Utilisation rate of non-vitamin K antagonist oral

anticoagulant, and associated factors of refusal

of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant

usage in atrial fibrillation patients - A study

in two Hong Kong general out-patient clinics

Liujing Chen 陳柳靜, Chik-pui Lee 李植沛, Lit-ping Chan 陳列萍, Eric MT Hui 許明通, Maria KW Leung 梁堃華

HK Pract 2023;45:89-96

Summary

Objective:

To evaluate the utilisation rate of non-vitamin

K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) and associated

factors of NOAC refusal in atrial fibrillation (AF) patients.

Design:

A cross-sectional study.

Subjects:

All the AF patients, who were regularly

followed up in two public general out-patient clinics

(GOPC) from November 2019 to March 2020, aged

older than 18 years, and eligible for NOACs.

Main outcome Measures:

Utilisation rate of NOAC in

AF patients. The associated factors of NOAC refusal in

AF patients.

Results:

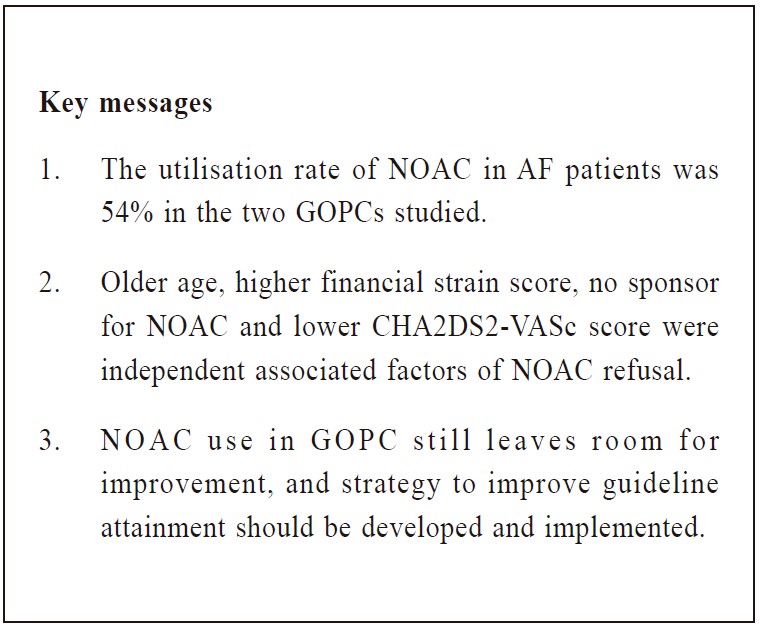

A total of 324 patients were included during

the study period. Utilisation rate of NOAC in AF patients

was 54%. Multivariate analysis revealed that older age,

higher financial strain score, lack of sponsor for NOAC

and lower CHA2DS2-VASc score were the factors

that were significantly associated with NOAC refusal.

Conclusion:

In our study, the utilisation rate of NOAC in

AF patients in the two local GOPCs studied was 54%,

which implied there was still room for improvement.

The associated factors of NOAC refusal highlighted

the importance of financial support to promote the

usage of the NOAC. Further research and strategy

to improve guideline attainment should focus on the

subgroup patients who were older and who had a lower

CHA2DS2-VASc score.

Keywords:

Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, non-vitamin

K antagonist oral anticoagulant, Hong Kong,

primary care

摘要

目的 :

評估非維他命K拮抗劑類口服抗凝血劑(NOAC)在心

房纖顫(AF)患者中的使用率,並且分析患者拒絕此藥的相關

因素 。

設計 :

橫斷面研究。

對象 :

2019年11月至2020年3月於兩間普通科門診常規複診

的AF成年患者,並且符合NOAC使用指徵。

主要測量內容 :

NOAC在AF患者中的使用率,以及患者拒

絕此藥的相關因素。

結果 :

共324位患者加入研究。NOAC在AF患者中的使用

率為54%。多因素分析結果顯示年老、高財務壓力評分、

NOAC缺乏資助、以及CHA2DS2-VASc低分是拒絕NOAC的

相關因素。

結論 :

本研究顯示,NOAC於兩間本地普通科門診AF患者

中的使用率為54%,仍然有待提高。相關因素分析顯示:

資助NOAC對於提高其使用率相當重要;對於年老以及

CHA2DS2-VASc分數低的患者,仍然需要進一步的分層分

析,尋找提高他們使用NOAC的途徑。

關鍵詞 :

