A clinical audit on secondary preventive care

in patients with ischaemic heart disease in a

public primary care clinic in Hong Kong

Yin-mei Liu 廖燕媚, Chi-hang Lau 劉知行, Catherine XR Chen 陳曉瑞, Yim-chu Li 李艷珠

HK Pract 2022;44:106-115

Summary

Objective:

To audit the secondary preventive care in

patients with ischaemic heart disease (IHD) managed in

a public primary care clinic in Hong Kong.

Method: Study design:

Clinical audit with comparison

of two samples from a case series at different time

points.

Setting:

A public General Outpatient Clinic

(GOPC) in the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong.

Subject:

All stable IHD patients who had been regularly followed-up

at Robert Black GOPC during the audit cycle were

recruited. Evidence-based audit criteria and performance

standards were set after reviewing data from local and

overseas audit studies and latest international guidelines.

Phase 1 evaluation was performed from 1st June 2017

to 31st December 2017, and areas of deficiency were

identified. Active interventions were implemented for

12 months and Phase 2 evaluation was carried out

from 1st January 2019 to 31st July 2019. Chi-square test

and student’s t test were used to detect statistically

significant changes between Phase 1 and Phase 2.

Results:

Phase 1 data showed pronounced deficiencies

in the assessment and control of cardiovascular disease

(CVD) risk factors. For CVD risk factor control, only 34%

and 18.4% of patients can achieve the optimal blood

pressure (BP) control target and lipid control target

respectively. The glycaemic control rate was 49.3%

among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). Following

active intervention, marked improvements in outcomes

were observed. Phase 2 data showed that optimal

BP control rate and lipid control rate were achieved

in 58.5% and 58.4% of targeted patients respectively

(P<0.001), while the optimal glycaemic control rate was

improved to 70.5% (P=0.008).

Conclusions:

Through the process of identifying

deficiencies and implementing effective enhancement

strategies in managing IHD patients in public primary

care clinics, the control of CVD risk factors had been

significantly improved. It is postulated that the mortality

and morbidity of IHD patients would be reduced in the

long run.

摘要

目的 :

在香港醫院管理局轄下一所普通科診所對非急性缺

血性心臟病患者的二級預防進行循證審計。

方法 :

所有患有缺血性心臟病而病情穩定的病人,

如於審計週期內有於柏立基普通科門診定期覆診並

符合研究標準,將被納入本審計。本審計所取用的

準則與標準均於參照了本地及國際的審計與最新的

臨床指引之後釐定。透過於2017年6月1日到2017年

12月31日進行的第一週期評估,識別了處理不足之

處。再進行了12個月的積極改進,而第二期週期評

估於2019年1月1日至2019年7月31日進行。卡方檢驗

和學生檢驗被用於檢測第一期與第二期評估之間的

統計學顯著變化。

結果 :

第一期週期數據顯示了在心血管高危因素的評估和控制方面都存在明顯的不足。分別只有34%

及18.4%的病人能達到血壓及血脂的控制目標,而

49.3%的糖尿病患者能達致理想的血糖控制。經過

積極改進後,達到了明顯的改善。第二週期的數據

顯示分別有58.5%及58.4%的病人能達到血壓及血脂

的控制目標(p <0.001),而理想血糖控制率則上升至

70.5% (P=0.008)。

結論 :

通過於公營普通科門診識別對缺血性心臟病患

者二級預防的不足之處,再實施有效的管理策略,可

以顯著改善心血管高危因素的控制。據推測,此類心

臟病患者長遠之死亡率和發病率將降低。

Introduction

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) is an important

disease both in Hong Kong (HK) and worldwide.

Its incidence is increasing and it is associated with

significant morbidity and mortality. The World Health

Organization ranked IHD as the top cause of global

death in 2016.1 It caused more than 0.36 million deaths

in the United State in 20152 and contributed around 1.8

million deaths annually (20% of all death) in Europe.3

In Hong Kong, the number of in-patient discharges

and deaths due to IHD had risen by 45% in the past

decades.4 Local data in HK in 2017 showed there were

3,867 deaths (8.4% of all registered deaths) attributed

to IHD.5

There is strong evidence supporting comprehensive

risk factors modification via lifestyle changes and

medical treatment can help decrease mortality, reduce

risks of subsequent cardiac events, and improve quality

of life.6,7 However, quality of secondary preventive care

of IHD patients was far from optimal. A clinical audit

carried out in South Auckland in 2001 revealed that a

large proportion of post-IHD patients were not receiving

optimal care, with only 45% of dyslipidaemia, 39%

of diabetic and 59% of hypertensive patients having

achieved the desired treatment target. Only 34% of

patients were prescribed Angiotensin-converting Enzyme

Inhibitor (ACEI), and 29% patients were not prescribed

statins even when they were indicated.8 Another study

in the United State also revealed an underuse of statin

in post-IHD patients, with statin prescribed in 58.4% of

patients only.9

Previously, IHD management is mainly the

responsibility of cardiologists in the specialist setting.

