|

March 2019, Volume 41, No. 1

|

Update Article

|

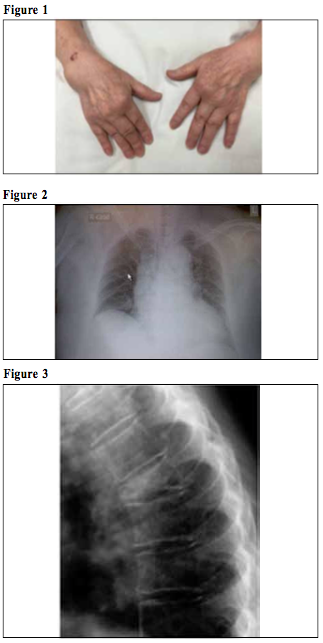

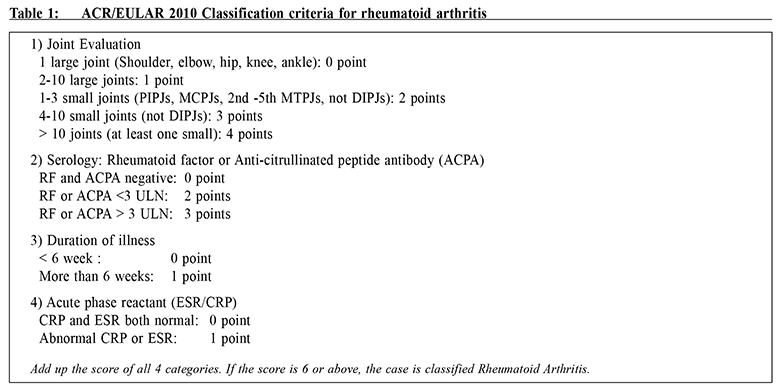

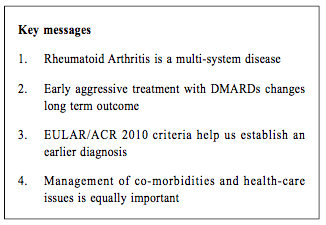

Update on Rheumatoid ArthritisCheuk-wan Yim 嚴卓雲 HK Pract 2019;41:11-17 Summary Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease which results in damage to joints as well as to multiple organs. The American College of Rheumatology / European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) 2010 Classification criteria help physicians to diagnose RA early. Conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and biological agents have improved RA's long-term outcome. Early aggressive treatment is now considered the standard of care. The task of managing the various co-morbidities and healthcare issues of RA is challenging which would require close collaboration between rheumatologists and family physicians. 摘要 類風濕性關節炎(RA)是一種自身免疫性疾病,除了會影響患者的關節外,隨著病情演進,其他的身體器官,亦可能受到不同程度的影響。American College of Rheumatology / European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) 2010分類標準可幫助醫師儘早診斷RA。傳統的改善病情抗風濕藥 (DMARDs)和生物製劑改善了長期的結果。早期的積極治療現在被認為是護理的標準。管理RA的各種合併疾病和保健問題的任務是具有挑戰性的,這需要風濕病學家和家庭醫生的密切合作。 Case vignetteMs Chan is a 56-year-old housewife, non-smoker and non-drinker. She suffered from diabetes mellitus and hypertension and was under the care of her private family doctor. She developed symmetrical arthritis affecting both wrists, finger joints (metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints and knees) in 2013. Her family doctor suspected that she was suffering from rheumatoid arthritis and referred her to a Rheumatology clinic for review. However she defaulted SOPD appointment and simply took over-the-counter 'painkillers' which contained indomethacin and prednisolone. In 2015 she was admitted into the Medical ward of her local Hospital Authority (or private) hospital for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). She was noted to have early deformities of both hands with active arthritis (Figure 1), mild pulmonary fibrosis and cardiomegaly (Figure 2), collapsed lumbar vertebra L1 and 2 (Figure 3). Blood test revealed rheumatoid factor 960 (ref <12), ESR 96 mm/hr, CRP 26 (ref<8). She was diagnosed as suffering from severe Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) with joint deformities, interstitial lung disease, osteoporosis and coronary artery disease ( CT coronary angiogram showed multiple calcified plaques at all coronary arteries with significant stenosis).