心房纖顫,抗凝血劑,非維他命K拮抗劑類口服

抗凝血劑,香港,基層醫療

Introduction

Background and objectives

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac

arrhythmia1, with a lifetime prevalence of one fourth of

patients >40 years old.2 In a Hong Kong territory-wide

community-based AF screening programme, the prevalence

of AF detected by smartphone-based wireless single-lead

ECG or self-reported by participants was 8.5%.3

Individuals with AF have an increased risk of

stroke, and account for up to 1 of 3 stroke cases among

the elderly4,5, potentially leading to permanent disability

and death.6 Thus, stroke prevention in AF patients is an

urgent healthcare and public-health concern.

Anticoagulant is the most important modifiable

factor to reduce stroke incidence in AF.7 An old

drug used to reduce stroke incidence, Warfarin, is a

long-established anticoagulant.8 However, since the

introduction of the non-vitamin K antagonist oral

anticoagulant (NOAC) in the 2010s, these new drugs

have changed the landscape for stroke prevention in

AF patients. Dabigatran was the first NOAC on the

market which was approved for stroke prevention in

patients with non-valvular AF by the US Food and Drug

Administration in 2010. Since then, 3 other NOACs

(rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban) are available in

many countries worldwide, including Hong Kong. Of

the 3, edoxaban, which was the last of them, became

registered in the Hong Kong Drug Office in 2016.

NOACs are not inferior to warfarin when used

for stroke prevention9,10, and some analyses of clinical

effectiveness suggests that they are actually preferable.11

NOACs are indicated to prevent stroke in patients

with non-valvular AF by both the European Society of

Cardiology (ESC) and the American Heart Association

(AHA) guidelines for patients with CHA2DS2-VASc

Score ≥1 in male, and ≥2 in female.1,12,13

However, there is still a great gap between

guidelines and the clinical utilisation rate of NOACs.

A nationwide study in Korea found that NOAC use

increased from 0% in 2002 to 14.% in 2016 in AF

patients.14 A Taiwan study of 181214 newly diagnosed

AF patients revealed that the NOAC use increased from

0% in 2008 to 26.0% in 2015.15

In order to promote the usage of the NOACs in AF

patients, dabigatran and apixaban were introduced into

our general out-patient clinics (GOPCs) of the Hospital

Authority (HA) in mid 2019. The prescription of these

NOACs was limited to patients with a high risk of

stroke whose CHA2DS2-VASc score was 5 or more. In

actuality, a number of AF patients still refused NOACs,

even through they are eligible for its use. Is this refusal

related to the problem of patient affordability? What is

the utilisation rate of NOAC in the GOPC setting?

So far, there is no study on the utilisation rate of

NOAC in the GOPC setting and no local data on the

associated factors for NOAC refusal. Therefore, this

study was conducted to evaluate the utilisation rate of

NOAC, and the factors independently associated with

NOAC refusal in AF patients, aiming at locating the

barriers to optimal NOAC use in the GOPC setting.

Method

Design and setting of the study

This was a cross-sectional study. A quantitative

method was selected because this approach can

objectively reflect the facts.

