Smoking cessation during the COVID-19

epidemic ‒ A new mode of intervention

Raymond KS Ho 何健生,Helen CH Chan 陳靜嫻,Grace NT Wong 黃雅婷,Patrick WY Fok 霍偉賢

HK Pract 2022;44:116-124

Summary

Objective:

The objectives of this study were: (1) to

study the feasibility of “mail to quit” smoking service

delivery and its efficacy; (2) to collect the views of

the participants; and (3) to evaluate the impact of the

service on the participants.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Subjects:

Eligible smokers recruited from 1st December

2020 to 31st January 2021 were recommended to use

the “mail to quit” service.

Main outcome measures:

The outcome measures were:

quit rate at 26th week, participants’ satisfaction score and

opinion score on the “mail to quit” service. A pre-test and

post-test questionnaire on project impact was adopted

from Donald Kirkpatrick’s four levels of evaluation.

Results:

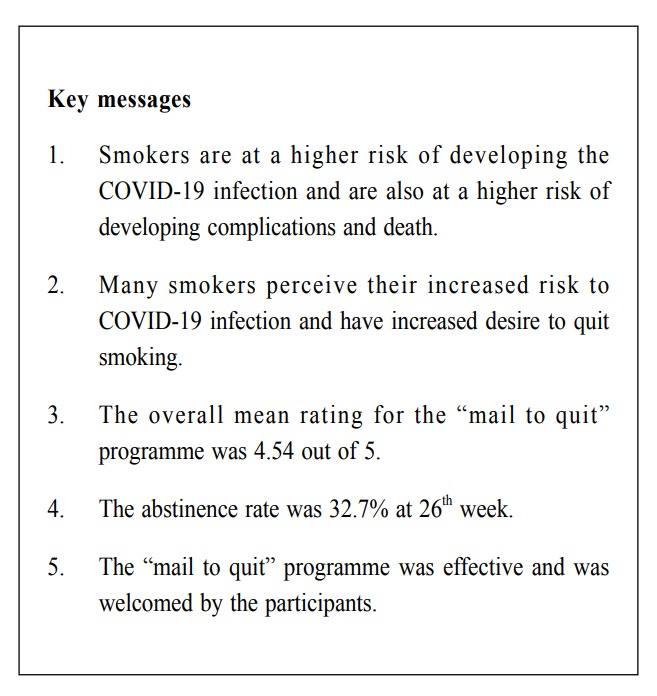

161 out of 215 smokers responded to our

survey, yielding a response rate of 74.88%. In the

area of impact assessment, self-perceived health, life

satisfaction score, knowledge gained, skill learned on

use of distraction method, buying cigarettes all showed

statistically significant improvement. The abstinence

rate was 32.7% at 26th week. The overall mean rating

for the “mail to quit” programme was 4.54 (SD 0.69).

Conclusions:

The “mail to quit” programme with

remote counselling during the COVID-19 pandemic was

a feasible and effective means to provide “smoking

cessation” intervention for smokers. It was well received

by smokers and had significant impact on their smoking

behaviour and knowledge gain.

摘要

目的 :

本研究的目標是:(1)研究“郵件戒煙”服務的可行性及有效性;(2)收集參與者的意見;以及(3)評估該服務。

設計 :

前瞻性群組研究

對象 :

招募從2020年12月1日至2021年1月31日符合條件的吸煙者使用“郵件戒煙”服務。

主要結果衡量標準 :

結果衡量標準是:第26周的戒煙率,參與者的滿意度得分和“郵件戒煙”服務的意見評分。關於專案測試前和測試後的影響,問卷採納了唐納德·柯克帕特里克的四個級別評估。

結果 :

215名吸煙者中有161人回覆了我們的調查,回覆率為74.88%。在影響評估、自我健康的認知、生活滿意度評分、獲得的知識、使用分心方法的技能、購買香煙都顯示出統計學上的顯著改善。第26周的戒煙率為32.7%。“郵件戒煙”計劃的總體平均評級為4.54(SD 0.69)。

結論 :

在新冠肺炎大流行期間,帶有遠端諮詢的“郵件戒煙”計劃為吸煙者提供了“戒煙”干預的可行性和有效性的手段。它深受吸煙者的歡迎,並對他們的吸煙行為和知識獲取產生了重大的影響。

