|

June 2019, Volume 41, No. 2

|

Original Article

|

A survey exploration of the research interests and needs of family doctors in Hong KongWeng-yee Chin 陳穎怡, William CW Wong 黃志威, Esther YT Yu 余懿德 HK Pract 2019;41:29-38 SummaryObjective:

To examine the needs and interests of family doctors

regarding participation in primary care research

Keywords: Primary care; research capacity; research skills; attitudes; family doctors 摘要目的:評估家庭醫生對於參加基層醫療研究的需求及興趣。

關鍵字:基層醫療、研究生產力、研究技能、態度、家庭醫生 IntroductionIn most countries, the health of their population is directly linked to the quality of care that is provided by their primary health care system.1,2 Family doctors provide integrated, accessible health care services. They address a full range of personal health and health care needs, develop a sustained partnership with their patients and practice in the context of a family and community.3 In order to improve the quality of care, primary care providers need access to a wide range of relevant information to support their clinical practice. Unfortunately there is a relative paucity of research evidence regarding many common problems; in particular, problems that are managed almost exclusively outside the hospital settings. The majority of current research is mostly funded in academic tertiary and quaternary care hospitals.1 Furthermore, primary care doctors who provide front line services are typically not involved in generating or answering research questions that would be most relevant to their practice.4 There is a need to improve the quality and effectiveness of primary health care, but without research evidence, it is difficult to facilitate policy development in primary care.5 Traditionally, family doctors in clinical practice have not viewed research as an important component of their work and, in the past, Family Medicine trainees were not eager to do research.6 In a Canadian study published in 2002, 95% of medical graduates stated that they would never consider family medicine as a career if they were interested in research.7 More recently however, these attitudes have begun to shift as more medical schools and post-graduate training programmes implement greater emphasis and opportunities to incorporate research into their curricula, and the practice of evidence based medicine has become the norm.8,9 Some General Practice training programmes have now implemented a research training component for their trainees, such as through a participatory research process.10,11 Over the past 10-20 years, many countries have begun implementing strategies to build their primary care research capacity.12-14 In 2004, the American Academy of Family Practice stated, “Participation in the generation of new knowledge will be integral to the activities of all family physicians and will be incorporated into family medicine training. Practice-based research will be integrated into the values, structures, and processes of family medicine practices.”15 Around the same time, the WONCA Research Working Group made recommendations to prioritise research capacity building in primary care16 and in 2007 adopted the concept that every family practice in the world should be involved in generating new knowledge.13 Globally, there have been recent calls to further the primary care research agenda to guide health care and policy reform.17-20 In Hong Kong, until recently, there has been a greater focus on biomedical research with relatively less support and funding for primary care research. With recent health care reforms and attempts to strengthen primary care in Hong Kong21, more locally generated evidence is urgently needed. Hong Kong has a unique health care system with a wide variety of primary care practices and a unique set of patients and providers that need to be better understood. However little is known at this time how motivated Hong Kong’s primary care doctors are in contributing to local research and the drivers to facilitate greater engagement.22-24 The aim of this present study was to examine

the needs and interests of family doctors regarding

participation in primary care research, and to gain a better

understanding of the factors that could motivate greater

involvement and engagement in primary care research. The

objectives of this study were to: This study was initiated by the Research Committee of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians (HKCFP) to assess the potential of establishing a practice-based primary care research network and the research training needs of its members. MethodsStudy designAn online cross-sectional survey was conducted with three invitations to participate in the study sent from 11 November – 26 December 2016. Responses were accepted until 1 April 2017. Participants and samplingAll members of the HKCFP with emails were invited to join the study. Emails were sent from the HKCFP using their email mailing list. A third-party survey company, SoGoSurvey, was engaged to track the survey to ensure respondents remained anonymous. A unique identifying code was used for each invitation to ensure there was no duplication of respondents. Response rates were tracked by SoGoSurvey. In order to boost response rates, two further reminder emails were sent to all College members 14 days apart. Participants were awarded one CME point as an incentive for survey completion. The survey consisted of a combination of categorical

questions and items with Likert-scale responses, with

information on: Outcome Measures:

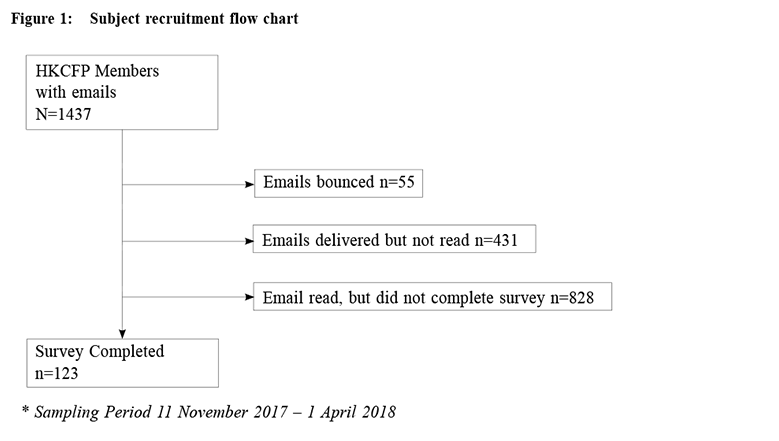

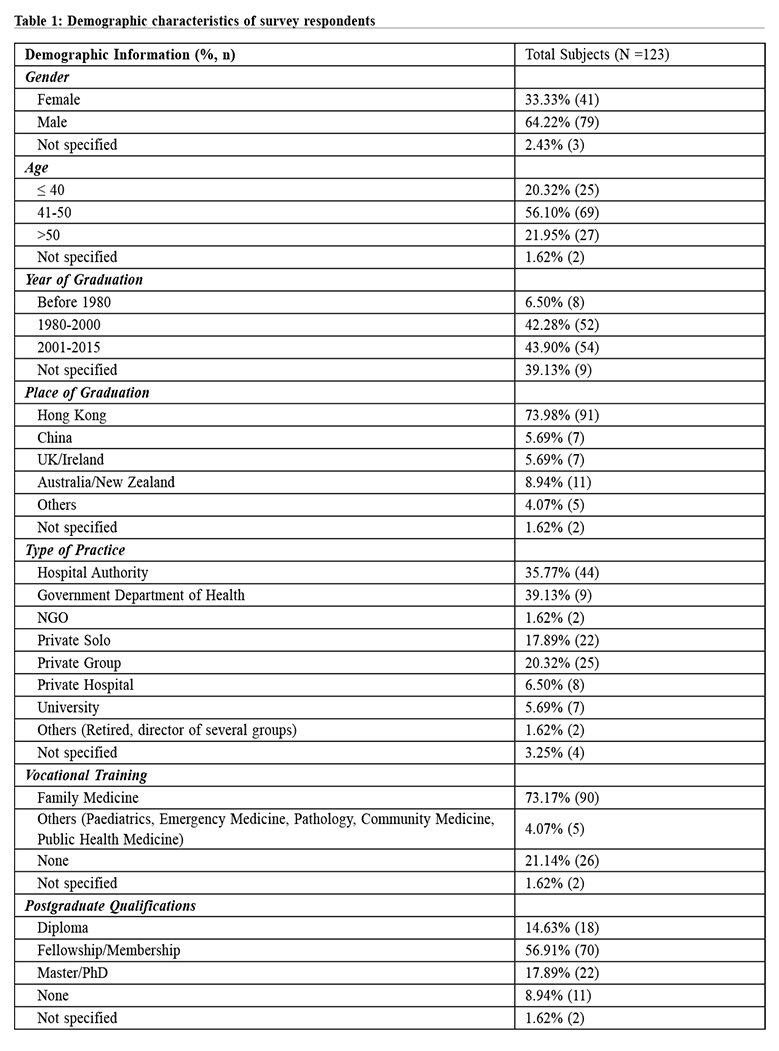

1. Engagement in research All data was analysed descriptively. Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 24 software. Ethics approvalThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong / Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster. ResultsResponse ratesFigure 1 outlines the subject recruitment process. A commercial survey company was used to administer and track the email responses anonymously using a unique identifying code. A total of 1,437 emails were initially sent out by the HKCFP office. Of these, 55 emails bounced immediately as the emails were no longer valid, 431 emails were delivered but not read and 828 emails were read but the survey was not commenced. By the end of the sampling period, 123 HKCFP members completed the survey. Subject characteristicsTable 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the survey respondents: 66% were male; 79% were >40 years; and 75% graduated from a medical school in Hong Kong; 37% worked for the Hospital Authority; and 74% were vocationally trained in Family Medicine. Over half of the respondents had previously received research skills training either in medical school, through postgraduate studies, or through experiential participation in research.

