Recognising familial hyperlipidaemia in

adult patients in primary care

Dorcas Yan 甄多嘉, Kwai-sheung Wong 黃桂嫦, Catherine XR Chen 陳曉瑞

HK Pract 2023;45:97-101

Summary

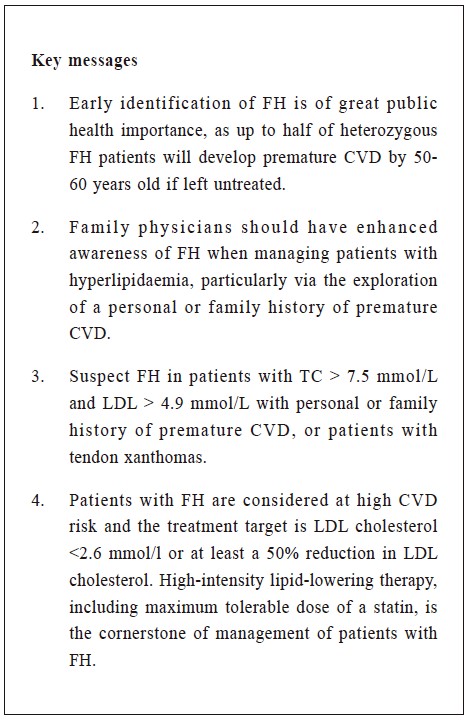

Despite being one of the most common genetic

disorders, familial hyperlipidaemia (FH) remains

underdiagnosed both locally and internationally. Due

to its drastic consequences such as fatal premature

cardiovascular events, timely recognition and

management of FH may significantly improve the

clinical outcomes of patients with FH.

As the first contact and gate keeper of the

healthcare system, family physicians need to have

enhanced awareness of FH when managing patients

with hyperlipidaemia, and offer intensive interventions

to reduce the patients’ cardiovascular risk.

摘要

家族性高膽固醇血症是臨床上最常見的遺傳病之一,

但在本地和國際上的關注不多,以致很多個案未被明確診

斷出來。家族性高膽固醇血症可導致致命性心血管疾病等

嚴重後果,而及時診斷和治療本病可明顯改善病人的臨床

成效。作為醫療系統的守門人,家庭醫生需要提升對此病

的關注,及時診斷並提供積極有效的治療,以減低病人患

心血管疾病的風險。

The Case

We report here a case of familial hyperlipidaemia.

Our patient, Ms. Chung (not her real name), was

75-year-old in 2021; and she had been attending at our

government primary care clinics for many years. She

had had hypertension, primary hypothyroidism and

hyperlipidaemia since 2018. Her medications included

Rosuvastatin 20 mg daily, Amlodipine 7.5 mg daily,

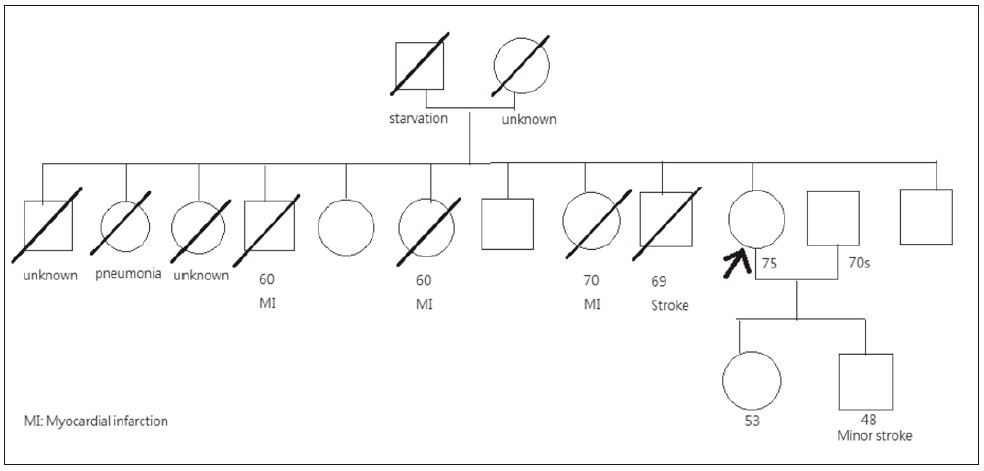

and Thyroxine 25 mcg daily. She had a strong family

history of cardiovascular diseases (CVD), with 4 out

of her 12 siblings being affected either by myocardial

infarction or stroke. Also, her son suffered from a minor

stroke in his 40s (Figure 1).

