|

Sept 2020,Volume 42, No.3

|

Update Article

|

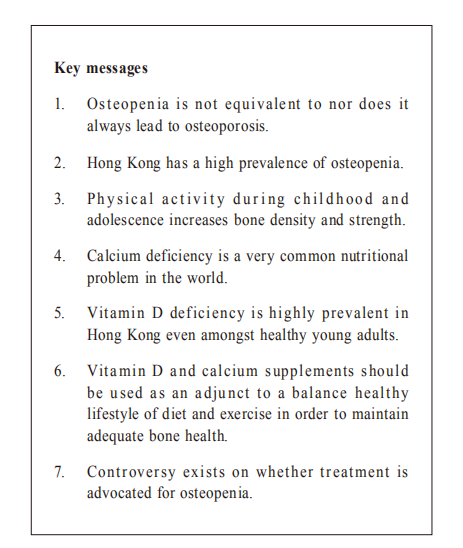

Review of OsteopeniaKathy KL Tsim 詹觀蘭 HK Pract 2020;42:62-69 SummaryIn a world with an increasing aged population, osteoporosis has become a recognised global health problem with its substantial bone-associated morbidities, mortality and health-care costs. The stage before osteoporosis occurs is called osteopenia. Having osteopenia does not necessarily proceed to osteoporosis. However, steps can be taken to improve a person’s bone health and to reduce their osteoporotic risk. This article will share with the readers the current knowledge , controversies and management of osteopenia, osteoporosis and osteosarcopenia. 摘要伴隨人口老化,骨質疏鬆引發大量相關骨病的發病率,以致增加了死亡率和醫療成本,骨質疏鬆已經被公認為全球的健康問題。骨質疏鬆的前期為缺乏骨質,然而通過治療,改善骨質健康,可以減低發展為骨質疏鬆的危險。本文作者與讀者分享了,有關骨質缺乏和骨質疏鬆和骨肌肉減少症候群(osteosarcopenia)的討論意見,和最新知識及治療方法。 IntroductionLosing bone density is a normal part of ageing and is person specific. The stage preceding osteoporosis is known as osteopenia. This condition occurs because the osteoid synthesis is not sufficient to overcome osteoid lysis. Osteopenia is having a lower bone density than the average for the patient’s age group, but not low enough to be classified as osteoporosis. The UK Royal Osteoporosis Society states that having a low bone density can increase a person’s fracture risk, but is not necessarily an imminent event. Osteopenia is one of many risk factors for sustaining fractures. Whether actual medical treatment is deemed necessary depends on the outcome of a person’s fracture risk assessment. 1 Impact of osteopenia and osteoporosis in societyAccording to a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis, it was found that the pooled prevalence of osteoporosis in people aged 50 years and older in China was more than twice the pooled prevalence identified in 2006. 2 This figure has increased over the past 12 years, affecting more than one-third of the people aged 50 years and older. No specific prevalence data is currently available for Hong Kong. However, epidemiological studies has shown that the incidence of hip fracture has increased by 300% from 1960s to 1990s. Fortunately this has since stabilised from 2001- 2006. 3 Despite the stabilisation of hip fracture rates, fractures remain a major burden on health services and society. The prevalence of vertebral fractures in men and women between the ages of 70-79 are comparable to those in American Caucasians. Osteoporosis is not officially documented as a national health priority in Hong Kong. 4Nevertheless, osteoporosis is a major and increasingly important public health issue in our locality. Although the incidence of age-adjusted hip fractures seems to be decreasing over time when compared to Caucasians, Hong Kong men and women still have a high prevalence of osteoporosis and a lower Bone Mineral Density (BMD) (osteopenia) rate. Prevention and control measures have become important in a society which is growing older and the care burden from bone fractures are forever increasing. Recently, there has been the recognition of osteosarcopenia, a syndrome seen in frail, elderly patients as having a higher risk of falls, fractures, disability and frailty. This new syndrome, consists of a combination low Bone Mineral Density (BMD T-score <–1 standard deviation) and sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is defined as a “syndrome characterised by progressive and generalised loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, with a risk of adverse outcomes such as physical disability, poor quality of life and high mortality” 5 which can be detected with the use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). In other words, osteosarcopenia has been defined as the presence of sarcopenia and osteopenia or osteoporosis.5 Interestingly studies of patients with type-1 diabetes mellitus have demonstrated an association between BMD and microvascular complications. 6,7,8 Most studies reporting an increased prevalence of fractures in these patients despite an apparently increased bone mineral density. Some advocate that fragility / low-impact fractures may be a “neglected” complication of diabetes. Detection of osteopeniaUnlike osteoporosis (even in the absence of fractures) which can result in chronic pain affecting a person’s daily activities, osteopenia is asymptomatic. 2 This means that osteopenia can go undetected for years before bone loss is so severe that osteoporosis develops. When osteopenia does cause symptoms, it may result in localised bone pain and /or low-impact fractures. Low-impact fractures can often be the result of falls from one’s own standing height or lower. They can happen during normal daily activities, e.g. from getting out of a chair or stepping off of a curb. Interestingly, sometimes bone fractures can even occur without noticeable pain. Osteopenia may be suspected by findings on plain film X-ray of increased bone radiolucency which can be seen as a decreased cortical thickness and loss of bony trabeculae. However, the standard test for measuring the density of bone and detecting osteopenia is a bone density test, either via a CT scan of the lumbar spine (quantitative computed tomography or QCT) 9,10 or, more commonly, by DEXA (dual energy X-ray absorption) bone density test. Ultrasound of the bones of the heel, leg, kneecap, or other areas are sometimes used commercially. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has established DEXA as the best densitometric technique for assessing BMD ( Bone mineral density ) in postmenopausal women and based the definitions of osteopenia and osteoporosis on its results. It is the gold standard imaging technique for the assessment of BMD. It not only allows for the accurate diagnosis of osteoporosis, fracture prediction, but also as a monitoring tool for patients undergoing treatment. DEXA scanner uses beams of very low-energy radiation to determine the density of bone. The amount of radiation is low: about one-tenth of a chest X-ray. There are significant differences in the performance of different techniques to predict fractures at different skeletal sites. The bone density test provides a numerical rating of the density of the bones measured. Bones that are often tested in this manner include the lumbar spine, the femur bone of the hip, and the forearm bone. DEXA scores are reported as "T-scores" and "Z-scores". 11 "T-scores" and "Z-scores"The T-score is a comparison of a person's bone density with that of a healthy 30-year-old of the same sex. The Z-score is a comparison of a person's bone density with that of an average person of the same age and sex. Lower scores (more negative) mean lower bone density.