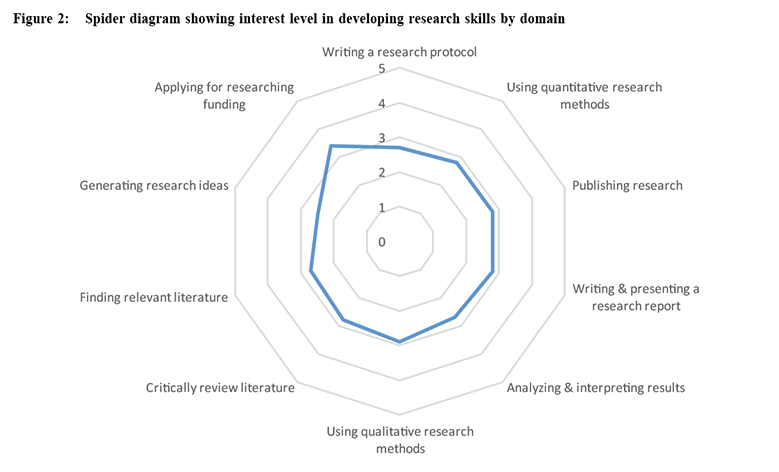

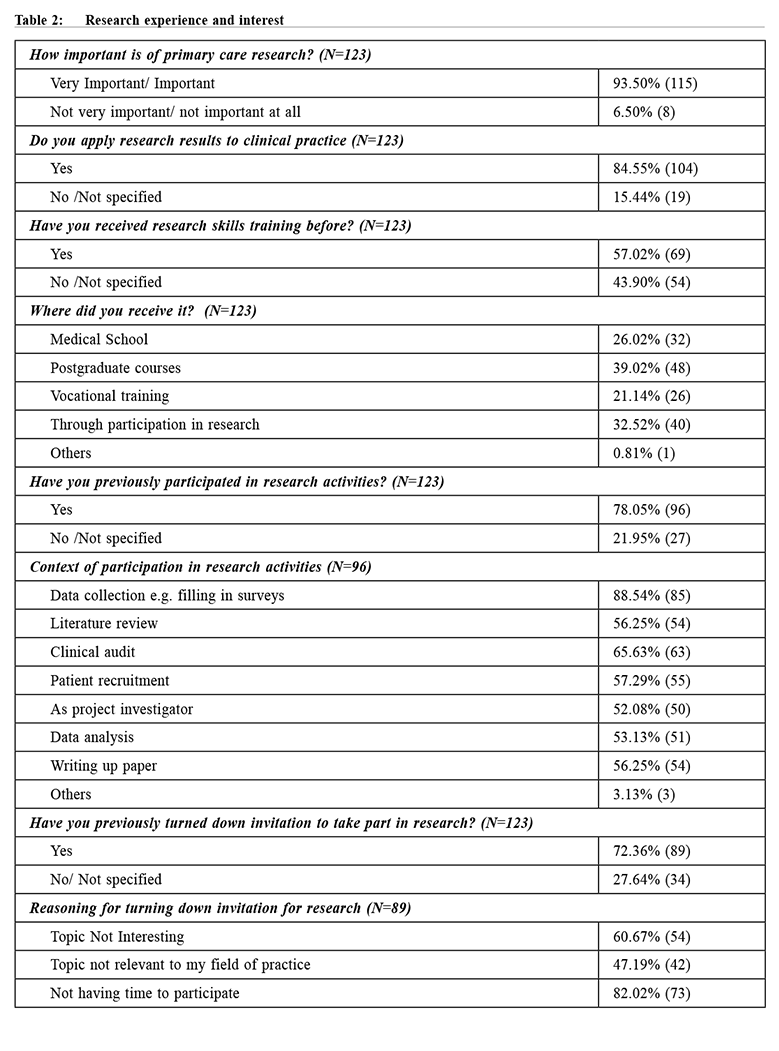

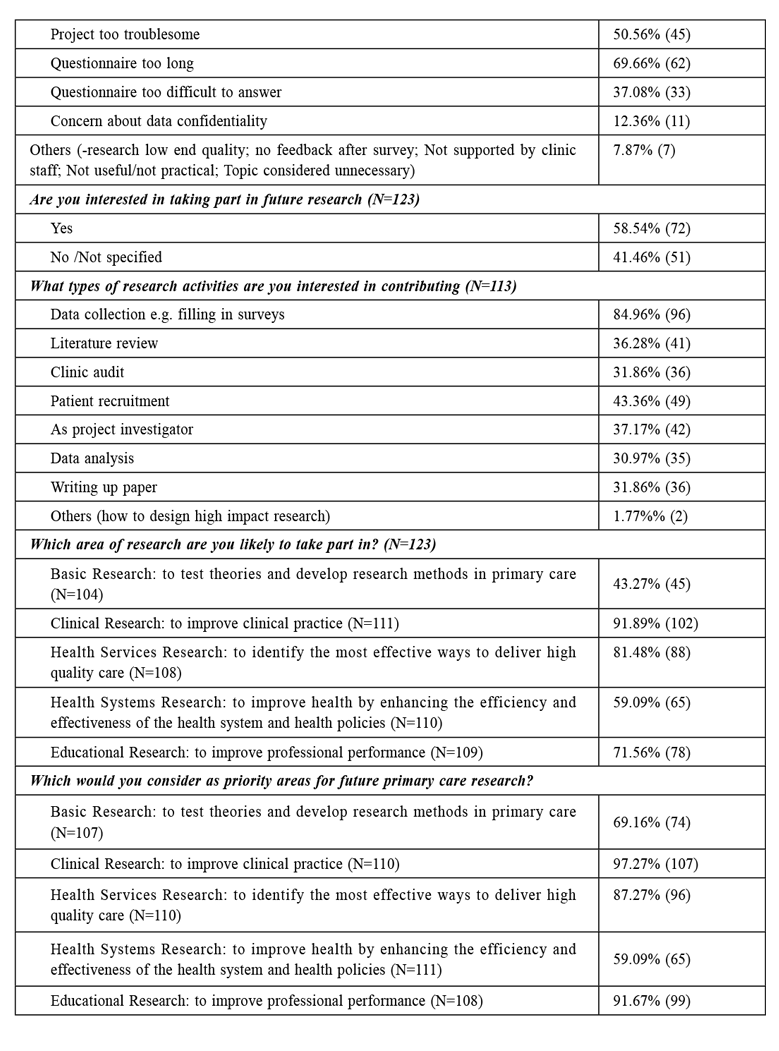

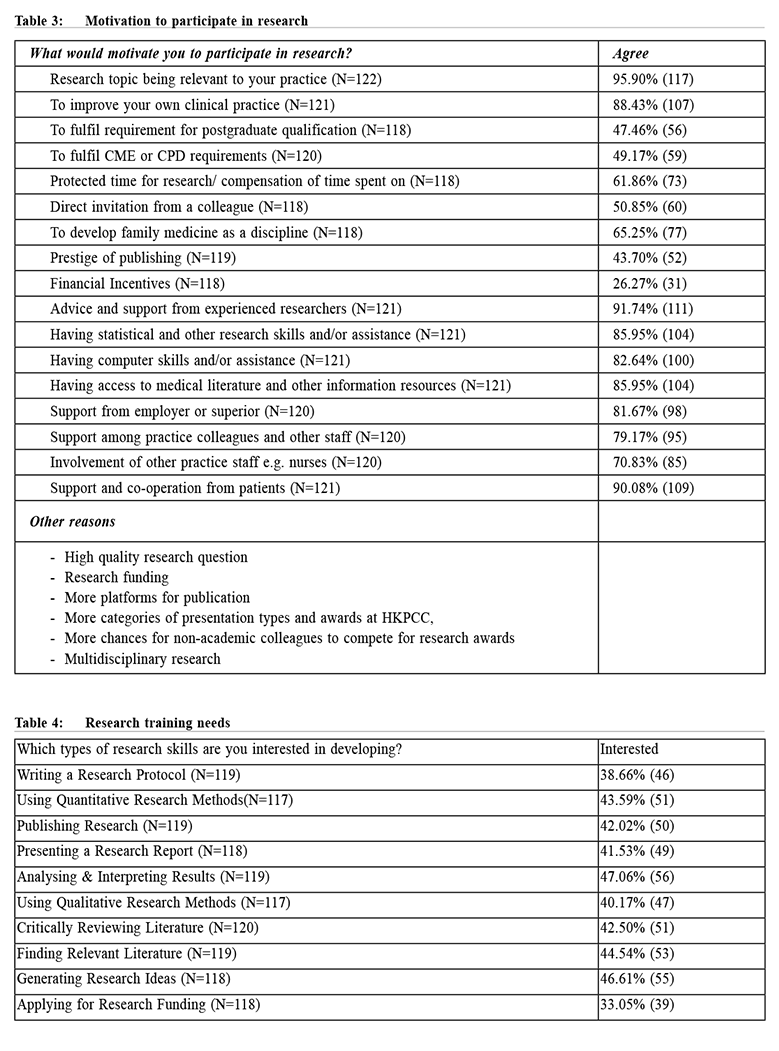

Research Experience and Interest Table 2 shows the research experience and interests of the 123 respondents. Almost all respondents agreed that primary care research was important with 85% reported that they regularly applied research-based evidence to their clinical practice. Of the 123 respondents, 69 had previously participated in research activities, most frequently by assisting in data collection or performing clinical audits. Conversely, 89 reported that they had previously turned down invitations to take part in research mainly due to lack of time, tasks being too troublesome, or lack of interest in the research topic. When asked about interest in participating in future research projects, 72 respondents reported that they would be interested in conducting either clinical and health services research, or medical education research. Motivation to participate in researchTable 3 shows the key drivers to research participation. The commonest options were: relevance of the research topic to their own practice, access to advice and support from experienced researchers, and support and co-operation from patients. Interest in Research skills trainingTable 4 and Figure 2 shows the spider diagram which illustrated the interest level of various research skills training.25 There was an even interest level over all the research skills training options offered, with the best interest in generating research ideas, data analysis and interpretation. DiscussionThis survey was a pilot exploratory study to examine the perceptions and interests among Hong Kong family doctors regarding research participation. It will help to inform the HKCFP of the feasibility and potential for establishing a research network and to identify the key research training needs of its members. Although only 123 HKCFP members responded to this survey, it is encouraging to see that there was sufficient research interest from doctors of a wide range of demographics, including from both public and private sector providers. This is important when establishing a research network; a wide variety of practices can make research findings more generalisable.