She was initially treated with sulphasalazine for her rheumatoid arthritis, denosumab for her osteoporosis, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) followed by clopidogrel, aspirin, losartan, atorvastatin for her coronary artery disease. However, her arthritis remained active at 6 months. Abatacept injection as self-financed item was added. Her rheumatoid arthritis responded well to treatment, with resolution of arthritis and normalisation of ESR and CRP. Her functional status was restored and her RA remained in remission. IntroductionRheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease that primarily causes chronic inflammation in the joints. The pictures of symmetrical polyarthritis leading to progressive multiple deformities of limbs have been the hallmark features of RA. However, it is a multisystem disorder which may cause complications in various organs and tissues. With the rapid advances in diagnostic tools and the therapeutic options in the past two decades, we are now more confident in the ability to induce remission of the arthritis, restoration of function and prevention of deformities in our patients. Early identification of cases at the primary care by means of new diagnostic tools and prompt referral to rheumatologists would enhance the treatment outcome. Epidemiology and etiologyThe annual incidence of RA varies from 5 to 50 every 100,000 population1,2,4. The global prevalence is between 0.3-1.0%.3,5 Hong Kong has a reported prevalence of 0.35%.6 RA affects all ages, with peak between 35 and 50 years old. The exact cause of rheumatoid arthritis remains unknown. Current evidence suggests that it is a multifactorial disease. Genetic, environmental, hormonal, immunologic, and infectious factors may play significant roles in the initiation and perpetuation of this illness. First-degree relatives have a 2- to 3-fold increase in risk7 while the concordance rate in monozygotic twins is approximately 15-20%.8,9 Individuals having certain shared epitopes of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) are at an increased risk (e.g. HLA-DR beta *0401, 0404, or 0405, HLA-DR beta *0101)10,11. Females are affected approximately 3 times more often than males12 but the difference diminishes in older age groups, suggesting the possible role of sex hormones. Cigarette smoking has been shown to promote citrullination of peptides in the lungs13, which would trigger the production of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) production. Various infectious agents (such as Epstein-Barr virus, Mycoplasma species) have been postulated for decades to have an association. There is emerging evidence pointing to an association between RA and periodontopathic bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis14,15, and treating the gum disease has been shown to improve RA.16 PathophysiologyRecent histopathological and immunopathological studies envisage RA as a clinical syndrome with different subsets. These subsets represent various dysregulatory interaction of helper T-cells, B-lymphocytes, macrophages and fibroblasts, as well as the consequent pro-inflammatory cytokines such as Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-10, IL-18, Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF)-alpha.17,18 They all lead towards a final common pathway in which persistent synovial inflammation and associated damage to articular cartilage and underlying bone are present.18 While the majority of RA would have rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA), around 20% of the cases would be double-negative19. For the same reason, certain inflammatory parameters such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein level may be normal in some active cases. Clinical presentationThe classical presentation of RA is persistent symmetrical polyarthritis that affects the hands and feet. However, the distribution of joint involvement at disease onset is quite variable. Most of the cases would start as arthritis in one or few joints with gradual progression to other joint areas in the subsequent weeks to months. Small joints of the hands (including wrists) and feet are the most common, followed by elbows, knees, ankles and shoulders. Some patients may begin with systemic features (e.g. fever, malaise, arthralgias, and weakness) before the appearance of overt joint inflammation and swelling. A small percentage (approximately 10%) of patients have an explosive onset of polyarthritis and extra-articular manifestations. On physical examination, the typical swelling, tenderness, warmth, and decreased range of movements (ROM) of the affected joints would be present. There may be wasting of muscles around the joints, of which interosseous muscles of the hands being the most frequent. Deformities such as ulnar deviation, boutonniere and swan-neck deformities, hammer toes, and joint ankylosis may be present in advanced cases. RA is a multisystem disorder. Inflammation and damage may occur in skin (rheumatoid nodule, vasculitis), eyes (episcleritis, scleritis, sicca syndrome), lung (interstitial lung disease, pleuritis and pleural effusion), heart (pericarditis and pericardial effusion). Active RA is associated with subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and stiffness. Large cohorts have confirmed rheumatoid arthritis as an independent cardiovascular risk factor.20,21,22 In the Fracture Risk Assessment Tools (FRAX) for osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis has a significant weighing on the overall fracture risk.23,24 In additional to the multi-organ involvement, pain and functional decline frequently lead to emotional instability, depression and unemployment in the individuals, and cause profound socioeconomic impact to society. Autoantibodies in RAi) Rheumatoid factors (RF) are autoantibodies directed against the Fc fragment of immunoglobulin (IgG) G molecules. They are present in 70-80% of RA cases.25 However, RF may be present in a variety of other conditions such as infectious mononucleosis, chronic hepatitis, leukaemia, Dermatomyositis, SLE, Sjogren, systemic sclerosis. The specificity of RF for RA is only 85%. ii) Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) are antibodies directed against citrullinated proteins. Proteins (e.g. fibrin, vimentin) can undergo citrullination during cell death and tissue inflammation. ACPAs have been demonstrated to predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis26,27, more active and severe disease course, more aggressive radiological damage.28 They have a sensitivity of 50-80% and specificity of 95-98% for RA. DiagnosisThere is no single confirmatory test for RA. The diagnosis is established by a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging features. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 criteria had been used for more than two decades.29 They were limited by poor sensitivity and specificity for patients with early inflammatory arthritis who subsequently developed rheumatoid arthritis. Thus the ACR and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) jointly proposed a new set of criteria in 201030 which has a better performance in the identification of early cases.31,32 In the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria, the patients must 1) have at least 1 joint with definite clinical synovitis (swelling) 2) with the synovitis not better explained by another disease There are 4 categories of assessment (Table 1): a) Joint involvement (score 0-5) b) Serology (RF or ACPA, score 0-3) c) Acute phase reactant (score 0-1) d) Duration of symptoms (score 0-1) The maximum number of points possible is 10. A classification of RA requires a score of 6/10 or higher. Patients with a score lower than 6/10 should be reassessed over time. If patients already have erosive changes characteristic of RA, and they meet the definition of RA, application of this diagnostic algorithm is unnecessary. This set of criteria has a better performance in the identification of patients with early arthritis. They subsequently evolve into rheumatoid arthritis and these criteria are currently used in the RA studies and guidelines. Imaging in Rheumatoid arthritisRadiographyPlain radiography remains the readily available and inexpensive choice for RA.33 Views of the hands, wrists, knees, feet, elbows, shoulders, hips, cervical spine, and other joints should be assessed when indicated. Erosions may be present even in the absence of pain. However, the radiographic changes lag behind the disease process in RA by months or even years and change after treatment is slow. Other imaging with better dynamic changes to therapy would be warranted. Ultrasonography (US)Musuloskeletal (MSK) ultrasonography is an attractive method of imaging for RA.34,35 The operating cost is relatively low. It is free from harmful radiation. The advances in US imaging technology may permit better imaging of inflamed joints which can differentiate joint effusion, synovial proliferation, tenosynovitis and erosions.35 With the Doppler technology, the rheumatologist can monitor disease progression treatment response.36 Moreover, US-guided aspiration, biopsy and injection of medication are low risk intervention that could be performed in the day-care setting.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) MRI offers excellent detection and differentiation of soft-tissue, effusion and erosion at an early stage.37 However, it is a more expensive investigation comparing with X-ray or MSK ultrasonography. Currently low-field MRI machines (of 0.2-0.5T) targeting at peripheral joints are capable of detecting inflammatory signals.38 Treatment optionsOnce the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis is established, disease modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs (DMARDs) should be started as soon as possible.39, 41 The goal of treatment should be aimed at achieving sustained remission or low disease activity in every patient40, restoring the function of the affected joints and preventing deformities as well as systemic complications. Currently available DMARDs are classified under three categories: conventional synthetic DMARDS, biological DMARDs and target synthetic DMARDS. Conventional synthetic DMARDS (csDMARDs)Methotrexate, leflunomide, sulphasalazine, hydroxychloroquine are common treatment choices that are used alone or in combination. Methotrexate (MTX) is the first-line choice in RA because many clinical trials have clearly established its short and long-term efficacy.42,43,44,45 The relative efficacy to safety profile of methotrexate in RA is superior to other DMARDs. Regimens using MTX in combination with other DMARDs (cs-, b- or ts-) have been shown to be more effective than MTXmonotherapy or b-/ts-DMARD monotherapy.46-49 Thus methotrexate is considered as the ‘anchor drug’ in RA. Leflunomide (LEF) and sulphasalazine (SSZ) are alternatives for moderate to severe RA who cannot tolerate or when MTX is contraindicated. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is usually used in mild RA cases or in combination with MTX. Other csDMARDs include cyclosporine A, azathioprine, penicillamine, and gold salt may be used in selected cases of RA Biological DMARDs (b-DMARDs)Biological DMARDs (b-DMARDs) are monoclonal antibodies or receptor proteins targeting at specific inflammatory cytokines. At the moment there are 4 classes of agents available: 1) TNF inhibitors- adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab 2) anti-CD 20 antibodies - rituximab 3) T-cell co-stimulatory inhibitor - abatacept 4) Interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitors- tocilizumab They offer more rapid onset of action and better efficacy than cs-DMARD alone. However, they are expensive items and are listed as self-financed items in the public health care system. Patients whose disease remain highly active despite trying several csDMARDs and/or are having financial difficulty may be referred to apply for subsidy for b-DMARDs under the Samaritan Fund Scheme. Target synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs)These novel agents, also called small molecules, inhibit the signal transduction of the inflammatory cytokines through intracellular kinase (Januse kinase or JAK) pathways. Tofacitinib is a JAK 1 & 3 inhibitor which is an oral preparation proven to be effective as monotherapy or in combination with MTX.49 EULAR recommendation:The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) has published recommendations on the treatment algorithms of RA50: Pre-treatment assessmentBaseline investigation including complete blood count, renal and liver function test, X-ray of affected joints and Chest-X-ray would be performed in all RA patients. As Hong Kong has a high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection and the fact that various DMARDs and corticosteroid may impose low to high risks of hepatitis B reactivation, hepatitis B serology is mandatory. For patients who plan to receive biological or target synthetic DMARDs, additional screening for latent TB infection (with Tuberculin skin test or Interferon Gama Release Assay), assessment of cardiac profile and counselling on the risk of herpes zoster is necessary. Monitoring of disease activity and side effectsAccording to the recommendation of ACR and EULAR, the patients should be assessed every 1 to 3 months for treatment response and adverse events.39, 50 If there is no improvement by 3 months after the start of treatment, or the target (remission or low disease activity) has not been reached by 6 months, the DMARDs should be escalated or adjusted. There are numerous disease activity measures to assess the disease severity: Disease Activity Score-28 joints (DAS 28), Simple Disease Activity Index (SDAI), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) are some of the widely used tools in clinical practice*.51

