|

December 2021,Volume 43, No.4

|

Original Article

|

Facilitators and barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women in Hong Kong: A qualitative studyChui-ying Fong 方翠瑩,Lai-shan Chu 朱麗珊,Wan Luk 陸雲 HK Pract 2021;43:105-118 Summary

Objective:

To explore the attitudes and barriers to

cervical cancer screen among ethnic minority women in

Hong Kong.

Communiity-based cervical caner screening education and services can ameliorate the language, practical and emotional barriers. Keywords: facilitators, barriers, cervical cancer screening, ethnic minority, qualitative study 摘要

目標:

探討在港少數族裔婦女對子宮頸癌篩查的態度和障礙。

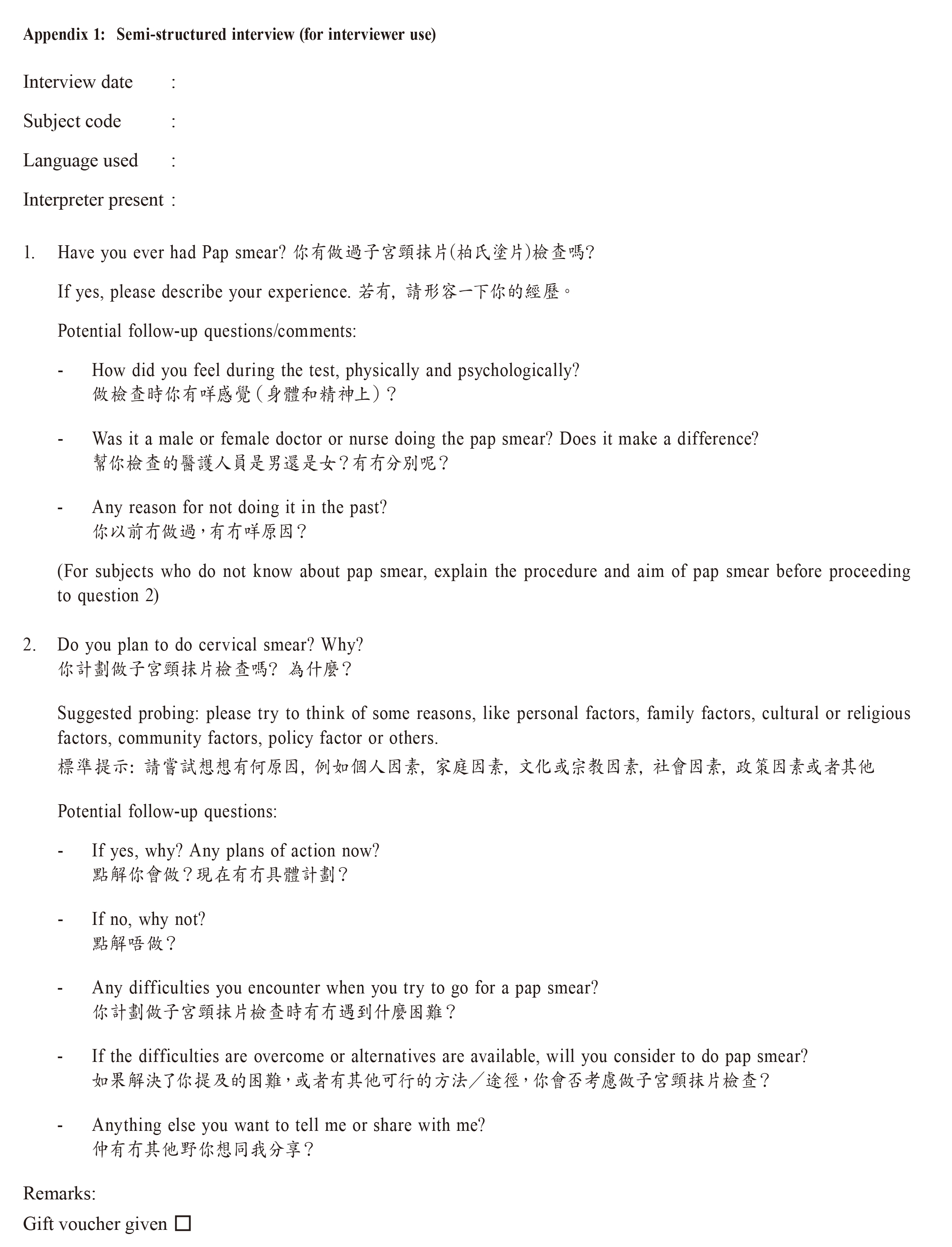

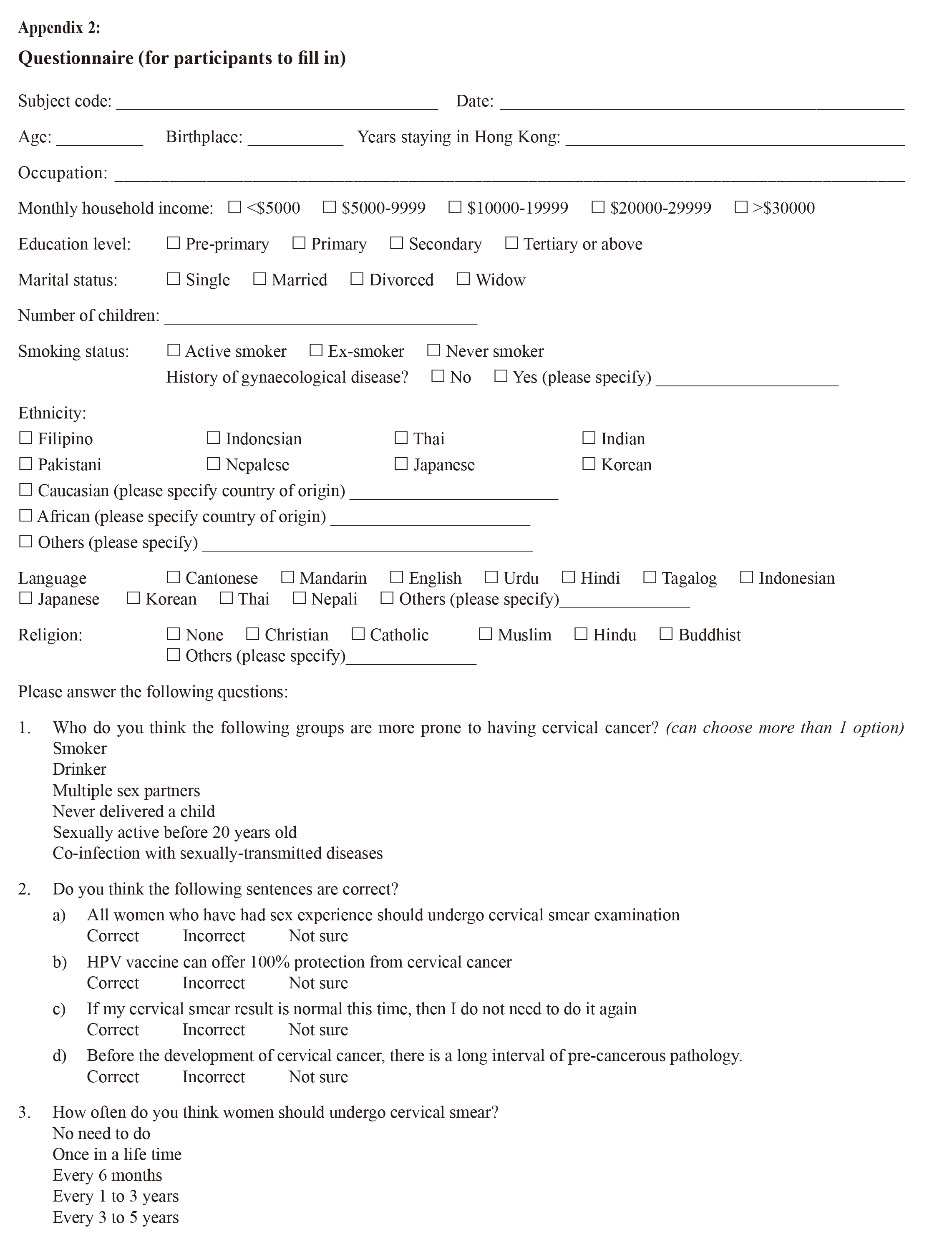

關鍵字: 推廣方法,障礙,子宮頸癌篩查,少數族裔,定性研究 IntroductionIn Hong Kong (HK), ethnic minorities (EM) refer to persons who report themselves as of non-Chinese ethnicity in the population census. 1 They constitute 8% of HK’s population and its number has increased by more than 70% over 10 years to 584,383 in 2016. The three largest ethnic groups were the Filipino (31.5%), Indonesian (26.2%) and South Asians (14.5%), which include Indians, Nepalese, Bangladeshis and Sri-Lankans. More than half of the EM group (320,790 persons, 54.9%) are women employed as domestic helpers. Malignant tumours is the top leading cause of death in HK.2 Among all local women, cervical cancer (CC) was the 7th commonest cancer in 2016, and the 9th leading cancer mortality in 2017.3 Globally, CC is the 4th commonest cancer in women, with higher disease burden in less developed regions such as Africa, India, and South-east Asia.4 Low-income local Chinese, new immigrants from Mainland China and EM women were found to have a significantly higher prevalence of cervical cancer screening (CCS) abnormalities.5 Among them, being South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Nepalese and Bangledeshi) and South-east Asian (Indonesian, Filipino and Thai) had 6- to 11-fold increased risk of abnormal CCS compared with the local HK Chinese population. Cervical cancer screening is an effective method to detect pre-cancerous lesions and prevent cervical cancer. Cytologic screening is the most important factor to reduce the risk of progression from herpes papilloma virus ( HPV) infection to invasive CC.6 However, CCS uptake remains low globally, especially among EM in many populations.7-9 In HK, 60.5% of women aged 25 to 64 have ever screened for CC. Most asymptomatic women (55%) had their Pap smear (PS) performed at private clinics and 76.7% of them had their last PS within the preceding 36 months.10 The regular PS uptake (PS done within the last 3 years) was reported to be 63.9% among Chinese women in HK.11 On the contrary, 61.2% of EM women have never had a PS.5 The ever-screened rate among South Asians was significantly lower than the general public (36% VS 48%) in HK.1 Low socioeconomic