|

December 2019,Volume 41, No.4

|

Dr Sun Yat Sen Oration

|

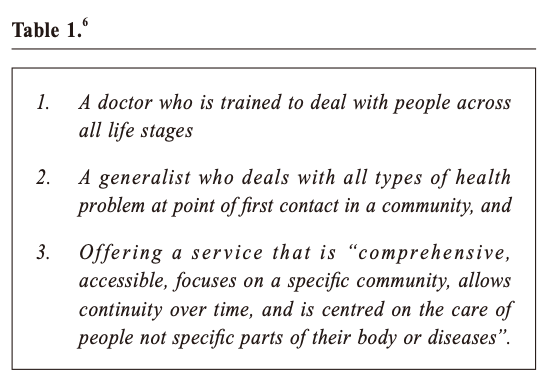

Identity, humanity and equity - three principles for modern timesAmanda Howe HK Pract 2019;41: 113-116 Acknowledgements:This article is based on the 30 th Sun Yat Sen Oration given by Professor Howe in Hong Kong in June 2019. Family doctors are always interested in people – so it is important to know something of the life and work of Sun Yat Sen,1 and his formative association with Hong Kong which underpinned his lifetime of struggle and achievement, both as a physician and as a leader. His reputation for establishing three principles that guided his values and actions led to the title of this article. 2 If we reflect first on ‘identity’, we can acknowledge that these is a tension between wanting someone with whom we identify - who can speak for us, make our voice heard, make us visible and respected in the world, makes us proud of what we have done and who we are: and the possibility of jealousy, or disagreement – “Why should she speak for me? Why is she so special?” Respect for our leaders is conditional on their earning our respect and expressing something that matters to us. We also need to acknowledge that fame is rarely lasting – a beloved figurehead can be forgotten, or a once popular representative may fail in a later election. We know that Sun Yat Sen did not have an easy time in his achievements – and we also know, as Dr Stephen Foo’s Oration two years ago explains3, that the birth and impact of the Hong Kong College was long in gestation and needed real persistence to achieve its current impacts on your health system. So any leader is only as good as the work that they did before their period of fame and influence, and any success in achieving a major social change will depend on more than one person’s efforts and vision. Another risk of defining one’s identity is the potential for rejection of the ‘other’ who is different. Male or female … old or young … black or white … there are many, many different people in this world, each one an individual, each with a story to tell. Many of our world’s problems stem from stigma, and from the definition of the other as ‘not like me’ – but we can choose to recognise our common humanity as a basis for an inclusive, shared identity. 4 The worldwide refugee crisis has made us acutely aware of the needs of those who are displaced, or disenfranchised, and makes us ask the question – who are our patients, who has a voice, who must we care for?.. even if they are not ‘our own’. An inclusive identity and a humane response allows us the charitable space to care for those who are in need, even if they are not part of our country: as doctors, we can respect and support all those who do this kind of work on our behalf, but this response is not universal. So how do we strike a balance that enables us to welcome and assist the other, as is our professional duty, while still having a strong sense of our own self and our worth? If you value something, how can you care for someone whose values or ideas are very different from yours? Psychologically, a secure identity stems from having consistent care by others when young, and so becoming secure in your own ability to interact with the world. 5 A mature adult can be responsive to others, be flexible, and accept challenge without excessive defensiveness, as can a mature nation. As family physicians, we need to become confident in our professional identity in order to meet our patients’ needs; because sometimes we must be willing to put aside our own personal identity to experience the world of the other. Empathy means putting yourself in the other’s shoes, feeling their dilemmas and reactions, and then assisting them to attain and retain a functioning adult self, while coping with the uncontrollable components of life and health. As a profession, we also need a firm identity - we need to be able to articulate, promote, and be proud of our unique characteristics (table 1) , while respecting and valuing those of others. Hence the need to be able to define family medicine, and its significance – it gives us an identity, it shows others what we can do – and gives us some structure and support when situations become difficult. So please learn how to explain our discipline to others – and then you will find you know yourself better.  We know that it is part of the valued role of an organisation like the HKCFP to express this identity, especially for younger doctors who are still trying to understand what it means to be a family physician in practice – or when politicians or other specialists do not clearly understand or appreciate what we do. The role of professional colleagues is to lead through membership, professional standards, and indeed in the media, to give family physicians an identity – a voice – and to show their value. The second principle highlighted here is humanity, which links with Sun Yat Sen’s principle of democracy. Democracy allows people a voice – to make choices, to be different, but also to have some control over their lives and destinies. Humanity in the context of professional practice equally celebrates difference – a humane physician accepts and understands the perspectives of others – but also stands for what is best, and aspires to what is possible, rather than accepting the status quo. A humane GP will care for all their patients – will offer them a voice, a choice, and some solutions – but will also strive for the best outcomes, and push for change where needed. They will try to help even their most damaged patients to succeed e.g. in overcoming drug addiction, or standing up against bullying … by helping them make good choices for lifestyle and selfcare: not overmedicalising distress, but helping them along a path to as good a quality of life and health outcome as possible. The principles of education, empowerment and enablement should be at the heart of our practice 7– giving patients a choice, but also supporting them as needed to make the right choices for themselves and their families. There also needs to be humanity at the level of the system. Just as Sun Yat Sen advocated for accountable and effective government, we also need to create strong health systems which support best practice. We cannot do what is right for our patients and populations without significant resources of time, expertise, and infrastructure. A good system will also make us accountable for the delivery of high quality care, ensuring that the human right to healthcare extends not just for those we like, or who can pay most, but for all – that is the purpose of Universal Health Coverage. 