Introduction

COVID-19 is a coronavirus outbreak that initially

appeared in December 2019 and it has then evolved

into a pandemic spreading rapidly worldwide.1 As of

17 April 2022, over 500 million confirmed cases and

over 6 million deaths have been reported globally as

reviewed by the WHO. This disease mainly affects

the lungs. Smokers are at a higher risk of developing

COVID-19 and are also at a higher risk of developing

severe COVID-19 complications and deaths.2 Smokers

may be at an increased risk of contracting the virus

due to reduced lung function, impaired immune

systems and cross-infection. Cigarette smoking also

increases the amount of forced vital capacity (FVC) and

stimulates hyperproliferation of the bronchial mucosal

glands, resulting in increased mucosal permeability,

excessive mucus production and inhibited clearance of

mucosal cilia, reducing the airway purification function

and harmful microorganism screening in the upper

respiratory system, leading to potential pulmonary

inflammation.3 A recent meta-analysis revealed that

current smoking increases the risk of severe COVID-19

infection by around twofold.4 Studies also suggested

that even 4 weeks of smoking cessation may decrease

the risk of adverse outcomes and respiratory failure

associated with COVID-19 infection.5

During this pandemic, the fear of contracting a

potentially fatal disease, confinement, the possibility of

being laid off and the stress from financial problems,

could increase the desire to smoke. However, smokers

may also perceive their increased risk to COVID-19

infection and its complications, hence may also increase

their desire to quit smoking.6

The need to remove the protective mask while

smoking can facilitate viral transmission. Some

governments have imposed a mandatory mask law, and

this can make smoking very inconvenient. In Hong

Kong, the SAR government had imposed a mandatory

mask law to curb the spread of COVID-19 infection.

In fact, some smokers had been fined because they

took off their masks to smoke in public. Hence the

COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity for

smoking cessation. In a survey by Elling et al, one-third

of the smokers were more motivated to quit smoking

due to the coronavirus.7

Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Integrated Centre on

Smoking Cessation (TWGHs ICSC) is a community-based

smoking cessation service funded by the Hong

Kong SAR Government. There are five centres in

our New Territories, and they provide free smoking

cessation services which include counselling and

pharmacotherapy to Hong Kong citizens. Counselling

is performed by experienced social workers who have

been trained in smoking cessation.

In view of the need for social distancing, staying at

home as much as possible and the potential increase in

smoking cessation demand, we initiated a “mail to quit”

programme offering the mailing of nicotine replacement

therapy (NRT) and phone or online counselling.

In the late 1990s, the International Society for

Mental Health Online (ISMHO) had already promoted

the use of online technologies amongst mental health

professionals. In 2001 comprehensive guidelines

were developed in the UK by the British Association

for Counselling and Psychotherapy (Goss et al.,

2001).8 Online counselling has numerous advantages.

It overcomes the need for travelling, enabling

psychological assistance and intervention without face-to-face contact. It is specifically beneficial for those

living in geographically remote areas. The visual

anonymity associated with telephone counselling can

decrease anxiety for the participants. They may be less

defensive and more willing to share their feelings and

difficulties.9,10 Reese et al. had studied the attractiveness

and client perception of telephone counselling in 2006

and gave a similar conclusion.11

Objective

The objectives of this study were:

-

to study the feasibility of this mode of service

delivery and its efficacy

-

to collect the views of the participants

-

to evaluate the impact of the service on the

participants

Methods

Study population

A prospective study was carried out to recruit

smokers to use the “mail to quit” services from 1st

December 2020 to 31st January 2021. The recruitment

part were smokers self-referred to smoking cessation

centres via telephone or QR code from advertisement

in Facebook, mini-buses, mobile truck in smoking hotspots

and smoking cessation hotlines operated by the

Department of Health. Participants could enrol in the

cessation services via telephone contact or QR code.