With the increasing service demand in IHD care due

to an aging population and in view of the robust

development of family medicine in Hong Kong, more

IHD patients are advised to have continued care

by primary care doctors upon their discharge from

hospitals. For example, according to the preliminary

data from the Head Office of the Hospital Authority

(HAHO), over 50, 000 IHD cases are now being looked

after by family physicians in the General Outpatient

Clinics (GOPCs) of HA. In addition, over 50 percent

of attendances at the clinic where the author is working

are due to chronic disease management, with 6 percent

of chronic disease attendances being attributed to IHD.

Therefore, it is of paramount importance that IHD

care at the primary care clinics is regularly reviewed

to ensure that effective preventive measures are taken.

Having said so, local data on the performance of

secondary preventive care of IHD patients managed

in the public primary care settings is still lacking

until now. In view of this, this study aims to audit the

management of IHD cases from a primary care clinic of

HA and to work out improvement strategies. We believe

that by improving the standard of care of IHD patients

managed in the community via the audit approach, the

disease burden including the mortality and morbidities

of CVD could be greatly reduced in the long run.

Objective

Implications for clinical practice or policy

This clinical audit demonstrated common problems

encountered in secondary preventive care of patients

with non-acute ischaemic heart disease. Through the

process of clinical audit via a team approach targeting

at clinic, doctor, nurse and patient levels, noticeable

improvement in patient care was achieved.

