|

December 2019,Volume 41, No.4

|

Original Article

|

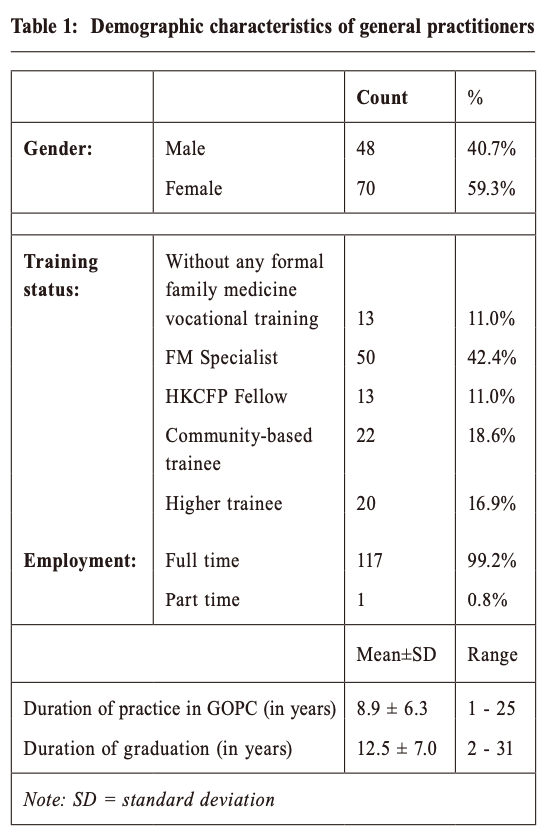

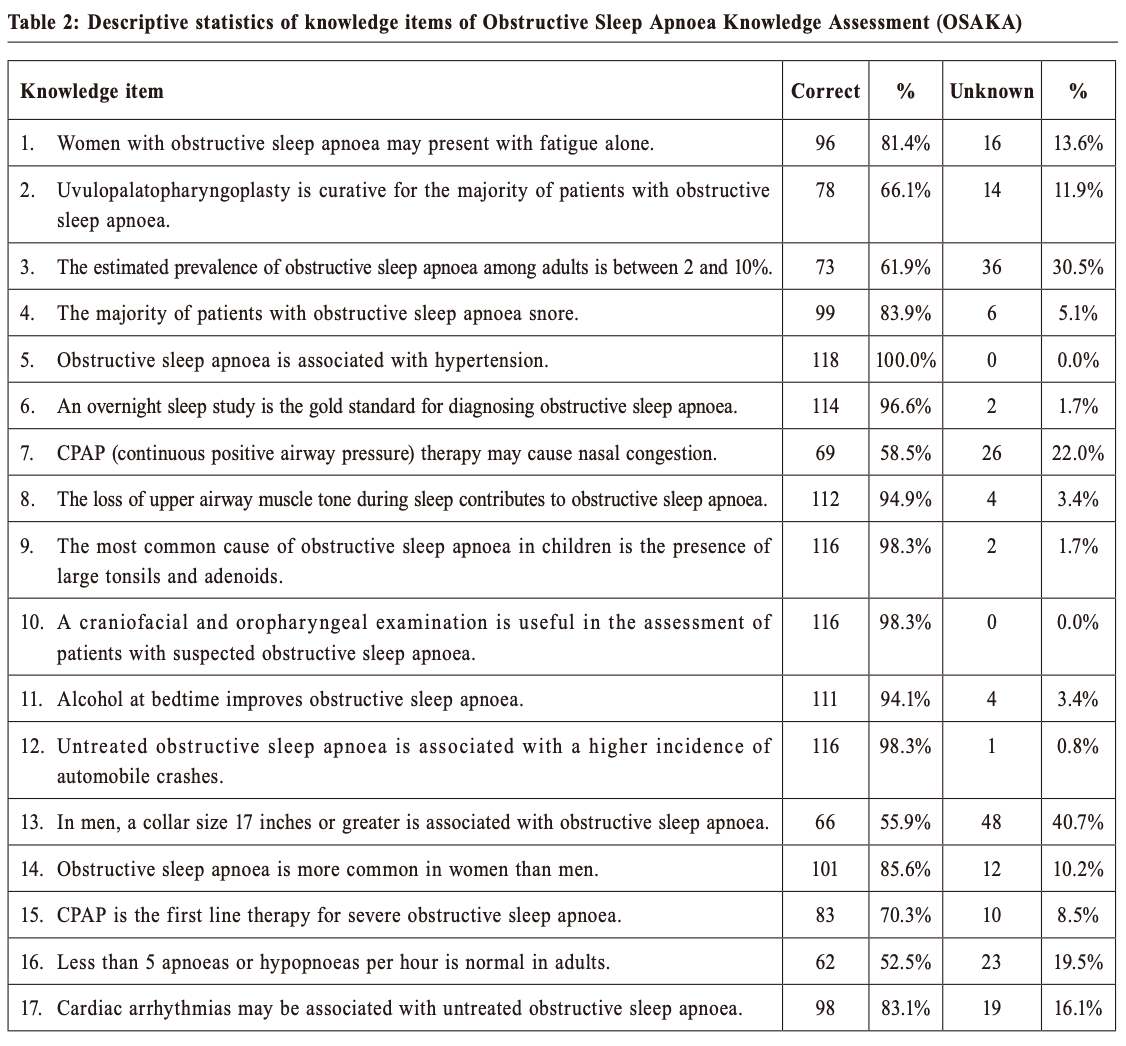

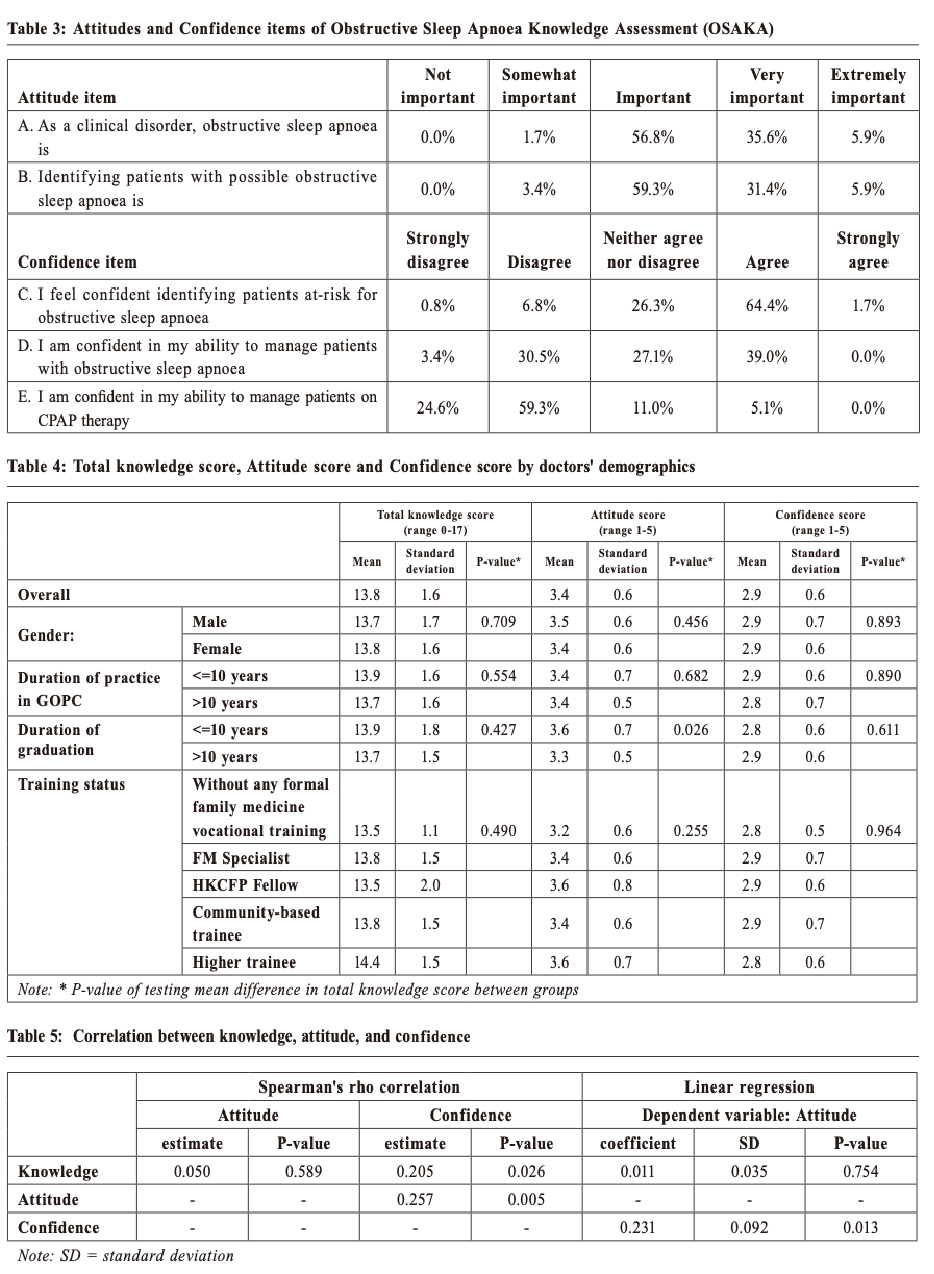

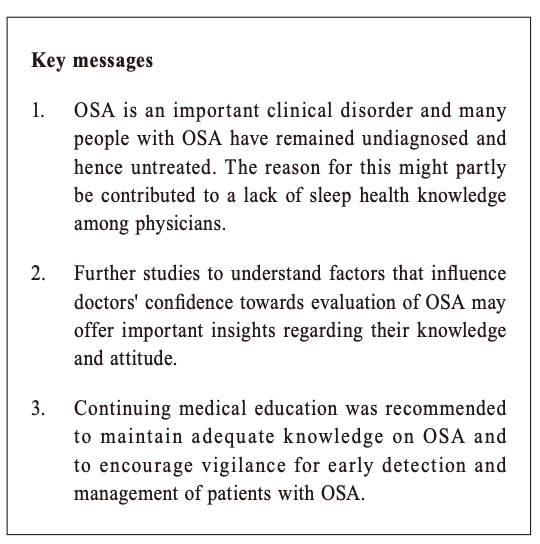

Attitudes and knowledge among general practitioners in Hong Kong about obstructive sleep apnoeaSamantha HK Chau 鄒凱琪,Carlos KH Wong 黃競浩 HK Pract 2019;41: 100-109 SummaryObjective: Keywords: Attitude, knowledge, obstructive sleep apnoea, family medicine, Hong Kong 摘要目的:澳本文章旨在研究香港全科醫生對阻塞性睡眠呼吸窒息症(OSA)的態度和知識。 關鍵字:態度,知識,阻塞性睡眠呼吸窒息症,家庭醫學,香港。 IntroductionAccording to the World Health Organization (WHO), obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) is a clinical disorder marked by recurring episodes of upper airway obstruction that leads to markedly reduced (hypopnea) or absent (apnoea) airflow at the nose or mouth. 1 In Hong Kong, the prevalence of OSAS is over 4% in men and over 2% in women ranging in age from 30 to 60 years.2, 3, 4, 5 Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is associated with many co-morbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular events and primary central nervous system (CNS) cancers, posing significant challenge to public health.6, 7, 8, 9 Unfortunately, an estimated 82% of men and 93% of women with moderate or severe OSA are, and have remained, undiagnosed.10, 11 “In-laboratory polysomnography” (sleep study) is the first-line diagnostic study when OSA is suspected. Polysomnography measures obstructive respiratory disturbance index (RDI), which is the number of obstructive apnoeas, obstructive hypopnoeas, and respiratory effort related arousals (RERAs) per hour of sleep. General practitioners (GP) are in an important position to detect and refer patients for OSA evaluation. However, overseas studies showed that many people with OSA have remained undiagnosed and untreated, which may contribute to the lacking of good knowledge of sleep health among the physicians.12, 16 It was noted that most primary care physicians lacked training in the diagnosis and management of OSA patients and there was significant under-recognition of this condition. 18 It was estimated that physicians were referring only 0.13% of their potential OSA patients for polysomnography, and it is likely that they are not identifying patients with mild disease, and may be missing patients with moderate to severe disease.12, What is more, many GPs lacked the confidence in being able to identify patients at risk of OSA.16 In order to improve the management of OSA, it is important to explore the current attitudes and knowledge of GPs. However, similar studies in Hong Kong are lacking. The objectives of the current study was to assess the attitudes and knowledge of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) among general practitioners working in the general out-patient clinics (GOPC) in Hong Kong. MethodsThe study