For those who used the QR code method, they would be

directed to a Google form so that they could fill in their

particulars, their smoking habits, and their preferred

time for future contacts by our counsellors. No personal

ID number was collected in the Google form and each

participant was assigned a clinic reference number

for identification. Participants should be able to read

and speak Chinese. Those who were aged less than 18

or above 60, allergic to nicotine replacement therapy

(NRT); had chronic medical or mental illness; recent

hospitalisation in the past six months, being pregnant or

practicing breast feeding and had contraindications for

the use of NRT were excluded. We limited participants

to these stringent criteria because it was a pilot study,

and we would like to play safe from the start. There

were multiple routes of recruitment because we would

like to recruit as many participants as far as possible.

Besides, we had to meet a performance pledge to

the Department of Health of HKSAR as there was a

significant drop in clinic visits due to the need for

social distancing.

Smoking cessation intervention

All eligible service users were invited to join the

study. A verbal consent for the study was explained

and obtained by counsellors over the phone at the first

intake. Information on the participants’ demographics,

smoking habits, past medical history were recorded.

Copies of consent forms were then mailed to the

participants, who were required to sign and return

the consent form to the investigators. After initial

assessment through the phone, two weeks supply of

the NRT were sent by mail to the eligible participants.

A phone call was made several days later to ascertain

the receipt of the NRT. Counselling, motivational

interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy

were then given by remote counselling via phone or

communication software (WhatsApp or WeChat) about

twice weekly until the end of treatment which lasted

from 8 to 12 weeks. The mailing package included:

-

instructions for the use of NRT,

-

a briefing on the principle and use of NRT for

smoking cessation; the preparation needed and

ways to deal with craving,

-

NRT patch, gum or lozenges, depending on the

clinical conditions.

A guideline on the use of remote consultation as

adapted from the UK National Health Service (NHS)

2020 National Centre for Smoking Cessation and

Training was issued to all counsellors to follow.12 All

interventions and counselling sessions were similar

to our conventional method of smoking cessation

programme.

All those reported to have adverse reactions were

assessed by counsellors and referrals to our clinic

doctor were arranged when necessary.

Outcome measures

A questionnaire on the impact of the current

programme, adopted from Donald Kirkpatrick’s

framework (knowledge, skill, attitude, behavioural change,

self-rated life satisfaction, self-rate health, self-rated job

satisfaction and self-rated family life satisfaction) was

carried out before and at the end of treatment, (Pre-test

and Post-test).12 The outcome measures were quit rate

at 26th week, participants’ satisfaction rating and their

opinion on the “mail to quit” service.

The quit rate was defined as 7-day point prevalence

abstinence and those who could not be contacted or

defaulted would be considered as not quit based on

the intention to treat principle. In view of the online

consultation, no biochemical validation of abstinence

was performed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for basic

demographics. Continuous variables were expressed as

mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables

were presented as numbers and percentages. McNemar’s

Chi square test, paired t-test and Fisher’s exact test were

used for pre- and post- intervention analysis of variables.

