Barriers to exercise participation among

older Chinese adults attending a primary

care clinic in Hong Kong

Olivia B Y Choi 蔡寶瑜,David K K Wong 王家祺,Man-kuen Cheung 張文娟

HK Pract 2021;43:21-32

Summary

Objective:

To explore the level of physical activity (PA)

and the barriers to exercise participation among the

older adults attending a university primary care clinic in

Hong Kong.

Design:

Cross-sectional questionnaire survey

Subjects:

Patients aged 60 or above attending a

university primary care clinic in Hong Kong

Main outcome measures:

Level of PA as measured

by the validated short version of International Physical

Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), self-perceived internal

and external barriers to PA

Results:

Overall, 20% (47/235) of respondents had low

level of PA. The three most common internal barriers to

PA were found to be: “too tired” (59%, 139/235), “too

lazy” (52%, 122/235), and “medical problem” (47%,

111/235). The most common external barriers were:

“bad weather” (49%, 116/235), “lack of time” (37%,

87/235), and “no one to exercise with” (28%, 65/235)

Conclusions:

The study has identified the most

common barriers to exercise participation among the

older adults attending a university primary care clinic.

Healthcare providers can address these barriers and

develop strategies for the implementation of exercise

programmes in coming years.

Keywords:

exercise barriers, physical activity, older

adults, Hong Kong

摘要

目 標 :

探討在香港某所大學基層醫療診所就醫的老年患者

的身體活動(PA)情況和妨礙他們參加身體鍛煉的因素。

設計:橫斷面問卷調查

設計 :

橫斷面問卷調查

對象 :

在香港某所大學基層醫療診所就醫的60歲及以上

患者。

主要測量內容:

以經驗證的簡版《國際身體活動問卷》

(IPAQ)評估身體活動水準以及自我認為的妨礙鍛煉的

內、外部因素。

結果 :

總體而言,20%(47/235)的應答者身體活動

水準較低。妨礙鍛煉的三個最常見內部因素為“太

累”(59%,139/235)、“太懶”(52%,122/235)、“醫療

問題”(47%,111/235);三個最常見外部因素為“天氣不

好”(49%,116/235)、“沒時間”(37%,87/235)和“沒有

鍛煉夥伴”(28%,65/235)。

結論 :

本研究指出了某所大學基層醫療診所妨礙老年患

者鍛煉的最常見因素,醫護人員可藉此而制定未來開展

身體鍛煉的更佳策略。

關鍵字:

妨礙鍛煉的因素、身體活動、老年人、香港

Introduction

Background

Life expectancy of Hong Kong people rank

amongst the longest in the world. According to the

health facts released by Department of Health in 20191

,

the expectancy of life at birth for men and women in

Hong Kong was 82.2 years and 87.6 years respectively.

Because of the aging population, Hong Kong is facing

more non-communicable diseases (NCD) such as heart

disease, diabetes and cancer. This presents a serious

public health concern. In 2018, the Department of

Health and Food & the Hong Kong Health Bureau

developed a strategic health framework to prevent and

control NCD by 2025.2

One of the targets is to reduce

physical inactivity.

American College of Sports Medicine has launched

a global initiative called “Exercise is Medicine”. The

aim of this is to make both physical activity assessment

and exercise promotion the standard of clinical care.

Primary care physicians are encouraged to work with

their patients to incorporate exercise into their lifestyles.

In The University of Hong Kong (HKU), the University

Health Service (UHS) and the Centre of Sports (CSE)

have collaborated to support this initiative. In order to

have successful implementation of this initiative, full

understanding of the exercise barriers in our elderly

population is crucial in order to modify their exercise

behaviour. Although many studies have explored

the barriers to PA, there are limited local studies on

older adults in the Hong Kong primary care setting.

Therefore, more local research in this field is warranted.

Objecttive

Our study aims to (1) assess the amount and

intensity of physical activity of the older adults who

attend a certain university primary care clinic; (2)

identify the internal and external barriers that may

hinder their participation in exercise.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional, anonymous,

helper-assisted questionnaire survey. UHS attendees

who were Cantonese speaking and aged 60 or above

were invited to participate in this study during the data

collection period from November 2019 to January 2020.

The following groups of patients were excluded from

the study: (1) those who declined to take part or would

not give consent to the study; (2) those who could not

understand Cantonese; (3) those who were cognitively

impaired (as documented in their case notes); and (4)

those who had completed the questionnaires before.