Ms. Chung is still attending our follow-up clinic

at the moment. However, she was seen in our General

Outpatient Clinic (GOPC) of the Hospital Authority in

August, 2021 for skin nodules for 3 months. The skin

nodules first appeared on her elbows on both sides,

which then extended to her forearms, knees and down to

her feet dorsum. The nodules were not associated with

pain or itchiness. There was no skin rash, joint pain, or

fever, neither history of gout nor rheumatoid arthritis.

There was no recent special contact history and she

had not taken any herbal medicine or drugs from over

the counter. Her blood pressure had been satisfactorily

controlled all along with good drug compliance. Up

till now, she has no chest pain or shortness of breath,

and has maintained a healthy diet and lifestyle. She has

never smoked nor consumed alcohol.

In 2021, her general condition had been good.

Physical examination was satisfactory. Her clinic blood

pressure (BP) was 128 / 76 mmHg, pulse 76 beats per

minute, and she was not obese clinically.

There were crops of erythematous papules over the

extensor surfaces of both her forearms and knuckles,

sparing the palmar crease (Figure 2). There was no

arcus cornealis or xanthelasmas. At the time of her

visit, clinically she was euthyroid.

Figure 1:

Family tree of Ms. Chung

Figure 2:

Picture of the skin lesion (with the kind

permission of Ms. Chung). There were crops of

erythematous papules over the extensor surfaces

of both forearms, which were consistent with

the diagnosis of tendon xanthomas.

Lipid profile done in June, 2018 when she was first

diagnosed with hyperlipidaemia was: total cholesterol

(TC) 8.5 mmol/L, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) 1.5

mmol/L, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) 6.2 mmol/L,

and triglycerides (TG) was 1.7 mmol/L. Her liver, renal,

thyroid function tests and fasting sugar level were all

normal. She was advised to have lifestyle modifications

and Rosuvastatin 20 mg was prescribed for the lipid

control. Blood tests in July, 2021 showed that TC was

down to 6.6 mmol/L, HDL was 1.6 mmol/L, LDL was

4.5 mmol/L, and TG was 1.1 mmol/L. Annual ECG

examination showed normal sinus rhythm without

ischemic changes.

In light of the strong family history of CVD, the

typical physical examination findings and the very

high LDL level, the most likely diagnosis of the skin

nodules for this lady was cutaneous xanthomas due

to her underlying disease of familial hyperlipidaemia

(FH). Hence, Rosuvastatin dose was stepped up to 40

mg daily, and the patient was reinforced on lifestyle

modifications.

Year 2021

Her lipid profile in November, 2021 showed that

TC was 5.0 mmol/L, HDL was 1.6 mmol/L, LDL was

3.0 mmol/L, and TG was 1.1 mmol/L. As the LDL level

remained suboptimal, self-financed Ezetimibe (FDAapproved

in 2002) 10 mg daily was added on top of

Rosuvastatin to intensify the LDL control. Her latest

blood tests in March, 2022 showed a satisfactory lipid

control with TC 3.6 mmol/L, HDL 1.7 mmol/L, LDL

1.4 mmol/L, and TG 0.9 mmol/L. Ms. Chung was

arranged to have continued follow up (FU) with regular

monitoring of the lipid profile.

Discussion

Heterozygous familial hyperlipidaemia (HeFH)

is one of the most common genetic disorders in the

general population across the world, with a prevalence

ranging from 1: 200 to 1:311.1,2 The prevalence of

HeFH in Hong Kong remains unknown, but large population studies from mainland China using the

Chinese modified Dutch Lipid Clinic Network (DLCN)

definition revealed that the crude prevalence of HeFH

was 0.28% to 0.35%3,4, which is slightly lower than

that of the western population. HeFH is an autosomal

dominant condition caused by genetic mutations

related to the LDL receptor pathway, with high levels

of LDL leading to the premature development of

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. If left untreated,

men and women with HeFH typically develop coronary

heart disease before the ages of 55 and 60 years,

respectively; 50% of men and 15% of women die

before these ages.5,6 Despite its prevalence and potential

severe consequences, FH remains underdiagnosed and

undertreated globally.6,7 Therefore, concerted efforts

among all health care workers, particularly in primary

care, should be made to enhance the awareness of FH.

