Application of ambulatory blood pressure

monitoring in public primary care clinics in

Hong Kong: what do primary care doctors

need to know?

Kwai-sheung Wong 黃桂嫦,Ka-ming Ho 何家銘,Yim-chu Li 李艷珠,Catherine XR Chen 陳曉瑞

HK Pract 2022;44:81-89

Summary

Objective:

To delineate the indications for ordering

ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) in

public primary care setting and to explore patient

characteristics and results of the ABPM.

Design:

Cross-sectional descriptive study.

Subjects:

All patients who have had ABPM performed

from 1/12/2016 to 30/11/2017 in five General Outpatient

Clinics.

Main outcome measures:

The indications for

performing the ABPM, demographics of patients

undergoing ABPM and the results of ABPM were

studied.

Results:

There were 323 patients with ABPM done

within the study period with valid results. 64% were

female and 36% were male, and the average age was

64 ± 12 (19 to 94 years old). 67 (21%) with diabetes

mellitus and 53 (16%) with impaired glucose tolerance

or impaired fasting glucose.

For the indications for ABPM, 150 (46%) were

for establishing diagnosis of hypertension (HT) and

173 (54%) were for monitoring of blood pressure (BP)

control among hypertensive patients.

Among the diagnosis of HT group, 96 (64%) were

confirmed with the diagnosis of HT, 42 (28%) were

found to have white-coat HT only.

For the monitoring of BP control group among HT

patients, 98 (57%) were noted to have suboptimal BP

control and 67 (39%) were found to have white-coat effect.

Among the 65 patients whose ABPM had been

ordered although their clinic BPs being normal, 18 (28%)

were diagnosed to have masked HT and 19 (29%) were

diagnosed to have masked uncontrolled HT.

Conclusions:

ABPM greatly helped the diagnosis and

management of different types of HT in primary care.

Keywords:

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring,

hypertension, primary health care

摘要

目的 :

規劃在公共基層醫療環境中24小時動態血壓監測

(ABPM)的用途,並探索24小時動態血壓監測病人的特徵

和結果。

設計 :

橫斷面式描述性研究。

對象 :

從2016年12月1日至2017年11月30日期間,所有在

五個普通科門診診所進行了24小時動態血壓監察的病人。

主要結果測量 :

研究了進行廿四小時動態血壓監察

的原因、病人的人口統計學特徵及結果。

結果 :

在研究期間,有323位進行了廿四小時動態血

壓監察的病人的結果為有效。64%為女性,36%為男

性,平均年齡為64±12歲(19至94歲。67人(21%)患有

糖尿病,53人(16%)患上葡萄糖耐性障礙或空腹血糖

偏高。

至於進行二十四小時動態血壓監察的原因,150名

病人(46%)用於確定高血壓(HT)的診斷,173名病人

(54%)用於監測高血壓患者的血壓(BP)控制。

關於血壓高的的診斷中,96名病人(64%)被診斷為血

壓高,42(28%)被發現只有白袍高血壓。

關於血壓高病人的控制監察方面,98名病人(57%)的

血壓控制不理想,而67名病人(39%)被發現具有白袍

效應。

儘管診所血壓正常,但仍然進行二十四小時動態血

壓監察的65名患者中,18名(28%)被診斷出患有隱性

高血壓,19名(29%)被診斷出患有不受控制的隱性高血壓。

結論 :

廿四小時動態血壓監察有效地幫助了不同種類

高血壓的診斷和治療。

關鍵詞 :

廿四小時動態血壓監測、高血壓、基層醫療

Introduction

Hypertension (HT) is a common chronic disease

affecting more than 20% of adults globally1 and more

than 27% of Hong Kong (HK) people aged 15-84.2 It

is also one of the most common clinical conditions

encountered in primary care. Numerous studies have

shown that HT is one of the major cardiovascular risk

factors.3,4 For every 10 mmHg reduction in systolic

blood pressure (BP), the risk of major cardiovascular

disease events reduced significantly by 20%, leading

to a significant 13% reduction in all-cause mortality.5

Therefore, proper diagnosis and management of HT is

an important mission for primary care doctors.