As the DMARDs may give rise to various adverse events, it is important to alert the patient to take note of any skin rash (especially after HCQ, SSZ, LEF, or b-DMARDs are used), oral ulcer (MTX, LEF, azathioprine), hair loss (MTX, azathioprine), visual problem (HCQ). Regular blood test should be performed to screen for hepatitis (MTX, LEF, SSZ, tocilizumab, tofacitinib), leucopenia (MTX, LEF, tocilizumab, tofacitinib), hyperlipidaemia (tocilizumab, tofacitinib). Common viral (e.g. URTI) and bacterial infection (pneumonia, urinary tract infection, soft tissue infection) would occur more frequently. Tuberculosis, herpes zoster and other opportunistic infections may occur. General advice including smoking cessation, healthy diet and habits, avoidance of crowded places, wearing mask if necessary should be offered to minimise the risk of infection. Concerning vaccination, killed vaccines (e.g. pneumococcal/ influenza/Hepatitis B) are generally safe52* while recombinant vaccine (e.g. Human Papilloma virus) is probably safe in patients on DMARDs. Live attenuated vaccines (e.g. MMR, zoster) are not recommended if the patient is receiving biological DMARDs*.39,52 Role of primary care practitioner in the management of RAIn order to capture the window of opportunity of early aggressive treatment, early referral of patients with clinical diagnosis of RA to rheumatologists is important. Primary care practitioners play a pivotal role in the identification of cases by performing autoantibody testing (RF or ACPA) and inflammatory markers (ESR or CRP) on patients with arthritis matching the distribution of RA according to the EULAR/ACR criteria. The medical history including hepatitis status, other medical illnesses, family history and allergic history are valuable. With sufficient information the rheumatologists can triage the cases for an early assessment and initiation of treatment. While the patient is waiting for the rheumatology appointment, prescription of analgesics and arrangement of physiotherapy would alleviate symptoms. Moreover, primary care physicians can manage the co-morbidities of the patients (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases) in collaboration with the rheumatologists so as to provide the most suitable treatment and minimise the complications. Furthermore, the provision of care and advice on smoking, dental care and vaccination would have significant impact on RA management. ConclusionsRheumatoid Arthrits is an autoimmune disorder that can cause joint deformities, multi-organ involvement, increased risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporotic fracture. ACR/EULAR 2010 classification criteria help the identification of early RA cases. Early initiation of DMARDs and intensive monitoring with appropriate drug titration is essential to treat the disease to achieve remission, restore the function and prevent complications. The biological and target synthetic DMARDs have expanded the armamentarium of RA. The concerted collaboration between primary care practitioners and rheumatologists is essential to optimise the management of RA. Hopefully the images of advanced RA would soon become history.

Cheuk-wan Yim, FRCP(Edin.), FHKCP, FHKAM

Correspondence to: Dr Cheuk-wan Yim, Department of Medicine, Tseung Kwan O Hospital, 2 Po Ning Lane, Hang Hau, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|