Dental considerations in older adults attending

the primary care clinic

Katherine CM Leung 梁超敏

HK Pract 2023;45:105-111

Summary

Oral health is part of our general health. Older adults

attending the primary care medical clinic often require

dental care as well. Many of them present with dental

caries, periodontal diseases and tooth-loss due to

worsened physical health and other cumulative damage

brought by previous dental diseases.

The elderly patients may also be suffering from

systemic diseases and/or conditions which may have

direct impact on their dental conditions. This article

draws the attention of physicians, who are treating their

older patients, to major dental diseases as well as the

interactions between systemic diseases and/or other

medical conditions with their dental conditions.

Therefore, dental and medical professionals should work

closely together to provide collaborative patient care.

Keywords: Older adults, dental diseases, primary care

摘要

口腔健康是整體健康的一部分。尋求基層醫療的老年人通

常也需要牙科護理。由於身體健康變差和牙齒受先前的牙

患累積的破壞,他們大都患有齲齒( 蛀牙) 、牙周病和缺

牙。他們也可能患上一些可直接影響口腔健康的疾病。本

文提請治療老年人的醫生注意主要的牙齒疾病及其與身體

疾病的相互作用。牙醫和醫生應攜手合作給予病人全面的

照顧。

關鍵詞:老年人,牙齒疾病,基層醫療

Introduction

Oral health is part of our general health. Older

people receiving medical care often require dental

care as well. With increased dental awareness and

better access to dental care, the elderlies tend to retain

more teeth into their later years of life. However, the

dental condition of the older patients is often far from

satisfactory, due to their worsening physical conditions

and cumulative damage caused by dental diseases in

their past. Furthermore, degenerative changes, chronic

diseases and their treatments received can negatively

affect their oral health.

Two major dental diseases that cause eventual tooth

loss if left untreated are dental caries and periodontal

disease. Both diseases are to a large extent induced by

dental plaque accumulation.

Dental plaque

Dental plaque is a collection of microorganisms

found on a tooth surface as a biofilm, embedded in

a matrix of polymers of host and bacterial origin.1

It accumulates preferentially at stagnant areas such

as proximal surfaces between teeth, underneath

fixed dental prostheses and on the fitting surface of

removable dentures, as these sites are normally less

affected by the flushing effect of saliva and tongue

movement. Dental calculus is formed when the

minerals from saliva calcify the dental plaque. The

surface of dental calculus is rough and further attracts

plaque deposition.

Dental diseases

(a) Dental caries

Dental caries is a transmissible bacterial

disease process caused by acids from bacterial

metabolism diffusing into enamel and dentine

and dissolving the mineral.2 It is a major non-communicable

disease affecting the vast majority

of older adults. The estimated annual increments

of coronal3 and root4 caries are 0.86 and 0.5

surfaces respectively. A recent systematic review

highlighted that the trend of dental caries had

shifted from children to adults with the third peak

of caries emerging at around the age of 70, due

to the appearance of root caries.5 People who are

older, of lower socioeconomic status, tobacco users

and those with more severe gingival recession

and poorer oral hygiene have a higher risk of root

caries.6

Demineralisation of tooth substances occurs

when bacteria metabolise sugar in the mouth

to produce acid that demineralises the tooth

substances. This happens when food containing

carbohydrate is being consumed. This process

can be reversed by remineralisation of the

affected tissues naturally by salivary minerals

or therapeutically by fluoride. However, if

remineralisation does not happen due to persistently

low pH of the oral cavity e.g. frequent meals, or

unavailability of fluoride, the enamel breaks down

and cavities appear, and the infection can spread

to the underlying dentine. This causes sensitivity,

or sharp and mild to moderate degree of pain

when the patient consumes cold and sweet food

and beverage. The carious sites appear brown or

black with visible pits or cavities. Restoration

of the carious lesions is necessary to remove the

infected tooth substance, and to prevent plaque

accumulation and food stagnation to facilitate

proper toothbrushing.

When the infection spreads further to the

vascularised and innervated dental pulp, it causes

pulpal inflammation and necrosis. The severe

and spontaneous dental pain can keep the patient

awake. Dental abscesses may also develop. At

this stage, root canal treatment will be needed. It

is noteworthy that caries damages the tooth and

the restorative procedures can further weaken it,

risking its fracture upon receiving masticatory load.