8 Across the world there are significant challenges here. Many do not yet have access to good quality care that is affordable, and that integrates their care and needs over time. This leads us on to the third principle – ‘equity’. I expect most readers are familiar with the Sustainable Development Goals9, which together if implemented could certainly make the world a much healthier place – and within which healthcare is only one component. Sun Yat Sen was determined to stabilise the material conditions needed for a healthy people, and all those of us concerned with health and healthcare need to think about the bigger social determinants of health.10 We know that poverty is a major risk factor for ill health and early morbidity and mortality, as the work of Guthrie, Mercer and colleagues show in their studies in Scotland.11We see many dimensions of inequity playing out in routine clinical practice, and we can recognise the conditions which routinely drive some into poverty and poor health, rather than maximising their potential and sustaining good health. At least some of our community of family physicians need to engage with agencies and issues beyond clinical practice, so that we can link with other agencies to impact on these upstream factors which so much affect our health. I would like here to note the work of the Wonca Health Equity Special Interest group 1, and to encourage as much activity at practice and College level as possible to address these issues. We can all play a part in equity in our own clinics by a commitment to quality improvement. Another important way to tackle hidden gaps is to check, through audits and data collection, about whether the system is having an equitable outcome for all.12 Where we find gaps, or groups who have less effective health care, we need also to choose the right solutions: we may need to address financing systems, different models of care, and also extend patient health education in order to achieve real universal health coverage. So, with these big aspirations, what other actions are useful? We can do more for the identity of our own profession, through ensuring excellent exposure to general practice in medical schools, strong postgraduate speciality GP training, and ongoing career development. We can ensure a focus on the needs of patients – measuring their experience of care, the quality of care (including continuity, addressing mental health as well as physical needs), and their overall inclusion in system (the equity issue as above). We can strengthen our own professional position by alignment with needs of others (governments, funders, W.H.O.), and by collecting the data needed to show what we achieve.13 Within Wonca, and indeed through many of our national membership bodies, we also explicitly try to address equity issues – for example, gender affects health differently, but also women and male doctors have different challenges in attaining a fulfilling career.14 We also need to campaign for research funding equity – and for ensuring that primary care can get the kind of evidence we need to inform our practice, rather than the funding being driven by commercial or technical interests.15 Finally, the work we do across countries and regions to develop family medicine is also a key effort to achieve a family doctor for all. Our discipline, as Barbara Starfield’s work showed16, is a route to equity – and better health care systems through stronger primary care can make a major contribution towards universal health coverage. In conclusion: unlike Sun Yat Sen, we are building a profession not a nation. We need to establish a strong identity as family doctors, and to ensure that the structures around us enable us to deliver on our values to the benefit, both for our colleagues and our patients. If we have confidence in that identity, in the value of our role as family doctors, then we have the professional capacity to act humanely – to go that extra mile, to make a new effort. Whether in our clinics, in professional advocacy, collecting stronger data, or helping another country, we are driven by our humane wish to see a better system, a better outcome for all. Some of that focus will be on those who are disadvantaged – and sometimes it will be our own profession that we have to advocate for: not in a self interested way, but to achieve the best. In this context, I want to remind all family doctors that the World Organization of Family Doctors (WONCA) is there to assist you in these efforts. And I know that all family doctors in Hong Kong will continue to be real role models in the region, and will continue to influence both the situation here and in other areas. I shall end by paralleling a quote from a speech by Sun Yat Sen, and I hope it is applicable for all of us - Now we want to revive our identity as family doctors, and use the strength of our members to fight against injustice; this is our mission. As the civilisation of the world advances and as mankind's vision enlarges, some say that professional identity becomes too narrow, unsuited to the present age, and that the future lies in other disciplines, and the new technologies. But I say that we must first establish our own identity, our own professionalism, and thus we can be a confident member of the whole health system, and reach out to others, using innovations to work together for change. Note: Wonca. WONCA Special Interest Group: Health

Equity.

Amanda Howe, OBE FRCGP Correspondence to: Professor Amanda Howe, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, Norwich Research Park, Norwich, Norfolk, NR4 7TJ, United Kingdom.

References:

|

|