status, low education level, low health literacy, older age, language barriers, not having a female provider, being an immigrant, short duration of residence and lower perceived risk of CC have been demonstrated to be associated with non-attendance for PS among the EM population.5,8,13-15 The cost of attending PS, including transportation, the service itself and taking time off work, may be unaffordable for some EM women. Low level of acculturation (which encompassed language, ethnic identity, friendship choices, duration of residence, etc.) was suggested to affect uptake of screening.13 A review of foreign female domestic workers suggested that the governments of both labour-sending as well as host countries should have policies adjusted to facilitate the workers’ health.16 Cognitive, emotional and procedural-related factors have been commonly reported as barriers to PS in different populations8,11,15,17-20, whereas some factors are ethnicity-specific. Lack of usual sources of care, practical issues, language barriers, fatalistic attitude and peer recommendations have mainly been observed in Asian groups.13,18-20 Family history of cancer and having a positive relationship with doctors were facilitators identified only in the black populations13. Lack of a national CCS programme was highlighted to cause low screening rates in Nepal and the United Arab Emirates.21,22 The EM groups in overseas studies included African American, Caribbean, Chinese American, Korean, East European, Hispanic women, Indian, Pakistani, Somali, Chinese Australian etc.7,8,13-15,17,19 They compared the CCS uptake rate and screening behaviour with reference to their Caucasian majority. Therefore, results from overseas studies may not be generalisable to Hong Kong, where Chinese are the majority and other Asians are the minority. A previous study focused on Filipino domestic helpers in HK.23 Nowadays, the EM workers in HK can be from Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, India and even Caucasian countries and their barriers to regular cervical smear in HK have not been studied locally. In order to enhance the services and policy for promoting regular CCS in the EM women’s social context, family physicians play an important role in promoting and performing CCS for patients in the primary care setting. The aim of the current study is to explore the facilitators and barriers to cervical cancer screening among EM women in HK. By gaining a better understanding, culture-specific measures can be designed by both labour-sending countries and HK governments in order that cervical cancer screening will be improved and the health burden of cancer cases will be lessened. MethodologyThis study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Kowloon West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (Reference number KW/FR-18-089(125-05)). ProcedureThis study was