Fluoride is an effective anti-caries agent which

halts demineralisation and promotes remineralisation

of enamel and dentine.7 Dentists usually apply

fluoride varnish, containing 22600 ppm fluoride,

2-4 times a year for caries prevention and arrest

of early lesions. In the past decade or two, silver

diamine fluoride (SDF) became the gold standard

for root caries prevention and treatment.8 It is also

effective in the remineralisation of deep carious

lesions on the occlusal surface and the treatment of

hypersensitive dentine. Among the professionally

applied topical fluorides, an annual application

of 38% SDF solution combined with oral health

education has been shown to be the most effective

way of dental root caries prevention.9

(b) Periodontal disease

Plaque-related gingivitis occurs when dental

plaque accumulates along the gingival margin over

days or weeks without disruption or removal while

non plaque-related gingival diseases can arise due

to various causes10-11 including genetic disorders

such as hereditary gingival fibromatosis, specific

infections, e.g. candidiasis, autoimmune diseases

of the skin and mucous membrane, such as lichen

planus, herpes simplex I & II, and leukaemia. The

initial phase of plaque-related periodontal disease

is gingivitis which involves host-immune response

to dental plaque. Healthy gingiva appears pink

and firm, and attaches closely to teeth, whilst it

reddens, swells, sores and bleeds on probing in

gingivitis (Figure. 1).

Figure 1:

This patient suffers from periodontal disease.

Heavy plaque deposition around the gingival

margin, bleeding on probing and recession of

the gingiva exposing the root surfaces can be

seen.

Figure 2:

Dental caries attack the lingual surface of the

lower anterior teeth of a Sjögren’s syndrome

sufferer. These sites are usually protected by

a continuous flow of saliva.

Certain drugs and smoking habits can modify

the host response to dental plaque. For example,

patients taking calcium channel blockers, antiepileptics

and immunosuppressants may show

abnormal gingival enlargement.12 Smokers usually

exhibit less gingival bleeding, greater alveolar bone

loss and clinical attachment loss. The treatment

response is suboptimal and healing is impaired.13 This

implies that periodontal diseases are more difficult

to detect and the treatments are less effective.

Plaque-related gingivitis can be resolved when

dental plaque is removed. However, if it is allowed

to accumulate for a long time, apical movement of

the gingival margin will lead to gingival recession

and hence root surface exposure. The root surface

dentine is prone to caries. The tooth may become

hypersensitive and present with pain or discomfort

to cold and other stimuli such as sour food.

The advanced stage of periodontal disease,

or periodontitis, is irreversible. The clinical signs

include increased probing depth, clinical attachment

loss, and tooth mobility and displacement.

Periodontal abscess with pus draining may be

present. In severe cases, the tooth may self-exfoliate.

The patient often complains of halitosis,

tooth mobility, poor masticatory efficiency,

chewing discomfort, and food packing.

Oral hygiene practice

The key prognostic factor of periodontal disease

is dental plaque accumulation. Therefore, good oral

hygiene practice that includes toothbrushing twice

daily and interdental cleaning are necessary. Non-surgical

periodontal therapy including scaling and root

planning aims to remove dental calculus and smoothen

the root surfaces to enable the resolution of gingivitis.

As an adjunct measure, 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate

mouthwash may be prescribed.14 However, its long-term

use is not recommended due to side effects like

a change in taste, staining of the teeth, the gingiva

and the dental appliances, irritation and superficial

desquamation of the oral mucosa. Oral antibiotics may

sometimes be necessary to eliminate causative bacteria.

For periodontitis, surgical periodontal treatment

involves flap surgery to expose root surfaces for

scaling and root planing. For cases with severe gingival

recession and bone resorption, grafting of soft tissues

or bone and guided bone regeneration to cover exposed

roots for aesthetics and to enhance bony support may

also be performed.

Dental plaque is a causative factor in both dental

caries and periodontal diseases. Proper oral hygiene

measures cannot be overemphasised. Mechanical plaque

removal by toothbrushing with regular fluoridated

toothpaste (1000-1450 ppm fluoride) twice daily is

mandatory. In high caries-risk cases, dentists may

recommend using high-fluoride (5000 ppm fluoride)

toothpaste. Interdental cleaning can be carried out with

the use of dental floss or an interdental brush.

