|

June 2015, Volume 37, No. 2

|

Original Article

|

|

Are we choosing the correct antibiotic to treat male urinary tract infection in primary care? - A cross-sectional studyKai-lim Chow 周啟廉, Pang-fai Chan 陳鵬飛, Loretta Kit-ping Lai 黎潔萍, David Vai-kiong Chao 周偉強 HK Pract 2015;37:51-57 Summary Objectives:

Design: A cross-sectional comparative study. Subjects: All male patients with acute lower urinary tract symptoms in three selected public primary care clinics in the Kowloon East Cluster of Hong Kong in 2013. Main outcome measures: Prevalence of organisms found in mid -stream urine specimens and their susceptibility to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate and to Nitrofurantoin. Results: The spectrum of organisms was wider in the primary care setting than that in the hospital. The prevalence of Escherichia coli was much lower than that found in the hospital. The overall susceptibility to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate was significantly higher than to Nitrofurantoin (p = 0.033) in public primary care clinics. Conclusion: Antibiogram from the hospital might not be a very accurate reference for primary care. Treating male patients with urinary tract infections empirically with Amoxicillin-Clavulanate may have a higher chance of bacteriological cure in the primary care setting. Keywords: Urinary tract infection, Male, Primary care, Amoxicillin-Clavulanate, Nitrofurantoin 摘要 目的:

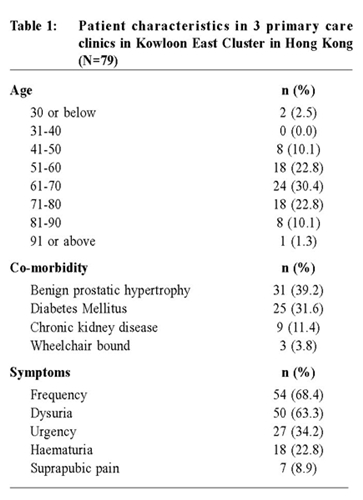

設計:橫切面比較性研究。 研究對象:於2013年,在本港九龍東聯網被挑選的三間公立基層診所內患急性下尿道病徵的男性病人。 主要測量內容:中段小便樣本含各樣細菌的流行率,及該等細菌對阿莫西林克拉維酸鉀片和呋喃妥因的受藥性。 結果:在基層醫療環境,小便中的細菌種類比在醫院的更多樣化,而大腸杆菌的流行率比在醫院中發現的則少許多。整體上,細菌對阿莫西林克拉維酸鉀片的受藥性比對呋喃妥因的顯著地高(p=0.033)。 結論:在醫院制訂的抗生素圖譜或許未能為基層醫療提供準確參考。在基層醫療,按經驗地以阿莫西林克拉維酸鉀片為患有尿道炎的男性病人治療,可能會有較高的細菌學上治癒機會。 關鍵字:尿道炎、男性、基層醫療、阿莫西林克拉維酸鉀片,呋喃妥因 Introduction Antibiotic resistance Urinary tract infection is one of the common clinical indications for an empirical antibiotic treatment (treatment based on clinical symptoms or signs unconfirmed by urine culture) in primary care. Treatment failure may be the result due to increasing antibiotic resistance, with local hospital data demonstrating 73%, 99% and 97% of Escherichia coli (E.coli), Klebsiella and Enterobactors specimens were resistant to Ampicillin respectively.1 Indeed, resistance to all classes of antibiotics has developed among other common and important nosocomial pathogens.2 Antibiotic resistance not only increases health costs but also adversely affects patient treatment outcome.3-4 Therefore treating patients with the right antibiotic is essential in reducing antibiotic resistance rate. Differences in disease epidemiology in different countries Urinary tract infections are usually treated with empirical antibiotics according to the data on the prevalence of the organisms causing the infections and their antibiotics susceptibility pattern, which varies between different countries even in primary care settings.5-8 This highlights the need for local prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility data for general practitioners who commonly treat urinary tract infections with empirical antibiotics in primary care.9 However, most existing local and overseas data were based on hospitalised patients, the majority of whom were female.6,10 Gender difference in disease epidemiology Urinary tract infection in male is much less common than that in female, and was considered as complicated urinary tract infection.11-12 However studies found that overall lifetime prevalence of urinary tract infection amongst men was estimated to be 13,689/100,000 and was rising with increasing age.13 Apart from the difference in prevalence of organisms, studies found that E.coli susceptibility to Ampicillin and to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate was less in specimens from male than that in female.14-16 Most management guidelines were developed from studies involving female patients.17-20 Management on urinary tract infection in men was currently underrepresented in medical literature and called for novel strategies in managing male urinary tract infection due to increasing antibiotic resistance.6,21,22 Problems in our locality There is currently no unified local primary care guideline on empirical antibiotic usage for patients with urinary tract infection. Previous studies showed variations in clinical approaches among physicians.23 Physicians in the primary care were also over-prescribing empirical antibiotics which increased the risk of antibiotic resistance.24 Since rates of resistance have undergone considerable variations, data on organisms prevalence and antibiotics sensitivity for different gender are needed and being updated constantly in order to determine the most appropriate empirical treatment for urinary tract infection.25 As there is a knowledge gap on the prevalence of the organisms in urine specimens and their antibiotic susceptibility in male patients in the primary care, this research aimed to describe the prevalence of organisms in urine specimens in male patients presented with lower urinary tract symptoms and to find out the common antibiotic susceptibility among different organisms. Hence we can obtain an updated local data as reference for choosing the best empirical antibiotic to treat male patients with urinary tract infection in primary care. There is no agreement at this time on what empirical antibiotic to treat male patients with urinary tract infection in the primary care setting. According to different studies, recommended first-line therapy usually included Nitrofurantoin, Quinolone, Trimethoprim and Amoxicillin-Clavulanate.8,26-29 The Health Protection Association and the Association of Medical Microbiologists recommended Trimethoprim and Nitrofurantoin as first-line empirical treatment for urinary tract infection in men because they are narrow-spectrum antibiotics that cover the most prevalent pathogens.30 In Hong Kong, it was found that the resistant rates of E.coli from all kinds of hospital specimens to Quinolone (37%) and Trimethoprim (46%) were high.31 For this reason, it was recommended that Nitrofurantoin or Amoxicillin-Clavulanate were the preferred choice of regimen in Hong Kong and in some other countries, too.1,32-33 However, there is no strong evidence on which one is better between Nitrofurantoin and Amoxicillin-Clavulanate in treating male patients with urinary tract infection and therefore this study will mainly focus on the susceptibility to Nitrofurantoin and to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate. Method Study design This is a cross-sectional comparative study using secondary data analysis. Subjects In the period from 1 Jan 2013 to 31 Dec 2013, all male patients aged 18 years old or older attending three selected regional public primary care clinics with any one of the classic acute lower urinary tract symptoms (i.e. dysuria, frequency of urination, suprapubic pain, urgency and haematuria) were identified by International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) code U71 and U07.34 The three public primary care clinics were under the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong and were located in the Sai Kung district, serving a population of over 300,000. Patients with known urinary tract structural abnormalities, had urinary tract instrumentation within one week of onset of symptoms, received oral antibiotic within the previous one week, other upper urinary tract symptoms (i.e. loin pain, flank tenderness, fever, rigors and other manifestations of systemic inflammatory response) or urine culture showing more than one organism identified in the urine sample indicating contamination were excluded. Laboratory test All eligible patients had saved their mid-stream urine specimen in a proper way taught by the clinic nurses with instructions such as retracting the foreskin before micturition and collecting the midstream portion of urine into the given sterile specimen bottle. The specimens were then sent to the microbiology laboratory. Significant bacteriuria in male is defined as the presence of a single organism with 103 or more colony forming units per 1 ml urine. 34 Data collection Patient data were collected from the computerised Clinical Management System, which is being used by all physicians working in Hong Kong’s public primary care clinics. Collected data included patients’ demographics, past medical history, symptoms on the day of consultation and the microbiology result of the urine cultures. Approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (Kowloon Central/ Kowloon East) of Hospital Authority. Statistical method Organism prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate and Nitrofurantoin were described. Comparisons on prevalence and susceptibility with the antibiogram in 2013 from a regional hospital of the same district were performed. 10 Pearson Chi-Square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to test the difference between categorical data. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All data analysis was performed using the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics version 21.0.0.0 for Windows. Results Study sample During the study period, 90 male patients were identified. Eleven were excluded based on our criteria (1 had recent urinary tract instrumentation, 4 with antibiotic administration within the prior 1 week, 4 with upper urinary tract symptoms, 2 had more than one organisms identified in the urine sample) leaving 79 cases eligible for the study. The age of patients Prevalence of organisms ranged from 27 to 95 with a mean of 65 years. Table 1 describes the demographics, co-morbidity and clinical symptoms of these patients.