was approved by the Kowloon West Cluster (KWC) Research Ethics Committee. This study involved the use of voluntary, self-administrated and anonymous questionnaires. Questionnaire administrationIn this cross-sectional study, all general practitioners working in KWC GOPCs except hospital-based trainees, who only needed to attend the GOPCs once per week, were included. A total of 168 Questionnaires were distributed manually by the doctor-in-charge of each clinic to all doctors working in the 23 different GOPCs in KWC of Hospital Authority (HA) during the period 1st May to 30th June 2016. The self-administrated questionnaire took approximately 5 to 10 minutes to complete. The completed questionnaires were mailed back to the author’s office via sealed stamped envelopes. A reminder was sent by email on 14th June 2016 to remind doctors to complete and send back their questionnaires. Questionnaire surveyThe validated questionnaires used in this study was developed by Schotland HM and Jeffe DB. 18,19The questionnaire was developed to assess physicians’ knowledge and attitudes concerning the identification and management of patients with OSA. The Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Knowledge and Attitude (OSAKA) questionnaire is a self-administrated paper that takes less than 10 minutes to complete. The OSAKA questionnaire consisted of 17 knowledge items and 5 questions relating to attitudes on OSA. The first section was about OSA knowledge covering five domains: (1) epidemiology, (2) pathophysiology, (3) symptoms, (4) diagnosis and (5) treatment of OSA. Participants were asked to indicate responses as “true”, “false” and “do not know”, which were scored as a correct or an incorrect response. The total knowledge score was computed as the percentage of correct answers to the 17 knowledge questions and ranged from 0% to 100%. The second section covered the attitude items. They included the view on the importance of OSA and one’s confidence in diagnosing and treating patients with OSA. About the view on the importance of OSA, it consists of 2 statements and participants were asked to indicate the importance of each outcome on a five-point Likert scale: “not important”, “somewhat important”, “important”, “very important” and “extremely important”. The view regarding one’s confidence in diagnosing and treating patients with OSA consisted of 3 statements and participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a five-point Likert scale: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. Both the attitude score and confidence score ranged from 1 to 5. All the questions were adopted without modification after revision. The demographic questions were modified according to the local condition. The original authors of the questionnaire has kindly approved the usage of their questionnaire in a written reply. Statistical analysisData analysis was performed using the ‘Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)’ version 20.0. Descriptive statistics was used to describe GP characteristics and responses to the individual questions on the OSAKA questionnaire. Spearman's rho correlation and linear regression were used to determine the relationship between knowledge score and attitude score. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant for all tests. ResultsOf the total of 168 questionnaires distributed, 118 completed questionnaires were returned with a response rate of 70.2%. Demographic characteristicsDemographic data of the 118 respondents is shown in Table 1. The mean number of years in GOPC practice and standard deviation (SD) were 8.9 and 6.3 years, with 99.2% reported working full time and 59.3% being women. The mean number of years of graduation and the SD were 12.5 and 7.0 years. Thirteen (11.0%) doctors had obtained Fellowship qualification and 50 (42.4%) doctors had obtained specialist qualification. 42 (35.8%) doctors were trainees in Family Medicine, of which 20 (16.9%) were higher trainees. (Table 1)  Knowledge Knowledge scores ranged from 0 to 17 (mean and standard deviation was 13.8 +/- 1.6). The mean of correct answers ratio was 81%. All respondents correctly answered the question about the association between OSA and hypertension. More than 90% of the respondents correctly answered an overnight sleep study is the gold standard for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnoea, the most common cause of obstructive sleep apnoea in children is the presence of large tonsils and adenoids, a craniofacial and oropharyngeal examination is useful in the assessment of patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea, and untreated obstructive sleep apnoea is associated with a higher incidence of automobile accidents on the road. On the other hand, only 52.5% of respondents correctly answered that less than 5 apnoeas or hypopneas per hour is normal in adults. (Table 2) There was no significant difference between total knowledge score and gender, duration of practice in GOPC, duration of graduation or professional status.  Attitude Attitude score was classified as Importance and Confidence scores. Among all respondents, a total of 98.3% answered that OSA was an important (56.8%), very important (35.6%) or an extremely important (5.9%) clinical disorder, and 96.6% reported identifying patients with possible OSA was important (59.3%), very important (31.4%) or extremely important (5.9%). In addition, 66.1% of all respondents felt confident in identifying patients at risk of OSA. However, only 39% felt confident in managing patients with OSA, and only 5.1% felt confident in managing patients with the Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) therapy. (Table 3) There was no difference in the total knowledge score or attitude score amongst the respondents’ gender, duration of practice in GOPC, duration of graduation and professional status. The attitude score demonstrated a significant difference between the respondents’ duration of graduation (p= 0.026). (Table 4) There was a positive correlation between knowledge and confidence (p= 0.026), and a positive correlation between attitude and confidence (p= 0.005) by Spearman's rho correlation. Attitude was positively correlated to confidence with linear regression’s coefficient 0.225 +/- 0.09. (Table 5)  DiscussionPrevious studies demonstrated that OSA is a multi-system disease. It has been increasingly recognised as an important medical condition leading to significant morbidity and mortality. This is related to the presence of twice as much hypertension, three times as much ischemic heart disease and four times as much cerebrovascular disease in patients with OSA. 21 However, oversea studies also found a low rate of recognition and diagnosis for sleep disorders in both community-based outpatient health settings and university-based clinics at the same geographical location in 2000.22 In the diagnosis of OSA, no single clinical factor is reliably predictive of this disease. However, combining clinical features and oximetry data, where appropriate, approximately one-third of patients could be confidently designated as having OSA or not. The remaining two-thirds of patients would still require more detailed sleep studies, such as full polysomnography, to reach a confident diagnosis.23 Studies that examined the knowledge and attitude of primary health care physicians towards sleep disorders were conducted in different countries among different specialties. OSAKA questionnaire was developed by Schotland HM in 200319, 20. To the best of our knowledge, there was no OSAKA survey data collected from primary health care physicians in Hong Kong. KnowledgeSchotland HM reported the correct score ratio was 76% among physicians from Washington University. Wang CL and Uong reported the mean total knowledge scores were 62% and 69.6%, respectively. 24-25In contrast, our questionnaire showed that the total correct score ratio was 81%, which was higher than previous reports done by United States (US) physicians. This finding might reflect the fact that Hong Kong doctors were more knowledgeable in OSA as compare to their counterparts in the US. Although all of the doctors correctly identified the association between OSA and hypertension, not all of them could recognise the majority of patients with OSA snore (83.9%) and that women with OSA may present with fatigue. Doctors in GOPC, as a gatekeeper for secondary health care, should be familiar with the early symptoms and signs of OSA. With early detection, disease progression and complications could be prevented effectively; henceforth reducing medical expenses in the long term. It was recommended that more time spent training both patients and doctors to look for warning signs of common sleep disorders and assess the risks associated with sleepy patients operating motor vehicles and/or other dangerous equipment. 