Assisted toothbrushing is required for patients who

have problems with self-care. For those whose manual

dexterity has deteriorated, a modified toothbrush to

improve handgrip or the use of an electric toothbrush

may be helpful.

The inter-related medical and dental conditions

Medical and dental conditions are often interrelated.

Some chronic systemic diseases commonly seen in older

adults can directly affect the oral tissues. Medications

that modify the immune / inflammatory response or

reduce salivary flow can complicate oral health problems.

Dry mouth and reduced salivary flow

Saliva exerts an important protective effect on

the oral cavity through its flow and composition. Its

mineralising, buffering and antimicrobial properties

are crucial for preventing dental caries and providing

resistance to dental infections. Degenerative changes

of the salivary glands, diseases such as diabetes

mellitus and Sjögren’s syndrome15, head and neck

radiotherapy16, and an array of medications17 including

the antidepressants and some diuretics, can reduce

saliva secretion. Compositional change of the saliva to

low bicarbonate and phosphate concentration impairs its

buffering capacity. A longer time is needed to neutralise

the oral acid, hence inducing a higher caries risk.18

Although xerostomia, a condition when there is

a sensation of oral dryness resulting from diminished

saliva production, seldom presents as the main concern

for patients seeking medical or dental care. it can affect

up to one-third of older adults worldwide.19 Complaints

of xerostomia may be subtle and indirect: for example,

choking when dry food is taken, dry cough, the tongue

sticking to removable dentures. These problems can

be avoided by not taking dry food or by having a sip

of liquid when taking dry food. Since xerostomia is

a subjective feeling, its presence can often be missed

without asking the question, “do you feel your mouth is

dry?”.20

Clinically, saliva with decreased salivary flow is

viscous, sticky, frothy and bubbly. Those patients often

present with heavier dental plaque deposition, greater

number of dental caries and the lesions are located at

sites generally not susceptible to decay such as the

lower lingual region (Figure. 2), and more missing

teeth, worse periodontal condition and heavily restored

dentition, when compared to those with normal salivary

flow rate. Their oral mucosa looks dry and friable and

the tongue may appear dry and lobulated. They are

also more prone to oral mucosal infections such as oral

candidiasis. They may also experience difficulties in

speaking, swallowing, taste alteration and have burning

mouth syndrome. Their oral health-related quality of

life is also reduced.

Dentists usually detect oral dryness by testing if the

oral mucosa sticks to the dental mirror. Commercially

available test kit can be used to check the unstimulated

and stimulated salivary flow rates, and the pH and

buffer capacity.

Some patients may develop a habit of consuming

acidic food and drinks to stimulate salivary flow. This

habit should be deterred because it can lead to tooth

erosion. Tooth surface loss does not only jeopardise the

aesthetics when the anterior teeth become shortened, it can

also cause hypersensitivity or pain which may, depending

on its severity, require root canal treatment. Restoration

of the teeth can be complicated because of reduced

clinical crown height and lack of interocclusal space.

Medical physicians can consider prescribing

medications which are less xerogenic. However, if such

alternative medicines are unavailable, it is useful to

advise the patients to take the causative medications

during the day when activities in the oral cavity are at

the maximum, and avoid taking them before sleep when

the salivary flow rate is low, and also the number of

bacteria in saliva increases rapidly at night.21

Various palliative and preventive measures,

including pharmacologic treatment with salivary

stimulants, saliva substitutes, and the use of sugar-free

chewing gum/lozenges may alleviate some symptoms of

dry mouth and may improve the patient’s quality of life.

Diabetes mellitus patients

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a common endocrine

disorder in older adults. DM is linked to many different

dental problems and conditions such as periodontal

disease, delayed wound healing, taste alteration and

dental infections. The relationship between DM and

periodontal disease is bi-directional.22 Diabetic patients

have a higher risk of periodontitis, and their periodontal

conditions worsen control of diabetes treatments, while

people with periodontitis have an elevated risk for

dysglycaemia and insulin resistance. There is a high

association/risk between poor periodontal conditions

and diabetes complications.23

In addition, hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinemia

and dyslipidaemia cause increased oxidative stress,

inflammation, increased sympathetic activity, and

impaired insulin signalling in the salivary glands,

resulting in salivary gland dysfunction and the flow of

saliva is reduced.24 Diabetic patients often complain of

xerostomia. Reduced salivary flow also promotes dental

plaque accumulation and therefore further worsens their

periodontal health, making them more prone to dental

caries and oral mucosa infection.25 DM patients who use

removable dentures are more susceptible to traumatic

ulcers of the oral mucosa at the denture-bearing area

than non-DM denture wearers, probably due to slower

healing or delayed wound repair.