Results

Sample characteristics

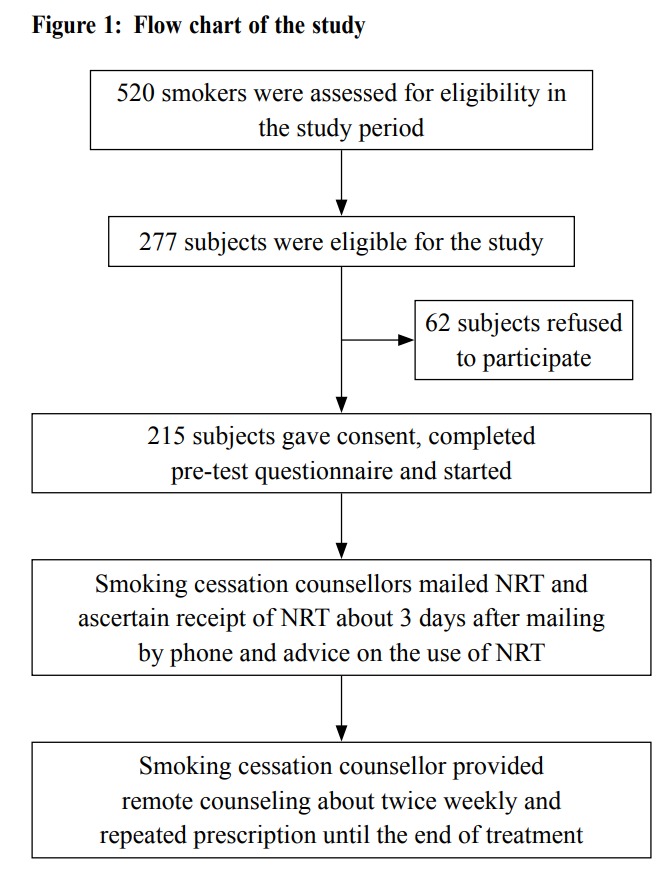

During the first intake, 215 subjects consented

to participate in the study (Figure 1). At the end

of treatment, 161 subjects responded to our survey,

yielding a response rate of 74.88%. The characteristics

of 215 and 161 participants were listed in Table 1.

More than 57% were in the age of 26 to 40 with a male

predominance. More than half of them were married

and more than 77% were employed. Most of them had

previous quit attempts, and about 56% lived in the

New Territories, a relatively remote area from the town

centre.

Impact assessment

Since only 161 subjects responded to our survey,

we limited this group to undergo pre- and post-treatment

analysis on the impact assessment and

their opinion on the “mail to quit” programme. In the

area of impact assessment, self-perceived health, life

satisfaction score, knowledge gained, skill learned on

the use of distraction method, buying cigarettes all

showed statistically significant improvement (Table 2).

There was no significant change in family relationship

and work efficiency.