This study was conducted in two GOPCs in Tai

Po, with ethics approval by the Local Ethics Committee

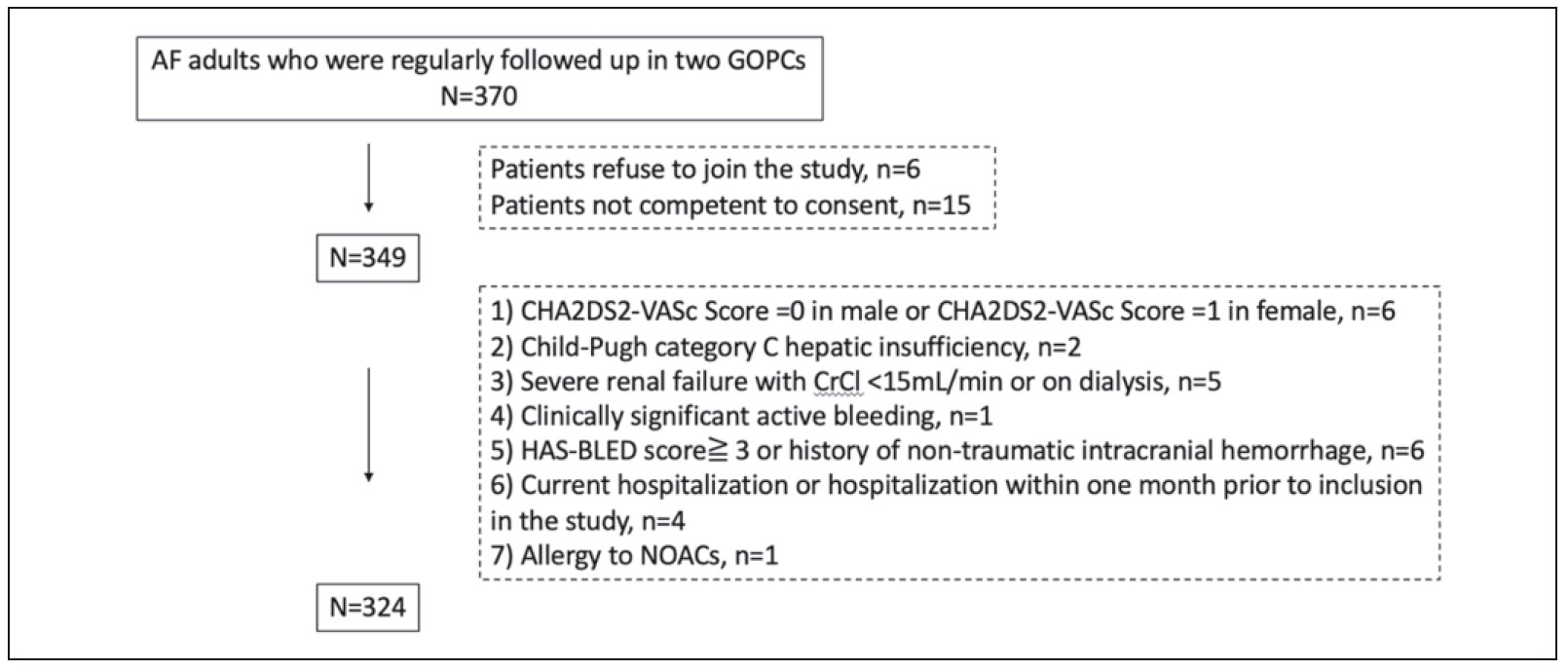

(CREC Ref. No. 2019.516). The flowchart in

Figure

1

illustrated the patients’ enrolment in the study. A list

of patients with International Classification of Primary

Care (ICPC) coding of AF(K78) was retrieved from the

Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS)

of HA. All AF patients who were regularly followed up

in participating clinics were invited to attend the

Atrial

Fibrillation Clinic

(AFC). Patients aged older than 18

years were recruited during initial visit in November

2019 to December 2019. A follow-up visit was arranged

3 months after initial visit to review their option of

NOAC use and compliance. Study subjects were seen by

the principal investigator in the AFC, with active review

of the clinical condition and discussion of the NOACs

options. The suggestions of NOACs followed stroke

prevention guidelines recommended by the European

Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2016 and the American

Heart Association (AHA) 2014 and 2019.1,7,13 Patients

on warfarin were mainly followed up in Specialist Outpatient

Clinics (SOPDs). Hence, we do not initiate

warfarin in our GOPCs. Informed consent was also

obtained from the study subjects before enrolment into

the study.

Figure 1:

Flowchart of patients enrolled in the study

Patient selection

Patients having one or more of the following were

excluded:

(i) Males with CHA2DS2-VASc Score = 0, and

females with CHA2DS2-VASc Score = 1

(ii) Patients with moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis

(iii) Prosthetic valve or valve repair

(iv) Child-Pugh category C hepatic insufficiency.

(v) Severe renal failure with CrCl < 15mL/min or on dialysis

(vi) Clinically significant active bleeding

(vii) HAS-BLED score16 ≧ 3 or history of non-traumatic

intracranial haemorrhage

(viii) Pregnancy or breastfeeding mother

(ix) All Current hospitalisation or hospitalisation

within one month prior to inclusion in the study.

(x) Allergy to NOACs

(xi) Those who refuse to join the study, or not competent

to consent

Data collection

Baseline demographic and clinical data was

collected and recorded via a questionnaire and a review

of the medical records in the Hospital Authority’s

Clinical Management System (CMS).