Multiplying the T-score by 10% gives a rough estimate of how much bone density has been lost. Although the reference standard for the description of osteoporosis is BMD at the femoral neck, other central sites (e.g. lumbar spine, total hip) can be used for diagnosis in clinical practice. T-scores should be reserved for diagnostic use in postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or more. 12 With other measurement techniques, and other populations, values should be expressed as Z-scores, other units of measurement or preferably in units of fracture risk. In premenopausal women, a low Z-score (below -2.0) indicates that bone density is lower than expected and should trigger a search for an underlying cause. Re-screening, for women with normal bone density or mild osteopenia, is advocated to be at an interval of 15 years and 5 years for women with moderate osteopenia, and yearly for women with advanced osteopenia. 13 It was found that 10% of women with moderate osteopenia at baseline developed osteoporosis within 5 years. For those with advanced osteopenia at the start, about 10% had developed osteoporosis within a year, suggesting more aggressive yearly screening to be more appropriate. This is assumed that no other risk factors has arisen since their last screening. Meanwhile, a prediction tool, the Osteoporosis Preclinical Assessment Tool (OPAT), has been developed to assess the osteopenia risk of women aged 40-55 years by a group of Taiwanese researchers in 2010. This tool collected the age, menopausal status, weight, and serum total Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level of patients in order to predict their osteopenia risk. It acts as a simple and accurate prescreening tool for identifying premenopausal and early postmenopausal women without the need for bone mineral density values unlike the most widely used FRAX@ on-line questionnaire. 14 Just as the authors has indicated more validation of this tool is needed; but hopefully this will be available as a tool that physicians can access soon in the near future. What are causes and risk factors for osteopenia?Normal bone development with achievement of peak bone mass is influenced by several factors: i.e. genetics 15,16,17, nutritional status, hormones, exercise18, and other physical factors. Hence possible risk factors for osteopenia include the following 18:

It is important to differentiate other causes of osteopenia, for example, osteomalacia, primary hyperparathyroidism, and malignant diseases such as myeloma, since these bone diseases have a different natural history, pathophysiology, and treatment. What can patients with osteopenia do to improve their bone health?As family physicians there are some simple but very important things that we can advise our patients with osteopenia to ensure better bone health. The following practices should be encouraged 18:

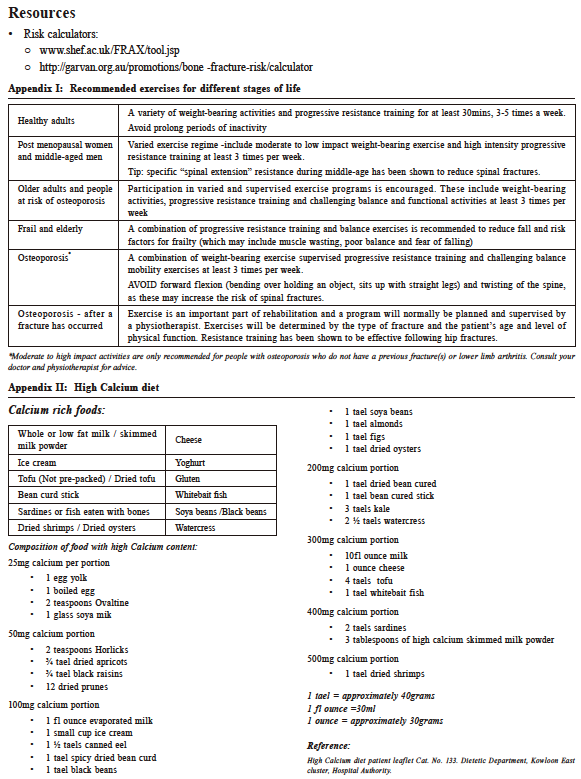

Exercise is important to prevent osteopenia and henceforth osteoporosis. Physical activities during childhood and adolescence increase bone density and strength. Children who exercise are likely to reach a higher peak bone density (maximum strength and solidness). Peak bone density is reached during mid- to late- 20s. 14 People who reach a higher bone density are less likely to develop osteopenia, and hence osteoporosis. Physical activity throughout life is also important in maintaining adequate bone mass and bone health. Even in older adults, strength training has a significant positive influence on BMD with osteoporosis or osteopenia. 19 Even a general-purpose exercise program with emphasis on bone density has a positive impact in osteopenic women. 20 Exercise can improve not only a person’s strength and endurance, but it can also reduce back pain, and improve lipid levels. However, it is recommended not to rely on exercise alone but rather to combine strength training, diet and supplements to ensure good bone health. Types of exercises for bone health 21,22There are two types of important exercises that are important for building and maintaining bone density : weight-bearing and muscle- strengthening exercises.

Note:

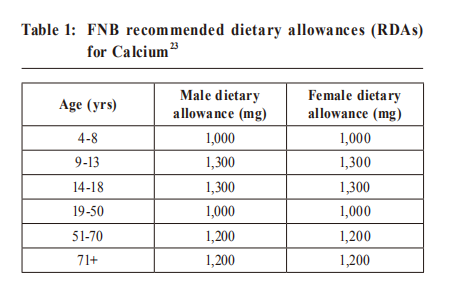

The US Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) has established Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) which are the reference for average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%-98%) healthy individuals for the amounts of calcium required for bone health. They are listed in Table 1 in milligrams (mg) per day.

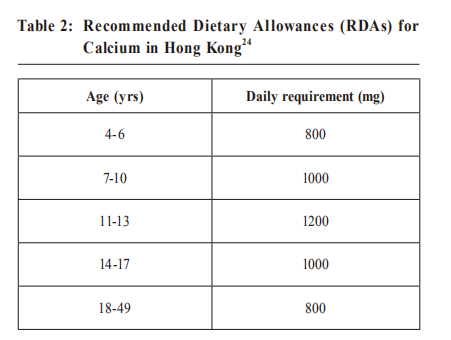

Recommended intake as seen is different in the US as compare to our locality.

Reference: The Chinese Dietary reference intake (2013) The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organisation ( WHO ) recommendations for calcium intake is between 1000 and 1300 mg/ day and nearly all Asian countries fall far below this general recommended level. The median dietary calcium intake for the adult Asian population is approximately 450 mg/day, with a potential detrimental impact on bone health in the region. 25,26,27 This is further supported by data from the 2015 China Nutritional Transition Cohort Study (CNTS) showing that calcium deficiency is a very common nutritional problem in the world but especially so in China. 27 Since January 2010 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) statement on calcium, vitamin D and bone health is that adequate calcium and vitamin D should be part of a healthy diet, along with physical activity with the possible beneficial effect of reducing osteoporosis risk in later life. Calcium supplementationThe two main forms of calcium in supplements are carbonate and citrate. Calcium carbonate is more commonly available and is both inexpensive and convenient. Due to its dependence on stomach acid for absorption, calcium carbonate is absorbed most efficiently when taken with food, whereas calcium citrate is absorbed equally well when taken with or without food. 23 Calcium citrate is useful for people with achlorhydria, inflammatory bowel disease, or absorption disorders. Other calcium forms in supplements or fortified foods include gluconate, lactate, and phosphate. Calcium supplements contain varying amounts of elemental calcium. For example, calcium carbonate is 40% calcium by weight, whereas calcium citrate is 21% calcium. Fortunately, elemental calcium is listed in the bottle’s supplement facts panel, so consumers do not need to calculate. Foods that affect Calcium absorption