Methods

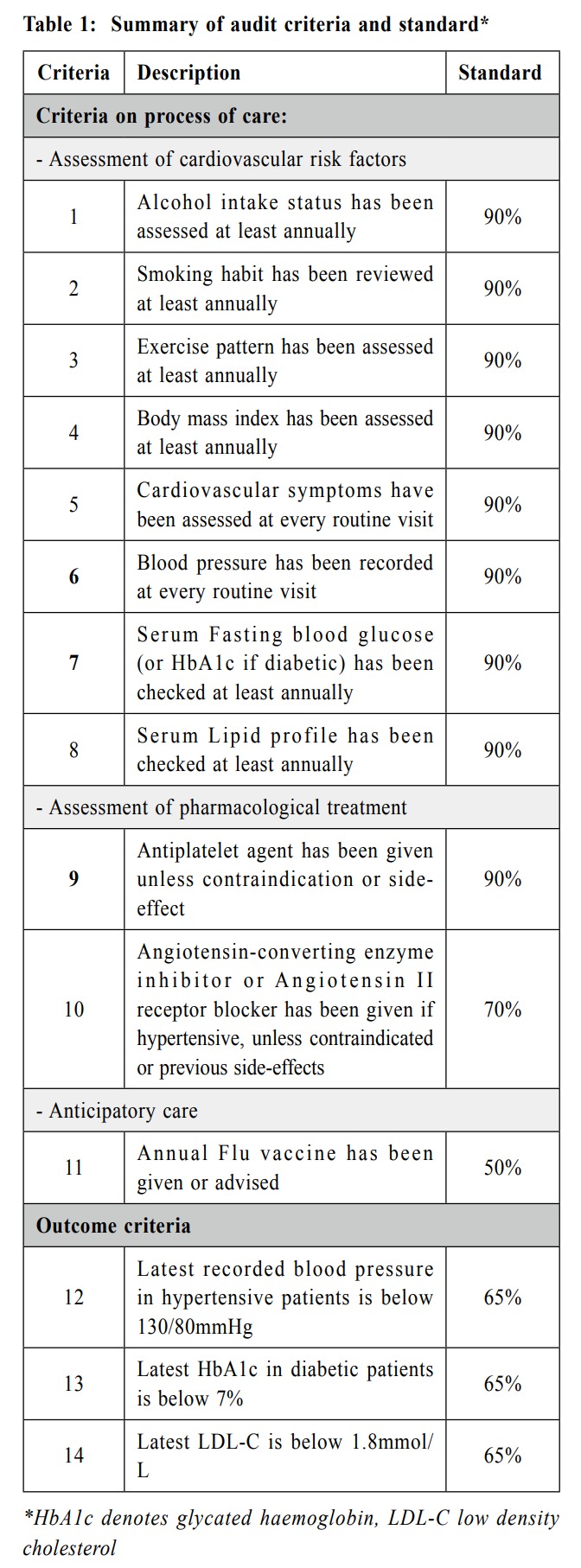

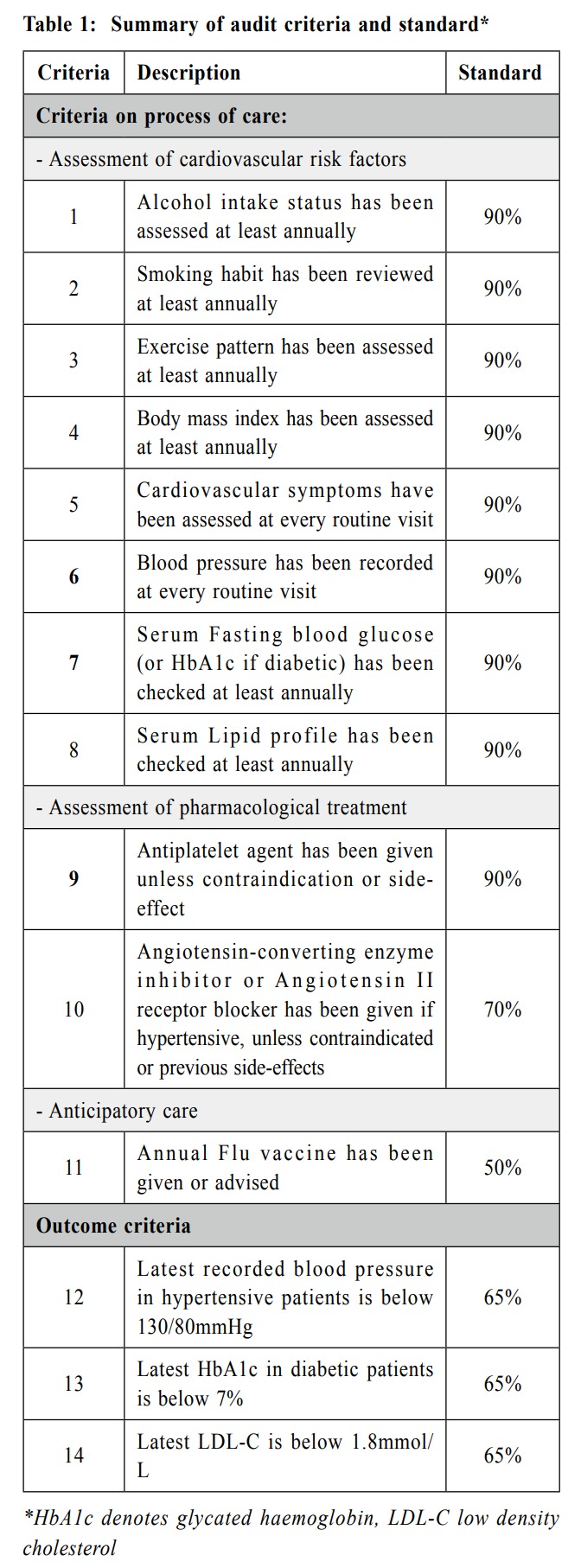

Setting audit criteria and justification of audit standards

Guidelines on IHD management published in

the recent 10 years were identified from the PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). After thorough

literature review, the following evidence-based audit

criteria and performance standards were adopted for this

IHD audit (Table 1).

The criteria were adopted from the following

evidence-based international guidelines:

-

Dyslipidaemias 2016 (Management of) ESC

Clinical Practice Guidelines” published by

European Society of Cardiology.10

-

AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk

reduction therapy for patients with coronary

and other atherosclerotic vascular disease:

2011 updated" by American College of

Cardiology Foundation and American Heart

Association.11

Criteria 1-8 were classified as ‘must do’ criteria

with the standard set at 90%, as these are important for

CVD risk factor or symptom identification for which

subsequent effective secondary prevention strategies

could be adopted. For criteria 12-14 (to assess outcome

performance on blood pressure, glucose, and lipid

control), the standard was set at 65% with reference to

local audit protocols on management of HT and DM12,13,

local audit and cohort study on secondary prevention

of stroke in primary care14,15, and regular reviews of

BP, lipid and glycaemic control in hypertensive and

diabetic patients in the primary care performed by the

HA. Table 1 summarised the criteria and standard of

this audit.

Audit subjects

All patients with stable non-acute IHD coded by

International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) K74

(IHD with angina) and K76 (IHD without angina) who

have been regularly followed-up at our Robert Black

GOPC during the audit cycle (phase 1 from 1 Jun 2017

to 31 Dec 2017 and phase 2 from 1 Jan 2019 to 31

July 2019) were included. Non-acute IHD refers to a

reversible supply/demand mismatch related to ischemia, a

history of myocardial infarction, or the presence of plaque

documented by catheterisation or computed tomography

angiography. Patients were considered stable if they

were asymptomatic or their symptoms were controlled

by medications or revascularisation.16 Exclusion criteria

were patients followed-up by Medical Outpatient Clinic

(MOPC), patients with sporadic consultation, wrongly

diagnosed patients, acute IHD, or those certified dead.

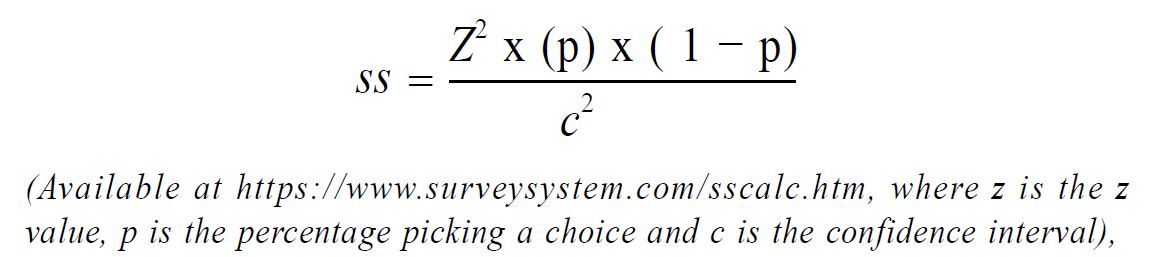

First-phase data collection

Totally 499 stable IHD patients were identified in

the first cycle. Assuming the confidence level being

95% and confidence interval being 5%, by using the

formula:

a sample size of 217 was needed. To allow room for

case exclusion, a total of 228 were selected. Therefore,

228 randomly chosen number from 1 to 499 were

generated using an online computer programme “Research

Randomizer” available at https://www.randomizer.

org/#randomize.17 Among the 228 patients included,

11 patients were excluded according to the exclusion

criteria, with 3 patients being followed-up in MOPC, 2

patients with wrong diagnosis, 2 patients with sporadic

consultation and 4 patients certified dead. The remaining

217 cases were included in the data analysis.

