Supporting dying in place in Hong Kong –

Retrospective analysis of a cohort of terminally

ill patients in public sector with a preference

for dying at home

Jeffrey SC Ng 吳常青, Pui-chi Chiu 趙佩芝, Po-tin Lam 林寶鈿, Ka-yee Lee 李家儀, Kai-ming Li 李啟明

HK Pract 2021;43:80-88

Summary

Introduction:

The prevalence of dying at home in Hong

Kong is extremely low. A cross-specialty multidisciplinary

program supporting dying at home was established

since 2011 in a cluster of regional public hospitals.

Objective:

This study aimed to review the profile of

patients in the program, to explore factors favouring

home death, interventions delivered at home, reasons for

admission for hospital death and events after home death.

Methods:

patients who joined the programme before

2019 were included. Information was searched through

the electronic medical records of Hospital Authority

Results:

53 patients were recruited, of median age 81

(range 29 - 102), 66% female and 50.7% with cancer

diagnoses. Most (96.2%) patients had family caregiver(s)

and 49.1% also had foreign domestic helper (FDH).

Thirty-two patients (60.4%) achieved home death.

Factors favouring home death included having FDH

(62.5% and 28.6%, p = 0.016), nursing visits ≥ 5 times

per week (71.9% and 42.9%, p = 0.035) and having less

emergency admission and admission to palliative care (PC)

wards in the programme (3.1% and 28.6%, p = 0.012;

3.1% and 23.8%, p = 0.031). Interventions at home

covered symptom control, psycho-spiritual support and

caregiver education. Having refractory symptoms was the

main reason (85.7%) for hospital death. For patients who

died at home, 87.5% (28/32) received cardio-pulmonary

resuscitation (CPR) by emergency rescue personnel (ERP)

upon transfer to hospital.

Conclusions:

Dying-at-home is achievable in Hong

Kong. Presence of professional support at home is an

important determinant. Legal barrier resulting in futile

CPR by ERP against patient’s wish is yet to overcome.

摘要

導言:

香港的居家離世率極低。從2011年起,一組地區公立醫院設立了一項支持居家離世的跨專業多學科專案。

目的:

本研究旨在對專案患者的基本情況進行梳理,探討居家離世的有利因素、可在家開展的介入措施、在醫院離世的原因以及居家離世後的事件。

方法:

納入了2019年之前加入本專案的患者。資訊通過檢索醫院管理局的電子病歷獲得。

結果:

共納入了53名患者,年齡中位數81歲(29歲–102歲),女性佔66%,癌症患者佔50.7%。大多數患者(96.2%)有家人照護,49.1%的患者還有外籍家庭傭工照護。三分之二的患者(60.4%)實現了居家離世。有利於居家離世的因素包括:聘用外籍家庭傭工(62.5%和28.6%,p = 0.016),護士家訪≥每週5次(71.9%和42.9%,p = 0.035),以及在專案中較少入住急症和紓緩治療病房(3.1%和28.6%,p = 0.012;3.1%和23.8%,p = 0.031)。在家中開展的介入措施包括症狀管理、心理精神支持以及照護者教育培訓。在醫院離世的主要原因為有難治性症狀(85.7%)。在居家離世的患者中,87.5% (28/32)在轉運至醫院的途中接受過緊急救援人員的心肺復甦術。

結論:

居家離世在香港是可以實現的。在家中提供專業支援是重要的決定因素之一。因法律障礙而導致緊急救援人員違背患者意願進行無效心肺復甦術的情況尚待克服。

Introduction

An important element of End-Of-Life Care (EOLC)

is to let people with terminal illness to receive care

and to die in their preferred place. The percentage of

people being able to die in place has been proposed to

be an element of good death1

and a quality indicator

in palliative care/ EOLC in some countries.2

Family

satisfaction with EOLC is also strongly associated

with their relatives dying in their preferred place.3

Among different locations of death, home is commonly

acknowledged as the preferred place.4

Dying peacefully

in one’s bed at home has also been recognised as a

blessing in traditional Chinese belief.5

About 90% of Hong Kong (HK) people died

in government hospitals6

, but a recent HK survey

suggested that 31.2% of general public chose home

to be the preferred place of death.7

The preference for

home death may decrease with progression of illness8

,

consistent with local findings that only 13-19% of

patients receiving palliative care preferred to die at

home.9,10 Nonetheless, an earlier study in HK reported

extremely low prevalence – only 6 in 1300 cancer

patients died at home as preferred.11 Barriers for dying

at home in HK are multifold, including the inadequate

care available at home, the lack of community

professional support as well as the legal and logistic

concern after home death.12

As an attempt to support care-in-place and

dying-in-place, a cross-specialty multidisciplinary

programme has been established in regional public

hospitals in Kowloon East Cluster (KEC) of Hospital

Authority (HA) since July 2011. This dying-at-home

programme consists two parts: 1. care-in-place until

death supported by a community professional team

with expertise in palliative care and 2. dying-in-place

facilitated by verification of death in the Accident and

Emergency Department (AED).

The professional support at home is provided by

the KEC Virtual Ward service, which aims to deliver

“hospital-at-home” to patients with high risk of hospital

admissions13 and was found to be effective in reducing

unplanned emergency medical readmissions and in

improving the quality of life in frail older patients

after discharge.14 Terminally ill patients are prone to

repeated hospital admissions and are one of the targeted

service recipients of this service. With collaboration

with community nursing service, community support

up to daily home visit can be arranged as needed. The

service provides on-site medical and nursing support at

home and enquiry hotline from 9am to 5pm on Monday

to Sunday. Clinical admission to PC ward could be

arranged so as to avoid AED attendance. Team members

consist of community nurses, a specialist palliative care

(PC) nurse, a PC physician and a geriatrician.