26 More than one-third of doctors believed that uvulopalatopharyngoplasty was curative for the majority of patients with OSA, which was incorrect. Such beliefs could possibly delay referral of patients to specialist to initiate CPAP, which was the preferred treatment for patients with moderate to severe OSA. As a result, the challenge for doctors in the GOPCs is not only to learn how to detect OSA in patients who were at high risk of OSA, but also to refer these patients to specialists for further examination and treatment. AttitudeSimilar to overseas studies 16,19, we found that doctors in the GOPCs generally believed that OSA was important, very important or an extremely important clinical disorder (98.3%), and that identifying patients with possible OSA was important, very important or extremely important (96.6%). This might attribute to the fact that OSA had been increasingly recognised as an important medical condition leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Other studies have demonstrated that older physicians reported lower adherence to treatment guidelines for patients with diabetes mellitus 27 , and another study found a negative correlation between years in practice and OSA knowledge using the OSAKA. 19 However, there was no significant difference in the total OSA knowledge by years in practice (=<10 vs >10 years since graduation and =<10 vs >10 years since practice in GOPC) in our study. This might reflect a lack of adequate information regarding sleep disorders at the undergraduate and post-graduate medical education levels. In our study, the attitude score demonstrated a significant difference with regards to the respondents’ duration of graduation (p= 0.026). This might reflect that the physicians did not receive any special medical training on OSA since graduating from their respective medical schools. The training on OSA they received in medical school left little impression on them. We also found that there was a positive correlation between knowledge and confidence (p= 0.026), and positive correlation between attitude and confidence (p= 0.005). Attitude was positively correlated to confidence with linear regression’s coefficient 0.225 +/- 0.09. We believed that improving physicians’ knowledge on OSA was critical to improving OSA-related screening and treatment practices. Continuing medical education was recommended to encourage vigilance for the early detection, reporting of symptoms associated with OSA and management of patients with OSA.  