The questionnaires would be distributed by healthcare assistants or registered nurses to suitable candidates

before their consultations. The patients would be asked

to complete the questionnaire with the assistance of a helper at the clinic. Two retired registered nurses were

recruited as voluntary helpers for this study. They were

required to attend a briefing session before the start

of the study in order to ensure that they had (1) clear

understanding of the definition of moderate and vigorous

activities; (2) full understanding of the questions; and (3)

complete understanding of the data collection procedure.

Close supervision and support were provided by

the principal investigator during the data collection

period. The completed questionnaires were collected by

the voluntary helpers and subsequently handed over to

the principal investigator for analysis. The completion

of the survey took approximately 10 minutes.

Study population and sampling

The participating clinic serves university students,

staff, dependants and retirees. The study population was

Cantonese-speaking clinic attendees aged 60 or above.

There is no general agreement on the definition of

“older adults” as aging is a dynamic process, and often

the definition is linked to the retirement age. The cutoff of age 60 was chosen as it is the normal retirement

age of university staff. The clinic population of those

aged 60 or above is approximately 4715. For sample

size estimation, the formula for cross-sectional studies

was used, where sample size (SS) = Np(1-p)]/ [(d2

/

Z2

1-α/2*(N-1)+p*(1-p)] [9]. Given a population size (N)

of 4715, a hypothesised proportion (p) of 0.2, and a

margin of error (d) of 0.05, the sample size required

was 234 with 95% confidence level.

Survey instrument

The short version of International Physical Activity

Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to assess the level of

PA in the last 7 days. The validity and reliability of the

IPAQ had been tested in 12 countries among adults aged

18 – 6510, as well as in Hong Kong.11 Further studies12-13

evaluated the validity and reliability of IPAQ used in

the elderly, and it was concluded that the short version

of IPAQ was a useful and valid tool for assessing PA

among elderly adults.

The IPAQ used in our study was the short Chinese

version (IPAQ-C) originally translated by Macfarlane

et al11 according to the procedures recommended by the

International Consensus Group for the Development of

the IPAQ and with cultural adaptations made. It involved

translation and back translation from the original English

version. The IPAQ-C was shown to be valid and reliable

for assessment in older Chinese adults.14

The barriers to exercise were assessed with a list of

items developed after review of previous studies, including

the focus group discussion by Larkin et al. in 200515, a

Hong Kong study by Chou et al in 200816 and a study by

Justine et al. in 2013.17 The final questionnaire consisted

of 18 questions that gave a comprehensive cover of the

perceived exercise barriers in older adults. The barriers

could be broadly divided into internal and external.

External barriers were those one might not be able to

control, and internal barriers were those which could be

determined by one’s own decisions.17-18 Participants were

asked to rate the barriers on a 4-point Likert scale (1 =

Not at all, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Occasionally, 4 = Always)

The content validity of each question was rated

on a 4-point Likert scale (not relevant, somewhat

relevant, quite relevant, and highly relevant). Based

on the proportion of experts who rated a question as

quite or highly relevant, the item-level content validity

index (CVI) was computed.19 The item-level CVIs of

all the questions were rated 1.00, thus the scale-level

CVI computed was also 1.00. Some wordings of the

questions were changed after review in order to make

it more reader-friendly. Pilot testing was performed

in 20 patients from different backgrounds before the

questionnaire was finalised.

Statistical analysis

Data was analysed using the open source software

“R” for statistical computing version 3.4.4 (2018-

03-15).20 Frequency tables were computed to check

for range and completeness. Descriptive statistics

were computed to summarise and express the data

in percentages, with calculated means and standard

deviations where applicable.

A multiple logistic regression analysis explored the

demographic predictors to low level of physical activity.

Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare the mean

Likert score on the barriers between those with low level

of PA and those with adequate level of PA. Mann-Whitney

U-test is preferred over t-test because the variables in

the two groups were not normally distributed. Statistical

significance was established at P < .05 for all tests.

Ethical consideration

This was an anonymous study. Participation was

voluntary and involved minimal risk. Those who agreed

to participate were deemed to have given consent for

their data to be used for research purposes. Refusal to

participate would not incur any negative consequences and

would have no impact on their medical care. Approval from

the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University

of Hong Kong was received before commencement of data

collection (Reference: EA 1910031).

Result

A total of 252 questionnaires were distributed and

240 were returned, which yielded a response rate of

95.2%. Among the returned questionnaires, five were

excluded from analysis due to grossly incomplete data (e.g.

missing most demographic data or a whole section of the

questionnaire). A total of 235 completed questionnaires

were used for final analysis. This represented about 5% of

the clinic population of those aged 60 and above (N=4715).