From our findings, it appears that our respondents were already engaged in research in many ways, aligning with Paul Glasziou’s “research engagement triangle”.26 Firstly, there was a large pool of “research users” comprising almost all our respondents. Ideally, all clinicians should consciously incorporate research into their clinical practice, such as in the form of management guidelines or practice evidence-based medicine. Secondly, there was a moderate pool of approximately 50 respondents who reported to be ‘participants in research’. These respondents had engaged in research in many tangible ways, such as conducting literature reviews, data analysis and writing manuscripts. Interestingly, a number of respondents had been “project investigators”. This indicates that a pool of family doctors are ready to be groomed to become future ‘research leaders’ whose task is to design and publish research.26 Although larger numbers of workers are needed to reach a critical mass where territory-wide research projects can then be sustainable, it appears that already a pool of family doctors in Hong Kong are already willing to engage further in research. Barriers against participating in primary care research have previously been identified in the literature, such as availability of protected time to conduct research, impact on income, and general attitudes and willingness towards research.20-23 In this study, however, most of the barriers reported by our respondents were more related to the practicalities, such as research skills, availability of mentorship, and ease of subject recruitment. Many of the respondents reported intrinsic motivation to participate in research such as good research questions relevant to their field of practice. Respondents also reported a willingness to participate in translational research, such as in clinical and health services research or medical education research. External motivators, such as protected time to do research, CPD points or financial incentives, rated lower. All these indicate that within our sample of respondents, there was a high degree of willingness to engage in research, and the motivations tended to be altruistic. Over half of our respondents reported that they had had already received some research skills training either in their undergraduate or postgraduate training or experientially by participation in research in the past, but there was still significant interest in further research skills training. Given sufficient opportunity, support and mentoring, this group of doctors are ready to embark on research collaborations for clinically relevant questions that can enhance patient care. Hong Kong could make references from Australia, by using a staged approach.27 Firstly, by increasing awareness, capability and skills to non-participants of research to increase our pool of participants. Next, by offering more opportunities to increase research skills through formal training and participation in research collaborations. Then, increase the intensity of research training through higher qualifications, publications and supervisory skills. Finally, by nurturing the growth and development of primary care academics.27 Our findings show that many family doctors in Hong Kong are at varying stages of development. One way to enhance research capacity may be to offer more opportunities for research training and research collaboration. LimitationsThere were several limitations to this study. This was a voluntary survey, and the participation rate was low. Characteristics of the respondents demonstrated that they had had pre-existing interest in research, some of them had prior research experience and training. With such a biased sample, our findings cannot be extrapolated to all family doctors in Hong Kong. However, our findings do indicate that sufficient interested doctors in diverse practice settings are there, to initiate a primary care research network or collaboration. ConclusionThis study was a pilot exploration of the interests and needs of Hong Kong family doctors towards participation in primary care research. As only 123 respondents completed the survey, our study findings cannot be generalised to all family doctors in Hong Kong; however, it indicates that there is some interest in primary care research and that some family doctors in Hong Kong are keen to increase their research capabilities. In order to build Hong Kong’s primary care research capacity, this willingness to engage in research needs to be capitalised, and it appears that there may be a role for bodies such as the HKCFP or other academic institutions to facilitate this growth. AcknowledgementsMuch appreciation goes to the colleague at the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians, Priscilla Li, who sent out the survey emails to the members of the HKCFP. Acknowledgements to Dr Yvonne Lo who developed several questionnaire items in the survey by using previous unpublished study to examine what motivates family doctors to engage in research, and to Ms Karina Chan who assisted in the development of the survey and with the data analysis. Disclosure of potential conflicts of interestThis study did not receive any funding. All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Weng-yee Chin, MBBS (UWA), MD (HK), FRACGP

William CW Wong, MB ChB(Edin), MD(Edin), Specialist in Family Medicine

Esther YT Yu, MBBS (HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Correspondence to: Dr Esther YT Yu, Department of Family Medicine and Primary

Care, The University of Hong Kong, 3/F., Ap Lei Chau Clinic,

161 Main Street, Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|