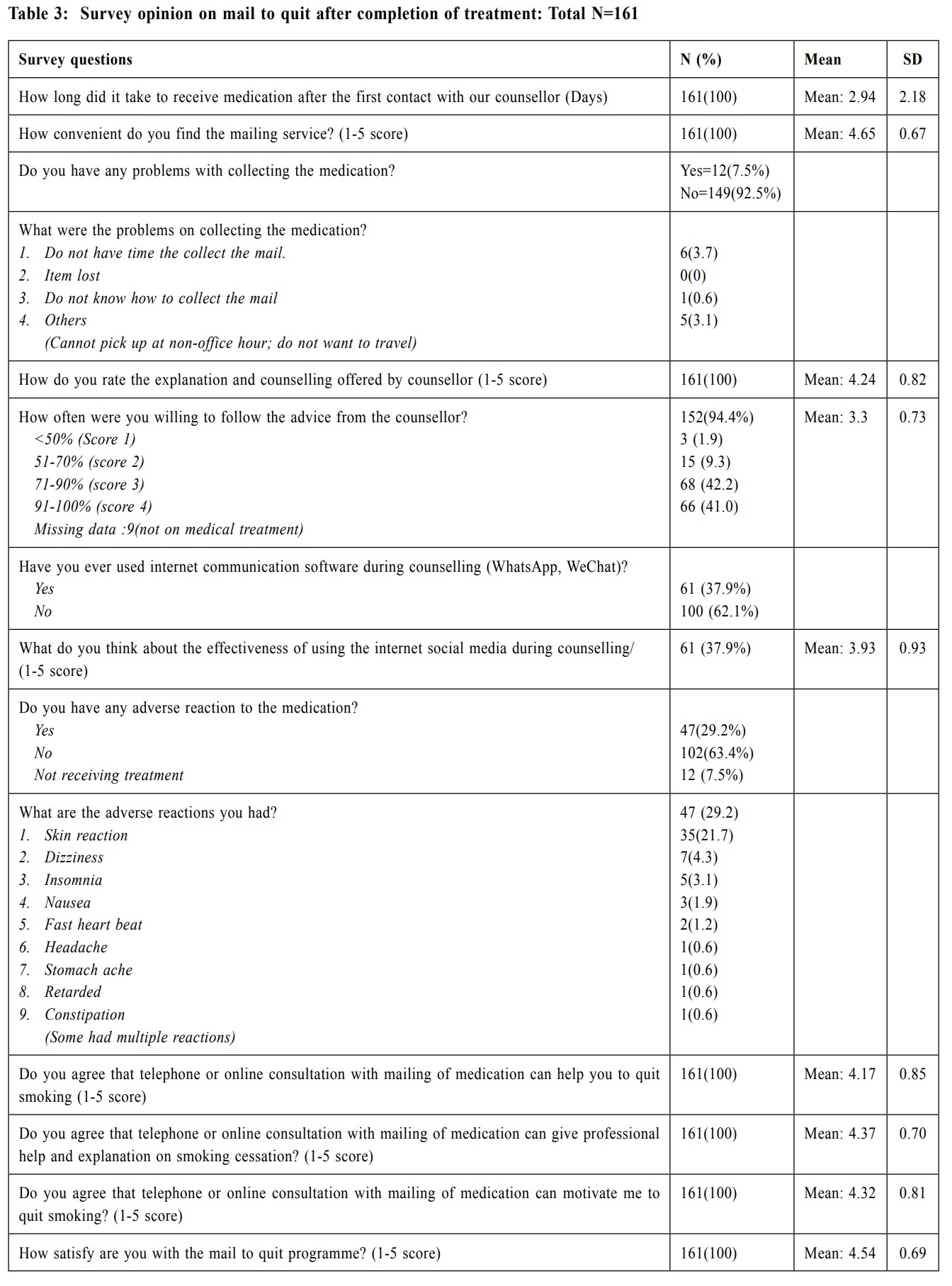

Opinion survey and abstinence rate

In the opinion survey, the mean score on the

convenience of “mail to quit” programme was 4.65 out

of 5 and this might be considered as remarkably high.

92.54% of participants did not have any problem in

collecting medication (Table 3). On average it took 2.94

days to secure the medication. 29.2% reported some

adverse reactions from NRT. This was similar to NRT

dispensed by conventional methods. All of the adverse

reactions were minor such as allergic dermatitis, and no

major adverse event was reported. The mean rating on

the explanation and counselling offered by counsellor

was 4.24 out of 5, and mean rating on the use of

social media for counselling service was 3.93 out of 5.

The mean rating on professional help and motivation

on smoking cessation were also high, 4.37 and 4.32

respectively. The overall mean rating for the “mail to

quit” programme was 4.54 out of 5 (SD 0.69).

There were 215 participants joining our treatment

programme initially and one withdrew later. due to

personal inconvenience. 70 participants reported total

abstinence (7-day point prevalence) at 26th week,

yielding a quit rate of 32.7%.

Discussion

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic

in February 2020 in Hong Kong, there was a dramatic

decrease number of smokers seeking smoking cessation

via our service in view of the need for social distancing

and fear of contracting the disease, despite a potential

increase in the need of smoking cessation from the

smokers. This pandemic provided us with an opportunity

to review our service and to modify our mode of service

delivery to meet the social distancing requirements. The

use of remote counselling together with mailing of NRT

was thought to be a useful alternative.

In our study, there was significant impact in terms

of self-rated health, life satisfaction score, knowledge

gain, skill and attitude change and behavioural

improvement. There were numerous studies on the

health impact and cost effectiveness of smoking

cessation programmes. However, we were not aware of

any study, either locally or overseas, on the impact of

a smoking cessation programme similar to our “mail to

quit” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the survey opinion with this programme, the

overall rating from the participants should be considered

as remarkably high. There was no excessive delay in

collecting the mail and more than 90% of participants

did not have any difficulty in getting the medication.

As to online counselling or telephone counselling, most

of them considered it to be effective, helpful, and able

to serve its purpose, and our counsellors were able to

motivate them to quit smoking. One point worth noting

is that the score on telephone counselling was higher

than counselling via communication software.

On the area of telephone counselling, a study

by An LC. et al. indicated that the telephone care

increased the use of behavioural and pharmacologic

assistance and led to higher smoking cessation rates,

compared to routine health care provider intervention.14

A meta-analysis review by Lichtenstein et al also

indicated that there was a significant increase in

cessation rates by proactive telephone calls compared

to control conditions.15 The abstinence rate at the 26th

week of the current study was 32.7% and this was

comparable to a study by Macleod et al16 who used

telephone counselling as an adjunct to nicotine patches

in smoking cessation and reported a quit rate of 30.7%

at 6 months. However, the methodology of this study

was totally different from ours. According to overseas

experience, the average abstinence rate at 26th week was

20-25%. On the other hand, our abstinence rate at 26th

week with conventional method over the past five years

was around 43%. This implied that the ‘’mail to quit’’

programme should be considered satisfactory, although

it was lower than our conventional method. This could

possibly be due to the fact that face-to-face counselling

was used in conventional method.