Socio-demographics

The characteristics of the respondents were shown

in Table 1. 53.2% (125/235) of the respondents were

female and 46.8% (110/235) were male. Approximately

half of the respondents were in the age group 60-64

(48.1%, 113/235). This survey was taken in a university

clinic setting. The respondents spanned all education

levels but about half of them completed tertiary or even

higher education (53.6%, 126/235). Majority of the

respondents were retirees (63.8%, 150/235). Although

77% (181/235) suffered from chronic medical conditions

requiring regular follow-up or treatment, more than half

of the respondents rated their own health as good, very

good or excellent (62.1%, 146/235), and only 3.4%

(8/235) rated their health as poor.

Level of physical activity

The respondents’ level of PA was assessed using

the short version of IPAQ. According to the IPAQ

scoring protocol 21, the total metabolic equivalent

(MET) score of each participant was calculated and the

participants were then categorised into three groups

according to their level of PA. The criteria of moderate

and high level of PA required total activity of at least

600 and 3000 MET-minutes/week respectively. Anyone

with a total activity below 600 MET-minutes/week was

categorised as low level.

Table 2shows the types and level of PA of our

study population. 20% (47/235) of the respondents had

low level of PA. 64.7% (152/235) had moderate level of

PA and 15.3% (36/235) had high level of PA. Walking

was the most common form of activity in all groups.

The percentage of contribution by walking in the low,

moderate and high-level activity groups were 81.3%,

65.2% and 57.6% respectively.

Demographic predictors of low level of physical activity

Multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 3) was

computed to explore the impact of various demographic

data on the respondents’ level of PA. PA level below

600 METS/min per week was used as the target

variable. After adjusting for other covariates, overall the

demographic variables were not very strong predictors

of low-level exercisers. They had minimal impact on the

level of PA except for age group 70-74 which showed a

significant P value of .034.

Barriers to exercise

Figure 1shows the ranking of the internal barriers

to exercise participation among the respondents. The

three most common internal barriers to exercise are “too

tired” (59%), “too lazy” (52%), and “health problem”

(47%). And the three most common external barriers are

shown inFigure 2. They are “bad weather” (49%), “lack

of time” (37%), and “no one to exercise with” (28%).

Among all the barriers, the least likely ones are “feeling

shy” (8%), “cost” (12%), “interfere with work” (13%),

and “lack of transportation” (19%).