The verification of death after a patient passed

away at home was smoothed out by a workflow

established between AED and PC team. This workflow,

which is named “Palliative Care Last Journey”, ensures

that the Certificate of the Cause of Death (Form 18)

would be issued to the patient who died in AED, such

that the deceased body would not be sent to public

mortuary as a reportable death.15 The AED is informed

beforehand of the list of patients recruited in the dying-at-home program. Recruited

patients would be given a

letter with attention to AED stating patient’s terminal

illness and the preference for dying at home and

refusal of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The

standardised HA Advance Directives (AD) forms16 (if

the patient is mentally competent) and Do-Not-Attempt

Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) forms for

non-hospitalised patients (implemented since October

2014)17 would be signed in the programme. CPR would

be avoided in AED when patients were transferred

from home after death. The patient would be certified

dead by the AED doctors and the last office would be

performed by the AED nurses. The body is retained in

the hospital mortuary and the Certificate of the Cause

of Death (Form 18) would be completed by the PC

physicians.

People with advanced diseases receiving palliative

care service were referred for the dying-at-home

program. The criteria for enrolment are: (i) a clearly

stated preference for dying at home, (ii) such preference

accepted by the family and/or caregivers, (iii) having

at least one full-time caregiver and (iv) living in the

catchment area of United Christian Hospital (UCH) (later

extended to Tseung Kwan O Hospital in mid-2018).Patients with difficult symptom control

or inadequate

support from caregivers would be excluded upon initial

assessment. Since the establishment of this programme,

a significant portion of recruited patients have achieved

dying at home.

Objectives

This retrospective study would analyse the profiles

of the cohort of patients recruited into the dying-at-home programme. By comparing the

characteristics of

the subjects who died at home with those in hospital,

this study attempts to identify factors associated with

the place of death. This study will also explore the

interventions delivered during terminal care at home,

the reasons for final admissions in those who died in

hospital as well as the events after home death.

Methods

It is a retrospective cohort study. Patients who are

terminally ill and have been recruited in the above-mentioned dying-at-home programme

before 2019 and

living in UCH catchment area will be included in this

study. There is no exclusion criterion.

Information on patient’s place of death and data

on patient’s profile are extracted by review of the

electronic medical records of HA by the investigators.

Data collected are based on conceptual models

on determinants of place of death in systematic

reviews18,19, which include individual factors (including

demographics, patient’s preference), social factors

(including household members, characteristics of

caregiver, housing and social assistance), disease

factors (including diagnosis, functional status and

symptom profiles) and health care factors (including

care interventions at home and healthcare utilisation).

Functional status is assessed by using Palliative

Performance Scales (PPS) in this study. PPS uses five

observer-rated parameters (ambulation, activity and

evidence of disease, self-care, intake, and level of

consciousness). It is a reliable and valid tool and PPS

score has been found to be a strong predictor of survival

in patients receiving palliative care.20,21 Relatives' Stress

Scale (RSS) is used to measures caregiving stress of

family caregivers. It is a validated self-rated 15-item

scale with total score ranging 0 to 60 and score </= 23

suggesting low risk, > 30 suggesting high risk.22,23

Information on intervention in terminal care and

communication with patient and caregivers at home are

also based on documentation in the electronic medical

records. For the reasons of the last admissions in those

who died in hospital and the events after patients dying

at home, including any CPR by emergency rescue

personnel (ERP) or in AED, body being sent to public

mortuary and referral to coroner, they are retrieved

from AED records with supplemented information from

community nurses in dying-at-home programme.

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)

version 21 is used for statistical analysis. Descriptive

statistics will be used to summarise the patient's health

conditions, socio-demographic characteristics and

treatments/ interventions received after recruitment into

the dying-at-home programme until death. Normality in

continuous variables is assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov

Test. Comparison between the two cohorts (those dying at

home and those in wards) will be done by Pearson Chi-square (or Fisher’s exact test

(FET) if the sample value

is less than 5) and Mann–Whitney U test. A significance

level with a p value < 0.05 will be used for all analyses.

This study received the approval from Kowloon

East Cluster/ Kowloon Central Cluster Research Ethics

Committee, HA (Reference number: KC/KE-18-0180/

ER-1).

Result

Totally 53 patients were enrolled in the dying-at-home program in the period from Jul

2011 to Nov

2018 and were all included in this study. Table 1

summarises the information on patient demographics,

social background and disease characteristics. Most

patients (96.2%) had full-time family caregivers and

nearly half (49.1%) had foreign domestic helpers

(FDH) as caregivers living with patients. The overall

caregiver stress by RSS was low with median score

of 12 (Interquartile range (IQR) 6 – 23), as score ≤

23 suggesting low risk.22,23 Half of the patients had

cancer diagnosis, including colorectal 8 (29.6%), lung

6 (22.2%), liver 3 (11.1%), breast 3 (11.1%) and other

types 7 (25.9%) of malignancy. Functional state was

poor with PPS of median 40, i.e. mainly in bed, unable

to do most activities and mainly requiring assistance in

self-care. The median number of symptoms were 6 (IQR

5 – 7), with generalised weakness and poor oral intake

being the most prevalent (in >90% of patients).