Traditionally, HT is diagnosed based on office

or clinic BP readings. Recent studies have revealed

that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)

could provide better prognostic information about

cardiovascular disease than office BP measurement.6,7

As ABPM can provide multiple BP measurements

away from the medical environment, it gives a clearer

picture of the patient’s BP profile over a 24-hour period

including both awake and sleep time. Such valuable

information cannot be offered by office BP and home

BP measurements. This allows the identification

of individuals white-coat HT (WC HT), HT with

white-coat effect (HT with WC effect), masked HT and

masked uncontrolled HT. Therefore, some prestigious

international guidelines on management of HT have

recommended the use of ABPM in establishing the

diagnosis of HT or monitoring BP control in existing

hypertensive patients.8,9.10 Indeed, ABPM has been

shown to be cost-effective both in specialist services

and in primary care, with large amount of resources

being saved due to more rational drug prescribing

and better BP control.11 However, despite all of this

evidence, the application of ABPM in primary care is

still suboptimal. For example, a review of ABPM use

in 11 Asian regions including China, Japan, Korea and

Singapore published in the year 2019 noted that ABPM

was seldom available in primary care clinics.12 It is

therefore not surprising to find that ABPM has been

underused in the primary care setting.

ABPM services has been introduced to public

General Outpatient Clinics (GOPCs) of Kowloon Central

Cluster (KCC) under the Hospital Authority of Hong

Kong (HAHK) since 2015. It assists in the diagnosis of

HT in suspected hypertensive patients and monitoring of

BP control in hypertensive patients. Until this moment,

the service utilisation and the results of the ABPM

performed in local primary care clinics had not been

widely studied. To fill in this knowledge gap, this study

aims to delineate the indications for ordering ABPM in

the public primary care setting and to explore the patient

characteristics and the results of the ABPM. We believe

that the results of our study will provide important

background information for the use of ABPM in public

primary care clinics and enlighten family physicians on its

proper application and interpretation in HT management.

Methods

Study Design:

Cross-sectional descriptive study carried out at

public primary care clinics

Subjects:

All patients with ABPM done within the period

from 1/12/2016 to 30/11/2017 in five GOPCs of KCC

under the Hospital Authority of HK were included. It

was estimated that around 14000 hypertensive patients

attended these clinics in the period. ABPM would be

ordered in GOPC directly by the attending doctors if

indicated. Patients who were intolerant to ABPM or

whose ABPM data was invalid were excluded.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

ABPM measures blood pressure monitoring

patients’ BP during a 24-hour period. “ABPM awake”

and “ABPM sleep” were defined according to the

patients’ schedule. All patients who have undergone

ABPM were asked about the awake and sleep time

and these data were entered into an ABPM software

(cardioversions 1.16.6). They were advised not to do

vigorous exercise during ABPM. Awake BP readings

were measured in 30-minutes intervals. Sleep readings

were measured in 45-60-minutes intervals, depending

on the total number of sleeping hours, with a minimum

of 7 measurements during sleep. The minimum awake

measurements should not be less than 20. The ABPM

would be considered as invalid if the overall successful

measures were less than 70% of all readings.13

Indications for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

ABPM is usually indicated in the following

scenarios in our clinics based on the recommendations

from the NICE guidelines8:

-

To establish the diagnosis of HT, especially

if patients do not have out-of-office BP

measurements.

-

To monitor the BP control among

hypertensive patients, such as those with

unusual discrepancy between their clinic BP

measurement and home BP measurement,when

there are symptoms suggestive of hypotension,

or when evaluating drug resistant HT.