a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews. Open-ended questions were asked to explore the multi-level factors in depth, especially in a culturally diverse study population. Individual face-to-face interviews (Appendix 1) were conducted in community settings, including churches, non-profit community centers and an international school. Subjects’ personal experiences on Pap smear was first inquired. Afterwards, their reasons for attending or not attending CCS were explored in greater detail. All the interviews were conducted by the first author, a female doctor who received specialist training in family medicine. The stury subjects’ baseline demographic data were collected (Appendix 2). Their idea on CC was assessed by a set of multiple-choice questions which was designed with reference to a questionnaire used in another local study11 and a local CCS recommendation document.24 The results were used to facilitate discussion if they had any misconceptions on CCS and CC. The inclusion criteria were non-Chinese women aged 25-64 years who ever had sexual experience and with legal residency in HK. Subjects with a present or past history of cervical cancer, had hysterectomy, mentally incapacitated and persons with active and unstable psychiatric illness were excluded. ParticipantsSubjects were mostly recruited by purposive sampling between October 2018 and February 2019. To gain a broader range of views, a diverse spread of EM women were recruited to sample different ethnicities, occupations, ages and educational levels. Filipino and Indonesian churches were first approached for subject recruitment since most Filipinos and some Indonesians in Hong Kong are Christians and churches are common gathering places on week-ends. Non-profit community centres that serve Indonesian domestic helpers and South-asian groups, mainly Indians, Pakistanis and Nepalese, were contacted for collaboration. Teachers from an international school were invited to participate in the study to enhance the diversity of ethnicities and socio-economic status of the subject pool. To increase sampling, we used a snowballing technique and invited subjects to introduce other subjects according to our targeted- subject characteristics. Women were either invited by the organisation co-ordinators to join the study or those who responded to the first author after a face-to-face or saw our email description of the study. Subject recruitment was continued until data saturation. The target number was reached at 30 interviewees, which was consistent with the sample size recommended in literature.25 A reward of $50 gift voucher was offered to every participant. The information sheet and a written consent form were translated into Hindi, Urdu, Indonesian, Japanese and Korean for corresponding EM subjects. Subjects who could not communicate effectively in Cantonese, English or Mandarin were accompanied by an interpreter during the interviews with their consent. All the interpreters were arranged by the Non-government Organisations (NGOs). They were acquaintances of the participants to increase the participants’ comfort and confidence. They were either EM women themselves or were of EM descent and were therefore fluent in the EM languages to enhance the accuracy of the translation. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed per verbatim. If an interpreter was present, the interpreted response was transcribed. The transcripts were returned to participants for comment if they consented and were reachable. Moreover, two of the authors checked the content validity between audio records and transcripts. Data CollectionWe used a semi-structured questionnaire to guide the interviews. Field notes were made during the interviews. Each interview session lasted 30-50 minutes, including introduction of the research, informed consent, interview, filling in questionnaire and performing the quiz. There were no repeat interviews. Transcripts were returned to some participants for comments and checking if the participants consented and were reachable. AnalysisThe transcript was analysed manually using thematic analysis26 by the first and second authors. After familiarisation with the data, a conceptual coding tree was developed. Transcripts were coded inductively. Common codes were categorised into themes which were iteratively revised in response to additional information. Close attention was paid to whether themes emerged exclusively or commonly among different EM women. Representative examples of each theme were extracted relating back to the research question. Both investigators read the transcripts and extracted the data separately. Inconsistency and disagreement among researchers was resolved by repeated textual reference, comparison and discussion. The final themes were reviewed and defined with mutually agreed names. Demographic data were analysed by descriptive statistics. ResultsData saturation was reached after 30 interviews and all interviewees were included for analysis. Mean age of the participants was 38.8 years (range 27 to 58). Twelve women attained tertiary education, followed by secondary (N=11) and primary (N=7) education. More than half of the subjects were domestic helpers (DoH) (N=17) and housewives (N=8). They were mostly married (N=23). Eighteen interviews were conducted in English and 4 in Cantonese. English interpretation was needed in 4 Indonesian, 3 Urdu and 1 Hindi interviews. Summary of subject recruitment is shown in Table 1. Demographics of the participants are summarised in Table 2. Individual subject particulars are listed in Table 3. The knowledge score was the number of correct items scored in the quiz (full score 11). The range of score was 2 to 9 items. Three themes were identified from the analysis (Table 4):