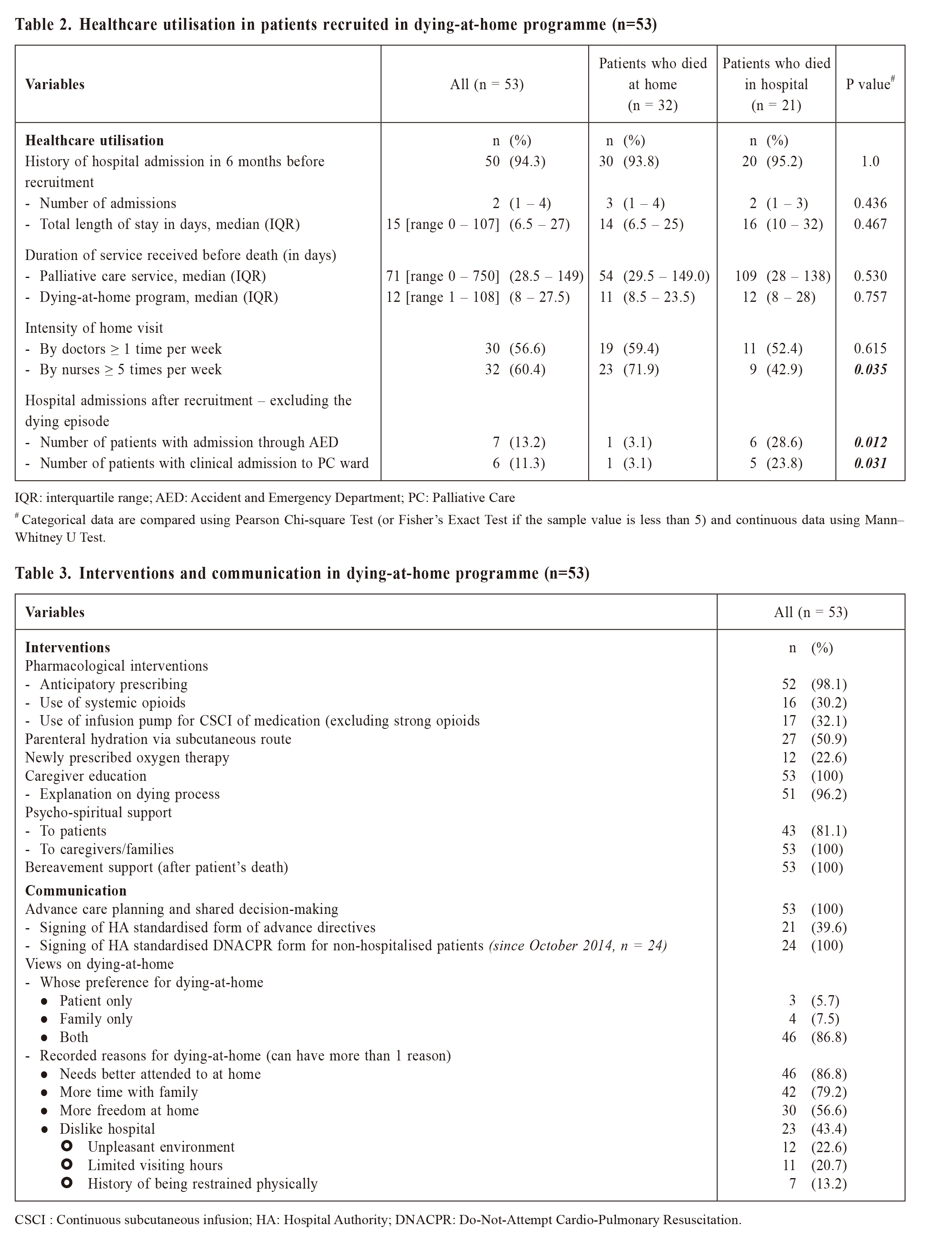

Table 2 shows the healthcare utilisation in patients

recruited in dying-at-home program. Most (94.3%)

patients had hospitalisation in the 6 months before

recruitment. Median duration of joining the dying-at-home program was 12 days (IQR 8 –

27.5 days). More

than half of the patients received doctor home visit

once or more per week and nursing home visit 5 times

or more per week within the programme. Around 10%

of patients still had hospitalisation despite intensive

support during the dying-at-home programme.

Thirty-two patients (60.4%) in the dying-at-home

programme achieved home death and the rest (39.6%)

died in hospital. Comparing those who died at home

with those in hospital, factors favouring home death

included having FDH as caregiver living with patient

(62.5% and 28.6% respectively, p = 0.016, FET),

received nursing visits ≥ 5 times per week (71.9% and

42.9%, X2

= 4.463, df = 1, p = 0.035) and having less

emergency admission and admission to PC wards during

the programme (3.1% vs. 28.6%, p = 0.012, FET,

and 3.1% and 23.8%, p = 0.031, FET, respectively).

Other demographic, social, disease and health care

variables are not found to have a statistically significant

association with the place of death.