Implementing changes and intervention:

1st January 2018 to - 31st December 2018

After reviewing areas of deficiencies, a clinic team

approach with changes targeting at different levels were

adopted. Educational seminar was arranged for doctors,

with updated international guidelines and deficiencies in

disease management reviewed. Audit criteria summary

was affixed on the desk of all consultation rooms for

easy reference. Specific management plan was inputted

in the reminder in the CMS (Clinical Management

System) to facilitate communication with doctors.

Progress of intervention was reviewed via the monthly

clinic meetings.

At the nurse level, nurses were reminded to review

the patient’s lifestyle risk factors in particularly smoking

status, drinking habit and exercise pattern. Patient

counselling and education would be provided and were

based on updated guidelines. Possible deficiencies and

corresponding implementation strategies are summarised

in Table 2.

Second-phase data collection and analysis

504 IHD patients in total were found to have

regular follow-up in the clinic during the second cycle.

A sample size of 218 was needed to achieve the same

confidence level and interval as described in the first

cycle. To allow room for case exclusion, 233 cases

were randomly selected from the case cohort for review.

Among them, 15 patients were excluded (4 patients

followed-up in the MOPC, 3 patients with wrong

diagnosis, 3 patients with sporadic consultation and 5

patients certified dead) and the remaining 218 cases

were included in the data analysis.

Determination of variables

The patient’s age, gender, smoking and drinking

status, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP),

haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level if diabetic and lipid

profile were retrieved from the Clinical Management

System (CMS). The most recent clinic BP or blood test

were used for analysis if more than one reading or test

had been performed during the study period. The BMI

was calculated as body weight/body height2 (kg/m2).

Data analysis

SPSS software (version 25) was then used for data

analysis. The chi-square test was used to analyse the

categorical variables and paired student’s test was used

for continuous variables to identify the differences of

the measurements between the two phases. P value

<0.05 is considered as statistically significant.