1) motivators for CCS:

2) barriers to screening:

3) enhancement strategies

1) Motivators for CCSa. Internal motivatorsAll except two women expressed their intention to have PS. They felt reassured for good personal health reason and wished to have early diagnosis and treatment in case of any abnormality. Some of them reported they had personal history of cancers or other gynaecological diseases, making them more eager to perform PS. “I would rather find out or catch it early when it was pre-cancers or when it’s actually cancer… it is also a form of reassurance... I’ve had skin cancer and my birth mother has had breast cancer... It’s not with cervical cancer but I’m just careful about that” (E01, American, 55) “I think it is very important for every woman to have a pap smear, so we will know our body, if it’s still ok or something there.” (F05, Filipino, 48) b. External motivatorsHaving a family and medical professional recommendations further enhanced participants’ health awareness. Social and community support helped them take action to undergo PS. “I have children…you definitely want to catch things early…because now there’s more people than just me” (E04, British, 33) “doctor…told us also that it’s better we do the pap smear… my employer supports me… do the pap smear… even not Sunday, it’s on weekday, they just asked me to go, they pay with me” (F03, Filipino, 45) “one community center… invite Asian ladies to join and to get to know awareness about this test… healthcare doctor, and she suggest… you should go and do this test… she give me the address and she book… pap smear test for me” (P04, Pakistani, 36) 2) Barriers to screeninga. Health illiteracyLack of awareness of PS was a major reason for never screening among 15 subjects. Misconceptions about CC and the screening schedule contributed to discontinuation of screening. For example, a few subjects thought they did not need to have a PS if they were currently sexually inactive or asymptomatic. “because she doesn’t really have sexual activities… that’s why she wouldn’t go to have a pap smear… there’s no experience in doing it, so she has no idea what would happen” (I05, Indonesian, 40 (interpreter’s verbatim)) b. Restriction of public systemMost Filipino and Indonesian DoH are only free on Sundays and public holidays (PH), but most public PS providers are closed on those days. “we have lack of time… because we only have one day-off a week, and normally public hospital is closed” (F04, Filipino, 34) Some subjects also expressed difficulty in utilising the public services due to the inconvenient phone booking system, and unavailability of walk-in service “It is hard to book on phone, by computer, even not by anyone… in emergency department you just directly go any time, but in the clinic, the phone, that is the problem first of all” (P04, Pakistani, 36) Across different ethnic groups, not knowing where and how to receive PS service was commonly mentioned. “I found in Hong Kong, the private doctors are really expensive; I wasn’t aware there was anywhere…I should do the testing here in Hong Kong until this time” (E02, British, 50) “we don’t know where to go, and where to do the pap smear.” (F05, Filipino, 48) c. Language barrierFor South Asian ladies, especially Pakistanis, language barrier significantly deterred them from booking and attending the service. “our English is not too good, and that’s why she hesitate… to ask them in English, why we came here and what we want to do.” (P02, Pakistani, 31 (interpreter’s verbatim)) “She need interpretation… who will help me to get the appointment and I will go.” (P01, Pakistani, 27 (interpreter’s verbatim)) d. Practical barriersLack of time due to job and family duties was frequently mentioned, especially most of the subjects were DoH and housewives. Forgetfulness due to busy schedule also hindered them from adhering to