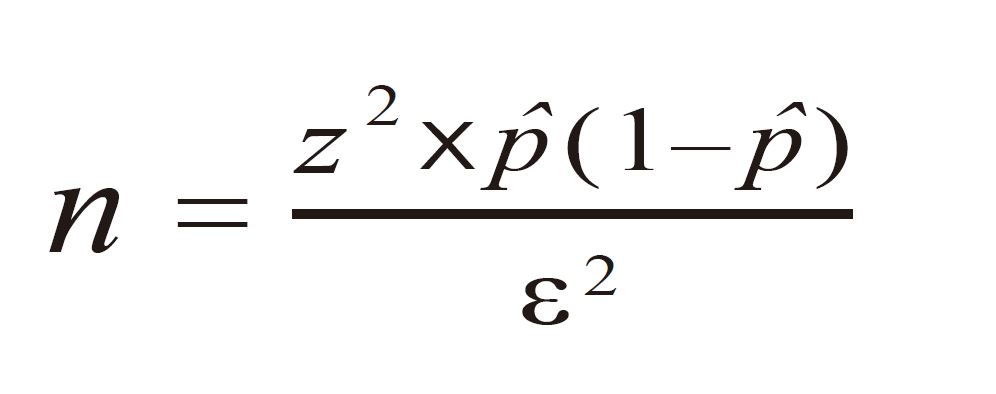

Sample size calculation

The prevalence of white-coat HT in the community

was reported to be 20 – 25% in the literature.14

Assuming the proportion of white-coat HT is 25% in

primary care clinics, margin of error being 5% and

confidence level of 95%, by using the formula:

(https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html; z is the z

score, ε is the margin of error and p̂ is the population proportion),

the required sample size is 289. To allow room for case

exclusion (~15%), 340 samples were included in the study.

Determination of variables

All relevant clinical data were retrieved from the

Clinical Management System (CMS) of HAHK. The

demographic data of the patients including age, gender

and comorbidities with diabetes (DM) or pre-diabetes

including impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose

tolerance were retrieved. The patients’ BP reading on

the date of ABPM ordered, the indications of the ABPM

and the final diagnosis after the ABPM was done were

also collected. According to the latest NICE guideline8

and American Diabetes Association guideline in

202015,cinic BP is defined as normal if the reading is

<140/90mmHg either in the presence or absence of DM.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Windows

version 26.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL], US). All

continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard

deviation. Categorical data are reported as number and

percentages. Chi-square test was used for comparing

the categorical variables. A P-value of less than 0.05 is

considered as statistically significant.

Results

349 patients had ABPM performed during the one-year

study period, among which 26 patients (7%) were

excluded from data analysis as their ABPM results

were invalid. Table 1 summarised the characteristics

of the remaining 323 patients (93%) included in the

data analysis. Among them, 208 (64%) were female

and 115 (36%) were male. They were aged 19 - 94

years old, with the mean age being 64 ± 12. Their mean

clinic systolic BP was 151 ± 18 mmHg and mean clinic

diastolic BP was 81 ± 12 mmHg. 65 patients (20%)

were found to have normal clinic BP readings at the

time when ABPM was ordered. Furthermore, 67 (21%)

were found to have concomitant DM and 53 (16%) with

pre-diabetes including impaired glucose tolerance or

impaired fasting glucose. The average waiting time for

the ABPM service was 26 days.