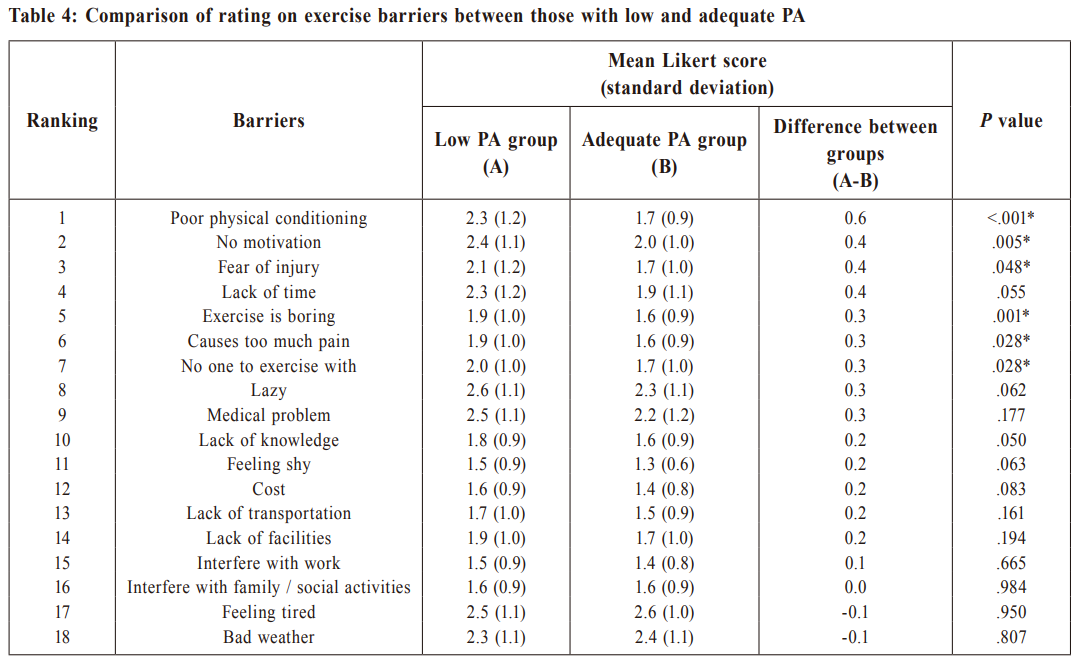

Comparison of impact of barriers between those with

low and adequate level of PA

According to the IPAQ scoring protocol21, anyone

with a total activity below 600 MET-minutes/week was

categorised as low level of PA. Table 4 shows the result

of the Mann-Whitney U-test comparing the mean Likert

score on the barriers between those with low level of

PA and those with adequate level of PA. Significant

differences were found for the following barriers with

P value < .05, which means that they are the important

barriers to the low-level exercisers: (1) poor physical

conditioning; (2) no motivation; (3) exercise is boring;

(4) fear of injury; (5) causes too much pain; and (6) no

one to exercise with.

Discussion

Principal findings

About 20% of the respondents were found to be

underactive, defined as less than 600 MET-min/ week.

This result is similar to the report published by the

Hong Kong Department of Health in 2015.8

Among

all the activities, it is worth noting that walking was

found to be the most common physical activity and

it contributed to about 63% of the total METS in our

study population. This was also observed in the Deng

et al.’s study14, in which the METS contributed by

walking was around 75%. Walking is a common form

of activity because it is simple and easily accessible.

A Japanese Study22 on elderly men without critical

illness found that walking for 2 or more hours per

day could lower the all-cause mortality. Thus, walking

should be promoted in the underactive elderly adults

because it can easily be fitted into their daily routine. In

addition, walking has a lower rate of injury.23 However,

multi-parameter exercise programme should also be

considered, including muscle strengthening and balance

exercise as advised by the World Health Organisation.24

studies showed that multi-component exercise

intervention could improve the balance and mobility25;

and help to prevent falls in older adults.26-27

Our study also illustrated the most common internal

and external exercise barriers.

The most common internal barriers were “too

tired”, “too lazy”, and “medical problem”. In Justine

et al’s study17, 51.7% respondents also considered

“too tired” as an important barrier to participation in

exercise among older adults. Therefore, the exercise

programme introduced to older adults should be

individualised. Introductory short sessions can be

considered to avoid exhaustion of the participants and

the intensity and duration of the exercise programme

can be adjusted accordingly.

Feeling too tired or being too lazy may also reflect

a lack of motivation, which is a significant determinant

of exercise participation28 and exercise adherence. 29

Lack of motivation was considered as a barrier in 37%

of our respondents. Motivation can certainly affect

behaviour. The question is how we can motivate people

to exercise. One study showed that participation in

sports during adolescent was associated with a higher

level of physical activity in later adulthood.30 Therefore,

exercise programme should be promoted early in life.

Larkin et al15 performed a qualitative study on 86

adults aged 65 or above using in-depth interview to

identify their perceived barriers to exercise. They found

that the most prevalent perceived barrier to exercise

among the respondents was "medical problem" (38%).

Our study had similar findings. As it is common for

those with chronic illness to believe that exercise may

do more harm than good, effective management of

their medical problems is essential. In addition to this,

primary care physicians should also give clear and

proper guidance on exercise programmes. The exercise

prescription should be tailor-made for the individual

and it should include the type, frequency, duration and

intensity.31 This is particularly important for low-level

exercisers. As shown in our study, these patients had

more fears of injury and more doubts in their ability to

undertake physical activity.

Among the external barriers, “bad weather”, “lack

of time”, “no one to exercise with” were found to be

significant barriers in our study. Studies other than ours

had shown that “lack of facilities” was a significant

external barrier16-17 but not in ours. This could be related

to the easy access to sports facilities at our University

for staff and retirees. The free access introduced in

2018 has further encouraged more staff and retirees to

participate in exercise and has made “cost” less of a

concern. In fact, cost was found to be one of the least

common barriers in our study.

In Chou et al’s study16, 38% of Chinese respondents

agreed or strongly agreed that “too hot” or “too cold”

was a barrier to do exercise. In our study, 49% of the

respondents believed that weather was a barrier to

exercise. Thus, indoor or home exercises programme

should be promoted among the older adults so that

their participation will be less likely to be affected by

adverse weather.

“Lack of time” was another major barrier found in

our study. This is consistent with previous research.16-17

Some studies found that small bouts of exercise can be

beneficial32 and improve adherence.33 This can be an

alternative for those who believe that they have little

time for exercise.