the screening schedule. The legislation in HK requires DoH to live in their employers’ residence.27 It may not be easy for them to freely go out on weekdays. “Sundays that she can go out to get a pap smear… for weekdays…they might have pay cuts… it’s mostly just the job because she is taking care of a child, so she can’t really leave the place.” (I08, Indonesian, 47 (interpreter’s verbatim)) Cost was a concern for numerous subjects, particularly at private clinics. However after knowing that the prices for PS in the public and semi-government clinics were around $100- 300, then most of them felt it was affordable. “but here we need to pay a thousand dollars just for the pap smear or 800 dollars for the pap smear… So we cannot afford, especially if the employer would not like to… answer for that bill, so you need to do it yourself.” (F08, Filipino, 58) e. Emotional barriersFear of the unpleasant procedure was a common barrier. Fear of abnormal result also made some subjects avoid the test. Subjects across difference ethnicities voiced out the preference for a female practitioner to perform the PS to lessen the embarrassment of exposing their private parts. “I think it’s scared also. How they do this… I heard from some, they take some parts from inside” (N02, Nepalese, 30) “embarrassment… I don’t feel really discomfort or pain…just prefer a lady doctor for this type of investigation.” (E02, British, 50) 3) Enhancement strategiesNumerous ladies expressed that more publicity targeting foreigners is needed to introduce the CCS programme. One subject reflected that she only learned about the CCS service after delivery and received post-natal service in Maternal and Child Health Center (MCHC), otherwise she had no idea about CCS service in HK. “how I would have known… if it wasn’t because I gave birth. So, because I’m already in their clinic for… postnatal check-ups, then they tell me to come for the smears, so I don’t know how the system in Hong Kong works if you are just new into Hong Kong... they don’t get a reminder, they don’t get told”(E04, British, 33) One subject also preferred to have PS in MCHC in spite of the fact that she could afford private PS service. “I have the option I could have done it privately, but not everybody has an option…I think it’s easier to keep everything in the government clinic, because they have all my postnatal records and now they do my antenatal checks as well…it’s nice they have all my information.” (E04, British, 33) Some EM women expressed difficulty in booking or attending PS in public clinics, so they welcome PS in community centres or churches on Sundays. Numerous subjects also appreciated the current research to educate and advocate for EM women. “your study is very effective, it could help us… express what is in our heart…to tell the doctor… spare time for all of us …if there are churches that offer the room… will have people queuing for the pap smear” (F08, Filipino, 58) Some subjects preferred a reminder system so that they would remember it amidst their busy schedule. “I’m very busy at a certain time and then it tends to get put off… there’s reminder, I think that’s a really critical thing. Does the public hospital… send out little reminder cards?” (E01, American, 55) Some subjects felt shy to have PS alone, therefore a group of EM women attending PS together can reduce the shyness. “in our culture, this is a bit hesitate…if we go alone, we feel shyness… but if in group… if lady friends altogether… maybe the shyness will be less” (P02, Pakistani, 31 (interpreter’s verbatim)) Some highlighted the importance of health education to overcome the taboo and clarify misunderstanding. “coz I’m kind of brought up in Hong Kong, so quite modern, so not too shy about these things… it’s important to… take care of yourself and do proper health screening” (N05, Indian, 30)

Discussion

|

|