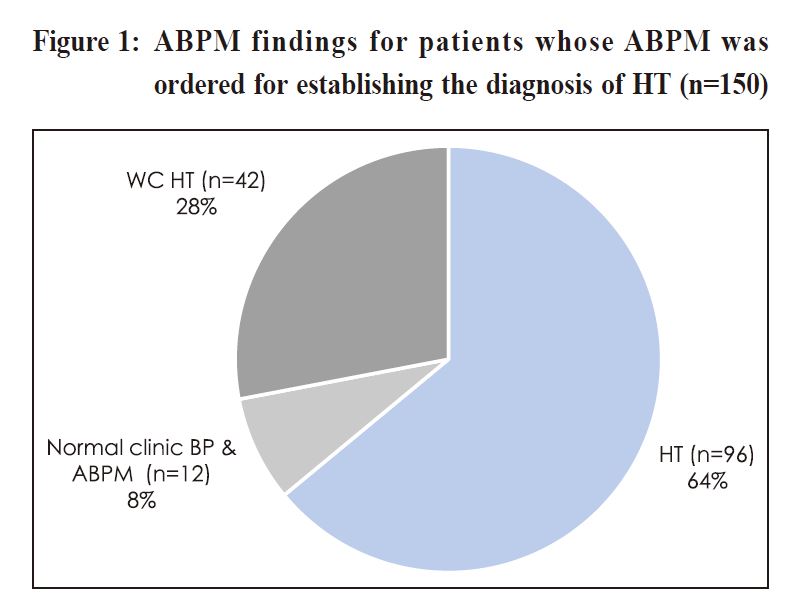

As to the indications for ABPM, 150 (46%) were

for establishing a diagnosis of HT and 173 (54%)

were for monitoring of BP control among confirmed

HT patients. For those whose ABPM were ordered for

diagnosing of HT, 96 (64%) were confirmed to have a

diagnosis of HT, 42 (28%) were found to have white-coat

HT, i.e. elevated clinic BP with normal ABPM

and 12 (8%) were found to be totally normotensive

( Figure 1). The age and gender distribution among the

subgroups were comparable ( Table 2).

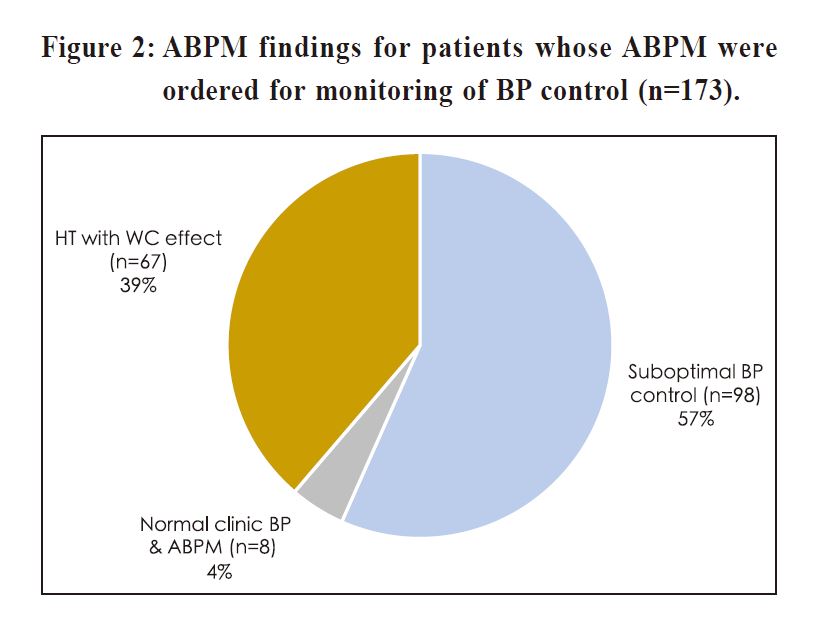

For those whose ABPM were indicated for

monitoring of BP control among hypertensive patients,

98 (57%) were noted to have suboptimal BP control

and 67 (39%) were hypertensive patients with white-coat

effect, i.e. elevated clinic BP but normal ABPM in

treated HT individuals (Figure 2). Again, the subgroup

analysis as shown in Table 3 revealed that their age and

gender condition were comparable.

Sixty-five patients had ABPM ordered although

their clinic BPs were normal (<140/90mmHg). Among

them, 37 (57%) were found to have elevated ABPM,

with 18 (28%) having masked HT and 19 (29%) having

masked uncontrolled HT ( Figure 3).