The following data were collected (1)

sociodemographic information including age, sex,

education level, living condition, marital status,

financial strain, employment status; (2) drinking and

smoking habit; (3) any sponsor for NOACs; (4) duration

of atrial fibrillation; (5) CHA2DS2-VASc component

details; (6) NOAC use.

Financial strain data was collected instead of

income as it was a more powerful control variable than

income.17 The measure of financial strain was based

on four items: three items asked respondents whether

they had enough money to pay for their needs in food,

in medical services, and daily expenses, using a three-point

scale ranging from 1 = enough, to 3 = not enough.

The fourth question asked respondents to rate how

difficult it was for them to pay their monthly bill using

a four point scale, ranging from 1 = not difficult at all,

to 4 = very difficult. A sum of the scores of these four

items was computed, yielding a range from 4-13, with

high scores indicating greater strain.18

Drinker was defined as more than 7 units (for

women) or 14 units (for men) of alcohol in a week.

Smoker was defined as active smoking or smoking

cessation less than 1 year.

Sponsor for NOAC was defined as (a) CHA2DS2-

VASc score ≧5 hence no extra charge for NOAC in

GOPC, or (b) Civil service eligible persons with full

reimbursement of NOAC, or (c) Full reimbursement of

NOAC by insurance.

CHA2DS2-VASc score was calculated according

to the AHA guideline13: congestive heart failure,

hypertension, age ≥75 years (doubled), diabetes

mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism (doubled), vascular disease, age 65 to

74 years, sex category, with theoretical score range 0–9.

Outcome variable

NOAC refusal group was defined as patient

refusing to take any NOAC during the consultation in

follow up visit. NOAC non-refusal group was defined

as those who used NOAC for at least 3 months and was

willing to continue NOAC during follow up visit.

NOAC refusal group was coded as “1 = refuse” and

“0 = not refuse” for the logistic model.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 24.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) was

used for analysis of data. Continuous data are presented

as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical data are

shown as number and percentage. Chi-square test was

used to compare categorical variables. For continuous

variables, independent T-test was used for comparing two

groups. Data was compared between the NOAC refusal

group and non-refusal group. Binary logistic regression

analysis was performed to identify factors significantly

associated with the refusal of NOACs. Adequate subject

number was based on 10 events per variable (EPV) in

logistic regression analysis.19 A P-value of less than 0.05

was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

(A) Study population

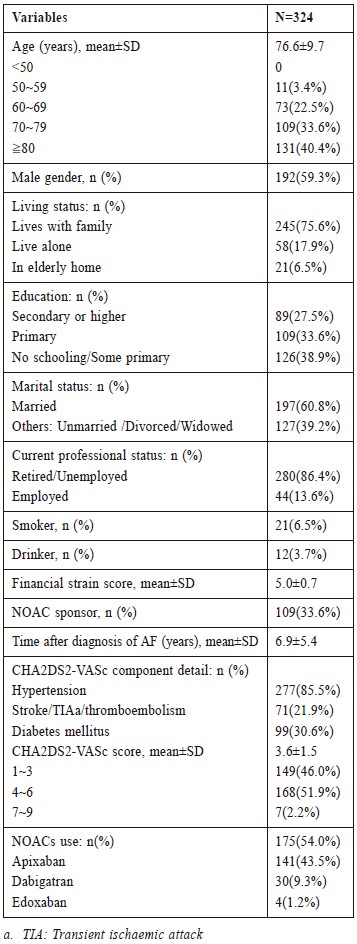

A total of 324 AF patients from two GOPCs

were recruited. Average age was 76.6±9.7 years, and

192(59.3%) were male. Baseline demographic data,

clinical characteristics, and use of NOACs are shown in

Table 1. Among recruited patients, no one was younger

than 50 years old. The majority of patients (96.6%)

were older than 60 years old and most of the patients

had primary school education or below. 215(66.4%)

patients had no sponsor for NOACs. 109(33.6%)

patients had sponsor for NOACs and 21 patients among

them refused NOACs use. 277 patients (85.5%) had a

history of hypertension while 99(30.6%) patients had a

history of diabetes mellitus. Average CHA2DS2-VASc

score was 3.6±1.5 in this population.

(B) Utilisation rate of NOAC

Usage of NOACs were by 175(54.0%) patients.

Apixaban was 141 patients, (80.6% of all NOAC user)

(Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

of the study population, and NOAC taken by the

study population.