The current consensus guidelines advocat e

improving early diagnosis, prevention and co-management

of diabetes and periodontitis.23 DM patients

are advised to maintain good oral hygiene not only

for preventing periodontal disease but also for better

glycaemic control. Regular dental visits for denture

maintenance to avoid denture trauma are necessary.

Stroke, dementia and muscular disease

Sufferers of these conditions often have deterioration

in self-care ability. They require assistance to carry out

basic daily living activities. People with dementia usually

present with poor oral hygiene, heavy dental plaque

deposition, gingival bleeding, periodontal pockets, mucosal

lesions and reduced salivary flow.26 For stroke survivors,

apart from increased dental plaque accumulation, poorer

periodontal health and infection of the oral mucosa, they

also show impairment in mastication and swallowing

which restricts their food intake.27 Sarcopenia patients

with low muscle strength combined with poor manual

dexterity may find it challenging to grip the clasps of

a removable denture for its retrieval. In addition, their

neuromuscular control for stabilising a complete denture,

especially on the lower arch, may be compromised.

They require a longer training time to cope with new

dentures. Likewise, tooth loss is common in older

adults with sarcopenia. Compounded by the loss of

strength of the masticatory muscles, many sarcopenic

individuals experience problems with mastication.

Masticatory function and diet

Masticatory function is an important factor

influencing the quality of life in older adults.28 A

recent systematic review pointed out that masticatory

performance is significantly reduced in older adults with

sarcopenia, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary

diseases, and functional dyspepsia.29

The diet of people with deteriorated masticatory

function is typically soft, low in fibre content, and high in

carbohydrates and fat.30 This type of diet poses a high risk

for many chronic diseases including atherosclerosis and

cancer.31 Moreover, deterioration in masticatory muscle

strength and salivary flow may result when jaw activity

is reduced. High carbohydrate content of meals and

increased meal frequency result in a prolonged and ample

substrate supply for cariogenic and caries-producing

bacteria, hence, increasing the risk of dental caries.

Tooth-loss and teeth replacement

Tooth-loss is the endpoint of dental disease, as a

result of the severe and cumulative destruction of the

tooth or its supporting structures. After tooth extraction,

teeth adjacent to the extraction site may drift towards

each other and the opposing tooth may over-erupt. Loss

of teeth can adversely affect aesthetics, speech, and

chewing function.

Edentulism (or total teeth loss) also affects

oral food intake, and in the long run, can lead to

malnutrition. Moreover, tooth loss has a negative impact

on social life, self-esteem and oral-health related quality

of life.32 Older adults with multiple missing teeth also

have a higher risk of dementia than those with more

teeth.33 Unwanted tooth movement also affects oral

intake, and in the long run, can lead to malnutrition.

Replacement of missing teeth

Not all missing teeth needs to be replaced. For

example, dentists seldom replace the missing third molars

and, in some cases, even the second molars are not

replaced. Nonetheless, missing teeth need to be replaced

for restoring aesthetics and function, and maintaining

arch integrity to prevent unwanted tooth movement

due to the loss of neighbouring or opposing teeth.

Dental prostheses are commonly used for tooth

replacement. In Hong Kong, about two-thirds of the

older population wear some type of dental prostheses.34

Dental prostheses can either be fixed or removable

and are supported by natural teeth, mucosa or dental

implants. Dental prostheses are considered a plaque

retentive factor since the artificial material attracts

plaque accumulation and there are many stagnant areas

underneath the prosthesis where dental plaque and food

debris can accumulate. Additional effort has to be paid

to maintain cleanliness of the prostheses in addition to

the daily oral hygiene procedures of the natural teeth.