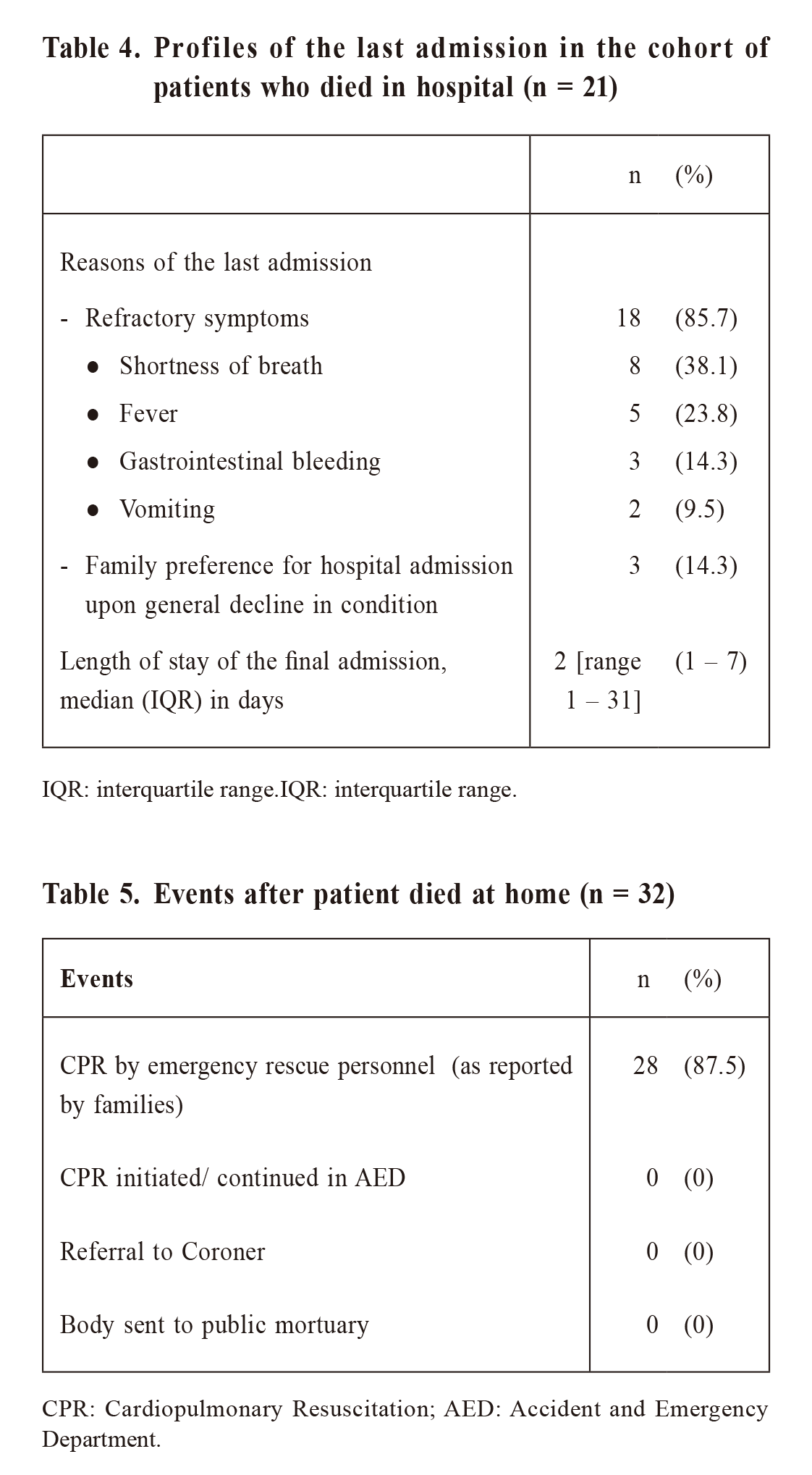

Table 3 shows the interventions and communication

in the dying-at-home programme. All except one patient

who died upon the first doctor visit had received

anticipatory prescription for symptom management.

Around 30% of patients used systemic opioids, including

tramadol (oral/ subcutaneous injection/infusion),

morphine (oral) and fentanyl (as transdermal patch).

One third of patients required continuous subcutaneous

infusion (CSCI) of medication, which included tramadol,

haloperidol, metoclopramide, hyoscine butylbromide

and furosemide. No strong opioids were administered

via CSCI route. Caregiver education was delivered

in all cases, which included symptom management,

use of medications, skills in bodily care as well as

explanation on signs of dying, potential catastrophic

events and practical procedures after home death. All

caregivers/ families received psycho-spiritual support

and bereavement care from community nurses in dying-at-home programme and from the

multidisciplinary

PC team. Advance care planning was reviewed in all

patients and HA standardised DNACPR forms for non-hospitalized patients were signed in

all after its rolling

out in October 2014. For the recorded reasons for

choosing home death, more than half mentioned that

their needs were better attended and there was more

time with family and more freedom at home. There is

no statistically significant difference identified in the

items listed in Table 3 between patients who died at

home and those in hospital.