“Lack of transportation” was not found to be a

crucial barrier in our study. It makes sense as Hong Kong

has a highly sophisticated transport network, and this

makes most of the sporting facilities easily accessible.

In addition, our study showed that the most common

exercise was walking which can be performed anywhere.

By comparing between those with low level of

PA and those with adequate PA, we found that certain

exercise barriers had more significant impacts on the

low-level exercisers. In order to overcome the barrier

“no one to exercise with”, more group exercise classes

can be planned. Ideally, the class should be led by an

experienced fitness instructor, who can give proper

advice to the participants on how to improve their

fitness and how to prevent injury. That would help to

attenuate the concerns of “poor physical conditioning”

and “fear of injury”. Other benefits of group class

include making new friends among the participants and

making exercise less boring. Peer support may also

improve the motivation and adherence to the exercise

programme. In relation to the concern of “causing too

much pain”, apart from proper advice on warm up and

cool down, healthcare providers can explain to the

participants that the pain is only temporary and the

long-term benefits of exercise outweigh the pain.

Relevance to clinical setting

At HKU, the UHS has collaborated with the CSE

to support the initiative “Exercise is Medicine”. In order

for the implementation to be successful, our doctors

and our sport coaches should acknowledge the concerns

of the older adults and ensure that the prescriptions

are practical and achievable. There is no one-size-fitsall approach, especially in those with chronic medical

conditions. With the information obtained from this

study, we can develop better strategies in exercise

promotion among the older adults. The programmes

organised should be accessible, inexpensive and

enjoyable, e.g. easy trail walks. Proper guidance is

essential and small bouts of exercise can be considered.

If the above pilot programme is successful, it can then

be extended to the community

Strengths and limitations

Although many overseas studies were performed

to explore the barriers to PA or exercise, there are not

many local studies involving older Chinese adults in

Hong Kong, especially in the primary care setting. A

high response rate of 95% was achieved in our study.

Retired nurses were recruited to assist the completion

of the questionnaires and supervision was also given to

them in order to obtain high quality data.

As the study was taken in a university clinic,

the data is skewed towards more educated and

affluent patients, therefore the study’s external

validity is reduced. As the physical activity level

was self-reported, reporting bias was possible. More

accurate level of PA can be obtained if pedometer or

accelerometer are used for assessment of PA but it

would require more resources. Our study only explored

the exercise barriers, nevertheless it is also important

to explore the motivators as they can be inter-related.

Exercise behaviour can be affected by both. Therefore,

further study such as a focus group discussion can be

considered to explore the motivators of exercise.

Conclusion

Despite awareness of the various documented health

benefits, some older adults still do not have adequate

PA. This study highlighted the most common barriers

which may hinder their participation in exercise. In the

university setting, by acknowledging the above, the

UHS can work with the CSE to develop better exercise

programmes for their elderly staff and retirees. Physical

activity assessment and exercise promotion should be

part of the standard of primary care. In the community

setting, the same practice should be applied but that

will require collaboration between the government, nongovernment organisations, medical and non-medical

professionals. More resources should be allocated to

develop appropriate exercise programmes to promote

healthy aging. These will benefit the general population

in the long run and hence lessen the medical burden to

the society.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Mr. Tommy Lai for his

assistance in statistical analyses, and all the clinic staff

for their assistance during the research period.

Olivia B Y Choi, MBBS (New South Wales), FRACGP, MSpMed (New South Wales)

Physician

University Health Service, The University of Hong Kong

David K K Wong,MBChB (CUHK), FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Physician

University Health Service, The University of Hong Kong

Man-kuen Cheung,MBBS (HK), FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Director

University Health Service, The University of Hong Kong

Correspondence to: Dr Olivia B Y Choi, University Health Service, 2/F Meng Wah

Complex, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR

E-mail: ochoi14@hku.hk

References:

-

Department of Health facts of HK 2019. Available from: https://www.dh.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_hs/files/Health_Statistics_pamphlet_E.pdf

[accessed 2020 March 8]

-

Department of Health. Towards 2025 – Strategy and action plan to prevent

and control NCD in Hong Kong. 2018. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.

hk/files/pdf/saptowards2025_fullreport_en.pdf [accessed 2020 March 8]

-

Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health

in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports

Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

2007;39(8):1435-1445.

-

Hamer M, Lavoie KL, Bacon SL. Taking up physical activity in later life &

healthy. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:239-243.