Dental implants expand the treatment modality

for tooth replacement and have become popular in the

past decade or two. Success of dental implant therapy

relies on careful patient selection which takes into

account their medical and dental conditions, as well

as compliance with oral hygiene measures. Diabetic

patients showed more marginal bone loss than non-diabetic

patients, albeit no significant difference in the

rate of implant failure.35

For diabetes mellitus patients, their condition

has to be well controlled before considering implant

therapy. BRONJ (Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis

of the jaw), after implant surgery and other oral and

maxillofacial surgeries have been reported in patients

receiving bisphosphonate treatment. Poor oral hygiene

is one of the risk factors. If this occurs, the oral

surgeon needs to remove the implant and resect the

necrotic bone.36 To prevent BRONJ, discontinuation of

bisphosphonate may be necessary before implant surgery

and maintenance of good oral hygiene is required.

In busy primary care clinics

In a busy primary care clinic, the primary care

physician may ask if the patient has any discomfort

with the teeth and oral tissues, and take a general

examination of the oral cleanliness by observing the

extent of dental plaque deposition on an annual basis.

Advise the patients to see a general dental practitioner

for a comprehensive dental examination if the oral

hygiene is sub-optimal or if they have any oral and

dental discomfort. It is recommended that patients with

medical disease should visit a dentist at least half-yearly

for check-ups and preventive care which include

scale and polish, fluoride application and adjustment of

dental prostheses if needed.

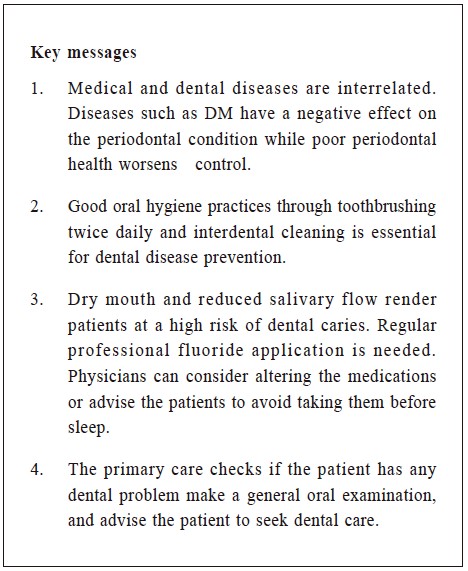

Conclusion

Older adults are often simultaneously affected by

medical and dental diseases. These diseases are interrelated.

It is prudent for physicians to be aware of

the common dental diseases and how they affect the

progress of medical diseases. Likewise, dentists should

also be cognizant of the patients’ medical conditions so

as to provide timely and appropriate treatment for them.

Dental and medical professionals need to collaborate

to provide suitable and well-planned treatment for the

benefit of our patients.

References

-

Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries Res. 2004;38(3):204-211.

-

Featherstone JD. Dental caries: a dynamic disease process. Australian dental

journal. 2008;53(3):286-291.

-

Griffin SO, Griffin PM, Swann JL, et al. New coronal caries in older adults:

implications for prevention. J Dent Res. 2005;84(8):715-720.

-

Hariyani N, Setyowati D, Spencer AJ, et al. Root caries incidence and

increment in the population - A systematic review, meta-analysis and metaregression

of longitudinal studies. J Dent. 2018;77:1-7.

-

Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of untreated caries:

a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94(5):650-658.

-

Zhang J, Leung KCM, Sardana D, et al. Risk predictors of dental root caries:

A systematic review. Journal of dentistry. 2019;89:103166.

-

Chu CH, Mei ML, Lo EC. Use of fluorides in dental caries management.

Gen Dent. 2010;58(1):37-43; quiz 4-5, 79-80.

-

Hendre AD, Taylor GW, Chavez EM, et al. A systematic review of

silver diamine fluoride: Effectiveness and application in older adults.

Gerodontology. 2017;34(4):411-419.

-

Zhang J, Sardana D, Li KY, et al. Topical Fluoride to Prevent Root Caries:

Systematic Review with Network Meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2020;99(5):506-513.

-

Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and

gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium:

Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the

Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J

Clin Periodontol. 2018;45 Suppl 20:S68-S77.

-

Hanisch M, Hoffmann T, Bohner L, et al. Rare Diseases with Periodontal

Manifestations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(5).

-

Kinane DF, Marshall GJ. Periodontal manifestations of systemic disease.

Australian dental journal. 2001;46(1):2-12.

-

Rivera-Hidalgo F. Smoking and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000.

2003;32:50-58.