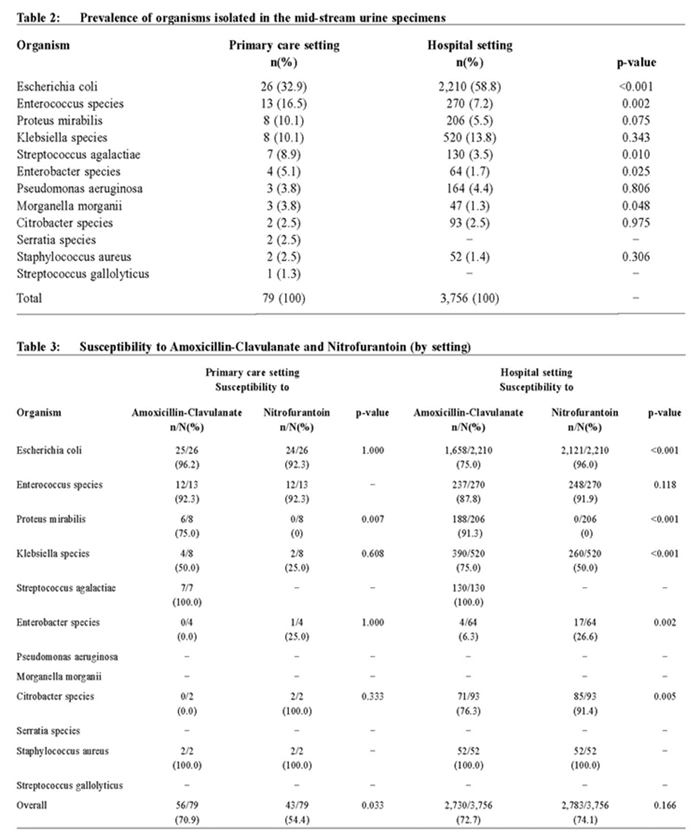

Prevalence of organisms E.coli, Enterococcus, Proteus and klebsiella accounted for about 70% of the organisms found. E.coli was the most prevalent (32.9%) among our patients but was significantly less prevalent than that in the hospital setting (32.9% vs 58.8%, p < 0.001) (Table 2). On the other hand, Enterococcus species were less prevalent in the hospital setting when compared to primary care setting (16.5% in primary care vs 7.2% in hospital, p = 0.002).

