family history.2,3 Their needs of health care, both physical and psychological, are not addressed by the hospital specialists because they have not developed any disease yet. In the case of breast cancer, a study showed that the sisters of patients newly diagnosed with breast cancer were under heavy cancer-related distress and perceived themselves as having a higher personal risk of breast cancer.4 The perceived breast cancer risk influenced the adherence to mammography screening guidelines5, supporting that perceived risk was pivotal in the precautionary health behaviour. On the other hand, information, support, and communication were found to be the most important factors in facilitating the women with a family history of breast cancer to cope with their concern of increased cancer risk.6 As family physicians, we also have the privilege of caring for the needs of the patient’s family members7, as well as caring for the cancer patient. If we understand the risk perception, worries and subsequent health seeking behaviour of the cancer patient’s relatives, we could offer them more comprehensive and cost effective counselling and advice. However, in Hong Kong, these areas are largely unexplored. The objective of this study was to assess the perceptions of cancer risk, preventive behaviour and the corresponding needs among relatives of advanced cancer patients. MethodsWe adopted a qualitative approach for this study because of the following reasons. Firstly, there was no local data on this topic and hence systematic comparisons and generalisation were not feasible. Secondly, the relatives’ perception, feelings, and expectations could be better expressed if they were encouraged and facilitated to talk freely. Thirdly, information from such a qualitative approach could be used to design questionnaires or generate hypotheses for further studies. Participants were recruited from the palliative care out-patient clinic of a regional hospital for focus-group interviews. They were approached by the principal investigator when they accompanied their relatives for medical appointments in the clinic. The recruited participants consisted of an evenly distribution of sexes and included the patients’ spouses, children, and siblings. They should be free from any past and present history of cancers. The participants were invited to take part on a voluntary basis and their opinions were recorded anonymously. All the focus-group discussions were facilitated by a moderator (the principal investigator). He was supported by an observer whose main role was to take notes of the participants’ non-verbal expression and interactions during the discussion, as well as helping with arrangements for the meeting place and refreshments. To ensure an in-depth discussion of the relevant issues, a set of open-ended questions was developed based on literature review and the investigators’ opinions. The discussion covered the worries after the cancer diagnosis of their relatives, perception of their own cancer risks, the source of general information concerning cancer and cancer risks, their practice on cancer prevention including health check and screenings. The focus-group discussions were conducted in Cantonese, audio-recorded with the consent of the participants and transcribed into Chinese (some quotations were further translated into English for publication purposes). The transcripts were then verified against the tapes by the focus-group observer. Two investigators independently read the transcripts, did the coding and extracted themes. Differences in coding were discussed and agreement was reached by consensus. Ethical considerationThe project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central / Kowloon East) of the Hospital Authority. ResultsThree focus-groups with five to seven participants each were conducted among first-degree relatives and spouses of advanced cancer patients under the care of the palliative unit of a regional hospital. The cancer patients’ information was not included in this study. Duration of the focus-groups ranged from 90 to 120 minutes. Nineteen relatives, aged 24-69 (mean 46) were recruited. Demographics of the relatives are shown in Table 1. As many of the cancer patients were elderly, they were more likely to be looked after by their middle-aged children and thus more of these relatives were recruited. All of the participants visited the patients regularly and some of them even lived with the patients.