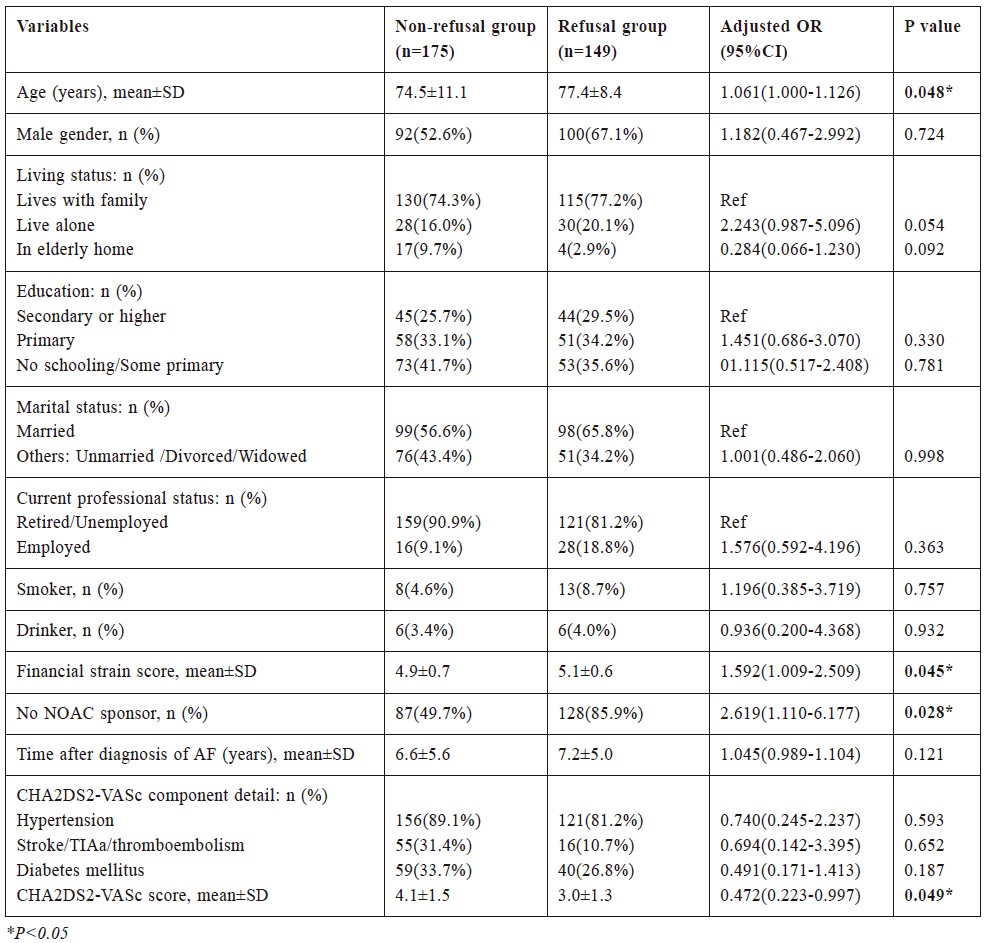

(C) Associated factors of NOAC refusal

Comparisons of data between NOAC refusal group

and non-refusal group were shown in Table 2.

Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis

revealed that older age (Adjusted OR 1.061, CI 1.000-

1.126, P=0.048), higher financial strain score (Adjusted

OR 1.592, CI 1.009-2.509, P=0.045), no sponsor for

NOAC (Adjusted OR 2.619, CI 1.110-6.177, P=0.028)

and lower CHA2DS2-VASc score (Adjusted OR 0.472,

CI 0.223-0.997, P=0.049) were independent associated

factors for NOAC refusal in AF adults.

Discussion

This study was conducted in AF patients who were

regularly followed-up in two GOPCs in Hong Kong.

All of the recruited patients were eligible for the use of

NOACs. The utilisation rate of NOAC in this population

was 54%, with room for improvement.