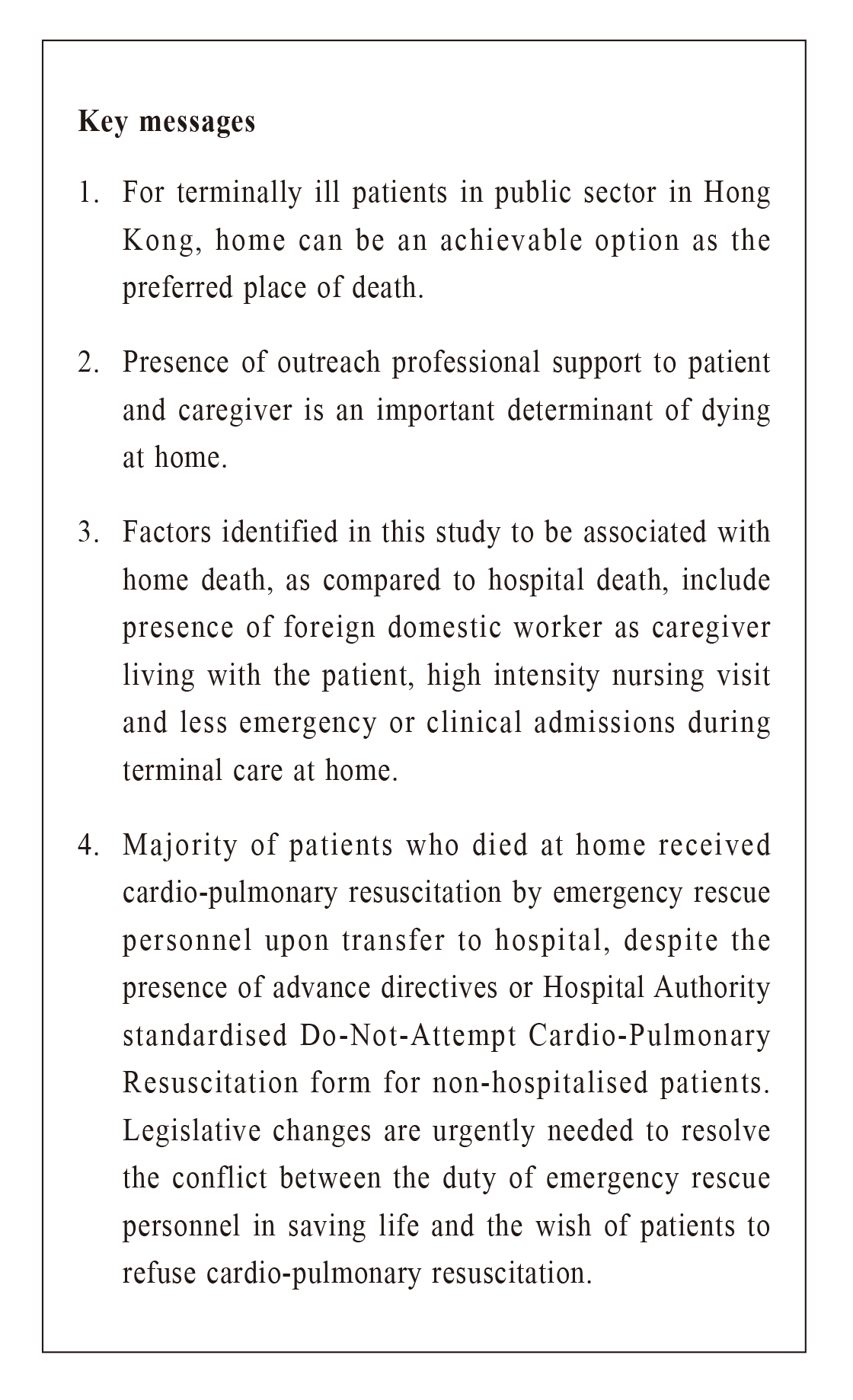

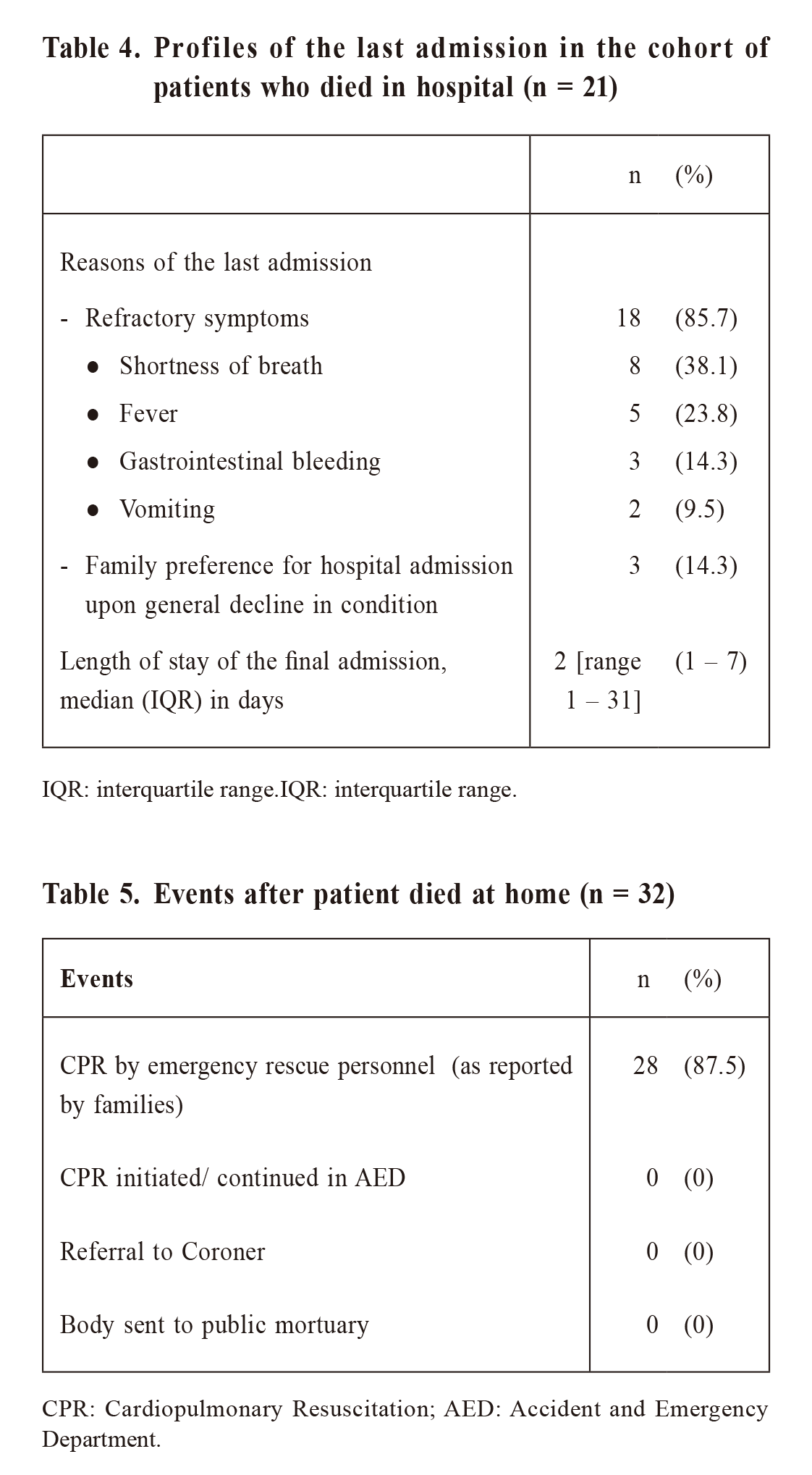

Among the patients who died in hospital, majority

(85.7%) was admitted for refractory physical symptoms

in which shortness of breath being the most common

(38.1%) (Table 4). In 3 (14.3%) patients, families

changed mind and preferred dying in hospital when

patients' condition further declined.