Results

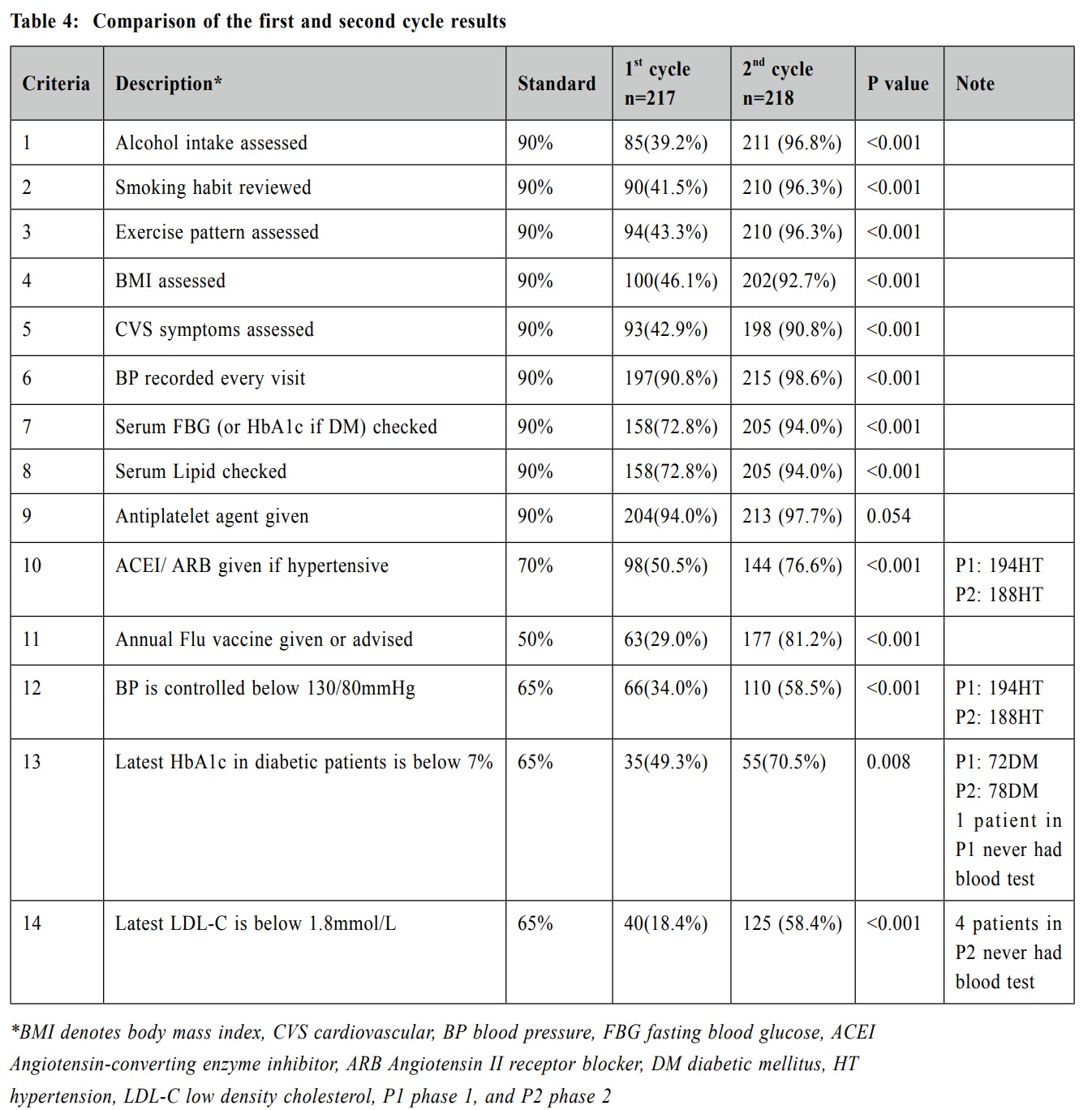

Table 3 summarises the demographic characteristics

of IHD patients recruited into the two phases. Their

background demographic parameters were comparable.

A comparison of the performance achieved in the two

phases is summarised in Table 4. Proper assessment of

CVD risk factor in phase 1 was far from satisfactory,

with inadequate documentation of alcohol use (39.2%),

smoking status (41.5%), exercise pattern (43.3%), BMI

(46.1%), cardiovascular symptoms (42.9%), blood sugar

(72.8%) and lipid profile (72.8%). Satisfactory BP,

glycaemic and lipid control were attained only in 34.0%

of the hypertensive, 49.3% of the diabetic and 18.4% of

dyslipidaemia patients respectively. Annual flu vaccine

was only given or advised in 29.0% of patients. Criteria

that met standard set included recording of BP (90.8%)

and anti-platelet given (94.0%).

After 12 months of active intervention and

implementation of changes, marked improvement in

most of these criteria was demonstrated in phase 2.

All of the 11 process criteria in the second cycle met

the desired standard. (criteria 1-11, all p value <0.001

except p value=0.054 concerning use of anti-platelet

agents). Optimal BP and lipid control were achieved in

58.5% and 58.4% of the targeted patients respectively

(P<0.001). 70.5% diabetic patients reached the set

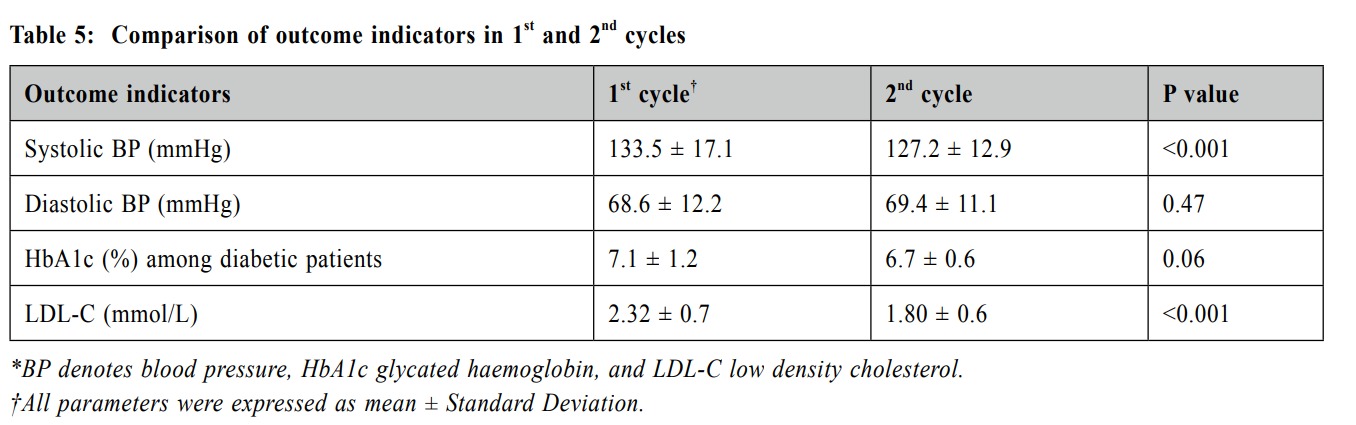

standard (P=0.008). Table 5 summaries the comparison

of outcome indicators in 1 st and 2 nd cycle.

Discussion

This study was the first local clinical audit on

secondary prevention of stable IHD in a public primary

care setting and has provided important background

information on IHD management in the community.

-

Criteria that did not meet standard in phase 1,

then met in phase 2:

Criteria 1-4

(assessment of drinking status, smoking

status, exercise pattern and BMI)

Assessment of these CVD risk factors was far

from optimal. Doctors’ lack of awareness on these

assessment and limited consultation time were

the main reasons. Following active intervention,

doctors’ awareness was enhanced and significant

changes were achieved. Similar standard was met

in other local studies. A local stroke audit achieved

a standard of >90% on evaluation of these risk

factors15. A local cohort study on stroke prevention

protocol also reached a standard of >90%, with the

exception of the assessment rate of BMI which was

79.3%14.