Overseas studies showed great disparity of NOAC

utilisation rate according to study time, region, and

type of institute. A Taiwan study with 181,214 newly

diagnosed AF patients revealed that the NOAC use

increased from 0% in 2008 to 26.0% in 2015.15 A study of 888,540 AF patients in Korea found that the

usage rate of NOAC was significantly different among

different medical systems from 37.2% at the tertiary

referral hospital and 5.5% at nursing or public health

centers.14 Another nationwide study in Korea showed

the proportions of prescribed NOACs to total oral

anticoagulants were 5.1%, 36.2%, and 60.8% in 2014,

2015, and 2016, respectively.20 A primary care study

in UK between June 2012 and June 2014 revealed

that 53% AF patients who were not on anticoagulation

agreed to start NOAC.21

Table 2:

Binary logistic regression analysis for factors associated with refusal of NOAC in AF patients

It was difficult to directly compare our NOAC

utilisation rate with previous studies as some of

them included warfarinised cases in their study

population14,15,21 and some of them aimed to analyse

the NOAC utilisation rate among all the anticoagulant

users.20 We could calculate the NOAC utilisation rate in

AF patients according to the data of the Taiwan study

to be 28.8% in 201515, which was lower than our data.

However, our data collection started in 2019 and a

higher utilisation rate was not surprising. Overall, this

study and overseas studies showed that there was still a

great gap between guidelines and the clinical utilisation

rate of NOAC.

Another aim of this study was intended to identify the

associated factors of NOAC refusal in the GOPC setting.

Our result showed that the lack of NOAC sponsor

and higher financial strain score were significantly

associated with NOAC refusal. NOACs were introduced

to GOPC in Hong Kong by the Hospital Authority in

mid 2019. However, the prescription was only limited

to patients with a high risk of stroke whose CHA2DS2-

VASc scores were 5 or above. Eligible patients can

be prescribed NOACs in the GOPCs without extra

cost after consultation. The non-eligible patients can

purchase NOACs in the community pharmacy with

a prescription issued by the GOPC doctor (they had

to pay HK$600 to HK$1500 per month according to

the type of NOAC and dosage). Obviously, for these

patients whose CHA2DS2-VAS2 scores were below 5,

affordability had a direct impact on their NOAC use,

and our findings shared similarities with other studies.

The previous studies demonstrated how health

policy and insurance influenced the use of NOACs.

In Korea, the policy of health insurance coverage for

NOACs was revised in July 2015 to allow a broader

coverage, and a study showed a significant growth

rate of NOAC prescription after this was introduced.20

Another nationwide study in Korea about newly

diagnosed AF patient revealed that partial and full

reimbursement of NOAC were independently associated

with higher anticoagulant use.14 There was a study on

associated factors for anticoagulants (including NOAC

and warfarin) use in 593 non-valvular atrial fibrillation

patients in China Jiangsu province, which showed self-paying

was negatively associated with anticoagulant

therapy in all patients.22

Based on the result of our study, a broader

sponsorship for NOACs in primary care was suggested

for the purpose of promoting the usage of NOAC.

Nevertheless, we also noticed in the group of 109

patients who were eligible for NOAC sponsorship,

21 patients (19.3%) still refused NOAC use, which

meant that patient affordability was not the only factor

associated with NOAC refusal. Unfortunately, a sample

size of 21 patients would not be sufficient to support

further quantitative analysis. Further research involving

a bigger sample size in this subgroup of patients would

be helpful to identify the barriers of NOAC use apart

from the money issue.

A previous study about NOAC adherence showed

education level and information about the disease could

affect the medication use.23 In our study, however,

patient’s education level was not related to NOAC

refusal based on the results of the multivariable analysis.

One of the possible explanations was that the patient’s

education level might not be equal to their knowledge

level which potentially influenced the decision of NOAC

use. Furthermore, the education level was difficult to be

graded in the elderly (mean age of our study subjects

was 76.6 years old) as most of them did not receive

formal education. Still, one had to bear in mind that

a multitude of factors besides the knowledge level of

patients potentially influenced the choice of medication.

Patients’ perspectives, perceptions and attitudes cannot

be well assessed in a quantitative study. Additional

qualitative research is needed to unravel and understand

these factors influencing NOAC use in patients.

Older age was an independent predictor of NOAC

refusal in our study. The elderly with AF, especially

those aged ≥75 years, are considered to have at least

a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2.13 This population is

the group with the highest risk of stroke and the

worst prognosis, thus, oral anticoagulant is certainly

recommended. However, the data on the NOACs option

in the elderly was not sufficient in previous studies.