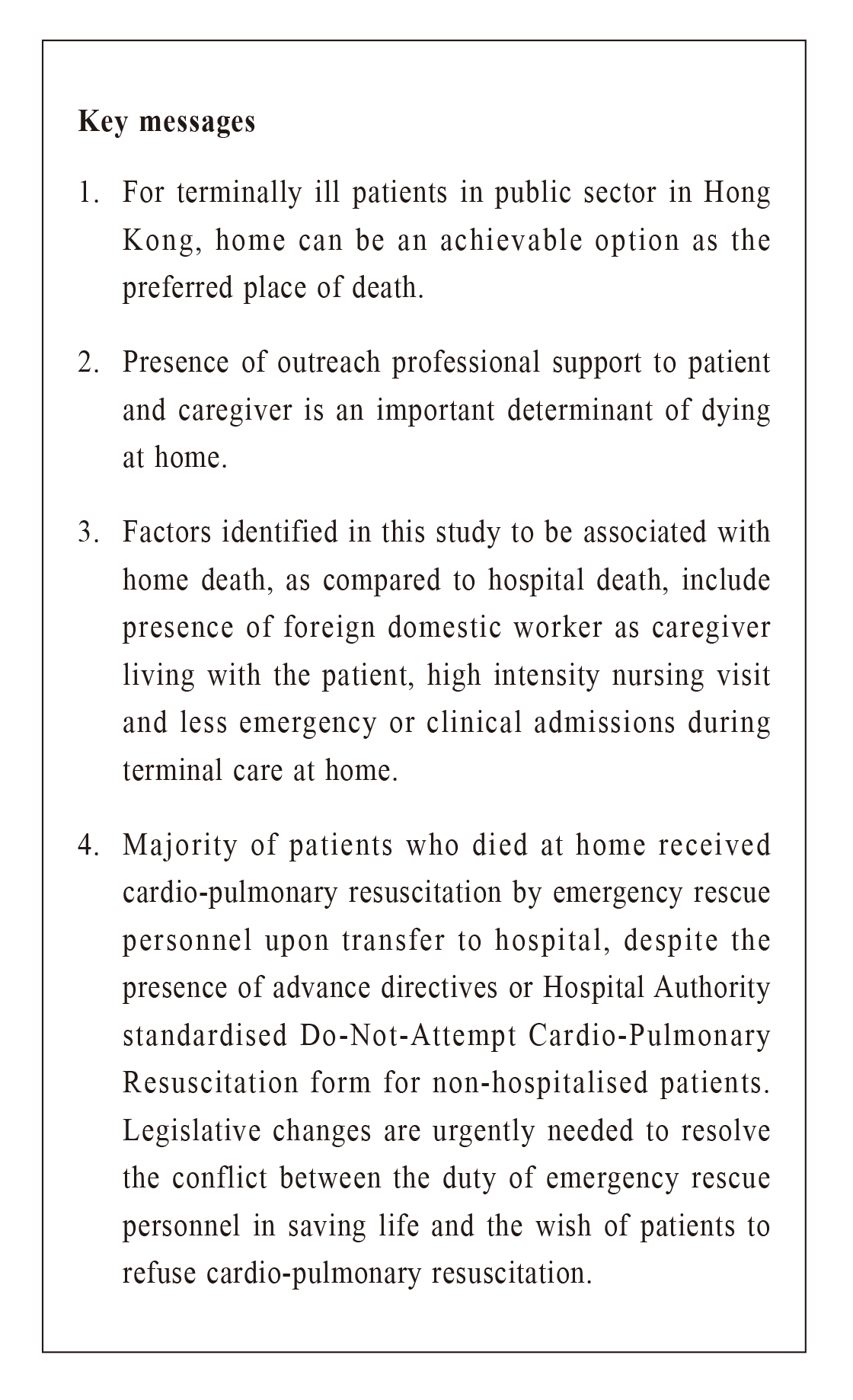

Table 5 shows the events in the cohort of patients

who died at home. Despite the presence of documents stating the preference against CPR,

families of 28

(87.5%) patients reported that CPR was performed by

ERP before arrival to AED. CPR was not initiated or

continued in AED. There was no referral to Coroner or

body being sent to public mortuary.

Discussion

Despite the extremely low prevalence of home death

in HK, more than half of patients in this study died at

home. This suggested that home can be an achievable

option in Hong Kong as the preferred place of death.

Factors associated with place of death

The criteria for recruitment in the program are

known to be factors associated with an increased

likelihood of home death, including the preference

of patient18,19, caregiver18,24 and family19 for dying

at

home, as well as the presence of relatives18 or informal

caregiver19 living with the patient. The presence of

home palliative care provided by doctors and nurses is

another important factor associated with an increased

likelihood of home death18,19,24,25

When comparing patients dying at home and those

in hospital in this study, having FDH as caregiver living

with patients is found to be associated with home death.

FDHs comprised 5% of HK population and covered

11% of local households.26,27 As most of the patients

who died at home (81.3%) and in hospital (95.2%)

already have full-time family caregivers living with

them, the specific caregiving role shared by FDH would

worth further exploration. The employment of FDH

may also indirectly reflect a better social condition and

higher economic status which favour home death.18,28,29

The current study does not find other sociodemographic

or illness factors associated with place of death. Lower

psychological stress in caregivers has been reported to

be associated with home death, but our study does not

find significant difference in the stress by RSS between

family caregivers of patients dying at home and in

hospital (10.5 and 13, Mann-Whitney U = 79.0, n1 =

22, n2 = 17, p = 0.624). A reason may be that families

under obvious high psychological stress could have

been excluded from the programme by the clinical team

upon recruitment assessment.