Criterion 5

(assessmenton cardivoascular symptoms)

Only 93 patients (42.9%) were properly

assessed about their CVS symptoms during the

first cycle. Most doctors expressed that they would

routinely discuss CVS symptoms with their patients

during their consultations. The low performance

index was likely due to poor documentation. Target

standard was reached in phase 2 (90.8%, P<0.001).

Criteria 7 & 8

(FBG/ HbA1c and fasting lipid checked)

Although not meeting the desired standard,

a relative good performance of 72.8% was found

in phase 1. Doctors were aware of the importance

of regular blood test but there was no consensus

on the regularity of blood test, with some doctors

checking it annually, some checking every two

years. Some doctors were less motivated to offer

blood test to the elderlies aged 90 or above, with

14.3% and 12.8% of IHD patients being 90 years

old or above in phase 1 and phase 2 respectively.

Some patients refused blood test due to busy

schedule or lack of awareness on the importance of

regular blood test.

After the concerted effect, the set standard was

met in phase 2. A local stroke audit also achieved

a standard of 91% in annual checking of glycaemic

and lipid control in the second phase15. Internal

data in HA showed 94.1% of diabetic patients had

HbA1c hecked within one year. Another local study

on the quality of diabetic care also showed it could

achieve >90% annual monitoring of lipid.18

Criterion 10

(use of ACEI/ ARB in hypertensive patients)

Only 50.5% of hypertensive patients fulfilled

this criterion in phase 1. This is consistent with

findings from the Hong Kong Cardiovascular

Task Force Risk Management Program showed

that 63.5% of hypertensive patients under medical

treatment were put on ARB.19 Some doctors were

not aware of recommendations on first line anti-hypertensive

agents indicated for IHD patients,

therefore knowledge gaps exist. Some doctors were

hesitant to switch current anti-hypertensive to ACEI/

ARB due to worrying about possible side-effects and

the inconvenience to monitor the renal function after

initiating ACEI or ARB. Furthermore, some patients

refused to change medications as they felt well with

their current regimen, or the BP control was already

optimal even without ACEI or ARB. Doctors were

more confident in initiating ACEI/ ARB following

active staff education and engagement. The set

standard was achieved in

phase 2.

Criterion 11

(seasonal influenza vaccine (SIV) was given or advised)

Only 63 (29.0%) IHD patients received SIV

in phase 1. This is partly explained by the fact that

many patients were still reluctant to receive the SIV

due to a fear of the side effects. In addition, patients

aged below 65 years without social benefit were

not eligible for the free SIV under the government

vaccination program (GVP) before 2018/2019, which

means that many indicated patients have to receive

the SIV out of their own pocket money. Fortunately,

GVP in 2018/19 extended its coverage to include

patients aged 50 or above, with subsidy for

injection in the private sector, and therefore much

more patients could benefit from this new scheme.

Doctors were also more aware of the importance

of flu vaccination and proactively promote it to

indicated patients. With all these facilitating factors,

the SIV coverage was much improved in phase 2

and the set standard was reached. This is consistent

with findings from an audit on secondary preventive

care of IHD in primary care performed in the United

Kingdom, where 67.0% of IHD patients got SIV

after the intervention.20

Criterion 13

(HbA1c <7% if diabetic)

49.3% of diabetic patients reached the

target HbA1c in phase 1. A large proportion of

patients were elderly with other co-morbidities

such as chronic kidney disease, stroke or vision

impairment, which might limit their choice of

oral hypoglycaemic agents and also their ability

to handle insulin injections. Doctors also tend to

accept looser glycaemic control in the elderly in

view of their higher risk of hypoglycaemia. After

educational activities, doctors were more familiar

with the recommended pharmacological agents,

and treatment targets for HbA1c. They were more

motivated to adjust medication to achieve better

cardiovascular risks factor control. 55 (70.5%)

patients achieved satisfactory glycaemic control in

phase 2 following these interventions, which was

slightly better than those achieved via other local

data noted. A local stroke audit reached a standard

of 62% in the second phase.15 The latest DM review

in the HA showed 58.8% and 62.9% of DM patients

in the HA overall and the author’s cluster achieved

HbA1c <7% respectively during the same period.

B.

Criteria that did not meet standard in both

phase 1 and phase 2:

Criteria 12 (BP < 130/80mmHg if hypertensive)

Only 66 (34.0%) hypertensive patients achieved

the target BP control in phase 1, which was

increased to 58.5% in phase 2 (P<0.001). Although

the improvement is prominent, there is still room

for further enhancement when compared with other

local data. For example, hypertensive review in

the HA has revealed a 79.5% achievement rate

of BP below 140/90mmHg among HT patients

during the same period. A local stroke audit aimed

BP <140/90mmHg for hypertensive cases and a

standard of 73% was achieved in the second phase.

Target BP < 130/80mmHg was set for diabetic

patients in the same audit and 61% of patients

had attained this target.15 A hypertension audit in

Malaysia reached 59% of standard in achieving BP

< 140/90 mmHg and < 130/80 mmHg in DM/ renal

impairment.21 Data in Canada showed BP control

rate at 60.1% in DM patients.22

The reasons accountable for this relative

suboptimal performance is multifactorial. On the

one hand, some doctors were not aware of the latest

guidelines on BP management for IHD patients

and therefore still took 140/90 mmHg as the target

BP. In addition, some doctors were concerned

about the risk of hypotension and fall in elderly

patients so they were less stringent on this target.