A small sample study among non-valvular AF patients

in China indicated that increasing age was negatively

associated with anticoagulant therapy (including NOAC

and warfarin).22 Plenty of studies about warfarin use in

the elderly showed that overestimation of the bleeding

risk and disadvantages associated with advanced age

are barriers to the prescription of oral anticoagulants

in the elderly.24 Therefore, the underutilisation of

NOAC in the elderly group might share similar reasons.

Other possible reasons include relatively lower mental

capacities to comprehend benefit and risk of NOAC

and difficulty to negotiate with family members before

decision making.

In general, the decision to prescribe NOAC in

the elderly is complicated. It requires not only to

balance the stroke risk and bleeding risk, but also

the need to consider the patient’s general health,

functional and cognitive ability, availability of a

caregiver, and patient’s attitude and preference towards

anticoagulation. More attention should be paid to this

group of elderly patients during consultation and setting

up of a special clinic with a multidisciplinary approach

to provide patient education, medication monitoring and

dosage adjustment might help.

Low CHA2DS2-VASc score was another associated

factor for NOAC refusal in our study. A study in

Thailand for AF patients aged ≥65 years showed

CHA2DS2-VASC score 1, to CHA2DS2-VASC score ≥2,

increases the rate of non-prescription of anticoagulant.25

However, the results of this study could not be compared

to our study which defined CHA2DS2-VASc score as

scale variable and excluded CHA2DS2-VASc Score

=0 in male or CHA2DS2-VASc Score =1 in female. A

Taiwanese study had similar results as our study. Patients

who were not on any antithrombotic therapy tended to

have lower CHA2DS2-VASc score (5.1±1.6) than those

taking antiplatelet agents (5.6±1.5) or warfarin (5.7±1.5).26

One explanation was that lower CHA2DS2-VASc score

implied lower risk of stroke and hence, lower cost

effectiveness of NOAC. However, the CHA2DS2-VASc

score could not predict the severity of stroke, whether

it’s major stroke or TIA. This study demonstrated a

barrier in initiating NOAC when patients have lower

CHA2DS2-VASc scores. This group of patients should

not be neglected, and methods of improving NOAC use

including educational programme should be put in place.

Strengths and limitations

There are strengths in this study. Firstly, this is the

first paper to quantify the use of NOACs in AF patients

in the Hong Kong GOPCs. There are important clinical

and policy implications. The use of NOACs in GOPCs

will become comparable and traceable. It also facilitates

policy holders in resource allocations and planning future

medical expenditures. Secondly, patient consultation was

conducted by the same principal investigator using the

same stroke prevention guideline throughout the study,

which could standardise the information that physicians

might deliver to patients.

However, there are several limitations in this study.

Firstly, study subjects were retrieved according to the

ICPC code, and there was a possibility of missing small

number of cases if the diagnosis of AF was not coded.

Secondly, this study lack generalisability as it was

carried out in two public primary care clinics. Warfarin

is another anticoagulant eligible for AF patients.

However, we do not keep warfarin patients in our GOPC

as they were mainly followed up in SOPD. Hence, there

was no warfarin user among our subjects. Finally, this

study just determined the associated factors but not

causative factors of NOAC refusal. Further research

is needed to identify major reasons of NOAC refusal,

and strategy to improve guideline attainment should be

developed and implemented.

Conclusion

With the increasing AF prevalence in our aging

population, it is important to identify the barriers of

NOAC use in AF patients. By employing a quantitative

design to investigate the NOAC utilisation rate, we

found that NOAC use in the two studied GOPC groups

of AF patients was 54%, which still leaves room for

improvement. This study identified four associated

factors of NOAC refusal: older age, higher financial

strain score, lack of sponsor for NOAC and lower

CHA2DS2-VASc score. The result highlighted the

importance of financial support to promote the usage

of the NOACs. Thus, future resources should be

focused on this high-risk group in order to reduce their

stroke risk and the subsequent financial burden due

to rehabilitation and hospitalisation. Further research

should focus on the subgroup of patients associated

with NOAC refusal, and strategy to improve guideline

attainment should be developed and implemented.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank our district

coordinator doctor and our clinic in-charge doctor

for their advice and supports on this study and the

AFC arrangement. Secondly, I would like to express

my wholehearted gratitude to the research committee

members for their valuable suggestion on my study

design. In addition, thanks all senior doctors in my clinic

for teaching me the proper writing of a research paper.

Funding/support

This research received no specific grant from any

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit

sectors.