-

Van Strydonck DA, Slot DE, Van der Velden U, et al. Effect of a chlorhexidine

mouthrinse on plaque, gingival inflammation and staining in gingivitis

patients: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(11):1042-1055.

-

Leung KCM, McMillan AS, Leung WK, et al. Oral health condition and

saliva flow in southern Chinese with Sjogren's syndrome. International

dental journal. 2004;54(3):159-165.

-

Pow EH, McMillan AS, Leung WK, et al. Salivary gland function and

xerostomia in southern Chinese following radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal

carcinoma. Clinical oral investigations. 2003;7(4):230-234.

-

Wolff A, Joshi RK, Ekstrom J, et al. A Guide to Medications Inducing

Salivary Gland Dysfunction, Xerostomia, and Subjective Sialorrhea: A

Systematic Review Sponsored by the World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI.

Drugs R D. 2017;17(1):1-28.

-

Bardow A, Moe D, Nyvad B, et al. The buffer capacity and buffer systems

of human whole saliva measured without loss of CO2. Arch Oral Biol.

2000;45(1):1-12.

-

Pina GMS, Mota Carvalho R, Silva BSF, et al. Prevalence of hyposalivation

in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerodontology.

2020;37(4):317-331.

-

Thomson WM. Dry mouth and older people. Australian dental journal.

2015;60 Suppl 1:54-63.

-

Sotozono M, Kuriki N, Asahi Y, et al. Impact of sleep on the microbiome of

oral biofilms. PloS one. 2021;16(12):e0259850.

-

Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, Jepsen S, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes:

a two-way relationship. Diabetologia. 2012;55(1):21-31.

-

Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, et al. Scientific evidence on the

links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and

guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes

by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of

Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(2):138-149.

-

Ittichaicharoen J, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. Is salivary gland

function altered in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and obesity-insulin

resistance? Arch Oral Biol. 2016;64:61-71.

-

Dorocka-Bobkowska B, Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz D, Wierusz-Wysocka B,

et al. Candida-associated denture stomatitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;90(1):81-86.

-

Delwel S, Binnekade TT, Perez R, et al. Oral hygiene and oral health in

older people with dementia: a comprehensive review with focus on oral soft

tissues. Clinical oral investigations. 2018;22(1):93-108.

-

Kwok C, McIntyre A, Janzen S, et al. Oral care post stroke: a scoping

review. J Oral Rehabil. 2015;42(1):65-74.

-

Ikebe K, Hazeyama T, Morii K, et al. Impact of masticatory performance

on oral health-related quality of life for elderly Japanese. Int J Prosthodont.

2007;20(5):478-485.

-

Fan Y, Shu X, Leung KCM, et al. Associations of general health conditions

with masticatory performance and maximum bite force in older adults:

A systematic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of dentistry.

2022;123:104186.

-

Wakai K, Naito M, Naito T, et al. Tooth loss and intakes of nutrients and

foods: a nationwide survey of Japanese dentists. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol. 2010;38(1):43-9.

-

Walls AW, Steele JG, Sheiham A, et al. Oral health and nutrition in older

people. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60(4):304-30.

-

Nordenram G, Davidson T, Gynther G, et al. Qualitative studies of patients'

perceptions of loss of teeth, the edentulous state and prosthetic rehabilitation: a

systematic review with meta-synthesis. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71(3-4):937-951.

-

Fang WL, Jiang MJ, Gu BB, et al. Tooth loss as a risk factor for dementia:

systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 observational studies. BMC

Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):345.

-

Department of Health. Oral Health Survey 2011. Hong Kong: Government

Printer, 2013.

-

Moraschini V, Barboza ES, Peixoto GA. The impact of diabetes on dental

implant failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal

of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2016;45(10):1237-1245.

-

Rupel K, Ottaviani G, Gobbo M, et al. A systematic review of therapeutical

approaches in bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ).

Oral Oncol. 2014;50(11):1049-1057.

Katherine CM Leung,

BDS, MDS (with distinction), PhD (HK), FHKAM (Dental Surgery)

Clinical Associate Professor;

Associate Dean (Taught Postgraduate Education);

Clinical Manager of the IAD-MSC.

Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong

Correspondence to:Dr. Katherine CM Leung, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of

Hong Kong, Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail:kcmleung@hku.hk

|