|

Sept 2020,Volume 42, No.3

|

Update Article

|

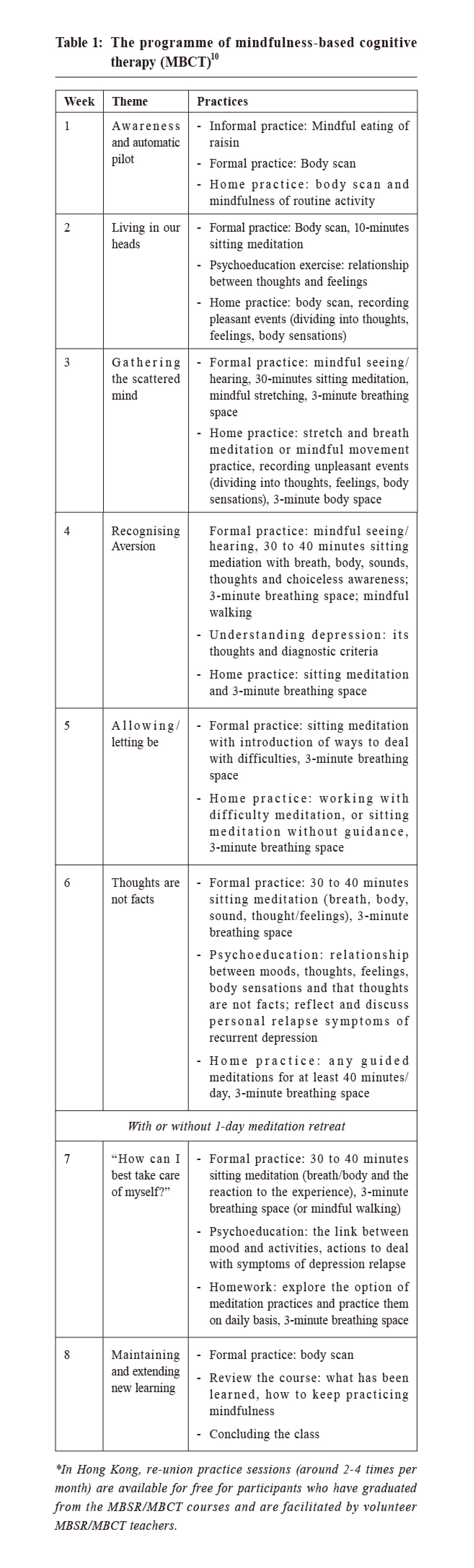

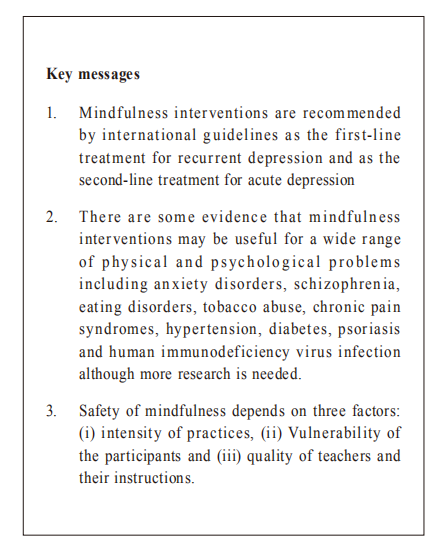

Mindfulness meditations: what family physicians can knowKam-pui Lee 李錦培,Samuel YS Wong 黃仰山 HK Pract 2020;42:51-57 SummaryRegular mindfulness practices have been shown to reduce stress and have multiple health benefits. An 8-week mindfulness intervention, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, is currently one of the first-line psychological treatments for recurrent depression. There is some evidence that mindfulness interventions may be useful for a wide range of physical and psychological problems including anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, tobacco abuse, chronic pain syndromes, hypertension, diabetes, psoriasis and human immunodeficiency virus infection although more research is needed. This narrative review also summarises the latest research findings on the safety of mindfulness interventions. 摘要定期靜觀修集已被證明可以減輕壓力,並具有多種健康益處。 為期8週的靜觀課程(靜觀認知治療)目前是複發性抑鬱症的一線心理治療之一。有證據表明,靜觀介入治療可能對許多生理和心理問題有療效,包括焦慮症,精神分裂症,飲食失調,吸煙,慢性疼痛綜合症,高血壓,糖尿病,牛皮癬和人類後天免疫力缺乏症病毒感染,儘管需要更多的研究 。 另外,這篇敘述性評論總結了有關靜觀介入治療安全性的最新研究結果。 IntroductionHong Kong, like many other developed parts of the world, is facing an aging population. Despite promotion of diet modification and regular exercise, chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases and psychiatric disorders remain increasingly prevalent here. 1 Clearly, besides all the advances in drug treatments, more specific and types of evidence-based lifestyle modifications are needed. Mindfulness meditation has been widely promoted by newspapers and magazines worldwide, to be one of such options. Research during the past decade has found that regular mindfulness meditation can reduce stress, and enhance concentration, memory, self-compassion and empathy. 2-4 Brain scans in participants after a 8-week mindfulness programme have found an increase in activities and/or in volume in brain structures that facilitates emotion regulation and executive functions (prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, insula and hippocampus) and decrease in activities in the amygdala, which is implicated in the anxious or ‘fight or flight’ response. 5 Recent research even suggests that regular mindfulness practice can enhance telomerase activities (which maintain the length of telomeres at cellular level). 6 Furthermore, it is one of the most ‘mobile’ lifestyle changes, compared to the extra expenditure or equipment which is often needed to maintain a new diet or exercise routine. Meditation, once learned, can be conducted anywhere and anytime at the convenience of the meditator. Despite its being originated from Eastern Buddhism, the mindfulness practices were made secular by Western scientists. In the 1970s, Jon Kabat-Zinn developed a group-based eight-week programme called “mindfulness-based stress reduction programme” (MBSR), which taught various mindfulness practices, including mindful eating, body scan, mindfulness walking, awareness of the breath and mindful yoga. Since then, MBSR was modified to treat various physical and mental diseases. As more people are learning mindfulness meditation, family physicians will need to understand how mindfulness practices can potentially affect disease processes or be used in primary care. This review aims to provide an overview of the latest scientific evidence of mindfulness interventions in relation to the many common problems and situations encountered in primary care in Hong Kong. Definition of mindfulnessAlthough many definitions exist, one of the most commonly used definitions is ‘the awareness that arises from paying attention on purpose, in the present moment non-judgmentally in the service of self-understanding, wisdom, and compassion’. 7 Mindfulness, like many other innate abilities such as running or reading, can be systematically trained. During the 8-week programmes, this non-judgemental awareness is trained by intentionally and repeatedly focus back on the meditation object(s) (often include breath, body sensation, sound and thoughts) in the present moment. 10 Participants are given home practices so that they are encouraged to meditate regularly during and after the 8-week programme. A sample of a 8-week programme can be found in Table 1.