Conflict of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

-

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for

the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice

guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

-

Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, et al. Lifetime risk for development

of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation.

2004;110(9):1042-1046.

-

Ngai-yin Chan, Chi-chung Choy. Screening for atrial fibrillation in 13122 Hong

Kong citizens with smartphone electrocardiogram. Heart 2017;103:24–31

-

Chien KL, Su TC, Hsu HC, et al. Atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence

and risk of stroke and all-cause death among Chinese. Int J Cardiol.

2010;139(2):173-180.

-

Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk

factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(8):983-988.

-

Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the

risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98(10):946-952.

-

Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the

management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS.

Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893-2962.

-

Ezekowitz MD, Bridgers SL, James KE, et al. Warfarin in the prevention

of stroke associated with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. Veterans Affairs

Stroke Prevention in Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. N Engl J

Med. 1992;327(20):1406-1412.

-

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in

nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883-891.

-

Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in

patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2093-2104.

-

Lopez-Lopez JA, Sterne JAC, Thom HHZ, et al. Oral anticoagulants for

prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation: systematic review, network metaanalysis,

and cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j5058.

-

Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm

Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist

oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J.

2018;39(16):1330-1393.

-

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused

Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management

of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical

Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol.

2019;74(1):104-132.

-

Yu HT, Yang PS, Hwang J, et al. Social Inequalities of Oral Anticoagulation

after the Introduction of Non-Vitamin K Antagonists in Patients with Atrial

Fibrillation. Korean Circ J. 2020;50(3):267-277.

-

Chao TF, Chiang CE, Lin YJ, et al. Evolving Changes of the Use of Oral

Anticoagulants and Outcomes in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Atrial

Fibrillation in Taiwan. Circulation. 2018;138(14):1485-1487.

-

Chiang CE, Okumura K, Zhang S, et al. 2017 consensus of the Asia Pacific

Heart Rhythm Society on stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Arrhythm.

2017;33(4):345-367.

-

MENDES DE LEON CF, RAPP, S.S. & KASL, S.V. Financial strain and

symptoms of depression in a community sample of elderly men and women.

Journal of Aging and Health. 1994;4:448-468.

-

Chou KL, Chi I. Financial strain and life satisfaction in Hong Kong elderly

Chinese: moderating effect of life management strategies including selection,

optimization, and compensation. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(2):172-177.

-

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number

of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol.

1996;49(12):1373-1379.

-

Ko YJ, Kim S, Park K, et al. Impact of the Health Insurance Coverage Policy

on Oral Anticoagulant Prescription among Patients with Atrial Fibrillation in

Korea from 2014 to 2016. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(23):e163.

-

Das M, Panter L, Wynn GJ, et al. Primary Care Atrial Fibrillation Service:

outcomes from consultant-led anticoagulation assessment clinics in the

primary care setting in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009267.

-

Liu T, Yang HL, Gu L, et al. Current status and factors influencing oral

anticoagulant therapy among patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

in Jiangsu province, China: a multi-center, cross-sectional study. BMC

Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):22.

-

Emren SV, Senoz O, Bilgin M, et al. Drug Adherence in Patients With

Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Taking Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral

Anticoagulants in Turkey: NOAC-TR. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost.

2018;24(3):525-531.

-

Wong CW. Anticoagulation for stroke prevention in elderly patients with

non-valvular atrial fibrillation: what are the obstacles? Hong Kong Med J.

2016;22(6):608-615.

-

Krittayaphong R, Phrommintikul A, Ngamjanyaporn P, et al. Rate of

anticoagulant use, and factors associated with not prescribing anticoagulant

in older Thai adults with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: A multicenter

registry. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019;16(3):242-250.

-

Chao TF, Liu CJ, Lin YJ, et al. Oral Anticoagulation in Very Elderly

Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Circulation.

2018;138(1):37-47.

Liujing Chen,

LMCHK, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Associate Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority

Chik-Pui Lee,

MBChB (CUHK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Associate Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority

Lit-Ping Chan,

MBBS (HK), FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Associate Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority

Eric MT Hui,

MBBS (HK), FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority

Maria KW Leung,

MBBS (Lond), FRACGP, FHKCFP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine, New Territories East Cluster, Hospital Authority

Correspondence to:

Dr. Liujing Chen, Lek Yuen General Out-patient Clinic, G/F,

9 Lek Yuen Street, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: cl802@ha.org.hk

|