Limitations The validated questionnaire adapted in this survey was designed by Schotland HM and Jeffe DB in the US, the knowledge items that assessed epidemiology might differ in Asia, therefore the knowledge score in general might also be affected. As the sample was taken from a homogeneous working group, the skewness of the obtained data might affect the result of the analysis to a certain extent. A large sample size, involving family doctors working in the HA setting or in Hong Kong, will be needed to increase the generalisation of this study. This was a cross-sectional study which assessed only association. Definite cause-and-effect relationship cannot be drawn due to the possibility of reverse causality. For the ‘attitude score’ and ‘confidence score’, they were treated as continuous scores instead of in the ordinal form for ease of calculation and interpretation. This study focused only on the doctor’s perspective, but the management of OSA involves patients and requires a multidisciplinary input. There might also exist the respondent’s self-report bias in this questionnaire survey. ConclusionMost of the surveyed doctors agreed that OSA was an important clinical disorder and that identifying patients with possible OSA was important. The positive side of the survey was that our questionnaire had a total correct score ratio of 81%, which was much higher than previous reports performed by US physicians. However, this study showed that many doctors were not confident in identifying patients at risk of OSA, neither were they confident in managing these OSA patients. Findings showed that there was a positive correlation between knowledge and confidence, and also between attitude and confidence. In order to screen for patients with OSA at the GOPCs, overnight pulse oximetry was an acceptable alternative for patients who are strongly suspected of having OSA and who do not have medical comorbidities (e.g. heart failure) that increase the risk of additional or alternative sleep related breathing disorders. Further studies to understand factors that may influence doctors’ confidence towards evaluation of OSA may offer important insights regarding their knowledge and attitude. In addition, continuing medical education was recommended to maintain adequate knowledge on OSA and to encourage vigilance for the early detection and management of patients with OSA. AcknowledgementThe authors would like to thank all participants in the questionnaire survey for their valuable insight and support, and Dr Sau Nga Fu, Dr Kit Yan Lee, and Dr Man Chi Dao, from the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Healthcare, Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. The authors would also like to acknowledge Professor Schotland HM and Jeffe DB for giving their permission for the OSAKA questionnaire to be used in this study.

Samantha HK Chau, MB ChB (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family

Medicine)

Correspondence to:Dr Samantha HK Chau, 11/F, Langham Place Office

Tower, Mong Kok, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|