In this study, more patients who died at home than

those in hospital received high intensity of nursing home visit (5 times or more per

week). It is consistent

with previous review that intensity of home care

increased odds of home death18, reflecting the crucial

and heightened role of community nursing support in

the last days of life for patients dying at home. Patients

who died at home had fewer emergency admissions

through AED, consistent with previous report that prior

crisis related re-hospitalization would predict hospital

death.24 Patients who died in hospital had more clinical

admissions to PC ward and appeared to have received

longer duration (median 109 versus 54 days, not

statistically significant) of PC service. The experience

of support from in-hospital PC team or hospice unit

may increase the acceptance of admission for symptom

relief and has been identified as a determinant of

hospital death.19

Around 40% of patients admitted to hospital

when they were imminently dying, despite initial

preference on home death and presence of both lay

and professional support at home. Evolving physical

symptoms, which might not be well anticipated by

patients and caregivers, were the major reason of

admission. As an example, shortness of breath was

known to have its prevalence increased significantly

before death and was a common reason for PC patients

to visit AED.30 Taking care of a dying family member

at home could be physically and psychologically very

demanding. We found that some patients’ family might

finally choose hospital death, especially when the

imminently dying patient became mentally dull and was

apparently not aware of his/her location.

Professional support in community for patients

and families in the last days of life

Whether a patient with advanced illness can die

at home depends heavily on the healthcare services

available in the community. This study captured the

holistic approach in the dying-at-home programme

which includes symptom management to maintain

comfort and dignity as well as communication and

shared decision with the dying patient and people

important to them.31 For patients in community,

evidence suggested that palliative home care services

increased odds of dying at home and were effective

in reducing symptom burden.32 The importance of

caregiver education and empowerment could not be

overemphasised since the sustainability of keeping

terminally ill patients at home depends on how able they

are to care for their loved ones at home.18 The fact that

caregivers in this programme were trained to monitor

fluid and medication infusion and were informed of

the dying process may both have contributed to home

death.24

Use of strong opioids via CSCI is not feasible in

the dying-at-home programme. It is due to the present

lack of corporate guidance which could back up the

administration of dangerous drug (DD) via syringe

driver outside hospital setting. CSCI is a common

technique in contemporary palliative care and the use of

the compact syringe driver for CSCI allowed symptom

control at home for patients who no longer tolerate

oral medication.33 Use of strong opioids via CSCI is an

important intervention for patient dying at home with

pain and/ or dyspnoea. Guidelines on use of syringe

driver with DD in community should be established by

HA to overcome this barrier in the public sector.

Legal and logistic issues of home death in

Hong Kong

Without the availability of ad hoc doctor visit

for certification of death in the dying-at-home

programme, all patients would be sent to AED just

after death. Unfortunately, majority (87.5%) of these

patients had received CPR delivered by ERP, despite

the presentation of the valid and applicable advance

directives made by the patients or the DNACPR

forms written by the doctors. Currently in HK, ERP

of Fire Services Department (FSD) are bound by Fire

Services Ordinance (FSO) to perform CPR and other

related resuscitation to any person who appears to

need prompt or immediate medical attention.34 This

issue was addressed by Food and Health Bureau

in a public consultation in 2019.35 The recently

released Consultation Report have proposed measures

including the use of a statutory DNACPR form and the

corresponding amendment in FSO provisions to accept

this form.36 Such legislative changes are urgently

needed to resolve the conflict between the wish of the

patient and the obligation of ERP.

Before the legal resolution, an alternative way

might come from partnership with family physicians, in

which a registered doctor who has attended the patient

during his/her last illness can certify the death at home

and issue the Certificate of the Cause of Death (Form

18).37 With Form 18, the family can proceed to register

the death and thence legally move the body37 from

home through funeral service

Limitations

This study has a small sample size but provided

the very low preference of dying at home in Hong

Kong, this study offered initial findings in this area of

local research. Patients recruited in the dying-at-home

program were highly selected: clear preference for dying

at home, presence of full-time caregiver and receiving

a high-intensity professional support in community.

Therefore, the findings may not be generalisable to

other people with advanced life-limiting illness in

Hong Kong. However, the recruited patients still cover

a wide range of cancer and non-cancer diagnoses, age

groups and social background which may still provide

meaningful account of the profile of this specific group

of patients.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that home as a

preferred place of death is achievable in HK. Presence

of community palliative care service supporting patient

and caregiver is an important determinant. To avoid

unnecessary and futile CPR, there is a pressing need in

legislative changes to resolve the conflict between the

duty of ERP in saving life and the wish of patients to

refuse CPR.

Jeffrey SC Ng, MBBS, FHKAM (Medicine)

Associate consultant,

Department of Medicine, Haven of Hope Hospital, Hong Kong

Specialist in Family Medicine

Pui-chi Chiu, MSc, FHKAN (Palliative Care)

Advance Practice Nurse,

Department of Medicine, Haven of Hope Hospital, Hong Kong

Po-tin Lam, MBChB, FHKAM (Medicine)

Consultant,

Department of Medicine and Geriatrics, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

Ka-yee Lee, MNurs, FHKAN (Community and Public Health

Nursing)

Department Operations Manager,

Community Nursing Service, Kowloon East Cluster, Hong Kong

Kai-ming Li, MBBS, FHKAM (Emergency Medicine)

Consultant,

Accident and Emergency Department, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong

Correspondence to: Dr. Jeffrey SC Ng, Department of Medicine,

Haven of Hope

Hospital, 8 Haven of Hope Road, Tseung Kwan O, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: ngscj@ha.org.hk

References:

-

Smith R. A good death. An important aim for health services and for us all.

BMJ. 2000;320(7228):129-130

-

De Roo ML, Miccinesi G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Actual

and Preferred Place of Death of Home-Dwelling Patients in Four

European Countries: Making Sense of Quality Indicators. PLOS ONE.

2014;9(4):e93762.

-

Sadler E, Hales B, Henry B, et al. Factors Affecting Family Satisfaction with

Inpatient End-of-Life Care. PLOS One. 2014;9(11):e110860.

-

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, et al. Heterogeneity and changes in

preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care.

2013;12:17.

-

Tang ST. Meanings of dying at home for Chinese patients in Taiwan with

terminal cancer: a literature review. Cancer Nursing. 2000;23(5):367-370.