Mindfulness and psychiatric illnessUnipolar depressionPatients with recurrent depression (i.e. suffered from 3 or more depressive episodes in the past) have a very high risk of future depressive episodes. Lifelong maintenance drug treatment is often recommended to prevent relapse, but patients often have poor drug compliance and often prefer non-drug treatments. 8,9 An 8-week mindfulness programme called ‘Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy’(MBCT) was developed to prevent relapse in people with recurrent depression. 10 MBCT, similar to MBSR, consists of eight weekly 2-hour classes, and participants are asked to do mindfulness exercises daily (which last for 40-50 minutes per day) during and after the 8-week programme. 10 While patients with recurrent depression often have self-defeating thoughts with minimal trigger (e.g. a normal mood swing), MBCT taught participants to observe the temporary nature of these thoughts, feelings and body sensations and decentre from them. 10 In an individual data meta-analysis, patients who received MBCT had a lower relapse rate than patients who received no MBCT (hazard ratio (HR) 0.69; 95%CI: 0.58- 0.82; I 2 = 1.7%), who received other active treatments (HR 0.79; 95%CI: 0.64-0.97; I 2 = 0%) and who received antidepressant treatments (HR 0.77; 95%CI: 0.50-0.98; I 2 = 0%).11 MBCT is currently advised by the NICE guideline for patients with recurrent depression but who are currently in remission.12 In contrast to recurrent depression, relatively fewer studies have investigated the effect of MBCT in patients with acute depression because mindfulness meditations (e.g. concentrating on breath and body sensations while observing difficult feelings and thoughts) were predicted to be difficult for these patients. MBCT is currently regarded as a second-line psychological treatment for patients with acute depression in the Canadian guideline. 13 A meta-analysis, which included 13 studies and was published in 2019, found that MBCT was more effective than non-specific control (Cohen’s standardised effect d = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.47, 0.96; I 2 = 50.4%) and was not different from active control (Cohen’s standardised effect d = 0.002, 95%CI: −0.43 0.44; I2 = 65.34) in reducing depressive symptoms in patients with acute depression.14 Although the current evidence does suggest MBCT can help patients with acute depression, it was limited by the lack of long-term follow-up period and that high-quality trials tend to have a smaller effect size. 14 Anxiety disordersThe results for mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) to treat anxiety disorders were mixed . Hoffmann et al. conducted a meta-analysis, including heterogenous samples of patients with generalised anxiety disorder, depression, cancer patients, and other patients with medical or psychiatric issues, and found that MBIs was moderately effective in reducing anxiety symptoms in these patients. 15 Similarly, Vøllestad et al. conducted another meta-analysis which investigated the effect of MBIs and other acceptance -based interventions and found a robust reduction in anxiety symptoms. 16 However, Strauss et al. conducted a meta-analysis in 2014 and found that MBIs were not effective in reducing anxiety symptoms in patients currently diagnosed to have depressive or anxiety disorders. 17 In Hong Kong, Wong et al. conducted a randomised control trial involving 182 patients with generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), and found that a modified MBCT was more effective than usual care and was not different from psycho-education based on cognitive behaviour therapy. 18 In short, although some promising evidence suggests using MBIs to treat anxiety disorders, more studies are needed. Other psychiatric disordersSimon et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis and suggest that MBIs were also effective in treating schizophrenia, eating disorders, and tobacco abuse. 19 Furthermore, specific MBIs are being developed for various psychiatric disorders, for example, MyMind program for patients with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance and alcohol abuse disorders. 