In our study, the ‘’mail to quit’’ service was carried

out via one-to-one communication rather than ‘’open’’

messaging, public sharing of information or group

counselling. We mailed NRT to the participants without

urging them to come to our clinics. This could save

their opportunity cost on travelling and time spent. This

was much welcomed by the participants as seen from

the result of this study. As to the efficacy of mailing of

NRT, a study by Cunningham et al has provided evidence

of the effectiveness of mailed nicotine patches without

behavioural support to promote tobacco cessation.17

Self-reported abstinence rates were significantly higher

among participants who were sent nicotine patches

compared with the control group (odds ratio, 2.65; 95%

CI, 1.44-4.89). In our study, we have not isolated the

effect of mailing NRT alone, although the combined

effect of remote counselling and mailing of NRT was

remarkable. Based on overseas and the present study,

the future of remote counselling on smoking cessation

appears favourable and effective.18,19

The users of remote counselling sampled in this

study found it appealing and attractive. It is particularly

convenient to those who have to work shift duties or

unconventional office hours, or those who cannot afford

to come to the clinics. The enrolment by QR code and

Google form can be conducted 24 hours a day, hence

making enrolment much easier. However, counselling

via telephone or communication software may not be

best for clients who prefer to see their therapist and for

clients who were experiencing severe problems such

as unstable mental condition. Another downside of

telephone consultation is that we could not detect any

non-verbal cues from the participants, their attention

span or their understanding during the consultation. In

real practice, some participants may be distracted by

something else during the consultation process. In the

present study, we have also excluded old- age clients,

clients with chronic medical illness and mental disease

to avoid risk and complications.

Limitations

There were a few limitations in this study. This is

an observational study on smokers who were relatively

healthy. They did not have any chronic medical

conditions or mental illness. They were adult smokers

who were aged 60 or below. Therefore, the result cannot

be extended to the whole smoking population. There

was no control group to compare with the effectiveness

of this mode of intervention and there were no

benchmarks for the scores. There are many facets of

impact assessment and we only limited it to the Donald

Kirkpatrick’s four levels of evaluation.20,21,22 Our survey

questionnaire was self-devised with reference from

Donald Kirkpatrick’s method, hence there was no gold

standard. The quit rate is self-reported abstinence and

there is no biochemical validation, although consensus

statements indicate that biochemical validation of tobacco

cessation may not be required in the present study.23

Conclusion

In conclusion, the “mail to quit” programme with

remote counselling during the COVID-19 pandemic

is a feasible and effective means to provide smoking

cessation intervention for smokers without chronic

medical illness with a satisfactory abstinence rate. It is

feasible in terms of administrative procedure, solving

technical issues and setting up guideline for remote

consultation and smoker’s acceptance. It reduces the

risk of social contacts and social exposure during

travelling, hence reducing the risk of contracting the

virus. There is significant impact on the participants,

both in terms of quitting, behavioural change, and

knowledge gain. The programme is perceived to be

very convenient, helpful and useful and is well received

by the smokers. A further large scale control study is

worthwhile to validate our findings.

Ethical approval and consent from participants

This study was approved by the Research Ethics

Committee of the Tung Wah Groups of Hospitals (No.

R2021007). Written informed consent was obtained from

all participants prior to their enrolment in the study.

Funding

There is no special funding source for this study.

The smoking cessation service was funded by the

Department of Health HKSAR Government.

Potential competing interest

Nil declared.

Acknowledgement

We thank all staff involved in this project.

References

-

Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential

domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating

in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225): 689-697.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9.

-

Vardavas CI, Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of

the evidence. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18(3):20. doi: 10.18332/tid/119324.

-

Xie J, Zhong R, Wang W, et al. COVID-19 and Smoking: What Evidence

Needs Our Attention?. Front Physiol. 2021;12:603850. doi:10.3389/

fphys.2021.603850

-

Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking

history on the severity of Covid-19: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J

Med Virol. 2020;1-7. doi:10.1002/jmv.2588.