-

Hospital Authority. Strategic Service Framework for Palliative Care (issued

on 7 August 2017). Available at https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/ap/PCSSF_1.

pdf. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Chung RY, Wong EL, Kiang N, et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Preferences

of Advance Decisions, End-of-Life Care, and Place of Care and Death in

Hong Kong. A Population-Based Telephone Survey of 1067 Adults. J Am

Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(4):367.e19-367.e27.

-

Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative

systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med.

2000;3(3):287-300

-

Hong TC, Yau LM, Ng CC, et al. Attitudes and expectations of patients with

advanced cancer towards community palliative care service in Hong Kong.

Proceedings of the 2010 Hospital Authority Convention; 2010 May 10-11;

Hong Kong.

-

Woo KW, Kwok OL, Ng KH, et al. The preferred place of care and death in

advanced cancer patients under palliative care services. Paper presented at

the 10th Hong Kong Palliative Care Symposium; 2013 Aug 10

-

Liu FCF, Lam C. Preparing cancer patients to die at home. Hong Kong

Nursing Journal. 2005;4(1), 7–14.

-

Luk JKH, Liu A, Ng WC, et al. End-of-life care in Hong Kong. Asian J

Gerontol Geriatr 2011;6:103–106

-

Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Early discharge hospital at

home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD000356.

-

DLeung DY, Lee DT-F, Lee IF, et al. The effect of a virtual ward program

on emergency services utilization and quality of life in frail elderly patients

after discharge: a pilot study. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2015;10:413-

420.

-

Cap. 504 Coroners Ordinance. Schedule 1 [ss. 2, 4 & 55]. Part 1 Reportable

Deaths. Available at https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap504. Accessed on

7 Dec 2020.

-

Patient Safety & Risk Management Department / Quality & Safety Division,

Hospital Authority. Guidance for HA Clinicians on Advance Directives

in Adults (2020). Available at https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/psrm/

ADguidelineEng.pdf. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Patient Safety & Risk Management Department / Quality & Safety Division,

Hospital Authority. HA Guidelines on Do-Not-Attempt Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation (DNACPR) (2020). Available at

https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/psrm/DNACPRguidelineEng.pdf. Accessed on 7 Dec

2020.

-

Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally

ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):515-521.

Erratum in: BMJ. 2006;332(7548):1012.

-

Costa V, Earle CC, Esplen MJ, et al. The determinants of home and nursing

home death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Palliative Care.

2016;15:8.

-

Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, et al. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS):

A New Tool. J Palliat Care 1996; 12(1):5-11.

-

Francis Lau, G. Michael Downing, Mary Lesperance, et al. Use of Palliative

Performance Scale in End-of-Life Prognostication. J Palliat Med 2006;

9(5):1066-1075.

-

Ulstein I, Bruun Wyller T, Engedal K. The relative stress scale, a useful

instrument to identify various aspects of carer burden in dementia? Int J

Geriatr Psychiatry.2007;22(1):61–67.

-

Ulstein I, Wyller TB, Engedal K. High score on the Relative Stress Scale,

a marker of possible psychiatric disorder in family carers of patients with

dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):195-202.

-

Fukui S, Fukui N, Kawagoe H. Predictors of place of death for Japanese

patients with advanced-stage malignant disease in home care settings: a

nationwide survey. Cancer. 2004;101(2):421-429.

-

Lee YS, Akhileswaran R, Ong EHM, et al. Clinical and Socio-Demographic

Predictors of Home Hospice Patients Dying at Home: A Retrospective

Analysis of Hospice Care Association's Database in Singapore. J Pain

Symptom Manage. 2017;53(6):1035-1041.

-

Immigration Department, HKSAR. Statistics on the number of foreign

domestic helpers in Hong Kong provides figures concerning the number of

foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong https://data.gov.hk/en-data/dataset/

hk-immd-set4-statistics-fdh. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Research Office, Legislative Council Secretariat, HKSAR. https://www.legco.

gov.hk/research-publications/english/1617rb04-foreign-domestic-helpers-and-evolving-care-duties-in-hong-kong-20170720-e.pdf.

Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Gatrell AC, Harman JC, Francis BJ, et al. Place of death: analysis of cancer

deaths in part of North West England. J Public Health Med. 2003;25(1):53-8.

-

Barclay JS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA, et al. Association of hospice

patients' income and care level with place of death. JAMA Intern Med.

2013;173(6):450-6.

-

Kamal AH, Maguire JM, Wheeler JL, et al. Dyspnea review for the

palliative care professional: treatment goals and therapeutic options. J Palliat

Med. 2012 Jan;15(1):106-14.

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Care of dying adults in

the last days of life. Published 2 March 2017. Available at https://www.nice.

org.uk/guidance/qs144. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their

caregivers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. Art.

No.: CD007760.

-

Graham F, Clark D. The syringe driver and the subcutaneous route in

palliative care: the inventor, the history and the implications. J Pain

Symptom Manage. 2005;29(1):32-40.

-

Cap. 95 Fire Services Ordinance. Section 7 Duties of Fire Services

Department. Available at https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/

cap95!en?pmc=1&m=1&pm=0. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Food and Health Bureau. Public Consultation on End-of-life Care:

Legislative Proposals on Advance Directives and Dying in Place - Consultation

Document. Available at

https://www.fhb.gov.hk/download/press_and_publications/consultation/190900_eolcare/e_EOL_care_legisiative_proposals.pdf.

Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Food and Health Bureau. Legislative Proposals on Advance Directives and

Dying in Place – Consultation Report. Available at https://www.fhb.gov.

hk/download/press_and_publications/consultation/190900_eolcare/e_EOL_

consultation_report.pdf. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

-

Cap. 174 Births and Deaths Registration Ordinance. Part I Medical

Certificate of the Cause of Death. Available at https://www.elegislation.gov.

hk/hk/cap174?SEARCH_WITHIN_CAP_TXT=Certificate%20of%20the%20

Cause. Accessed on 7 Dec 2020.

|