20,21 Mindfulness and physical illnessChronic painBesides the actual sensation of pain, patients with chronic pain often magnify the suffering by rumination and automatic catastrophic thoughts about the pain and its associated consequences (e.g. loss of sleep or loss of function). 22 Rather than automatically reacting to pain, mindfulness meditations train patients to allow, observe and de-centre from the pain sensation and the associated secondary reaction, and therefore lessen the suffering.23 Brain functional studies have confirmed that mindfulness training can produce changes in multiple parts of the brain involved in cognitive and emotional evaluation of pain.24 Recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials found that mindfulness interventions had a small effect size to reduce pain and could improve physical and mental quality of life in patients with chronic pain; however, the current evidence was limited by high heterogeneity of results from different trials and a relative lack of high quality studies.25 Similarly, although Anheyer et al. published another meta-analysis and found that MBSR was effective in reducing chronic low back pain in the short term, there remained a lack of trials utilising an active control group.26 Chronic diseasesBecause mindfulness training can reduce stress and enhance self-care behaviour, it may improve the control of and prevent complications from chronic diseases. 27,28 Pascoe et al. conducted a meta-analysis and found that meditation (including mindfulness meditations, mindfulness retreats and other practices like Transcendental meditation) could reduce systolic blood pressure by 5.37mmHg (95%CI: 2.5-8.25mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure by 2.96mmHg (95%CI: 0.85-5.07mmHg). 29 However, it was not known if mindfulness meditations alone could reduce blood pressure. An older meta-analysis in 2014 investigating effect of mindfulness interventions on blood pressure found that there were only 4 relevant studies and results were heterogeneous (I 2 = 89%); therefore no definite conclusion could be drawn. 30 Mindfulness was also found to reduce diabetic stress and enhance self-care behaviour in patients with diabetes mellitus. 31 Although there is currently insufficient conclusive evidence to suggest whether mindfulness interventions can improve diabetic control (i.e. by glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c)), few recent randomised controlled trials have found that mindfulness training could reduce blood glucose and HbA1c. 32 OthersMindfulness interventions were suggested to be adjuvant treatments in other physical diseases that were exacerbated by stress. For example, mindfulness exercises may reduce symptoms and enhance quality of life in patients with psoriasis 33; similarly, MBIs may reduce depressive symptoms and increase CD4+ counts in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. 34 Mindfulness and healthcare professionalsBurnout, which is a state of emotional and physical exhaustion, is prevalent among medical students and doctors. 35 In Hong Kong, around one-third of doctors working in the public sector suffered from burnout.36 Besides causing personal suffering, burnout is associated with suicidal ideation even after controlling for the presence of depression, professional misconduct and can adversely impact on patient care. 35, 37-39 Evidence-based interventions are needed. 39 MBIs can be a viable option because regular mindfulness practices can reduce stress and enhance self-care . Although recent meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials had confirmed that MBIs had a moderate effect on stress reduction in healthcare professionals, individual trials were small in size and more studies were needed. 40,41 Other studies have suggested that clinicians with higher level of mindfulness were more willing to communicate with their patients and had more satisfied patients; it remains unclear if providing MBIs to clinicians can lead to improvements in patients’ outcomes. 42 Safety of mindfulness practicesThere is detailed guidance and discussion on safety of mindfulness practices on the Oxford Mindfulness Centre webpage (refer: https://oxfordmindfulness.org/ news/is-mindfulness-safe/). In short, the safety of mindfulness practices depends on three factors:

1. Intensity of practiceGenerally, the risk of adverse events correlates with the intensity of practice. For example, there is no evidence of harm in low intensity practices such as bringing awareness to the taste of food or to the sensation of walking; however, there has been isolated reports of psychotic episodes and suicides in newspapers after prolonged silent meditation retreats (available on https://www.pennlive.com/ news/2017/06/york_county_suicide_megan_vogt. html).

2. Vulnerability of the participantsWhile participants with particular characteristics (e.g. past history of psychological trauma) may be more prone to experience adverse effects during psychotherapies, it remains unclear who will not benefit or even sustain harm from MBIs. Paradoxically, patients with past psychological trauma may benefit most from MBIs. 11 3. Quality of teachers and their instructionsBodily and emotional discomfort often arises during meditations. Skilful advice and guidance are needed to help participants to learn new ways to deal with these difficulties and this can lead to substantial personal growth. Despite there being no licensing system for MBI teachers in Hong Kong, it is clear that systematic training is required. For example, to become a MBCT teacher, he or she will need to (i) have daily mindfulness practice, (ii) complete a 8-week MBCT or MBSR program as a participant, (iii) participate in the 1-year foundation course for MBCT teacher or a 1-week retreat organised by the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, and (iv) yearly silent retreat(s). He or she then can teach MBCT under supervision and may apply for certification from the Oxford Mindfulness Centre. 43 A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials conducted by our team found that, when conducted under the guidance of qualified teachers, there was no increase in the number of adverse events in patients receiving the 8-week MBSR or MBCT program (which are considered as ‘moderate intensity training’) compared to patients assigned to the control groups. 44 In the authors’ experience, harm is uncommon and is often associated with difficult thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations during meditations. However, by learning to handle these difficulties skilfully, these practices can lead to substantial personal growth. This is now discussed in the manuscript. Mindfulness development and practices in Hong KongMBIs are increasingly used clinically in countries where the use of MBIs are recommended by guidelines or covered by insurance. For instance, five centres in the United Kingdom had provided MBCT to more than 1,500 patients with depression and found encouraging results. 45 Similarly, around 10% of the United State workforce had regular mindfulness practices. 46 In contrast, there is inadequate data on the prevalence of the use of MBIs in Hong Kong and there is currently no local guideline to suggest clinical indications for MBIs. The use of MBIs often depends on the expertise of the doctors or therapists and the background of the patients because MBIs are often self-financed in Hong Kong. The CUHK Thomas Jing Centre of mindfulness research and training are co-operating with Oxford centre of mindfulness to offer a 1-year teacher training program for healthcare professionals who wish to use MBCT to help patients. Ways to experience mindfulness meditationsDoctors who would like to experience mindfulness can:

ConclusionAlthough mostly used to treat depression, it is foreseeable that mindfulness-based interventions will soon be applied to a range of physical and psychological illnesses. Therefore, family physicians should know the basics and keep up-to-date with the latest evidence of various mindfulness-based interventions.

Kam-pui Lee, MBBS (HK), MSc (Oxon), FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Samuel YS Wong, MD (U. of Toronto), MPH (Johns Hopkins), FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Correspondence to:Kam-pui Lee, Room 402, School of Public Health, Prince of

Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|