|

Sept 2020,Volume 42, No.3

|

Case Report

|

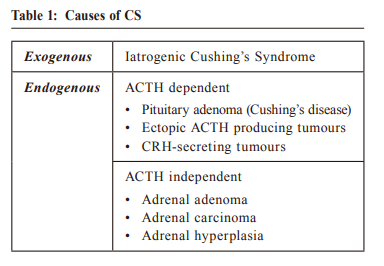

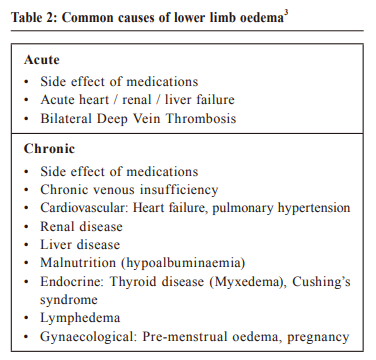

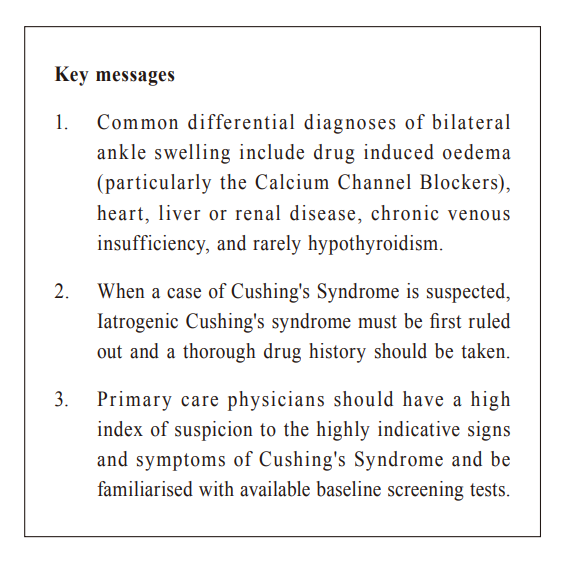

Iatrogenic Cushingʼs Syndrome presented with bilateral lower limb oedema: a case reportWing-yee Siu 蕭頴怡, Catherine XR Chen陳曉瑞, Ting-kong Poon潘定江 HK Pract 2020;42:70-72 SummaryDiagnosing Cushing's Syndrome (CS) in primary care is often difficult because few of the symptoms or signs are pathognomonic and most are non-specific. Here we report on a case of a patient who presented initially in primary care with bilateral lower limb oedema. 摘要在基層醫療中診斷庫欣氏(Cushingʼs)綜合征(CS)往往比較困難,因為該病幾乎沒有特異性的症狀或體征,大多數都是非特異性的。本文報告了一例最初以雙下肢水腫到基層醫療就診的患者。 IntroductionCushing's Syndrome (CS) refers to a collection of signs and symptoms resulting from chronic exposure to excess glucocorticoid. Presentation of CS varies and could involve multiple systems, and its diagnosis usually requires biochemical confirmation. In this case report, we re-examined the diagnostic process of a case of CS presented to the General Out-Patient Clinic (GOPC) with bilateral lower limb oedema. The caseA 65-year-old lady with a history of well controlled hypertension presented to a Hong Kong Hospital Authority GOPC with bilateral lower limb swelling of a few weeks duration. She is a non-smoker and non-drinker, with no known drug allergy. The lower limb swelling was present throughout the day and not associated with pain or redness. During this period, she was also noted to have higher home blood pressure readings than usual. She has been on Amlodipine 5mg daily for the past few years with noted good drug compliance. There was no recent change in this drug’s dosage. There was also no cough or short of breath, no frothy urine or other urinary symptoms, no chest pain, orthopnoea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea and no cold intolerance or malaise. On physical examination, her general condition was noted to be satisfactory, but with an obese figure of BMI 29.3 kg/m2. General inspection showed a round moon face with truncal obesity. Blood pressure was 153/86 mmHg and pulse rate was 91 beats/min. Cardiovascular and chest examination were unremarkable. Bilateral pitting oedema up to lower shin was seen. Abdominal examination revealed several purple striae. Spot urine for albumin was negative. Upon further enquiry, the patient revealed that she had been suffering from chronic low back pain and had been taking anti-inflammatory medication bought over-the-counter (OTC) from mainland China for pain control for the past few months. We went through what was the anti-inflammatory medicine and the ingredient was found to have Dexamethasone 0.75mg which she took daily. She, however, did not know of the nature of the medication and was unaware of its possible adverse effects. Baseline investigations which included complete blood picture (CBP), liver function test (LFT), renal function test (RFT), fasting sugar (FBS), fasting lipid (FL) and thyroid function test (TFT) were ordered and all came back as being normal. In view of the suspicion of Iatrogenic CS, blood test for cortisol level was checked. The result showed a low serum spot cortisol level of 37nmol/L (normal range 166 to 828nmol/L). She was subsequently referred to an Endocrine Specialist Clinic for further management and was advised not to stop the medication abruptly in view of the risk of adrenal insufficiency. She was then given a low dose short synacthen test to test her adrenal gland function which showed suboptimal response of 232nmol/L to 323nmol/L. She was thus diagnosed with Iatrogenic Cushing's with adrenal insufficiency and was started on hydrocortisone replacement. Her lower limb oedema has since resolved. DiscussionCauses of Cushion’s Syndrome (CS)Iatrogenic Cushing’s Syndrome remains the most common cause of CS, but its incidence is often underestimated as approximately 1% of the general population is using exogenous steroids. 1 Table 1 summarises different causes of CS.  Presentation Presentation of CS is often of multisystem and non-specific, which therefore poses a challenge to recognising and diagnosing in the primary care setting. Common signs include a moon face, central obesity, skin changes (facial plethora, easy bruising, purple striae) and proximal muscle weakness. Glucose intolerance, hypertension, osteopenia could also develop. Menstrual irregularity and signs of virilization may be present in female patients. 