-

Eisenber SH, Eisenberg MJ. Smoking Cessation During the COVID-19

Epidemic. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2020; 22(9): 1664-1665. https://

doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntaa075

-

Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect:

correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull.

2003;129(2):270-304. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270

-

Elling JM, Crutzen R, Talhout R, et al. Tobacco smoking and smoking

cessation in times of COVID-19. Tobacco prevention & cessation. 2020; 6:39.

https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/122753

-

Goss S., Anthony K., Jamieson A, et al. Guidelines for Online Counselling

and Psychotherapy. Rugby: BACP. 2001.

-

Chester A, Glass GA. Online counselling: A descriptive analysis of therapy

services on the Internet. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. 2006;

34(2): 145-160. doi : 10.1080/03069880600583170

-

Wellman B. “An electronic group is virtually a social network.” Culture of

the Internet. 1997;4:179-205.

-

Reese RJ, Conoley CW, Brossart DF. The Attractiveness of Telephone

Counseling: An Empirical Investigation of Client Perceptions. Journal of

Counseling & Development. 2006; (84):54-60.

-

Montgomery S and Papadakis S. Remote consultations: Delivering

behavioural support and supply of NRT. 2020 National Centre for Smoking

Cessation and Training About the National Centre for Smoking Cessation.

https://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pub/Remote%20consultations.pdf

-

Praslova L. Adaptation of Kirkpatrick’s four level model of training criteria

to assessment of learning outcomes and program evaluation in Higher

Education. Educ Asse Eval Acc. 2012;22:15–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s11092-010-90987

-

An LC, Zhu SH, Nelson DB, et al. Benefits of Telephone Care Over Primary

Care for Smoking Cessation A Randomized Trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;

166:536-542.

-

Lichtenstein E, Glasgow RE. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation:

rationales and meta-analytic review of evidence. Health Education and

Research Theory & Practice. 1996; 11(2): 243-257.

-

Macleod ZR, Arnaldi VC, Adams IM, et al. Telephone counselling as an

adjunct to nicotine patches in smoking cessation: a randomized controlled

trial. Medical Journal of Australia. 2003;179(7):349–352. doi:10.5694/

j.13265377.2003.tb05590

-

Cunningham JA, Kushnir V, Selby P, et al. Effect of Mailing Nicotine

Patches on Tobacco Cessation Among Adult Smokers. A Randomized

Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):184-190. doi:10.1001/

jamainternmed.2015.7792

-

Mermelstein R, Hedeker D, Wong SC, et al. Extended telephone counseling

for smoking cessation: Does content matter? Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology. 2003; 71: 565–574.

-

Lynch DJ, Tamburrino MB, Nagel R, et al. Telephone counseling for patients

with minor depression: Preliminary findings in a family practice setting. The

Journal of Family Practice. 1997;44;293–298.

-

Reno JP. Managing for Service Effectiveness in Social Welfare

Organizations. Social work. 1987;32(5):377–381. https://doi.org/10.1093/

sw/32.5.377

-

Vanclay F, Esteves AN, Aucamp I, et al. Social Impact Assessment:

Guidance for assessing and managing the social impacts of projects.

International Association for Impact Assessment. 2015.

-

Lee EKM, Lee H, Kee CH, et al. Social Impact Measurement in Incremental

Social Innovation. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. 2019;12(1):69-86.

doi: 10.1080/19420676.2019.1668830

-

SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification

of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149-159.

Raymond KS Ho,

MRCP (UK), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKAM (Medicine)

Medical officer,

Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation

Helen CH Chan,

BSW, M.Soc.Sc. MPH

Supervisor,

Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation

Grace NT Wong,

RSW, BSW

Counsellor,

Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation

Patrick WY Fok,

RSW, BSW

Assistant Supervisor,

Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, Integrated Centre on Smoking Cessation

Correspondence to:

Dr. Raymond KS Ho, 10/F Tung Chiu Commercial Centre,

193-197 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: kinsang.ho@tungwah.org.hk

|