This is particularly a concern as a high proportion

of IHD patients were of an advanced age with

multiple comorbidities. Indeed, guideline from

American Heart Association suggests that patients

with frequent falls, advanced cognitive impairment

and multiple comorbidities may be at risk of

adverse outcomes with intensive BP lowering.23

An observational study showed an increased risk

of serious fall injury associated with the use of

antihypertensives in older adults, especially those

with a history of fall injury.24 Some patients and

their families also had similar concerns and they

refused to step up anti-hypertensives. HT with

whitecoat effect or whitecoat HT may also be one

of the reasons of not achieving the set standard,

however this was not assessed in this study.

Criterion 14 (LDL <1.8mmol/ L)

Only 40 (18.4%) IHD patients achieved target

LDL control in phase 1. Some doctors were not

aware of the treatment target of LDL level in

IHD patients. Some doctors were not initiating or

adjusting the dose of statin because of therapeutic

inertia, with only 72.4% of patients being put

on statin. Patients’ non-adherence to secondary

prevention treatment may also contribute to the

low LDL control rate. Indeed, several studies have

demonstrated that high levels of non-adherence

of cardiovascular medications exist among IHD

patients.25-27 For example, a meta-analysis revealed

low adherence rate of 54% for statins and 59% for

antihypertensives, in patients with CVD.26 Another

cross-sectional study in United Kingdom showed

rate of non-adherence to at least one secondary

prevention medicine in IHD patients was 43.5%.27

Though the standard was not reached in

phase 2, there was still significant improvement

in the lipid control rate from 18.4% to 58.4%.

Doctors were more knowledgeable on statin use

and they initiated the use of statin earlier apart

from offering advice on lifestyle modification. The

prescription rate of statin increased from 72.4%

in phase 1 to 83.5% in phase 2. However, doctors

expressed concern over the side-effects related to

high intensity statin use in older patients and they

tend to accept looser control with their LDL level.

What’s more, some doctors were less motivated to

intensify treatment when patients’ LDL level was

close to target. These doctors’ behavioural patterns

were well demonstrated in some local studies.

A local retrospective analysis in 2003 revealed

significantly lower prescription rate of lipid

lowering agents in patients aged 90 or above28,

while another study showed that therapeutic inertia

was common in the management of patients with

known CVD and a closer-to-normal LDL level.29

C.

Criteria that met the standard in both phase 1 and phase 2:

Criteria 6

(BP recorded) and Criterion 9 (antiplatelet agents given)

More than 90% of patients had BP recorded

in every routine visit. After review of consultation

notes and interview with doctors involved, we

found that some were missed due to patients’

refusal or busy consultation. These data

demonstrated that almost all primary care doctors

were well aware of the importance of regular BP

monitoring and the use of antiplatelet therapy in

the secondary prevention of patients with IHD.

Limitations of the audit

Firstly, as the study was conducted in public

primary care clinics of the HA, selection bias might

exist. The results from this study may not be applicable

to the secondary care setting or the private sector.

Nevertheless, these data should realistically represent

the IHD care in public primary care settings and provide

groundwork for future service enhancement. Secondly,

as the subject inclusion relied highly on the proper ICPC

coding and CMS documentation, patients not properly

coded or miscoded would be missed. The result may not

reveal the real clinical situation if the clinical assessment

were poorly documented in the CMS. Thirdly, some

factors that might affect patients’ cardiovascular

outcome were not assessed in this audit. For instance,

patients’ drug compliance, dietary habit and use of

allied health service etc. were not included in the data

analysis. Lastly, only short-term outcomes were assessed

in this audit and long-term outcome parameters like IHD

recurrence rate and mortality rate were not evaluated. In

addition, the relatively short implementation phase (12

months) might not be long enough for some criteria to

achieve the target standard.

Conclusion

Ischaemic heart disease is a common and important

disease worldwide and it causes significant morbidity

and mortality. Optimal control of CVD risk factors and

use of anti-platelet agents, statins and ACEIs or ARBs

are proven to be effective in reducing CVD related

morbidity and mortality. This clinical audit showed

significant improvement in both the process of care and

outcome of secondary preventive care among patients

with IHD managed in primary care. Future audit

focusing on the long-term outcomes such as recurrent

cardiac events and CVD related mortality should be

performed for better evaluation on the quality of care

provided to patients with IHD.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all medical and nursing

staff of the Department of Family Medicine & GOPCs,

Kowloon Central Cluster of the HA for their unfailing

effort and support to this clinical audit.

References

-

Top 10 causes of death [Internet]. [cited 2019Aug1]. Available from: https://

www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/

-

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke

statistics - 2018 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Vol.

137, Circulation. 2018. 67–492.

-

Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. Cardiovascular disease

in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. European heart journal.

2014;35(42):2950-2959.

-

Hospital Authority Strategic Service Framework for coronary heart disease

[Internet]. [cited 2019Aug2]. Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/ho/

corpcomm/Strategic%20Service%20Framework/Coronary%20Heart%20

Disease.pdf

-

Major Causes of Death [Internet]. [cited 2019Jul27]. Available from: https://

www.healthyhk.gov.hk/phisweb/en/healthy_facts/disease_burden/major_

causes_death/

-

A Matter of Your Heart: Coronary Heart Disease. [Internet]. [cited

2019Aug2]. Available from: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/ncd_watch_

jul2015.pdf

-

Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/

SCAI/STS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With

Stable Ischemic Heart Disease. Circulation. 2012;126(25).