Discussion

Although wide evidence from literature has

confirmed the benefit of ABPM in establishing the

diagnosis of HT and the management of different types

of HT, its application in primary care is still far from

satisfactory. For example, a cross-sectional survey of

more than 400 primary care doctors in HK in 2019

found that there was a significant underutilisation of

ABPM, with only 1.6% doctors using this method to

diagnose HT and 4.1% using this for management of

HT.16 In our study, due to limited resource in the public

primary care system, only 349 cases had ABPM done

during the one-year study period and this figure was

definitely suboptimal in view of the large numbers

of HT patients management in the GOPCs. We hope

our study would help delineate the role of ABPM by

reviewing the application of ABPM in local primary

care clinics and therefore advocate its use among all

primary care doctors in HK.

Our study reveals that nearly one third of untreated

individuals were noted to have white-coat HT and

more than one third of hypertensive patients were

found to have white-coat effect. These findings are

consistent with a local study done in 2007 showing

that 28.2% of all HT patients had white-coat HT in

primary care.17 Similarly, in another local study done

by Chiang et al in 2013, 30% of treated hypertensive

patients in a public GOPC were found to have white-coat

effect.18 Currently, there is insufficient evidence

from randomised controlled trials to determine whether

white-coat HT warrants treatment.19 Dietary advice

and lifestyle modifications were recommended as the

mainstay of treatment for white-coat HT.20 With the

help of ABPM, over-diagnosis of HT could be avoided

in nearly 30% of cases and therefore prevent the wrong

labelling of “HT” among this group. Similarly, the use

of ABPM helps ease the worry of those HT patients

with W-C effect and subsequently avoid the unnecessary

medication augmentation. This is particularly important

as otherwise the patients will be at risk of hypotension

due to overtreatment and be susceptible to the potential

side-effects from drug treatment. All these findings have

corroborated the importance of doing ABPM before

establishing the diagnosis of HT or when white-coat

effect is suspected among treated HT patients.

Importantly, more than half of the patients were

found to have suboptimal BP control in the group of

hypertensive patients whose ABPM were ordered for

monitoring of BP control. This result is consistent with

findings from another study showing that more than

40% of patients labelled as having “HT with white-coat

effect” were actually having suboptimal BP control in

the local primary care clinics.21 This finding should alert

primary care doctors to the importance of conducting

ABPM for confirming the BP control status before

the clinical decision of “satisfactory control” is made

liberally. Although regular home BP monitoring (HBPM)

could help confirm the white-coat effect among

hypertensive patients too, self-reporting bias, patients

with impaired cognition and the lack of monitoring

during the sleep time by typical HBPM machine may

prompt the use of ABPM rather than HBPM.20 In view

of the fact that poorly controlled BP will significantly

increase hypertensive patient’s cardiovascular risks,

family physicians should carefully review their BP

control status during every follow-up visit and refer the

case to have ABPM if in doubt.

It is alarming to note that quite a number of

patients referred to ABPM with normal clinic BP were

found to have either masked HT (28%) or masked

uncontrolled HT (29%). A local study by CM Ng et

al involving type 2 diabetic patients who were not on

any antihypertensive in a tertiary clinic found that the

prevalence of masked HT was 18% by ABPM.22 The

high percentage of masked HT or masked uncontrolled

HT of our study might be explained by several reasons.

Firstly, when ABPM was referred for patients whose

clinic BP was normal, their home BP readings were

usually elevated. The discrepancy between the clinic

BP and home BP readings would prompt the attending

doctor to further assess their BP control by ABPM.

As the BP machines in the study clinics are under

regular maintenance and validation service provided

by the Hospital Authority, we assume the clinic BP

machines and measurements were accurate in our study.

Secondly, ABPM would be ordered for patients having

early development of cardiovascular complications or

chronic kidney disease (CKD) with seemingly well

controlled HT. This is a sensible choice as many such

patients were later confirmed to have masked HT

or masked uncontrolled HT by ABPM and therefore

warranting closer BP monitoring and stricter control.