1 However, many of these signs can occur in individuals who are without CS, and not all CS patients present with these obvious clinical features. Therefore, primary care physicians should be on the alert and have a high index of suspicion to the signs indicative of CS. Family physicians should make a concerted effort to provide opportunistic education and advice against any occasion of drugs’ improper use without doctors’ assessment. Differential diagnosisLower limb oedema is a non-specific sign of Cushing’s Syndrome, and should be kept in mind when considering all possible differential diagnoses. Common causes of bilateral lower limb oedema are summarised in Table 2.  Amlodipine, one important antihypertensive from the calcium channel blocker (CCB) group, is a commonly used first-line antihypertensive in the primary care. CCB-related peripheral oedema is quite common in clinical practice and is caused by preferential arteriolar or precapillary dilation. A common pattern with CCB -related peripheral oedema is that the oedema is worse at the end of the day and improves after the patient has remained recumbent throughout the overnight hours. 2 It is usually dose dependent. In addition, the time from the administration of the drug to the onset of leg oedema often provides a helpful clue to a cause-effect relationship. In our case, CCB-induced oedema was less likely as the patient had been on Amlodipine for years and there was no recent change in dosage. In addition, the leg swelling was non-dependent in nature and was present throughout the day. The absence of orthopnoea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea and with a normal chest and cardiovascular examination did not suggest the presence of heart failure either. The patient also had no history or stigmata of chronic liver or renal disease, and the normal RFT, LFT and urine albumin reports made liver or renal disease related ankle oedema less likely. Associating signs suggestive of chronic venous insufficiency including varicose veins, lipodermatosclerosis or venous ulceration were not present. Myxoedema from hypothyroidism usually presents with non-pitting lower limb oedema with dry, thickened yellow to orange skin discoloration, but these were absent in our patient. 3 In summary, considering a history of prolonged corticosteroids use together with the presence of a moon face, truncal obesity, abdominal striae, and absence of symptoms or signs suggestive of other differential diagnoses, Iatrogenic CS was the most likely diagnosis.  Diagnosis and laboratory tests for suspected CS When a case of CS is suspected, a thorough drug history must first be taken to rule out Iatrogenic CS. The latest guideline from the International Endocrine Society suggests that after ruling out iatrogenic CS by a thorough drug history, one of the first-line screening tests, i.e. 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC), late-night salivary cortisol or overnight dexamethasone suppression test (ODST) should be performed. Random serum cortisol or ACTH level is not recommended as screening tests. 4 The Endocrine Society contends that there is no single-best test, and the choice of test varies across different countries and should be individualised for different patients. For instance, late-night salivary cortisol is not suitable for patients who have a variable sleep pattern e.g. shift workers, and the use of tobacco may cause a false positive result. UFC may be falsely elevated in patients with fluid intake >5L/day or reduced GFR, and its sensitivity and specificity are slightly lower than the other two tests. The result of ODST may be affected by a patient’s blood glucose level, exercise, poor sleep and concomitant use of enzyme inducers or inhibitors after the administration of dexamethasone. 5 Patients with a positive screening test should preferably always be referred to an endocrinologist for further confirmatory testing. For patients with a high pre-test probability, patients with clinical features suggestive of Cushing's syndrome and adrenal incidentaloma or suspected cyclic hypercortisolism but normal screening test, it is still recommended that it is better to refer them to an endocrinologist for further evaluation. 5 In summary, when CS is suspected in primary care:

It is worth mentioning that when a case of iatrogenic Cushing’s is suspected, caution must be taken to advise patients not to stop their steroids abruptly in order to avoid adrenal insufficiency. If high-dose steroid was to be stopped in the primary care level, it should be slowly titrated down with careful monitoring of withdrawal symptoms.

Wing-yee Siu, MBChB (CUHK)

Catherine XR Chen, LMCHK, FHKAM (Family Medicine), PhD (Med, HKU), MRCP (UK)

Ting-kong Poon, MBChB (CUHK), FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Correspondence to:Dr Wing-yee Siu, Room 807, Block S, Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

30 Gascoigne Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|