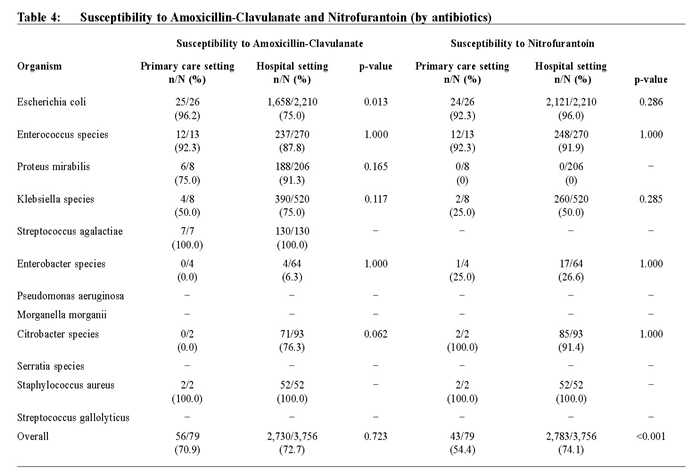

Antibiotics susceptibility Overall there was a significant difference in susceptibility to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate and to Nitrofurantoin (70.9% vs 54.4%, p = 0.033), which was not observed in the hospital setting (Table 3). No significant differences in susceptibilities were observed for E.coli and Enterococcus species within the primary care setting. However, similar to the hospital setting, Proteus isolates were mostly resistant to Nitrofurantoin. E.coli isolates in primary care were significantly more susceptible to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate than hospital isolates (96.2% vs 75.0%, p = 0.013) (Table 4). Overall susceptibility to Nitrofurantoin in the primary clinics was 20% less than that in the hospital setting (54.4% vs 74.1%, p < 0.001).

Discussion Our results demonstrated there was a lower prevalence of E.coli, but higher prevalence of other causative organisms including Enterococcus species in male urinary tract infection in the primary care setting compared with that in secondary care. This is comparable with previous community-based urinary tract infection studies which also demonstrated differences in antibiotic susceptibility between settings in primary and secondary care.35-37 This confirms the need for an antibiogram that is unique for primary care setting, especially for male patients. In our study, the overall susceptibility to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate was significantly higher than to Nitrofurantoin in the primary care setting, which was not observed in the hospital setting. This implies that if male patients with lower urinary tract infection are empirically treated with Amoxicillin-Clavulanate, more bacteriological cure can be achieved.

Clinical implication From this study, it was demonstrated that treating male patients presenting with acute lower urinary tract symptoms in the primary care setting in Hong Kong with Amoxicillin-Clavulanate had a better bacteriological cure rate than Nitrofurantoin. Early treatment with the more susceptible empirical antibiotic can avoid “delayed” treatment which causes more distress symptoms and even complications. Nevertheless, urine culture should be saved preferably before starting antibiotic to identify those organisms resistant to Amoxicillin-Clavulanate. Limitations This study was limited by its subject selection, where only three out of 73 public primary care clinics in Hong Kong were involved. However all samples from patients within that district attending the public primary care clinics were used. Further studies involving more centres should be considered in order to produce more generalisable results. Hospital data for individual patient characteristics and isolates were not available, and comparison could only be made through the hospital antibiogram. Sensitivity tests were only routinely performed for the two studied antibiotics, therefore susceptibility patterns for other antibiotics were unavailable. Collaboration with hospital microbiology departments should be considered in the future so that a more comprehensive analysis can be performed. Conclusion There is a need for a primary care -based antibiogram so that primary care physicians can provide the most appropriate treatment for suspected urinary tract infection and reduce antibiotic resistance. Our results suggest that treating male patients with urinary tract infection in our locality with empirical Amoxicillin-Clavulanate may have a better bacteriological cure rate. Ongoing surveillance and studies of urine culture results are required to assess the evolving resistance patterns of different causative organisms in urinary tract infections of male patients in the community.

Kai-lim Chow , MSc (Epidemiology and Biostatistics)

(CUHK), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FHKCFP, FRACGP

Resident Specialist Pang-fai Chan , MOM (CUHK), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FRACGP, FHKCFP Consultant Loretta Kit-ping Lai , MFM (Monash), FHKAM (Family Medicine), FRACGP, FHKCFP Associate Consultant David Vai-kiong Chao , MBChB (Liverpool), FRCGP, MFM(Monash), FHKAM (Family Medicine) Chief of Service and Consultant Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital and Tseung Kwan O Hospital, Kowloon East Cluster, Hospital Authority. Correspondence to : Dr Kai-lim Chow, Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care, United Christian Hospital, 130 Hip Wo Street, Kwun Tong, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China. References

|

||