Such people usually have more metabolic risk factors

and asymptomatic organ damage than those who are

truly normotensive.23 This is particularly important in

view of the large amount of evidence showing that

masked HT significantly increases the cardiovascular

morbidity.24,25 The long-term risk of developing

sustained HT, DM, or left ventricular hypertrophy in

masked hypertensive patient is 2 to 3 times greater than

that of individuals with normal in- and out-of-office

BP.26 With all these findings, we would like to appeal to

all primary care doctors to enhance the use of out-ofoffice

BP measurements including ABPM when there is

reasonable doubt on the BP control although the clinic

BP is normal. An accurate and timely assessment of

BP control could prevent or delay the development of

cardiovascular complications.

Limitations of the study

There are some limitations in this study. First, the

study was carried out in one single cluster of HAHK,

therefore these results from the public primary health

care sector might not be applicable to the private

sector or secondary care. In addition, only 323 cases

who fulfilled the ABPM referral criteria and with valid

ABPM results were included in the data analysis,

therefore selection bias might exist. Nevertheless, as

the data included all patients who had done ABPM

from five primary care clinics in HAHK during the

one-year study period, these data may give a realistic

representation of ABPM service performed in the

public primary care settings and had provided important

background information for future service enhancement.

Secondly, apart from DM and pre-diabetes, data on other

comorbidities such as ischemic heart disease, stroke or

CKD etc. had not been collected. It is therefore hard to

determine the correlations between the ABPM findings

with the cardiovascular or renal complications. Future

studies with more comprehensive data collection will be

needed to further explore this important aspect. Thirdly,

due to feasibility reasons, not all participants were able

to do the ABPM on the same day and their average

waiting time was 26 days. Patient’s clinic BP on the

date when ABPM was ordered might be substantially

different from the date when ABPM was performed.

Having said so, since most cases who attended the

GOPCs were comparatively stable cases and therefore

the four weeks’ time interval is a reasonable timeframe

where patients’ clinical condition would unlikely to

have dramatically changed. Lastly, because of the crosssectional

nature of the study, we were unable to adjust

for potential unmeasured confounders and therefore no

temporal or causal relationship could be established.

Conclusion

Our study successfully delineated the indications

for ordering ABPM in the public primary care setting,

explored the patient characteristics and the results of

the ABPM. ABPM was used for both establishing the

diagnosis of HT and monitoring of BP in hypertensive

patients. More than one third of primary care patients

undergoing ABPM were found to have either white-coat

HT or HT with white-coat effect. The use of ABPM

might help avoid unnecessary initiation or escalation of

antihypertensive drugs among these groups of patients.

In addition, more than half of treated HT patients

undergoing ABPM were found to have suboptimal

BP control, highlighting the important role of ABPM

in the monitoring of BP control among HT patients.

Furthermore, more than half of patients referred to

ABPM with normal clinic BP were found to have

masked HT or masked uncontrolled HT. Further study

is needed to explore the risk factors contributing to the

development of masked HT and to prevent or delay the

development of cardiovascular complications among

this group of patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all clinic staff of Department

of Family Medicine & GOPCs, KCC of the HAHK for

their professional service and unfailing support to this

service review on ABPM use, without which this project

would not have been accomplished.

References

-

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in blood pressure from

1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement

studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet. 2017; 389: 37–55.

-

Department of Health. Report on Population Health Survey 2014/15. 2017.

Department of Health. Hong Kong SAR.

-

GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national

comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and

occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a

systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet.

2017; 390: 1345–1422.

-

Eleni Rapsomaniki, Adam Timmis, Julie George, et al. Blood pressure and

incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years

lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet. 2014; 383:

1899–1911.

-

Dena Ettehad, Connor A Emdin, Amit Kiran, et al. Blood pressure lowering

for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016; 387: 957–967.

-

Yang W, Melgarejo JD, Thijs L, et al. Association of Office and Ambulatory

Blood Pressure with Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes. JAMA.

2019;322(5):409–420.