-

El-Jack S, Kerr A. Secondary prevention in coronary artery disease patients

in South Auckland: moving targets and the current treatment gap [Internet].

The New Zealand medical journal. U.S. National Library of Medicine;

2003 [cited 2019Aug11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/14615806

-

Gamboa C, Safford M, Levitan E, et al. Statin Underuse and Low Prevalence

of LDL-C Control Among U.S. Adults at High Risk of Coronary Heart

Disease. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2014;348(2):108-114.

-

Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the

Management of Dyslipidaemias. European Heart Journal. 2016;37(39):2999-3058.

-

Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary

prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other

atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American

Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation

endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular

Nurses Association. Journal of the American college of cardiology.

2011;58(23):2432-2446.

-

Primary Care Office. Clinical Audit – Examples on Diabetes and

Hypertension Audit Making Use of the Reference Frameworks. [Internet]

Hong Kong; 2015. [cited 2019Jul29]. Available from: https://www.fhb.gov.

hk/pho/rfs/english/pdf_viewer.html?file=download67&title=string82&titletext

=string53&htmltext=string53&resources=12_en_Clinical_Audit

-

Primary Care Office. Hong Kong Reference Framework for Diabetes Care

for Adults in Primary Care Settings. [Internet]. Hong Kong; 2015. [cited

2019Aug4]. Available from: https://www.pco.gov.hk/english/resource/files/e_

diabetes_care_patient.pdf

-

Choi Y, Han J, Li R, et al. Implementation of secondary stroke prevention protocol

for ischaemic stroke patients in primary care. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 2015.

-

Chen CX, Chan SL, Law TC, et al. Secondary prevention of stroke: an

evidence-based clinical audit in the primary care. Hong Kong Medical

Journal. 2011 Dec;17(6): 469-477.

-

Braun MM, Stevens WA, Barstow CH. Stable coronary artery disease:

Treatment. American Family Physician. 2018;97(6):376–384.

-

Urbaniak, G. C., & Plous, S. (2013). Research Randomizer (Version 4.0)

[Computer software]. Retrieved on June 22, 2013, from http://www.randomizer.org/

-

Wong KW, Ho SY, Chao DV. Quality of diabetes care in public primary care

clinics in Hong Kong. Family Practice. 2012 Apr;29(2):196-202.

-

Cheung BMY, Cheng CH, Lau CP, et al. 2016 consensus statement on

prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the Hong Kong

Population. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 2017;:191–201.

-

Dunkley A, Stone M, Squire I, et al. An audit of secondary prevention of

coronary heart disease in post acute myocardial infarction patients in primary

care. Quality in Primary Care. 2006;14(1).

-

Chan SC, Chandramani T, Chen TY, et al. Audit of hypertension in general

practice. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 2005 Oct; 60(4):475-482.

-

Padwal RS, Bienek A, Mcalister FA, et al. Epidemiology of Hypertension in

Canada: AnUpdate. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2016;32(5):687–694.

-

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/

ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention,

Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults.

Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71(19):e127.

-

Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DSH, et al. Antihypertensive Medications and

Serious Fall Injuries in a Nationally Representative Sample of Older Adults.

JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014Jan;174(4):588.

-

Kolandaivelu K, Leiden BB, Ogara PT, et al. Non-adherence to cardiovascular

medications. European Heart Journal. 2014;35(46):3267–3276.

-

Chowdhury R, Khan H, Heydon E, et al. Adherence to cardiovascular

therapy: a metaanalysis of prevalence and clinical consequences. European

Heart Journal. 2013Jan;34(38):2940–2948.

-

Khatib R, Marshall K, Silcock J, et al. Adherence to coronary artery disease

secondary prevention medicines: exploring modifiable barriers. Open Heart.

2019;6(2).

-

Kung K, Lam A, Li KT. The use and efficacy of statins in Hong Kong

Chinese dyslipidaemic patients in a primary care setting. The Hong Kong

Practitioner. 2005;27:450-454.

-

Man FY, Chen CX, Lau YY, et al. Therapeutic inertia in the management

of hyperlipidaemia in type 2 diabetic patients: a cross-sectional study in the

primary care setting. Hong Kong Medical Journal. 2016 Aug;22(4):356-364.

Yin-mei Liu,

MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Resident Specialist,

Department of Family Medicine & General Outpatient Clinic, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority Hong Kong

Chi-hang Lau,

MBChB (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Private practitioner,

Catherine XR Chen,

MRCP (UK), PhD (Med, HKU), FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine & General Outpatient Clinic, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority Hong Kong

Yim-chu Li,

MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Chief of Service,

Department of Family Medicine & General Outpatient Clinic, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority, Hong Kong.

Correspondence to:

Dr. Liu Yin Mei, KCC FM & GOPC Department Office. Rm 622,

Nursing Quarter, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, 30 Gascoigne Road,

Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: lym873@ha.org.hk

|