-

Vagetti GC, Barbosa Filho VC, Moreira NB, et al. Association between

physical activity and quality of life in the elderly: a systematic review, 2000-

2012. Braz J Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):76-88.

-

McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, et al. Physical activity in older age:

perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology. 2016;17(3):567-580.

-

Alty J, Farrow M, Lawler K. Exercise and dementia prevention. Pract

Neurol. 2020;20(3):234-240.

-

Department of Health. Action plan to promote healthy diet & physical activity

participation in HK, 2015. Available from: https://www.change4health.gov.hk/

filemanager/common/image/strategic_framework/action_plan/action_plan_e.pdf

[accessed 2020 March 8]

-

Dean A, Sullivan K, Soe M. Open source epidemiologic statistics for public

health. OpenEpi. 2013. Available from: https://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_

Menu.htm [accessed 2020 March 1]

-

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity

questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

2003;35(8):1381-1395.

-

Macfarlane DJ, Lee CC, Ho EY, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese

version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(1):45-51.

-

. Tomioka K, Iwamoto J, Saeki K, et al. Reliability and validity of the

International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in elderly adults: The

Fujiwara-kyo Study. J Epidemiol. 2011;21(6): 459-465.

-

Chun MY. Validity and reliability of Korean version of International Physical

Activity Questionnaire short form in the elderly. Korean J Fam Med.

2012;33(3):144-151.

-

Deng HB, Macfarlane DJ, Thomas GN, et al. Reliability and validity of the

IPAQ-Chinese: the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort study. Med Sci Sports Exerc.

2008;40(2):303-307.

-

Larkin JM, Black DR, Blue C, et al. Perceived barriers to exercise in people

65 and older: recruitment and population campaign strategies. Medicine &

Science in Sports & Exercise. 2005;37(suppl 5):S12.

-

Chou KL, Marfaclane DJ, Chi I, et al. Barriers to exercise scale for chinese

older adults. Topics In Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2008;24(4):295-304.

-

Justine M, Azizan A, Hassan V, et al. Barriers to participation in physical

activity and exercise among middle-aged and elderly individuals. Singapore

Med J. 2013;54(10):581-586.

-

Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Laitinen JH. Barriers to regular exercise

among adults at high risk or diagnosed with type 2 diabetes: a systematic

review. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(4):416-427.

-

Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know

what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health.

2006;29(5):489-497.

-

R core team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

Vienna, Austria. R foundation for Statistical Computing. 2019. Available

from: https://www.R-project.org [accessed 2020 March 8]

-

. Patterson E. International physical activity questionnaire scoring protocol.

2010. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol

[accessed 2020 March 3]

-

Zhao W, Ukawa S, Kawamura T, et al. Health benefits of daily walking on

mortality among younger-elderly men with or without major critical diseases

in the new integrated suburban seniority investigation project: a prospective

cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;25(10):609-616.

-

Powell KE, Heath GW, Kresnow MJ, et al. Injury rates from walking,

gardening, weightlifting, outdoor bicycling, and aerobics. Med Sci Sports

Exerc. 1998;30(8):1246-1249.

-

World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health

65 years and above. 2011. Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/

publications/recommendations65yearsold/en/ [accessed 2020 March 8]

-

Bird M, Hill KD, Ball M, et al. The long-term benefits of a multi-component

exercise intervention to balance and mobility in healthy older adults. Arch

Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52(2):211-216.

-

. Ishigaki EY, Ramos LG, Carvalho ES, et al. Effectiveness of muscle

strengthening and description of protocols for preventing falls in the elderly:

a systematic review. Braz J Phys Ther. 2014;18(2):111-118.

-

Karlsson MK, Magnusson H, von Schewelov T, et al. Prevention of falls in

the elderly--a review. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(3):747-762.

-

Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW. The behavioral determinants of exercise: implications

for physical activity interventions. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2000;20(1):21-44.

-

Chao D, Foy CG, Farmer D. Exercise adherence among older adults:

challenges and strategies. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21(5 Suppl):212S-7S.

-

Tammelin T, Näyhä S, Hills AP, et al. Adolescent participation in sports and

adult physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(1):22-28.

-

Department of Health. Exercise prescription doctor’s handbook. 2012.

Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/archive/epp/files/DoctorsHanbook_

fullversion.pdf [accessed 2020 October 17]

-

Murphy MH, Hardman AE. Training effects of short and long bouts of brisk

walking in sedentary women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(1):152-157.

-

Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lang W, et al. Effects of intermittent exercise and

use of home exercise equipment on adherence, weight loss, and fitness in

overweight women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1554-1560.

|