-

Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy

of blood pressure screening methods with consideration of rescreening

intervals: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(3):192-204.

-

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Hypertension in adults:

diagnosis and management, NICE Clin Guidel. 2019. Available from https://

www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/hypertension-in-adults-diagnosis-and-

management-pdf-66141722710213.

-

Nerenberg KA, Zarnke KB, Leung AA, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2018

guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of

hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:506–525.

-

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/

ACPM/AGS/ APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention,

detection, evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in adults: a

report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association

task force on clinical Pr. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–248.

-

O'Brien E. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement in

clinical practice and research: a critical review of a technique in need of

implementation. J Intern Med. 2011 May;269(5):478-495.

-

Shin, J, Kario, K, Chia, Y-C, et al. Current status of ambulatory blood

pressure monitoring in Asian countries: A report from the HOPE Asia

Network. J Clin Hypertens. 2020; 22: 384.

-

Parati G, Stergiou G, O'Brien E, et al. European society of hypertension

practice guidelines for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens.

2014; 32: 1359-1366.

-

Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LA, et al. Recommendations for blood

pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood

pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the

Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart

Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension 2005;

45:142–161.

-

Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care.

2020 Jan;43(Suppl 1): S1-S2.

-

Lee EKP, Choi RCM, Liu L, et al. Preference of blood pressure measurement

methods by primary care doctors in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional survey.

BMC Fam Pract. 2020; 21 (1):95.

-

Tam TKW, Ng KK, Lau CM. What are the predictors of white-coat hypertension

in Chinese adults? Hong Kong Practitioner 2007. Nov;29:411-418.

-

Chiang LK, Ng L. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) for

hypertension management in primary care setting: an experience sharing

from Kwong Wah Hospital. HK Pract 2013;35:5-11.

-

Nuredini G, Saunders A, Rajkumar C, et al. Current status of white

coat hypertension: where are we? Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2020 Jan-

Dec;14:1753944720931637.

-

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. Authors/Task Force Members:.

2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The

Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European

Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: The Task

Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society

of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018

Oct;36(10):1953-2041.

-

Chou SCW, Chau CKV, Yeung KK, et al. White coat effect can be an

illusion that may possibly result in sub-optimal blood pressure control? HK

Pract 2017;39:129-143.

-

Ng CM, Yiu SF, Choi KL, et al. Prevalence and significance of white-coat

hypertension and masked hypertension in type 2 diabetics. Hong Kong Med J.

2008;14(6):437-443.

-

Tientcheu D, Ayers C, Das SR, et al. Target Organ Complications and

Cardiovascular Events Associated With Masked Hypertension and White-

Coat Hypertension: Analysis From the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 2015 Nov 17;66(20):2159-2169.

-

Palla M, Saber H, Konda S, et al. Masked hypertension and cardiovascular

outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Blood

Press Control. 2018;11:11-24.

-

Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, de la Sierra A, et al. Relationship between clinic

and ambulatory blood-pressure measurements and mortality. N Engl J Med

2018;378:1509–1520.

-

Mancia G, Verdecchia P. Clinical value of ambulatory blood pressure:

evidence and limits. Circ Res. 2015 Mar 13;116(6):1034-1045.

Kwai-sheung Wong,

MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Associate Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinics, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority Hong Kong

Ka-ming Ho,

MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Associate Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinics, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority Hong Kong

Yim-chu Li,

MBBS, FHKCFP, FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Chief of Service, Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinics, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority Hong Kong

Catherine XR Chen,

PhD (Medicine), MRCP (UK), FRACGP, FHKAM (Family Medicine)

Consultant,

Department of Family Medicine and General Outpatient Clinics, Kowloon Central Cluster,

Hospital Authority Hong Kong

Correspondence to:

Dr Kwai-sheung Wong, Department of Family Medicine and

General Out-patient Clinic, Room 807, Block S, Queen Elizabeth

Hospital, 30 Gascoigne Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR.

E-mail: wks638@ha.org.hk

|