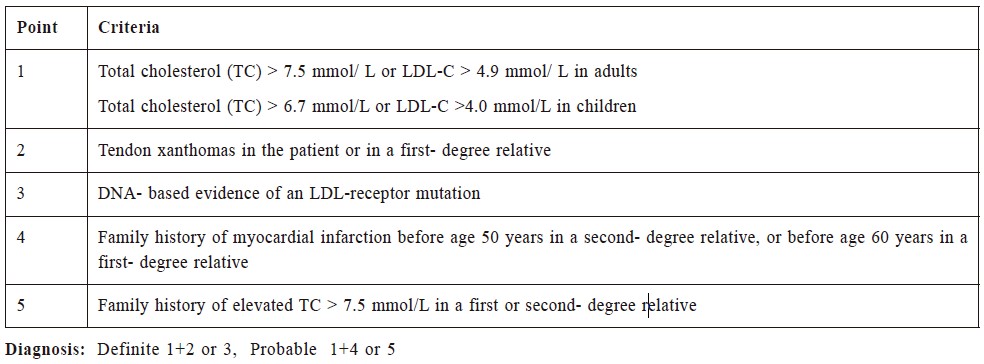

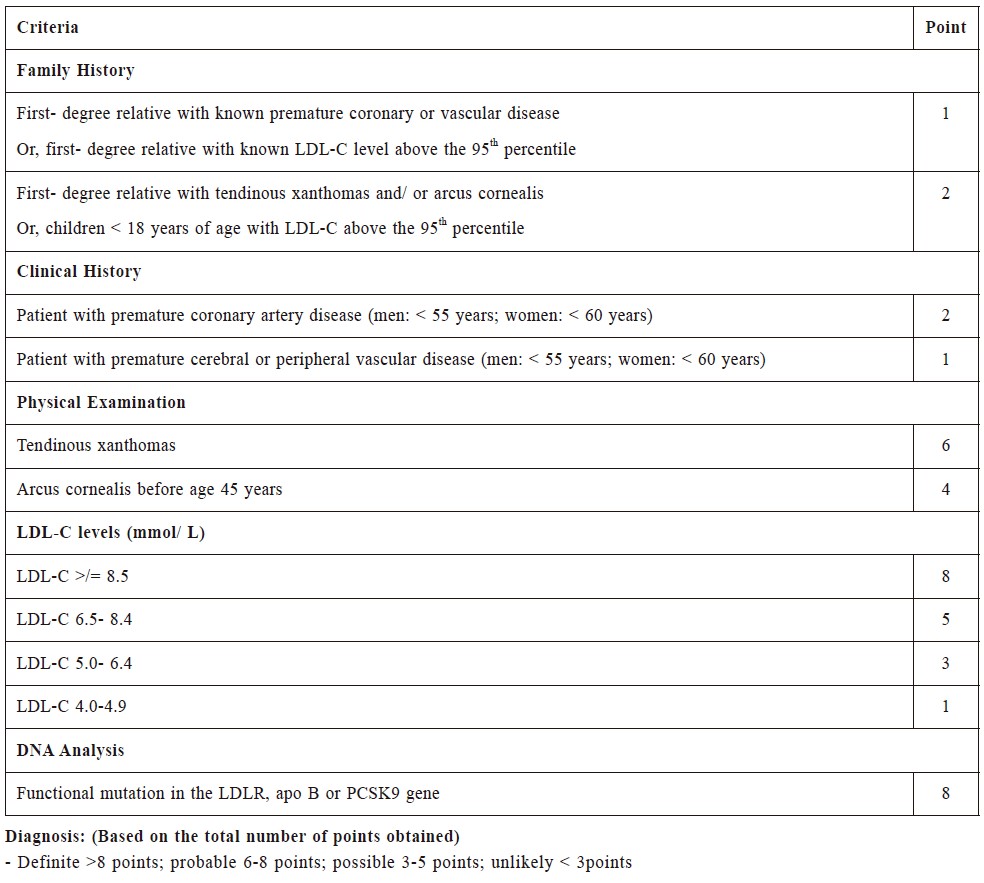

A number of diagnostic criteria for FH have been

reported in the literature, such as the Simon Broome

Register Diagnostic Criteria and the DLCN Diagnostic

Criteria (Table 1 & 2).8,9 There is no consensus on

which set of criteria is superior than the other. The

diagnosis of FH mainly takes into account the patient's

personal history, family history, clinical signs such as

tendon xanthomas and arcus cornealis, as well as the

much elevated LDL levels.10

Tendon xanthomas are white or yellow cholesterol

deposits over the extensor tendons, typically the

Achilles, subpatellar and hand extensor tendons.

They are considered pathognomonic and specific

for the diagnosis of FH.10,11 Secondary causes of

hyperlipidaemia including hypothyroidism, nephrotic

syndrome, obstructive liver diseases, steroid use, and

excessive alcohol intake should be ruled out before the

diagnosis of FH is established.12

In general, physicians should consider the

possibility of FH in patients with premature coronary

events and whose TC is over 7.5 mmol/L, or LDL is

over 4.9 mmol/L.2,9,12

Local guideline recommend a lower LDL

threshold- the possibility of FH should be considered

in patients with family or personal history of premature

coronary events and LDL > 4.5 mmol/L.11 Our patient

Ms. Chung fulfilled the Simon Broome Register

Diagnostic Criteria of definite FH based on her strong

family history of CVD, in particular two of her siblings

dying of myocardial infarction at 60 years old, the presence of tendon xanthomas over her forearms, as

well as her sky-high TC and LDL level (8.5 mmol/

L and 6.2 mmol/L respectively) before treatment.

She also fulfilled the DLCN Diagnostic Criteria of

definite FH with a total score of 10. The otherwise

normal laboratory findings excluded the possibility of a

secondary cause accountable for her hyperlipidaemia.

Diagnosis of FH is often made based on the clinical

information and the laboratory findings. Although

genetic testing is usually not needed, a positive