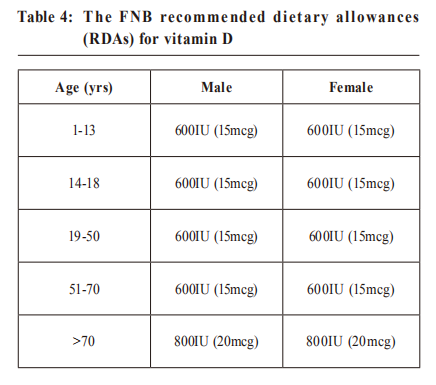

Absorption is highest in doses ≤500 mg per dosing. So it is best to split a 1,000 mg/day of calcium supplement tablet into 500 mg at two separate times during the day. (C) Vitamin DLocal studies have found that vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent even in healthy young adults. 28 This is a surprise finding in such an affluent city like Hong Kong where there is no lack of available sunshine or food. For most people, 5 to 15 minutes of casual sun exposure of the hands, face and arms 2 to 3 times a week during the summer months is sufficient to keep the vitamin D level high. People with darker skin need a longer sun exposure time. 29 It has been reported that in Hong Kong, the means of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D (calcifediol) levels in different age groups were lower when compared with similar age groups from Japan, Thailand, Taiwan, Vietnam as well as from most countries in North America. 30 Very few foods in nature contain vitamin D. The flesh of fatty fish (such as salmon, tuna, and mackerel) and fish liver oils are among the best sources. Small amounts of vitamin D are found in beef liver, cheese, and egg yolks. Some mushrooms provide vitamin D2 in variable amounts.

Vitamin D aids the absorption of calcium and hence is usually given together. In fact a modest reduction in hip and other fractures can be seen when low dose vitamin D (about 10 mcg daily) was given with a calcium supplement as compare to vitamin D given alone irrespective of dose. However, there is a controversial risk of nephrolithiasis with calcium / vitamin D supplements. Meta-analyses reported an increased risk of renal stones with the combination of vitamin D and calcium though not for vitamin D supplementation itself. 31 There is also a concern that excessive calcium supplementation may increase myocardial infarction risk. This risk has not been seen with dietary calcium, only with supplements. 32 Hence vitamin D and calcium supplements should be used as an adjunct to a balance healthy lifestyle of diet and exercise. As recommended by the Osteoporosis Australia, a supplement of no more than 500-600mg of Calcium per day should be adequate. 18 Aim for a minimum of 1000 mg calcium per day by diet to maintain bone density. This is of course if secondary causes of osteopenia/ osteoporosis have been ruled out. To treat or not to treatWhether pharmacological treatment is deemed necessary if osteopenia (without fracture) is detected is still under heated debate. 33 While the most effective anti-resorptive treatment today have a NNT (Numbers needed to treat) value of around 13-15 for spine fracture prevention, the NNT in osteopenia patients are 8-10 times higher. One important fact is that most patients with osteopenia are younger. 32 Studies on bisphosphonates, have also noted that clinical fractures were only significantly reduced in patients with T-scores < −2.5 (osteoporosis range). However the controversy is that morphometric fractures have in the same study been shown to be reduced even in patients with a T-score > −2.5. 34 Health care resources and health economics also plays a role in this debate. One study found that at 50 years, only calcium and vitamin D was cost-effective economically, whereas at 70 years, bisphosphonates and raloxifene were cost-effective. 3 Hence most guidelines for osteopenic patients therefore primarily focus on lifestyle changes , nutritional improvements, calcium and vitamin D supplementation , exercise regimens as primary interventions. Pharmacological treatment depends on the outcome of a person’s fracture risk assessment. There are various tools which are widely available for the family doctor to help with this decision making. The most widely available is the online FRAX® tool which uses a range of 12 risk factors to predict a person's risk of fracture because of weak bones. This self-assessment tool gives a 10-year probability of a fracture in the spine, hip, shoulder or wrist for people aged between 40 and 90. It integrates the risks associated with clinical risk factors as well as bone mineral density (BMD) at the femoral neck. If the bone mineral density is unavailable then the Fracture risk calculator developed by the Garvan Institute of Medical research can be used.

So should family doctors screen for osteopenia? There are many considerations but ultimately this is a very person specific decision. A patient agreed management plan is the best option to optimise the health of the person in front of us.

Kathy KL Tsim, MBChB (Glasgow), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family

Medicine)

Correspondence to:Dr Kathy KL Tsim, Tseung Kwan O (Po Ning Road)

General

Out-patient Clinic, G/F, 28 Po Ning Road, Tseung Kwan O,

Hong Kong SAR.

References:

|

|