1. Perceived higher cancer risk After the diagnosis of the patient’s cancer, most relatives worried about the treatment of the patient and the financial issues involved. Moreover, they also worried about their own cancer risk; whether they would get cancer too (not necessarily the same cancer as the patient’s). “I would certainly think about his treatment first, only then would I think of myself [getting cancer] just like him.” (Son of a lung cancer patient aged 57) “As we know our family have this susceptibility [to cancer], we [the family] have to be more alarmed, I mean alert.” (Daughter of a prostate cancer patient, aged 46) Concerning the risk factors, genetic linkage or inheritance was the most recognised among participants. “We are his children, would we inherit that too? Of course I’m worried.” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 55) Environmental factors were also recognised by the participants to be causes of cancer. “The high risk is due to our similar lifestyle, because… my dad likes smoking and drinking, sleeps late … and he has high stress at work. … In fact I have a similar lifestyle. … Therefore I’m worried, that I would have a higher chance of getting cancer that way too.” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 29) “Something would be inherited from the family, something would not, but lifestyle also plays a role.” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 41) 2. Information seekinga. Source Books or magazines, the internet, word-of-mouth, and health talks were the most common source of information about cancer risk. Few participants obtained their information directly from doctors. “I’d read the information online, to check the symptoms, what it is like before [the diagnosis of cancer]. I have a clear view of these.” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 21) “Since he had liver cancer, I’d read books about liver cancer.” (Sister of a liver cancer patient, aged 60) “…[from] the press, newspapers, internet, but I had never learnt about this kind of risks from a doctor” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 32) b. Quality of the informationParticipants raised concerns about the quality and validity of the information, and the source from the internet is voluminous. “In fact I feel that there is too much [information]. You will certainly find something [on the internet], but are they reliable?...I think unless I ask the doctor directly, there’s hardly any way to make all these clear and certain. Going online…I believe lots of information can be found, but I can’t be 100% sure if the answer given is correct.” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 29) “Lots of information and promotion nowadays, but none is from authority (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 55) Most participants agreed that information from doctors or healthcare professionals is more authentic. “if the doctor tells me in person, the credibility will be higher” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 29) “I’ll trust whatever any team of doctors or nurses explain to me, or ask me to pay attention to…” (Brother of a liver cancer patient, aged 37) c. Barriers to doctors being information sourceAlthough doctors were considered as a preferred source of information, participants highlighted that doctors’ attitude and tight schedules imposed barriers. This was more relevant to doctors in the public sector and doctors who were caring for their relatives with cancer. “You may ask, but the doctor may not answer, because he’s busy. … Those doctors said—this is the one [the cancer patient] who sees the doctor; you’re not, you’re just a relative.” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 48) “I think doctors are just like that, just like how they attended to my dad, focusing on my dad’s condition, and then wrote all the way till the end, as long as you sat there, and threw one or two words when he finished. You wouldn’t get the chance to ask” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 55) 3. Views on family doctorThe concept of family doctor was weak among the participants. Only a few had family doctors, but for those who had their family doctors, they had good experience from their family doctors concerning health check and overall health care. “Isn’t family doctor and private [doctor] the same thing?...Just like my dad, when there’s a cold or runny nose. They’re just outpatient service [providers]” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 48) “I always feel that family doctor is good. He’s more basic, and knows lots of things. All [my] kids were taken care of by him as they grew up. All in his hands, allergy or other things, he would know, so that [we] don’t need to search around.” (Daughter of a prostate cancer patient, aged 46) 4. General opinion on cancer preventionAll participants agreed that prevention was important in cancer. Some of them even urged the government to put more resources on prevention. “I think the health care [system] in Hong Kong only deals with you when there’s something wrong, but not when you’re fine.… There is just no prevention. … In fact I wonder why they do nothing for those with family history or hereditary diseases. … I think they can do better than that” (Brother of a liver cancer patient, aged 37) Most participants became more health conscious and adopted a better lifestyle after the diagnosis of their relative’s advanced cancer. They would seek advice or have medical consultation for minor symptoms earlier than before. “I will pay much more attention now. Before that I was unwilling to see the doctor when I was sick. I would just let myself recover, but now when I have stomach trouble like stomachache … I will go and see the doctor, or undergo blood test, eat more vegetables and less meat … like that. But in the past, I would just ignore it.” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 29) “My brothers…in fact after [dad was diagnosed to have cancer], they behaved better; bad habits like smoking and drinking … were seen less frequently now.” (Daughter of a prostate cancer patient, aged 46) 5. Specific opinion on health check to prevent cancera. Effectiveness Most participants agreed that health check might help to prevent cancer or diagnose cancer at an earlier stage. Some of them actually aimed to detect cancer via health check. On the other hand, they realised that health check did not have 100% sensitivity. Some of them thought that health check might be too general or superficial to detect cancer. “It may not be lung cancer, but at least you can check it out if your lungs have any problem. When you find a problem, you can find ways to tackle it. … I think it can.” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 21) “I think it is definitely useful, but it is just, I think, raising the percentage [of timely diagnosis] for a bit, not very much. … You may find the problem at the right time when you are lucky enough. Then you can have your treatment earlier, that’s it.” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 41) b. Barriers to health checkAlthough most participants considered health checks to be good for them, difficulty in choosing the right investigations and financial constraints were the major hurdles for health checks “It’s the money problem, too expensive, right? And haven’t got medical [insurance]” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 55) “I have seen those ‘whole body’ check-ups, or items in those checks, but even those who go frequently won’t check all the items. We have no idea what to check, and which plan to choose. Maybe there are lots of options. … But when I finished the ‘whole body’ check of plan A, I would miss some items in plan B. If that happened to be where I had got problems, then I would never know. We, the laypeople, don’t know which option suits us.” (Daughter of a lung cancer patient, aged 21) c. Service expectedWhen asked about the most wanted service specific for them, participants would like to have a healthcare professional, preferably a doctor, to review their medical history and provide appropriate advice on cancer prevention. Direct subsidisation for health check was also a popular service wanted by the participants. “After I told the doctor my family history, I wished the doctor to consider the situation to see if I have that disease or not. You know, ‘An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure’. … To be frank, the government’s not doing a good job on that.” (Brother of a liver cancer patient, aged 37) “I think there should be a team to follow up all the people [relatives],…, as some may have a higher risk, some lower. For those with higher risk, suggestions can be provided as what to do, or whether a follow-up plan should be launched.” (Son of a lung cancer patient, aged 41) “If there’re resources, it should be more pertinent like what you’ve said. There’d be a family doctor, who asks lots of questions, considers the risks you’d have … that means suggesting the kinds of checks you should make, or even performing the check for you, making an appointment with a few years’ interval. That would be the best.” (Son of a colon cancer patient, aged 40) DiscussionThe relatives of cancer patients in our focusgroups perceived a higher risk of cancer themselves and were more health conscious after the diagnosis of their relative’s cancer. They would like to have health checks as a preventive measure and to have more information about cancers especially from the medical profession. The fact that the relatives perceived a higher personal risk was observed in many international studies included in one systematic review.3 Like these studies, genetic linkage (family history) and lifestyle (e.g., cigarettes, alcohol) were conceived by our focusgroup participants as factors associated with perceived cancer-risk. But our participants also recognised that environmental factors played an important role. The perception of higher cancer-risk led to an increased need for information about their personal risk. A study in Canada on women who had a family history of breast cancer in their first degree relatives showed that information about personal risk of breast cancer was the most important information to them.8 Most of the relatives in our study sought information on cancer from books, magazines, the internet, words of mouth and health talks. Although they opined that information from doctors and health care professionals were the most reliable, only few of them sought information from doctors. An overseas study also showed that patients preferred to get information of cancer from doctors.9 Such a discrepancy between the desired and the actual information source may signify barriers in obtaining information from doctors or other health care workers. In our study, participants perceived that doctors’ attitudes and time constraint were the major barriers to information dispatch. A study conducted in Indonesia showed a sharp contrast between observed and ideal doctor-patient interaction and that time constraint was one of the factors, apart from a high patient load and preparedness of patients and doctors.10 Further research on family physicians’ view on the information needs of relatives of cancer patients is required to resolve the barriers. Our study also found that most relatives seldom sought health advice from doctors before they have symptoms. Their concept of the role of a family physician was weak. Most participants do not have a regular (or family) doctors and they only consult for episodic illness when problems arise. It may be due to the current segregated health care system and weak primary care foundation in Hong Kong. This phenomenon may contribute to the problem of time constraint for doctors to care for the information needs on cancer risk since doctors need to manage the patient’s physical complaints as their top priority during consultation, and much less time can be allocated to counselling of cancer risks. Patients in the private sector may not be willing to have another consultation for counselling only, while consultation quota in the public setting are very limited. With the emphasis on continuous, comprehensive and preventive care, family physicians are in a good position to provide counselling on cancer risks. The above study in Canada8 showed that family physicians were the most desired source of information and support about breast cancer risk, by over 95% of the participants. However, in Hong Kong, having a family doctor or regular doctor is considered a “luxury item” for the wealthy; people without a family doctor were mainly of lower socioeconomic status.11 This poses problem in providing an effective preventive care for most of the relatives of cancer patients in public hospitals.12 All participants in this study agreed that cancer prevention was important. Most of them were more health conscious and adopted a better lifestyle after the diagnosis of their relatives’ advanced cancer. They would seek advice or medical consultation for minor symptoms earlier than before. Some of them agreed that health check could be one of the ways to prevent cancer or to diagnose cancer at an earlier stage. However, the costs of the investigations and difficulty in choosing the right investigations were the major barriers for them. Many of the participants wished to have a healthcare professional, preferably doctor, to review their medical history and provide appropriate advice on prevention of cancer. There is a potential role for family physicians in Hong Kong to bridge the gap by providing accessible, comprehensive, and continuous primary care with emphasis on preventive care. Patient education on the effectiveness of health checks in cancer prevention and evidence based cancer prevention, including lifestyle changes, should be delivered by family physicians. A study in US showed that there is room for improvement for primary care physicians to care for patients with increased cancer risks.13 The readiness of Hong Kong primary care doctors to care for such patients can be further explored. LimitationA limitation of this qualitative study is that all the participants were patient relatives recruited from a regional hospital of Hospital Authority. A larger scale study involving relatives from other hospitals, including private hospitals, may provide a more comprehensive view.

ConclusionRelatives of advanced cancer patients do worry about cancer in themselves due to the family history. They hope to get more reliable information on cancer risks and preventive measures from health care professionals, especially doctors, although there are some barriers under the current system. Family Physicians may be taking care of the said patient’s family members. With their holistic and preventive approach, they will be able to care for the needs of the relatives of advanced cancer patients. Further studies exploring the views of family physicians in Hong Kong to provide such care should be considered. AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank all the participants and helper of the focus groups. This project was fully funded by the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians Research Fellowship 2009.

Lai-mo Yau, MBChB (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine) Correspondence to: Dr Lai-mo Yau, Department of Family Medicine and Primary

Health Care, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun

Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

Email: ylm017@ha.org.hk

References:

|

|