genetic test with FH gene mutation is associated with

a significantly higher cardiac risk.10 Locally, genetic

testing is available at Clinical Genetic Service of

the Department of Health11 or in advanced private

diagnostic centers. CVD risk assessment tools such as

those based on the Framingham algorithm should not be

used for people with FH. This is particularly important

to note for healthcare professionals in the primary care

setting as patients with FH are already considered as

having a high risk of developing CVD.

Multiple factors modify the risk of HeFH, such

as male sex, smoking, presence of diabetes mellitus,

hypertension, subclinical coronary atherosclerosis, lower

HDL and higher lipoprotein(a) levels.13 Our patient Ms.

Chung has not been diagnosed to have HeFH until she

is 75 years old and fortunately she has not suffered

from a CVD attack until this moment. Female gender,

well controlled BP, her healthy lifestyle and lack of

other CVD risk factors such as smoking or diabetes

mellitus might have helped to reduce her overall CVD

risk. Indeed, HeFH is easily missed or underdiagnosed

in primary care. All family physicians are advised

to enlist HeFH as one of the differential diagnoses

whenever a dyslipidaemia patient is encountered.

Timely and effective lipid control improves the life

expectancy of patients with FH. The management of

FH consists of counselling, family screening, lifestyle

advice, treatment of CVD risk factors and intensive

lipid-lowering therapy starting early in life. Physicians

could counsel patients regarding the implications and

mode of inheritance of FH. Family screening should

be offered as half of the patient’s first-degree relatives

could be affected.5 Screening can be done by measuring

the LDL levels, carrying out genetic analyses, or both.7,8

Apart from counselling and family screening, physicians

should promote positive lifestyle changes, advocating

for healthy diet, regular exercises, weight reduction, and

Table 1:

Simon Broome Diagnostic Criteria for familial hypercholesterolemia.

Table 2:

Dutch Lipid Clinic Network Diagnostic Criteria for familial hypercholesterolemia

smoking cessation if the patient smokes.9 High-intensity

lipid-lowering therapy, such as maximum tolerable

dose of statin, is the cornerstone of FH management.

Ezetimibe is considered as second line treatment if

LDL fails to be adequately controlled by statin alone9,11,

and bile acid sequestrants or niacin are considered

as third line choices.7 If these agents are exhausted,

patients could be referred to specialists for considering

proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9)

inhibitors treatment.11,12

With regard to the target of LDL control, most

guidelines recommend a LDL target of below 2.6 mmol/

L, or at least a 50 % reduction in LDL cholesterol for

the primary prevention of CVD.7 A LDL target of below

1.8 mmol/L is used for secondary prevention in patients with established CVD.11 Australian and European

Society of Cardiology guidelines suggest a stricter

target of LDL < 1.4 mmol/L for patients with clinical

evidence of atherosclerotic CVD.7,12

For our patient Ms. Chung, her LDL level of 4.5

mmol/L in July, 2021 was apparently not adequately

controlled and therefore Rosuvastatin dose was stepped

up. After the dose augmentation, her LDL level had

improved, though remained suboptimal. To further

reduce her CVD risk, Ezetimibe was added on top of

the statin treatment, which successfully brought her

LDL level down to target. Ms Chung’s clinical condition

will be regularly reviewed and her lipid profile will be

closely monitored in future FUs.

Referencess

-

Hu P, Dharmayat KI, Stevens CAT, et al. Prevalence of familial

hypercholesterolemia among the general population and patients with

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and metaanalysis.

Circulation. 2020;141(22):1742–1759.

-

Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the

management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular

risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111–188.

-

Wang Y, Li Y, Liu X, et al. The prevalence and related factors of familial

hypercholesterolemia in rural population of China using Chinese modified

Dutch Lipid Clinic Network definition. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):837.

-

Shi Z, Yuan B, Zhao D, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia in China:

prevalence and evidence of underdetection and undertreatment in a

community population. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(3):834–836.

-

Brett T, Arnold-Reed D. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: A guide for general

practice. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(9):650–652.

-

Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Humphries SE, et al. Familial

hypercholesterolaemia is underdiagnosed and undertreated in the general

population: guidance for clinicians to prevent coronary heart disease:

consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur Heart J.

2013;34(45):3478–3490a.

-

Lui DTW, Lee ACH, Tan KCB. Management of familial hypercholesterolemia:

Current status and future perspectives. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(1):bvaa122.

-

Tan K, Cheung CL, Yeung CY, et al. Genetic screening for familial

hypercholesterolaemia in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2018;24 Suppl

3(3):7–10.

-

Recommendations. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: identification and

management. Guidance. NICE. [cited 2021 Dec 26]; Available from:

http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg71/chapter/Recommendations

-

McGowan MP, Hosseini Dehkordi SH, Moriarty PM, et al. Diagnosis and

treatment of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. J Am Heart Assoc.

2019;8(24):e013225.

-

Tomlinson B, Chan JC, Chan WB, et al. Guidance on the management of

familial hypercholesterolaemia in Hong Kong: an expert panel consensus

viewpoint. Hong Kong Med J. 2018;24(4):408–415.

-

Brett T, Radford J, Heal C, et al. Implications of new clinical practice

guidance on familial hypercholesterolaemia for Australian general

practitioners. Aust J Gen Pract. 2021;50(9):616–621.

-

Rocha VZ, Santos RD. Past, present, and future of familial hypercholesterolemia

management. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2021;17(4):28–35.

Dorcas Yan,

MBBS (HK)

Resident,

Dept. of FM and GOPCs, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority

Kwai-sheung Wong,

MBBS (HK), FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Associate Consultant,

Dept. of FM and GOPCs, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority

Catherine XR Chen,

LMCHK, PhD (Med, HKU), MRCP (UK), FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Consultant,

Dept. of FM and GOPCs, Kowloon Central Cluster, Hospital Authority

Correspondence to: Dr. Dorcas Yan, Room 807, Block S, Queen Elizabeth Hospital,

30 Gascoigne Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: yd902@ha.org.hk

|